CHAPTER 3 Gastrointestinal and Peritoneal Infections

The common infectious diseases of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and their pathogenesis are covered in detail individually in other chapters of this text. The primary goals of this chapter are to identify the normal microflora throughout the GI tract and briefly discuss an approach to the diagnosis and management of the primary clinical syndromes associated with these infectious processes.

ORAL CAVITY

Normal Flora

Most information regarding the normal flora of bacteria in the equine pharynx relates to upper respiratory tract infection and lower respiratory tract infection attributed to aspiration. Comparatively few studies have examined the normal flora of the equine oral cavity. Several aerobic and facultatively anaerobic organisms have been isolated from various locations throughout the pharynx, most notably Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus.1,2 Anaerobic bacteria isolated from the normal equine pharyngeal tonsillar area include bacteria from the genera Bacteroides, Eubacterium, Fusobacterium, Clostridium, and Veillonella.3

Infectious Disorders

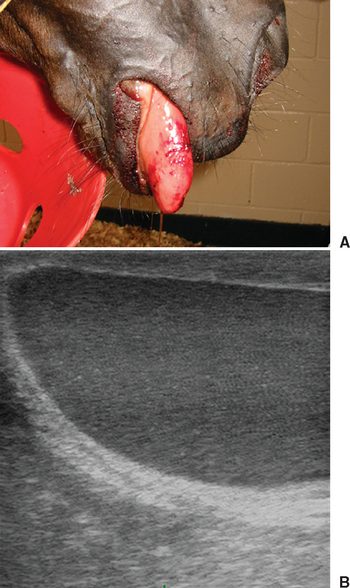

Unlike in small animals, infectious diseases of the oral cavity are relatively rare in horses. Primary problems with a possible infectious etiology include periodontitis and tooth root abscesses, pharyngitis, and dysphagia. Anaerobic organisms are frequently associated with tooth root abscesses.4 Other infectious problems with potential impact on the oral cavity include infection from Actinobacillus lignieresii, the organism associated with swollen or “wooden” tongue5,6 (Fig. 3-1); various fungal organisms such as Candida spp., which can cause thrush in foals (see Chapter 53); viral diseases such as vesicular stomatitis7 (see Chapter 24); and infectious causes of dysphagia such as Clostridium botulinum8,9 (botulism, see Chapter 46), equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (see Chapter 59), and West Nile virus (see Chapter 21).

ESOPHAGUS AND STOMACH

Normal Flora

The esophagus and stomach are not sterile environments. In one study, 2.8 × 109 total and 2 × 108 viable bacteria per gram of ingesta were recovered from the fundic region of normal ponies, with 1.9 × 109 total (but only 10 × 106 viable) bacteria/g recovered from the pyloric region.10 In both regions, gram-positive organisms (rods and cocci) predominated, and very few cellulolytic bacteria (100-300/g) were isolated,10 suggestive of the capacity for fermentation but minimal ability to utilize forage. Colonization of and attachment to the gastric squamous mucosa by several indigenous Lactobacillus spp. were recently described.11

Infectious Disorders

Infectious diseases of the esophagus mainly occur secondary to perforation and involve a mixed population of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. Although polymerase chain reaction (PCR) fragments unique to gastric-dwelling Helicobacter spp. have been identified in horses, an association between H. pylori and ulceration has not been established in adult horses or foals.12,13 One case of emphysematous gastritis from Clostridium perfringens has been reported.14

SMALL INTESTINE

Normal Flora

Few studies have evaluated normal microbial populations in the equine small intestine. Total bacterial counts and proportion of gram-positive bacteria recovered from the ileum were similar to those seen in the stomach,10 but viable bacteria numbered 3.6 × 107. In a study analyzing only anaerobic bacteria, increasing numbers of both culturable and proteolytic bacteria were identified in the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum.15 Proteolytic bacteria composed a high proportion of the total bacteria in all regions, but accounted for almost all bacteria in the duodenum. Numbers of bacteria identified from the GI lumen outnumbered those recovered from the mucosa in all segments.15

Infectious Diarrhea in Foals

Bacterial Disorders

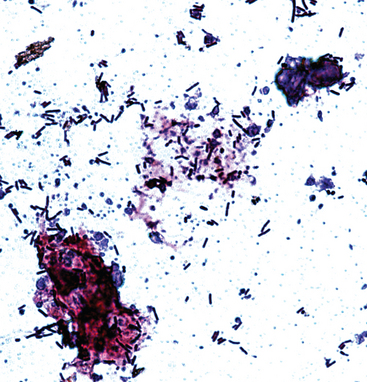

Clostridial organisms can act as primary pathogens in foals, causing disease in individual animals or as outbreaks on affected farms (see Chapter 44). Clostridium perfringens typically affects foals under 10 days of age. Types A and C are most often implicated, with type C resulting in more severe disease, hemorrhagic diarrhea, and higher mortality than type A.16 Type A C. perfringens is typically isolated from the feces of normal foals, but the organism in general is more often isolated from foals with diarrhea.17 A diagnosis is usually confirmed with the combination of clinical signs and culture of the organism from feces, preferably with genotyping of the obtained isolate. Observation of large, gram-positive rods on a fecal Gram stain should prompt the clinician to consider clostridial enteritis16 (Fig. 3-2).

Clostridium difficile has also been implicated as a cause of diarrhea in foals. Disease severity can vary from mild to hemorrhagic diarrhea. As with C. perfringens, C. difficile can be isolated from asymptomatic foals, and thus toxin detection in feces is useful for confirmation of a diagnosis.18

Commercial immunoassays are available for the detection of toxins A and B in feces as well as the enterotoxin of C. perfringens (CPE). Treatment is supportive, with the addition of directed antimicrobial therapy, typically with metronidazole. In some geographic locations, documented metronidazole resistance in C. difficile isolates has prompted therapy with vancomycin in select cases.19

The other predominant bacterial cause of enterocolitis in foals is salmonellosis (see Chapter 38). In addition to diarrhea, affected foals typically display clinical signs of sepsis. Diagnosis is confirmed by aerobic culture of blood and feces. Treatment is supportive and should include directed systemic antimicrobial therapy. Foals with systemic sepsis may develop diarrhea in association with their primary disease, with a reported incidence between 16% and 38%.20–23 Although Escherichia coli is the most common etiologic agent associated with sepsis (see Chapter 6), it is not typically recognized as a primary cause of enteritis or enterocolitis in foals. There is an increased probability of diarrhea in foals with Actinobacillus sepsis compared with foals from which other organisms are isolated.20

Infection of older foals with Lawsonia intracellularis, an obligate intracellular pathogen, results in proliferative enteropathy24–27 and should be considered in weanling-age foals with severe hypoproteinemia (see Chapter 36). Clinical signs include weight loss, ill thrift, depression, colic, peripheral edema, and variable fecal consistency, ranging from soft, normal stool to watery diarrhea. Protein loss can be severe. Diagnosis is based on clinical signs in combination with results of fecal PCR and serum antibody testing. Treatment includes supportive care, predominantly with colloid replacement, and directed antimicrobial therapy with erythromycin estolate and rifampin or chloramphenicol.25,28

Viral Disorders

The most common viral pathogen associated with diarrhea in foals is rotavirus (see Chapter 17). Typically, rotavirus affects foals between 5 and 35 days of age, with most foals at the younger end of this spectrum.29 The most common and obvious clinical sign is diarrhea, and fecal consistency can vary greatly. Other signs relate to disease severity, including depression, anorexia, dehydration, and similar findings. The virus causes blunting of the small intestinal microvilli, with malabsorption and maldigestion. Diagnosis can be confirmed with fecal electron microscopy, which has a significant lag time, or commercial immunoassays, also performed on feces. Treatment is principally supportive, with extra emphasis placed on biosecurity protocols. Quaternary ammonium compounds are ineffective as disinfectant agents for equine rotavirus. The virus is extremely contagious, with morbidity approaching 100% in farm outbreaks. Prognosis is good with supportive care, and mortality is typically low in uncomplicated cases.

Other viral causes of diarrhea occur much less frequently and include coronavirus30,31 and adenovirus32,33 (see Chapters 18 and 16, respectively).

Infectious Small Intestinal Disease in Adult Horses

Etiology and Pathogenesis

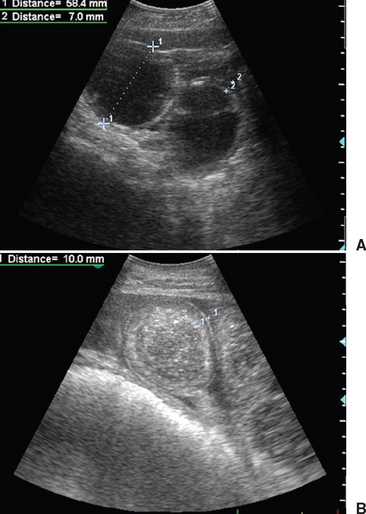

Proven infectious disorders of the small intestine of adult horses are rare. Horses do not appear predisposed to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, which is common in dogs and humans. One equine disorder that has a suspected, but to this point unsubstantiated, infectious origin is duodenitis/proximal jejunitis (DPJ, also known as anterior enteritis or proximal enteritis), a syndrome of small intestinal inflammation characterized by copious quantities of gastric reflux (Fig. 3-3). In most affected horses, an underlying etiology cannot be determined and the syndrome of DPJ may include a wide variety of inflammatory small intestinal disorders resulting in a similar clinical presentation. In some horses, Salmonella spp. or Clostridium spp. are isolated from gastric reflux samples (see Chapters 38 and 44). Recently, toxigenic strains of Clostridium difficile were isolated from the reflux in five of five horses with DPJ and from none of six control horses with other causes of nasogastric reflux.34 Mycotoxins of Fusarium moniliforme may also play a role in some cases of DPJ.35

Clinical Findings

The most characteristic clinical signs in horses with DPJ include moderate to severe pain, which improves after gastric decompression; large volumes of gastric reflux; clinical signs of endotoxemia (see Chapter 37); and small intestinal distention evident on rectal palpation and ultrasonographic examination (Fig. 3-4).

Abnormal clinicopathologic findings in horses with DPJ can include hemoconcentration, neutropenia, acidemia, prerenal azotemia, hyponatremia, hypochloremia, hypokalemia, and increased hepatic enzyme activities.36 Typically, peritoneal fluid has a mild to moderate increase in total nucleated cell count (TNCC, up to 20,000/μL), with a moderate to marked increase in total solids (up to 5 g/dL). However, the nucleated cell count may vary widely. These findings may help to differentiate horses with DPJ from horses with strangulating small intestinal disease, which tend to have higher numbers of red blood cells as well as a higher TNCC. However, the wide fluctuation in results obtained with these disorders may make differential diagnosis difficult in many horses, necessitating exploratory celiotomy.37

Therapy

Treatment of DPJ consists primarily of supportive care, with an emphasis on fluid therapy and gastric decompression. Particular care should be taken to administer maintenance fluid requirements and replace the fluid volume lost through gastric reflux. Therapy should also include nonsteroidal antiinflammatory therapy for analgesic and antiinflammatory effects, as long as renal function remains normal, and directed therapy to combat endotoxemia. If the affected horse’s condition either deteriorates or fails to improve with medical therapy, surgical exploration can be considered.38 Surgical exploration can offer manual decompression of the small intestine and rule out any physical obstruction. In protracted cases or in horses with increased serum triglyceride concentrations, intravenous (IV) parenteral nutritional support should be considered. Prokinetic therapy with erythromycin lactobionate, metoclopramide, bethanechol, or lidocaine may also be considered.39,40

With prompt medical therapy, horses with DPJ generally have a good prognosis for survival. Factors associated with a decreased risk of survival include increased peritoneal fluid protein concentration, increased anion gap,41 and failure to respond to prokinetic therapy within 24 hours.39 Potential complications of DPJ include laminitis, thrombophlebitis, peritonitis, adhesions, pharyngitis or esophagitis, and cardiac arrhythmias.

LARGE INTESTINE

Normal Flora

Much more is known about the resident microflora in the equine large intestine than the small intestine or the more orad portions of the GI tract. The cecum and colon have a large capacity and the capability for extensive fermentation by bacteria and protozoa. Total protozoal concentrations in the large intestine appear to increase in horses fed a diet high in forage, relative to a diet high in concentrate.42 The colon has concentrations of both total and cellulolytic fungi more than 10 times greater than those found in the cecum.42 At least two species of anaerobic phycomycetes capable of digesting plant cellulose and hemicellulose have been isolated from the equine cecum.43 Ruminococcus flavefaciens has recently been identified as the predominant cellulolytic cecal bacterial species.44 At least two types of spirochetes have been identified in the equine cecum.45 Bacteriophages infecting spirochetes within the equine cecum45 and bacteriophage-like particles have been demonstrated in various regions of the large intestine by electron microscopy.46

Acute Diarrhea in Adult Horses

Etiology

The principal infectious agents associated with colitis in horses include Salmonella spp. (see Chapter 38), Neorickettsia risticii (see Chapter 43; equine monocytic erlichiosis, Potomac horse fever), Clostridium difficile, and Clostridium perfringens (see Chapter 44). Aeromonas spp. are often isolated from horses with diarrhea, but their significance has not been fully determined. Parasites are not typically associated with acute diarrhea in adult horses, with the exception of larval cyathostomiasis in Europe and the northern part of the United States and Canada (see Chapter 62

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree