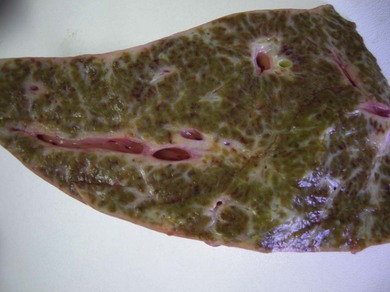

Chapter 3 3.1 Diagnostic approach to liver disease 3.3 Theiler’s disease (acute hepatic necrosis, serum hepatitis, serum sickness) 3.6 Cholangiohepatitis and choledocholithiasis (biliary calculi) 3.8 Iron overload (haemochromatosis) Diseases of the stomach (equine dysautonomia) 3.17 Diagnostic approach to intestinal disease 3.18 Chronic inflammatory bowel disease 3.21 Idiopathic chronic diarrhoea 3.23 Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug toxicity Liver disease is relatively common in the horse, and there are a large number of disorders that can cause hepatic disease (i.e. pathological damage to the liver) (Table 3.1) in both adult horses and foals. However, liver failure is much rarer because the liver has a large reserve capacity and good capacity to regenerate. Liver failure will not occur until 70% or more of the organ has been damaged. The distinction between liver disease and liver failure is important clinically. In view of the large reserve capacity, many horses with mild hepatic disease will make a full recovery given time and removal of the inciting cause. However, if the damage progresses to cause liver failure, then the prognosis for survival is much reduced. Table 3.1 Important causes of liver disease in the horse Hyperammonaemia results when ammonia from portal circulation is not metabolized to urea within the liver and enters the systemic circulation. Raised plasma ammonia affects gluconeogenesis causing utilization of branched-chain amino acids. The resultant decrease in ratio of branched-chain to aromatic amino acids affects neutrotransmission and may give rise to hepatic encephalopathy (see Chapter 11) or, very rarely, peripheral neuropathy which can lead to unusual complications such as gastric impaction (and colic) or laryngeal paralysis. Signs of hepatoencephalopathy may vary from depression to bizarre maniacal behaviour. Common signs include: Accumulation of bilirubin in plasma may result in jaundice. There may be decreased hepatic metabolism of photodynamic phylloerythrin which, when exposed to ultraviolet light within superficial dermal circulation, results in necrotic skin lesions in white areas referred to as photosensitization (Figure 3.1) (see Chapter 13). Pruritus occasionally occurs due to bile salt accumulation in the skin. • Age – in foals, liver failure is associated with rare disorders such as Tyzzer’s disease or portosystemic shunt. Senile cirrhosis occurs in elderly horses. • Multiple cases affected implies ingested hepatotoxin (e.g. pyrrolizidine alkaloid) or, very rarely, liver fluke infection. Also, hyperlipaemia with associated hepatic dysfunction may occur in groups of horses under the same management, and Theiler’s disease is seen as a group disease in North Western USA. • Duration/progression of signs – insidious weight loss is common and non-specific for chronic hepatopathies. Neurological signs associated with hepatic encephalopathy can develop fairly suddenly in chronic advanced liver failure (e.g. pyrrolizidine toxicosis) or, more likely will be the presenting complaint in acute liver failure (e.g. Theiler’s disease). Physical examination: Few physical findings are diagnostic of equine liver disease. Generally the approach is to rule out other possible causes of weight loss, behavioural changes or skin lesions, e.g. signs of enteropathy, primary central nervous system (CNS) disease (Chapter 11) or primary skin disease (Chapter 13). • Jaundice occurs relatively infrequently in equine liver failure but is more likely in acute and/or cholestatic diseases. Horses commonly become mildly jaundiced from anorexia, even when the liver is not diseased. • Mucosal petechial/ecchymotic haemorrhages or bleeding due to clotting abnormalities occur uncommonly. • Peripheral oedema or ascites is rare in equine liver failure. • Photosensitization lesions occur in unpigmented skin, especially the skin of the head (Figure 3.1). Laboratory investigation of liver disease: In the mature horse, leakage of hepatic and biliary enzymes into the circulation, failure to convert ammonia to urea and failure to conjugate bilirubin are generally recognized before failure to produce clotting factors or albumin is recognized. 1. Plasma/serum liver enzymes. glutamate dehydrogenase (GLDH) – liver specific. sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH) – specific, unstable if stored (e.g. postal). lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) – isoenzyme 5 non-specific. aspartate transferase (AST) – non-specific. • Biliary tract damage or obstruction: • An increase in direct bilirubin is a highly sensitive and specific marker of liver failure due to either hepatocellular or hepatobiliary disease. However, mild hyperbilirubinaemia may occur in horses that are anorexic, regardless of the cause. An increase in direct bilirubin of 25% or more of the total bilirubin is suggestive of a predominant biliary disease. Clinically evident jaundice associated with marked unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia but in the absence of other biochemical evidence of liver disease is suggestive of haemolytic anaemia. Septic foals with intestinal ileus sometimes have elevations in direct bilirubin with minimal evidence of hepatocellular dysfunction; treatment should focus on the sepsis and intestinal ileus. • There may be a decrease in blood urea nitrogen and albumin with chronic liver diseases. • Serum or plasma bile acids are elevated in horses with both hepatocellular and hepatobiliary disorders, and elevations can be an early predictor of liver failure when values rise above 30 µmol/L. Unlike for other species, fasting samples are not required in horses to interpret bile acid results, although mild elevations of bile acids (up to 20 µmol/L) may occur as a result of anorexia. • Blood ammonia can also be used as an assessment of liver function. However, rapid and careful sample handling is required. Ideally a control sample should be obtained from a healthy horse and measured simultaneously for comparative purposes. • Dye excretion tests (such as bromosulphophthalein and indocyanine green) are now very rarely used to assess liver function. 3. Other analytes may be altered in hepatic disease, e.g. hypoglycaemia, hypoalbuminaemia, decreased albumin: globulin ratio, and raised concentrations of triglycerides and cholesterol. 4. Clotting function – prolonged prothrombin time. Many of the standard biochemical indices of liver function/damage possess significantly different reference ranges than adult horses. GGT, bile acids and AP, for example, are normally higher in healthy foals than adults. 5. Reference ranges for many of the standard biochemical indices of liver function differ between foals and adult horses. Liver biopsy: In many cases biopsy can provide a definitive diagnosis (which laboratory tests cannot). Liver biopsy is best performed after the liver has been visualized by ultrasonography on either the right or left side. Liver biopsies can be useful to determine the amount of fibrosis, inflammation, and predominant location of disease and for culture purposes. Pre-biopsy evaluation of extrinsic, intrinsic and common clotting function, by measurement of prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) is often recommended. Although prolonged clotting times are rare even with severe liver disease, the risk of haemorrhage is higher in adults with Theiler’s disease and foals with Tyzzer’s disease. Using a 14-cm needle, percutaneous biopsy can also be performed ‘blind’ in the standing horse at the 12th, 13th or 14th right-sided intercostal spaces between the level of lines drawn from the tuber coxa to the point of the olecranon and to the point of the shoulder. Diagnostic ultrasound in liver disease: Transabdominal ultrasonography is best performed with either a 2.5-MHz or 5-MHz transducer. In neonatal foals, 7.5-MHz or 10-MHz transducers are effective. The liver is best imaged from the right, immediately caudal and ventral to the lung. Typical landmarks for imaging the liver are the 6th to 15th intercostal spaces on the right, and the 6th to 9th intercostal spaces on the ventral aspect of the abdomen. In neonatal foals, the liver can also be imaged from the ventral aspect of the abdomen. In adults, the image quality is variable, depending on such factors as the underlying disease, normal age changes (right lobe atrophy in old horses), extent of the lung fields, degree of gas distension of the colon, amount of subcutaneous fat, etc. Healthy liver tissue is less echogenic than the spleen, and has a more prominent vascular pattern. The portal veins can be distinguished from the hepatic veins by the greater amount of fibrous tissue in the walls of the portal vessels. Bile ducts are not visible in the normal liver. Discrete lesions such as abscesses/masses, choleliths, biliary sludge and dilated bile ducts can be visualized, and chronic fibrosis or hepatomegaly can be appreciated. Horses with areas of unpigmented skin may develop photosensitivity. The clinical course may vary from several days to several months, but when sufficient liver damage has occurred to produce functional failure, there may be an abrupt onset of profound clinical signs of hepatic encephalopathy, and in many cases death. The apparent acute onset of clinical illness generally represents the end stage of a chronic, progressive disease process (Figure 3.2). Clinical signs and death may occur up to a year after the contaminated feed was eaten. • Elevation of liver-derived serum enzyme activities (SDH and AST) is associated with active liver damage, but activities may decrease toward normal until the later stages of the disease process when marked elevation may again be noted. • Elevation of GGT and AP activities reflects the focus of the pathological process in the periportal regions and the biliary system. • Serum bile acid concentration is generally increased. • Serum bilirubin concentrations may remain within normal limits until the horse reaches a state of functional failure. • The blood urea nitrogen concentration is generally below normal in horses with functional failure. Cholangiohepatitis is the most commonly encountered, clinically significant form of biliary tract disease in horses. The condition probably begins as a cholangitis, but extension into the periportal region of the liver normally follows (hence the term ‘cholangiohepatitis’ is usually used). It is probable that many mild cases of cholangitis/cholangiohepatitis are asymptomatic, but the condition predisposes horses to chronic, active, inflammatory hepatobiliary disease and the formation of biliary calculi (Figure 3.3). Chronic cholangiohepatitis may frequently be associated with significant intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary calculus formation. Discrete calculi can often be visualized ultrasonographically or at post mortem examination, but some horses with cholangiohepatitis develop a sonolucent ‘sludge-like’ material within the biliary tract. With severe suppurative cholangiohepatitis significant periportal and bridging fibrosis can occur. Clinically significant hepatobiliary disease appears to be more common in middle-aged to old horses. Figure 3.3 Large biliary calculus at post-mortem examination of a horse affected by cholangiohepatitis. Clinical signs are non-specific, and include: • increases in the hepatobiliary enzymes GGT and AP, with moderate increases in the hepatocellular enzymes (AST and SDH). • total serum bilirubin is elevated with the conjugated fraction representing more than 25 per cent of the total. • bilirubinuria may also be observed. • serum bile acids are usually elevated, and blood ammonia concentration may be raised in horses with complete calculus obstruction. Laboratory evaluation provides evidence of liver damage: • elevation of liver-derived serum enzyme activities and marked elevation GGT and AP. • serum bilirubin may be elevated with direct-reacting bilirubin comprising up to 40% of the total. • the urine is positive for bilirubin. • Sedation may be necessary in horses with signs of hepatoencephalopathy. Xylazine or detomidine administered in small doses is usually effective. Doses of sedatives that cause lowering of the head should be avoided if possible as low-head position and hypoventilation may worsen cerebral oedema. Phenobarbital can be used, but diazepam should be avoided since it may worsen hepatoencephalopathy. • Intravenous fluids are probably the most important component of treatment for acute liver disease and hepatic encephalopathy. The intravenous fluids should consist of a balanced electrolyte solution, preferably without lactate, and should be supplemented with potassium 20–40 mEq/L, and 5–10 grams of dextrose per 100 mL. Sodium bicarbonate should be given only if blood pH is less than 7.1 and/or bicarbonate is less than 14 mEq/L. Additional potassium may be given as potassium chloride mixed in molasses and administered per os via a dose syringe. Fresh frozen plasma may be used, but hetastarch or stored whole blood should be avoided. • Attempts should be made to decrease blood ammonia concentration.

Gastroenterology 2. Hepatic and intestinal disorders

Liver disease

3.1 Diagnostic approach to liver disease

3.2 Pyrrolizidine toxicity

3.6 Cholangiohepatitis and choledocholithiasis (biliary calculi)

3.7 Chronic active hepatitis

3.11 Treatment for liver failure