Chapter 14 Handling and transport

The principles of good handling

Horses are potentially dangerous because of their size, strength and speed. Using the responses that have evolved as part of their agonistic ethogram, they can kick, strike, bite and barge humans as readily as they do conspecifics. Additionally, they may deploy anti-predator strategies, such as charging, on humans.

Working with animals presents various dangers, so animal handling is a critical skill for veterinary students and veterinarians. In an Australian study of 2800 veterinarians, 51% reported a significant work-related injury during their career and 26% reported having an injury within the past year. In addition, large animal practitioners were most likely to have chronic or significant injuries.1 In a similar US study, 65% of veterinarians had sustained a major animal-related injury and 17% had been hospitalized within the previous year.2

In a survey of equine veterinarians in Australia, a list of frustrations with their work included unreasonable and disagreeable clients as well as those who provided inadequate facilities and/or could not control their horses. The risk of injury and the physical demands of equine veterinary work were also listed as distracting from the enjoyment of their career choice.3 From the moment they graduate, junior veterinarians not only have to take responsibility for their own safety but also that of the patient, their personnel and the client. This is a significant responsibility, especially when the patient requires sedation, anesthesia, euthanasia, suturing or is in behavioral extremis (e.g. upside-down in a horse trailer after a road-traffic accident). In addition, animals such as horses can be large, and with size comes greater power. Because horses are flight animals and therefore prone to hyper-reactive defensive behaviors, the danger to human handlers is exacerbated. So horses that are presented to vets can be fractious not only as a result of their disorder but they may also be largely unhandled or, worse, may have acquired dangerous responses to traditional handling techniques. Finally, there may be considerable variation in the safety of facilities, competence of handlers and the extent to which the horse is already primed with adrenaline secondary to trauma, pain or behavioral extremis.

Horses themselves are excellent barometers of handling skills in that they may struggle more and become generally distressed when poorly handled. Those that are handled correctly are easier to both examine and treat. Veterinarians who cannot handle animals are mostly unable to teach their clients how to do so, a state of affairs that clearly leads to an unfortunate spiral with the animal’s health and welfare ultimately suffering. However, handling the patient quietly and efficiently raises the image of the treating veterinarian in the eyes of those present.4

Thus, handling the patient is a fundamental additional aspect of the communication curriculum because building a relationship with the client through his or her animal, by acknowledging and relating to the animal, is a critical element in veterinary consultation models.5 Inappropriate handling can affect diagnostic parameters6 and even play a critical role in a compromised patient’s ability to cope.

Aggressive horses have usually learned that threats and attacks on humans are reinforcing because they effectively reduce the threat posed by the presence of humans. However, learning can be turned to our advantage since, for example, neonatal handling has a beneficial effect on the subsequent general tractability of foals.7

The prior experience and temperament of a horse are significant for prospective handlers whether they be riders, trainers, farriers or veterinarians. However, even without a full history or the benefit of an owner to advise them, experienced personnel can predict the most likely response by studying the body language of horses. Regardless of the presence or absence of alarm bells in a horse’s history and warning signs in its behavior, it pays to reduce risks when handling all horses, e.g. by ensuring that during all procedures, equipment and personnel within a stable are kept to a minimum and that personnel remain on the same side of the horse as one another (Fig. 14.1).

Tact and subtlety are the cardinal markers of good horsemanship. Young, naïve and fearful horses demand the greatest tact. Personnel should avoid making sudden movements so that one can clearly identify which responses can be elicited and controlled by a steady approach. Correct handling procedures can lower reactivity levels in horses, and may facilitate learning in some circumstances.8

Since horse handling is commonly based on negative reinforcement (see Ch. 4), it is worth remembering that for as long as force is used it will continue to be needed. It is fundamental therefore that the application of pressure must be followed by release (see Ch. 13). Under ideal conditions this means that just as the pressures applied during the most desirable forms of equitation are minimal, the very least force should be used to lead and control a horse when one is on the ground. It is incumbent on the horse handler to use a minimum of force because each episode of handling represents a learning opportunity. The horse that has learned to struggle and has been reinforced by being allowed to escape is more likely to offer the same behavior in future. Excessive force or the failure to release the pressure when the horse responds appropriately are likely to cause problems related to conflict and habituation.

It is always worth remembering how useful positive reinforcement can be in shaping desirable responses (Fig. 14.2), especially when aversive stimuli have been used previously. For example, horses that are reluctant to load into a trailer (float) can first be trained to approach a target and then the target can be moved to various locations inside the vehicle.9 The lessons learned this way rapidly generalize to novel conditions, such as different handlers and vehicles. A limited-hold procedure and the presence of a companion horse seem to facilitate training.

The use of the voice in horse handling has been both over-rated and under-rated. Horses respond to a handler’s body language and voice. When both are consistent in all handling sessions, the horse’s response becomes increasingly predictable as one would expect with any classically conditioned response. By using the same voice cues when training responses, a trainer can give a horse auditory cues that help to identify the required response (such cues become discriminative stimuli; see Ch. 4). If the human is conversing with the horse, there is the possibility that the horse may habituate to the noise and become reasonably calm if required to do little more than relax. However, the opportunities for associations between a verbal command and a certain response are diminished since the horse is challenged by the need to filter commands out of the conversation. In other words, discrimination becomes more difficult.

The color of clothes worn for handling horses is immaterial when compared with the stimuli horses associate with certain clothing.10 In the wake of reports that synthetic pheromones can modify behavior in other species,11 it is worth considering ways in which odors may be used to calm horses. Perhaps the role of familiar odors helps to explain why horse-lore makes mention of the pacifying effects of rubbing one’s hands on the chestnuts of a horse prior to ‘befriending’ it. On a more scientific basis, early reports of the effects of a synthetic ‘equine appeasing pheromone’ in reducing behavioral and cardiac indicators of fear during a fear-eliciting test (return to familiar conspecifics by parting a curtain)12 are exciting and suggest that horses may be effectively calmed before novel husbandry and training experiences. By the same token it may be that angry and frustrated humans emit characteristic odors in their sweat that signal to horses the emotional states of their handlers and thus increase the horses’ arousal.13 The effects of different handlers on the behavior of horses are sparsely reported, but it has been proposed that by looking for excessive ear movements when horses are led around an obstacle course, one can detect inexperienced handlers.14

Donkey handling

When faced with frustrating situations and forced to respond with aggression, donkeys tend to give fewer warning signs than horses. Additionally it should be borne in mind that because of their enhanced ability to balance, donkeys can easily cow-kick. Few donkeys have been taught not to lean when having their feet examined. This makes veterinary examinations of the hooves and farriery generally more difficult in donkeys than in horses and ponies. Despite their agility, restraining most donkeys is straightforward if their head can be controlled. Unlike some other species, such as pigs, all equids follow the general rule of ‘where the head goes, the body will follow’.

Approaching the horse

To avoid emerging from horses’ blind spots (see Ch. 2), personnel should always approach them from the side. Convention is that horses are approached from the left. The merit of this tradition may be substantiated by research showing that horses generally use the left eye to observe novel stimuli.15 However, this convention can be revisited in horses that are being trained to extinguish fearful responses associated with handlers. By avoiding staring at horses one may be able to reduce the chances of this being misinterpreted as a prelude to predation or the challenge of a conspecific. That said, there is some evidence from a study of well-handled horses that eye contact does not necessarily affect a horse’s latency to approach humans.16 The speed with which humans move can certainly influence equine responses, e.g. walking quickly past the point of balance at the animal’s shoulder in the direction opposite to desired movement is an easy way to induce an animal to move forward.17

Generally it is helpful to approach an unfamiliar horse slowly in a non-menacing stance, with the body relaxed and slouching slightly. If a penned horse is facing away from the stable door or yard gate, handlers should make noises to encourage it to face them. This prevents handlers from being kicked as they approach the horse and is even considered by some to be an important sign that the horse is showing ‘respect’. If horses ever regard humans as analogous to conspecifics, they could be excused for having problems reading our body language unless we are regarded as issuing constant (and often hollow) threats (because our ears are permanently pinned back).18 Regardless of this, it remains unclear why horses would need to show ‘respect’ to other horses, and therefore submission or subordinance are perhaps more appropriate terms for displays of social deference. That said, most riders want their horses (whether they are companion or performance animals) to be compliant first and foremost, so interpretations of rank may be entirely irrelevant.

Restraint

Once they have begun to exhibit a flight response, most horses that are restrained by the head will continue to struggle until the pressure around the head is released. Horses should be tied up with a secure halter (or headcollar) and rope and never by the reins or a lead attached to the bit. The rope should be tied to a length of bailing twine, which is attached to a solid object. Because it is more readily broken than regular lead ropes and reins, bailing twine is used in combination with quick-release knots in case a struggle ensues. Many serious injuries have been inflicted on both horses and handlers when horses have thrown themselves to the ground in a bid for freedom (Fig. 14.3) or when rails have broken or posts have come out of the ground, so it is important that the bailing twine is weaker than the fixed object to which the horse is tied. Nevertheless, some horse-trainers disagree with this advice since they claim that a breakable connection between the horse and the fixed object actively encourages horses to pull back. The extent of flight responses among horses that are tied up means that the act of releasing horses can be very dangerous, even if they are secured only by quick-release knots. The danger is magnified when more than one horse is tied up and a wave of socially facilitated hysteria crashes over them.

The various roping techniques developed by horsefolk who had no chemical agents with which to pacify horses during aversive interventions have been catalogued elsewhere.19–21 While one cannot deny the inventiveness of the horse handlers who developed these approaches, the necessity that bred it may have passed. While it may be convenient to keep a horse still and safe for a given procedure, the crudity of these forms of physical restraint should be questioned in the light of current thinking about analgesia in companion animals. There is no justification for allowing animals to undergo pain.22 Ethically, one could argue that psychological threats are as aversive as pain itself. By the same token, there is no justification for allowing horses to fight against physical restraint when there is no evidence that they can predict that the episode will ever end.

If, during a handling procedure, a horse is not likely to learn good associations with personnel, there is a very strong argument for avoiding it learning anything. In practice, while emergencies may necessitate using physical restraint before veterinary assistance arrives, chemical agents are indicated more often than force. It is inevitable that some veterinary interventions with horses will be painful, so some level of physical restraint is usually needed to control equine patients, even if it is only to allow administration of chemical restraint. Since horses show a peak in plasma beta-endorphin concentrations23 (and so are likely to be least sensitive to noxious stimuli) in the early morning, it has been suggested that this may be the preferred time to undertake elective aversive procedures.13

The natural inclination of horses to run from trouble makes them difficult to deal with in the open. Although attempts are sometimes made to hold horses in a corner of a field or yard for interventions, horses are usually much safer in a stable, especially one with enough bedding on the floor to prevent them slipping. Anything that may get in the way during a struggle or a forced retreat by the handler, most notably water buckets, should be removed from the stable before any invasive handling or veterinary procedure. Stables with low ceilings are sometime helpful when handling horses that are inclined to rear or have learned to throw their heads up to avoid a twitch. Ceilings suitable for this application have no projections (such as jutting beams) from them that might damage a horse’s head or neck. The presence of the ceiling prevents the horse from gaining momentum as it swings its head up. Though the horse might throw its head up once, it is likely that it feels the ceiling with its ears, and rarely bothers a second time. Rectal examinations may be safely carried out by working round the side of a door. Temporary stocks can be built by placing bales of straw around the horse’s hindquarters.

Equipment for restraint

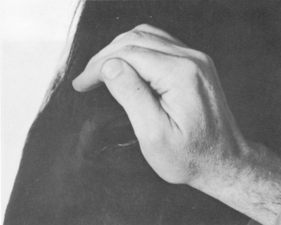

For most veterinary procedures all that is needed is a reliable attendant to hold the horse firmly with a halter and reinforce appropriate behavior by stroking the animal in anatomical areas associated with stress reduction, including the forehead, neck and withers. Cupping a hand over a horse’s eye on the side on which it is being treated is often very helpful, especially for needle-shy horses (Fig. 14.4). Tying horses up for aversive procedures is inadvisable since their tendency to fight against such restraint usually precipitates an attempt to flee and ultimately increases fear and the likelihood of damage to equipment or, worse still, injury to themselves or personnel.

Figure 14.4 A hand cupped over the eye of a horse can reduce fearful responses to veterinary personnel.

(Reproduced from Rose & Hodgson.21)

Physical restraint should not be used in ways that directly compromise horse welfare. When increased restraint is required, hobbles, a tail rope or service hobbles (see Fig. 12.5) may be used, but these should be seen as emergency measures rather than routine approaches. Horses may be controlled completely by being cast and tied with ropes, but this is rarely necessary since the same result can be achieved more readily by methods of general anesthesia. Occasionally it is suggested that a twitch or rope gag, often found useful when dealing with the hindquarters of a fearful horse, may work by distracting the animal. This is something of an understatement since, at least in the short term, the distraction is pain. However, the pain may be rapidly modified by endorphins.24

The twitch

A time-honored method of restraining horses is to apply a constriction to the upper lip as a so-called twitch (Fig. 14.5). It has the merits of being simple, effective and easy to apply, and is comparatively safe for the horse and the operator. For mildly painful, brief procedures, a twitch will give some added security. It certainly has a place in the protocol for nasogastric tubing of many horses since it seems to reduce their ability to flick the advancing tip out of the esophageal sphincter (Ken Sedgers, personal communication 2002). Twitches come in a variety of forms, from a simple loop of rope attached to a bull’s nose ring, through to a pair of metal pliers called the humane twitch (because it may be associated with less tissue damage in the hands of a novice than a homemade twitch). As with any means of applying pressure, the narrower the element that makes contact with the horse the greater the chances of pain and even permanent damage. Twitches with soft, thick rope and light (i.e. plastic) handles are generally safest. Snaring as much of the upper lip as possible when applying a twitch seems to increase its effectiveness and reduce the chances of it slipping. The constriction should be loosened every 15 minutes or so to maintain perfusion of tissues distal to it. Additionally this is sound practice since the effectiveness of the twitch tends to wane after this period in many cases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree