Heidi Banse

Gastric Impaction

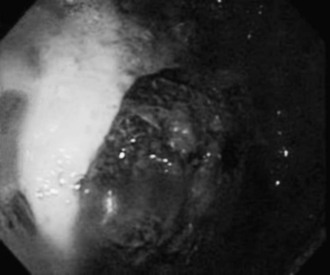

Gastric impaction in the horse is relatively rare, with an estimated prevalence of less than 1% of colic cases. Gastric impactions are characterized as primary or secondary. Primary gastric impactions are caused by functional or anatomic gastric defects, including decreased gastric emptying, acid secretion, or pyloric stricture. Causes of secondary gastric impactions include poor mastication, dehydration, hepatic disease, or any gastrointestinal disturbance that causes generalized ileus. Gastric impactions often occur following consumption of substances that expand upon contact with water, including hay, persimmon fruit (Figure 65-1), bran, mesquite beans, and beet pulp or straw.

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs of gastric impaction range from inappetence to acute colic. Pain is typically mild, but can be severe. In one retrospective study, inappetence was the most common clinical sign (seen in approximately 50% of the horses), followed by acute (35%) or recurrent (35%) colic. Pyrexia, dysphagia, fluid nasal discharge, decreased fecal output, lethargy, weight loss, and hypersalivation have also been reported. In cases of gastric persimmon phytobezoars, diarrhea may occur. Duration of clinical signs is variable, ranging from less than a day to several months.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of gastric impactions can be challenging because of the nonspecific clinical signs, but a history of ingestion of expansive substances should increase the index of suspicion. A diagnosis of gastric impaction is supported by endoscopic identification of a concretion of ingesta after feed withholding for 18 to 24 hours. However, gastric distension can be challenging to assess endoscopically, and feed within the stomach following fasting may simply be an indication of delayed gastric emptying associated with generalized ileus. In cases of colic, rectal examination, transabdominal ultrasonography, peritoneal fluid analysis, and abdominal radiographs will help rule out other differential diagnoses. Horses with gastric impactions may have hematologic evidence of systemic inflammation (leukocytosis, leukopenia, or hyperfibrinogenemia). The reason for this is unclear but presumably is associated with bacterial translocation or peritonitis secondary to gastric wall compromise. Palpation per rectum may reveal medial displacement of the spleen in conjunction with gastric impaction. On occasion, ultrasound has been helpful in identifying gastric distension from feed. However, the accuracy of ultrasound in detection of gastric impactions has not been evaluated. Diagnosis may also be achieved by exploratory celiotomy.

Treatment

Medical management is the preferred treatment for gastric impactions. The most important component of medical treatment is enteral administration of fluids. Frequent administration of low volumes of enteral fluids (about 2 L/hour) may help to hydrate and soften the impaction. Isotonic fluids may hydrate the impaction more rapidly than plain water. Intravenous fluids are typically less efficacious than oral fluids at hydrating gastrointestinal impactions but may be a useful part of the initial therapy in dehydrated horses. Laxatives, including dioctyl sodium succinate (10 to 50 mg/kg given in 2 to 4 L water), magnesium sulfate (0.5 to 1 g/kg in 2 to 4 L water every 24 hours), or mineral oil (2 to 4 L, every 12 to 24 hours), have been used in cases of gastric impaction, although the efficacy of these treatments is unknown. Magnesium toxicosis has been reported in horses following administration of magnesium sulfate, so blood magnesium concentration should be monitored in horses receiving multiple doses. Gastric lavage may be attempted but often yields little improvement. If attempted, gastric lavage should be performed by administering small volumes (2 to 4 L) of water and draining multiple times through a nasogastric tube.

Horses with concurrent gastric ulcers may benefit from gastric ulcer treatment. Acid suppressant therapy (omeprazole, 4 mg/kg, PO, every 24 hours; ranitidine, 6.6 mg/kg, PO, every 6 to 8 hours; or ranitidine, 1.5 mg/kg, IV, every 6 hours) is likely the most effective treatment for ulcers, but antacids (aluminum or magnesium hydroxide, 0.5 mL/kg, PO, every 4 to 6 hours) can transiently increase gastric pH. Sucralfate (20 to 40 mg/kg, PO, every 6 hours) may be used in conjunction with acid suppressant therapy; however, sucralfate has not been demonstrated to promote ulcer healing and should not be used as a sole treatment.

Horses may experience discomfort following initial enteral fluid administration because the impaction may expand with hydration. Retrieval of any excess fluid or gastric contents should be attempted through a wide-bore nasogastric tube if signs of colic develop after administration of fluids. Gastric rupture is a possible sequela of gastric impaction, so careful monitoring of clinical signs and judicious use of enteral fluids, particularly early in treatment, are recommended. In humans with gastric persimmon phytobezoars, partial fragmentation of the bezoar (either through endoscopic fragmentation or partial dissolution) has been reported to result in subsequent small intestinal obstruction.

Primary feed (hay) impactions may resolve within a few days. Concretions of expansive feed, such as persimmon impactions, may require weeks or months of medical treatment before resolving. In cases in which long-term treatment is necessary, small, frequent meals of a complete pelleted feed may provide for nutritional needs without adding to the impaction.

In cases of gastric impaction that are nonresponsive to medical treatment, exploratory celiotomy may be necessary to fragment or remove the impaction. Intraoperative administration of fluids through nasogastric tube and concurrent massage of gastric contents or transmural (gastric) injection of fluid and massage of gastric contents may resolve impactions. The advantage to these procedures over gastrotomy is the presumed decreased risk for peritonitis. However, if these treatments fail, a second surgery may be needed to remove the impaction so that an incision is not made into the fluid-filled stomach. Gastrotomy has been performed successfully in the horse but carries a risk for peritonitis. The advantages of gastrotomy include confirmation of impaction resolution and observation of the stomach for signs of injury.

Treatment of Persimmon Phytobezoars

For persimmon bezoars, enteral administration of cola or cellulase, or intrabezoar injection of acetylcysteine through the endoscope, may help dissolve the bezoars. Successful treatment of phytobezoars (including persimmon bezoars) with intragastric diet or regular cola has been reported in both humans and horses. The mechanism by which cola helps dissolve persimmon phytobezoars is unknown but has been attributed to acidic pH, mucolytic effects of sodium bicarbonate, or disruption of fibers by carbon dioxide. The recommended dose for cola treatment is approximately 24 L/day for an adult light breed horse, either through intermittent intragastric boluses of 2 L every 2 hours or by constant intragastric infusion of 1 L/hour. Caffeinated cola should be used with caution because caffeine toxicosis may occur with high doses. Although laminitis has not been reported after cola treatment in horses, cola has a high nonstructural carbohydrate content, and the potential for laminitis after large doses exists. Cellulase (300 mg/day to 3 g/day) and intrabezoar injection of acetylcysteine (15 to 30 mL, diluted in saline) have been used successfully in humans, but efficacy in horses is not known.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree