CHAPTER 5 Growth

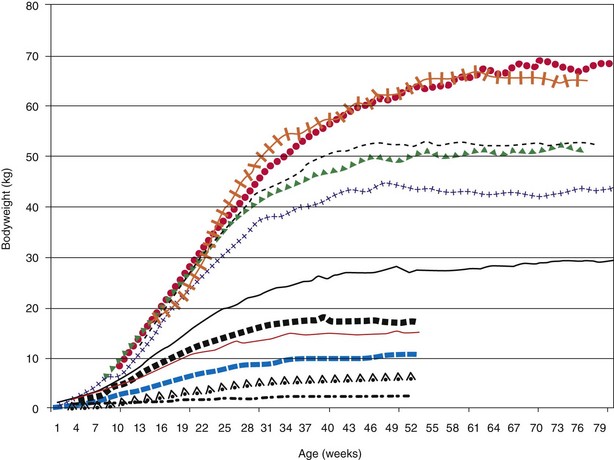

Generalizations about normal growth in puppies and kittens are difficult to make; this is particularly true in respect to dogs because of the wide variety of breeds encompassing many body shapes and sizes. Dogs are one of the few species with such a variety of size, which makes metabolic and growth rates significantly different. Normal adult dogs can vary in size from less than 5 lb to 150 lb in weight and still be healthy. This diverse morphologic range is rarely seen in any other species. Not only are there differences in the length of the exponential growth phase but also in the individual rates of growth (Figure 5-1).

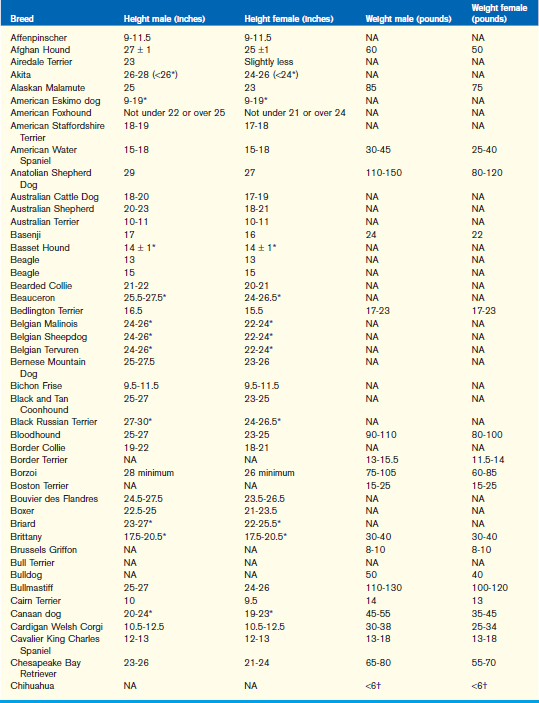

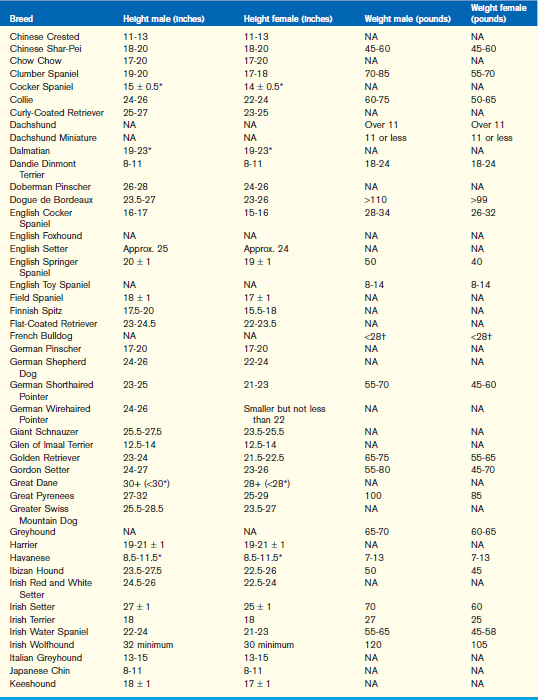

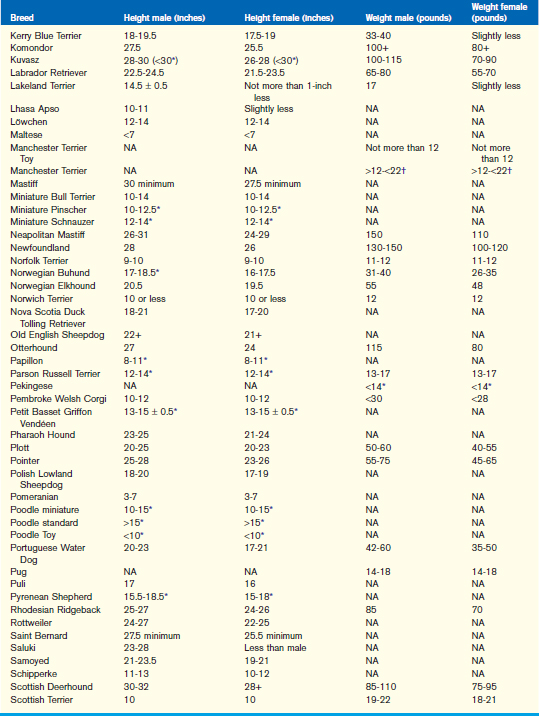

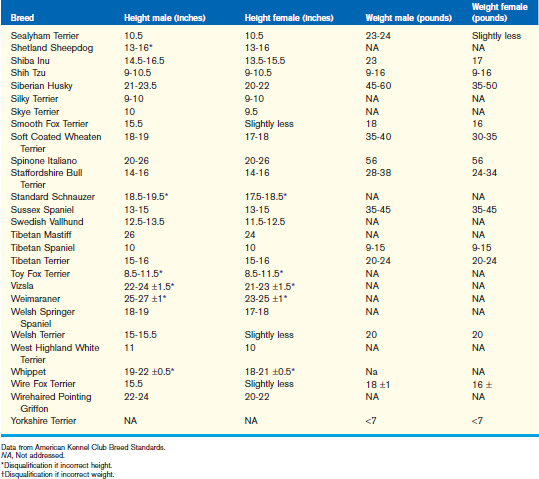

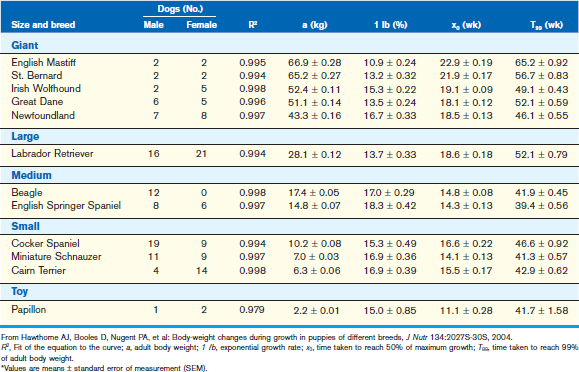

Determination of appropriate growth for an individual animal can be difficult. Unless a particular animal is still with siblings or has an owner with a good understanding of not only this breed but also of this specific lineage, normal growth for a particular animal can be difficult to define. An example of this situation is manifest in the Dachshund—a breed in which miniatures (less than 11 lb) and standards (16 to 32 lb) can be whelped in the same litter. Generalizations about normal growth can be made between dog breeds that will attain approximately the same adult size (Table 5-1).

TABLE 5-1 Growth characteristics of different dog breeds calculated by fitting a logistics equation to growth curves*

Assessment of normal stature in dogs can be difficult. Purebred breeds have written standards that include optimal size, usually height at the withers, but occasionally include weight guidelines (Table 5-2). Seasoned breeders usually have enough experience to recognize abnormal puppy growth trends. This does not mean all purebred dogs meet their standards requirement. Dogs with registration papers may or may not be “show” dogs; these “pet quality” dogs (graded as pet quality by the breeder because of a variety of faults, one of which may be size) are sold and should ideally be spayed or neutered. Unfortunately, the new pet owners may not sterilize their pets, and if the breed is particularly popular, may breed with another registered pet quality dog. Since these pet owners do not have the expertise in genetics or an understanding of the breed type, these puppies often have issues relative to their breed standards and frequently these dogs are much larger than the written standard requires. This is illustrated by the 100-lb registered Golden Retrievers (standard calls for 65- to 75-lb males) seen daily in the veterinary hospital.

Dogs that are bred, shown, and become champions have survived in the gene pool by meeting the rigors of independent judging in the show ring; by definition the dog show is designed to “exhibit” correct breeding stock. An example of this situation is the requirement for the Lakeland Terrier directed by its written parent club standard, which calls for the male to be  inches at the withers (

inches at the withers ( inch). Another example are the Miniature Dachshunds, which are not to exceed 11 lb. Some standards require disqualification if size requirements are breached, whereas in other breeds, deviation from the suggested size (either height or weight) is considered a significant fault in the show ring. The net effect is that purebred dog breeds do have standard sizes that a veterinarian can obtain, which is useful in determining if a particular puppy is incorrectly sized (see Table 5-2). However, it should be remembered that a puppy may be considerably sized incorrectly and still be healthy. Mongrel puppies have no known expected growth guidelines, unless the veterinarian can get some information on the parents’ size. It must also be kept in mind that pregnancies that occur without human supervision may have multiple sires, thereby confounding the issue.

inch). Another example are the Miniature Dachshunds, which are not to exceed 11 lb. Some standards require disqualification if size requirements are breached, whereas in other breeds, deviation from the suggested size (either height or weight) is considered a significant fault in the show ring. The net effect is that purebred dog breeds do have standard sizes that a veterinarian can obtain, which is useful in determining if a particular puppy is incorrectly sized (see Table 5-2). However, it should be remembered that a puppy may be considerably sized incorrectly and still be healthy. Mongrel puppies have no known expected growth guidelines, unless the veterinarian can get some information on the parents’ size. It must also be kept in mind that pregnancies that occur without human supervision may have multiple sires, thereby confounding the issue.

Domestic cats, on the other hand, with a few exceptions, such as the large Maine Coon cat, are generally fit into the same size range relative to height. There are some substantial differences in size of skeletal structure and weight. Examples would be comparing many of the heavy-boned, stout English breeds with the slender athletic Southeast Asian breeds. The Cat Fanciers of America recognizes 39 breeds, each with a written standard. Only one has actual recommendations for ideal weight; the remaining recommendations are either generalized as small, medium, or large or do not address size at all (Table 5-3).

TABLE 5-3 Size recommendations for cats

| Breed | Size (lb) |

|---|---|

| Abyssinian | NA |

| American Bobtail | NA |

| American Curl | M 7-10; F 5-8 |

| American Shorthair | NA |

| American Wirehair | NA |

| Balinese | Medium |

| Birman | Medium |

| Bombay | Medium |

| British Shorthair | Med to large |

| Burmese | Medium |

| Chartreux | NA |

| Colorpoint Shorthair | Medium |

| Cornish Rex | Small to med |

| Devon Rex | Medium |

| Egyptian Mau | Medium |

| European Burmese | Medium |

| Exotic | NA |

| Havana Brown | Medium |

| Japanese Bobtail | Medium |

| Javanese | Medium |

| Korat | NA |

| LaPerm | Medium |

| Maine Coon | Med to large |

| Manx | NA |

| Norwegian Forest Cat | Large |

| Ocicat | Med to large |

| Oriental | NA |

| Persian | NA |

| RagaMuffin | Large |

| Ragdoll | Med to large |

| Russian Blue | NA |

| Scottish Fold | Medium |

| Selkirk Rex | Med to large |

| Siamese | Medium |

| Siberian | Med to large |

| Singapura | Small to med |

| Somali | Med to large |

| Sphynx | Medium |

| Tonkinese | Medium |

| Turkish Angora | Medium |

| Turkish Van | NA |

NA, Not addressed

Data from The Cat Fanciers’ Association.

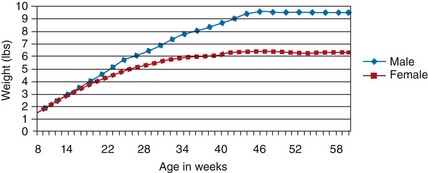

Kittens grow on average 100 gm/week up to 6 months of age. Average-sized kittens weigh roughly a pound per month of age up to 10 months. When reviewing the feline growth chart, male kittens are usually in the upper two-thirds, whereas females routinely fall into the lower two-thirds (Figure 5-2).

Figure 5-2 Mean growth curves for domestic cats. This graph is a relative growth time line for kittens.

(Data from Harlan Sprague Dawley, Inc., July 1, 1996, catalog.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

), St. Bernard (

), St. Bernard ( ), Irish Wolfhound (

), Irish Wolfhound ( ), Great Dane (

), Great Dane ( ), Newfoundland (

), Newfoundland ( ), Labrador Retriever (

), Labrador Retriever ( ), Beagle (▪), English Springer Spaniel (

), Beagle (▪), English Springer Spaniel ( ), Cocker Spaniel (

), Cocker Spaniel ( ), Miniature Schnauzer (

), Miniature Schnauzer ( ), and Papillon (

), and Papillon ( ).

).