CHAPTER 39 Genetic Screening of Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is the most common form of heart disease in cats.1 It is an adult-onset myocardial disease known to be inherited in the Maine Coon and Ragdoll breeds, and causative genetic mutations now have been identified in both of these breeds.2,3 A number of small families of cats with several affected members have been observed in a few additional breeds including the Norwegian Forest cat, British and American Shorthair, Sphynx, Siberian, and Bengal. This may suggest that hypertrophic cardiomyopathy also is an inherited disease in these breeds, although conclusive genetic studies have not been performed to date. Given the familial nature of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the Ragdoll and Maine Coon breeds, as well as the significant clinical consequences of the disease, cat breeders have expressed increased interest in genetic testing. Additionally, pet owners often are curious to know more about the underlying cause of their cat’s disease. Although this chapter will emphasize the current state of genetic testing for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Maine Coon and Ragdoll cats, a useful and frequently updated Web site for veterinarians and cat breeders interested in future developments in familial feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy as well as other feline inherited diseases is maintained by the Feline Advisory Board.4

ETIOLOGY

MAINE COON HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY

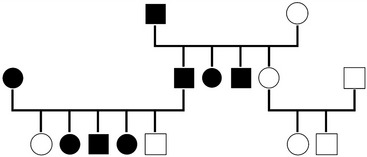

A familial form of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the Maine Coon cat was reported by Dr. Mark Kittleson at the University of California, Davis, in 1999.5 Breeding studies demonstrated that it was an autosomal dominant trait. Autosomal dominant traits should have the following criteria: males and females generally are affected equally, every affected individual should have at least one affected parent, and the trait generally is observed in every generation (Figure 39-1). Affected animals may carry the genetic mutation on one or both copies of the gene. If the mutation is on both copies of the gene (one inherited from each parent), they are called homozygous for the mutation and will pass one copy of the mutation to all of their offspring. They are defined as heterozygous if they have one gene with the mutation and one normal gene. Heterozygous cats have a 50 per cent chance of passing on the genetic mutation to their offspring. This does not mean that 50 per cent of a litter of kittens will have the mutation, but rather that each kitten has a 50 per cent chance of having the mutation. The litter may actually have from zero to 100 per cent of kittens born with the mutation.

In the Maine Coon cat a genetic mutation has been identified in the myosin binding protein C (MYBPC3) gene.2 Myosin binding protein C is a cardiac sarcomeric protein involved in cardiac contraction. It is the second most commonly mutated gene responsible for the human form of the disease.6 In the Maine Coon cat the mutation is a single base pair change from a guanine to a cytosine in the 31st codon of the gene. The mutation changes the highly conserved amino acid that is produced from alanine to proline, a large amino acid with a ring. Additionally, the alteration of the amino acid is predicted to change the structure of myosin binding protein C in this region, and alters the ability of the cardiac protein to interact with other contractile proteins.

Homozygous (two copies of the mutated gene) Maine Coon cats are thought to typically, but not always, develop a more severe form of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and may show clinical signs before 4 years of age.2 Heterozygous (one copy of the mutated gene) cats may develop the disease at a later age and have milder signs. As mentioned a small percentage of cats with the mutation may never show clinical signs of the disease, as a result of incomplete penetrance. Genetic modifiers that affect the expression and penetrance of the disease are likely, but have yet to be determined.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree