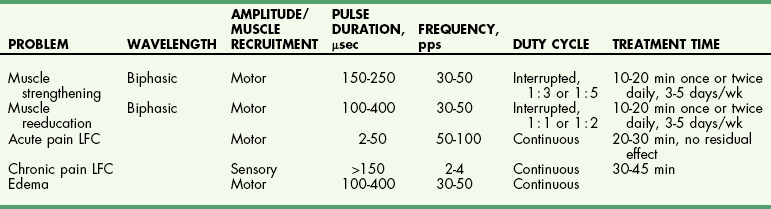

Chapter 11 Physical therapy is the conventional standard of care in human medicine and has proved to aid in the overall physical recovery of patients. Used in conjunction with standard medical and surgical treatment plus proper pain management (see Chapter 12), veterinary rehabilitation can facilitate early and more complete recovery from surgery and trauma. Additionally, physical rehabilitation modalities provide options for treatment of osteoarthritis and other chronic orthopedic and neurologic diseases. Cryotherapy refers to the therapeutic application of cold. Cold is the thermal agent of choice for managing the acute phase of tissue injury because it minimizes inflammatory processes and provides analgesia. Lowering the temperature of skin and underlying tissue causes vasoconstriction, reduces blood flow, and decreases sensory and motor nerve conduction velocity. Cryotherapy is commonly used to treat postoperative inflammation, musculoskeletal trauma, and muscle spasm, and to minimize secondary inflammation following therapeutic exercise. It induces a temperature change in affected tissue of between 1° C and 4° C intramuscularly and between 12° C and 13° C at the skin surface as heat is removed from the body. Typically, return to baseline temperature occurs in 15 to 30 minutes, allowing a significant period of analgesia and inflammation and/or edema reduction. Ice packs, ice massage with homemade ice popsicles, or a cold compression unit (Fig. 11-1) may be used for hypothermia application. First, apply a towel over the site to protect the skin. Apply an ice pack (a freezer bag filled with crushed ice), cold compress, or iced towel to the affected site. If possible, secure the ice pack with a compression wrap to hold the pack in place, compress tissues, and protect the rest of the body from the pack. Pulsed signal therapy (PST) employs magnets to generate low-level electrical fields in the body. PST has been shown to have positive effects on bone and cartilage in vitro; however, clinical efficacy remains controversial (Gupta et al, 2009; Boopalan et al, 2011). Although manufacturers of veterinary PST systems cite several human studies demonstrating the efficacy of PST for the management of osteoarthritis, other studies have shown no benefit (Vavken et al, 2009; Gremion et al, 2009). PST has also been used for the treatment of tendonitis, wound healing, and pain in human surgical patients (Owegi and Johnson, 2006; Gupta et al, 2009). No studies have demonstrated the efficacy of PST in dogs. Neoplasia should be ruled out before treatment is begun because PST potentially may stimulate the growth of neoplastic cells. Lasers are instruments that amplify and focus light into a beam that delivers photons into a specific area. “Cold” lasers, sometimes referred to as phototherapy, are intended to stimulate healing. Low-energy laser therapy uses irradiation intensities that induce minimal temperature elevation (not more than 0.1° C to 0.5° C), if any. This restricts treatment energy to a few J/cm2 and laser power to 500 mW or less. Cold lasers are considered investigational by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which limits their use in humans but not in veterinary patients (Clinical Policy Bulletin, 2010). Evidence has been put forth for the efficacy of cold laser therapy in humans for the treatment of neck pain, tendonitis, osteoarthritis, and other musculoskeletal diseases, and for chronic wound healing (Chow et al, 2009; Chang et al, 2010; Bjordal et al, 2007; Minatel et al, 2009). Cold lasers are being marketed to treat wounds, infections, back pain, and soft tissue injuries. To date, no peer-reviewed clinical trials have evaluated the efficacy of low-level or cold lasers in veterinary patients. Typically PROM is indicated for animals that are unable or are not allowed to actively move an extremity. PROM can be applied to severely debilitated/recumbent patients to minimize complications associated with decreased circulation. This technique is often used to treat muscle soreness from weekend overactivity and as a warm-up for other exercises. PROM is not a substitute for active ROM because it will not prevent muscle atrophy, increase strength, or assist in circulation. Place your hands above and below the joint and gently flex and extend the joint while supporting the limb. Manipulate the joint(s) through pain-free ROM (Figs. 11-2 and 11-3). Slowly extend and flex the joint. Do not force the motion beyond a comfortable level. Hold the stretch for 15 to 30 seconds. Return the joint to normal. Repeat the stretch up to 20 times per session. Manipulate all joints of the affected limb for maximal benefit (Fig. 11-4). Monitor the patient before, during, and after treatment for changes in pain, active ROM, or quality of movement. It is not unusual for range of motion to improve as the patient relaxes. NMES is used most frequently to rehabilitate patients with orthopedic and neurologic disease. Effects of NMES include increasing ROM, increasing muscle strength, and improving muscle tone; decreasing edema and enhancing circulation; and decreasing muscle spasms and pain. It improves muscle strength by increasing muscle contractile proteins and improves muscle endurance by increasing vascularity, aerobic capacity, and mitochondrial size. Electrical muscle stimulation may be used to reeducate denervated muscle. Iontophoresis is the use of electrical stimulation to enhance transdermal medication administration. Clip and prepare the skin over the motor point with alcohol. Apply gel to the skin, and place the electrode (Fig. 11-5). Locate the approximate motor point (area where the motor nerve enters the muscle) for the targeted muscle. With the current on, move the electrode to identify the precise motor point. Mark the point for future reference. Select the parameters for electrical stimulation. First select a wavelength. The wavelength helps determine overall patient comfort. Commonly, symmetric biphasic and symmetric triphasic wavelengths are chosen because smooth and regular wavelengths are most comfortable. Select motor recruitment or sensory recruitment. One muscle may be selected for treatment to promote joint motion, or opposing muscle groups may be treated if joint motion is not desired. Generally NMES is applied for 15 to 20 minutes, one to five times per week (but it can be performed as often as twice daily for 5 days per week; Table 11-1). Muscle soreness may occur with aggressive application of NMES. NMES is most effective when used to enhance contraction and strength during or immediately before active exercise. Therapeutic standing exercises are recommended for debilitated and recumbent animals. Support the animal by holding it physically under the abdomen or pelvis, or use a sling, cart, or wheelchair. Assist the animal to stand for brief intervals (seconds to minutes as tolerated) (Fig. 11-6). Repeatedly help the animal move from a seated or down position to a standing position. Encourage the animal to support as much weight as possible before providing assistance. Be sure to allow sufficient rest intervals between exercises. As the animal’s strength and endurance increase, reduce the amount of assistance provided and increase the duration of activity. Balancing exercises are used to encourage early limb usage, to build muscle, and to improve proprioception and body awareness. Balancing exercises allow the animal to build confidence and to understand that using the leg is no longer painful. Balancing sessions may be started as early as 24 hours postoperatively. Sessions typically start at 1 to 2 minutes twice a day and increase to a maximum of 5 to 8 minutes twice a day. Begin the exercise by placing the animal in a standing position on a stable, nonslippery surface, and very gently shift its weight from side to side (Fig. 11-7). To increase the challenge, place the animal on an unstable surface, such as a couch cushion, water bed, exercise roll, or ball (Fig. 11-8). Eventually work up to using a balance board or raft on water as stamina and endurance increase. Gait training or patterning exercises are used to encourage an animal to move its limbs in a walking motion. Also called assisted walking, this type of exercise can help reeducate the afferent nervous pathway or change a gait abnormality. The exercise is generally applied to nonambulatory animals needing assistance to stand. Gait training can be performed immediately after most surgical interventions. Assist the animal to stand using a sling, harness, or cart. Move affected limbs slowly in a walking pattern, ensuring that each foot contacts the ground appropriately with each step. This exercise may be performed with the animal on the land treadmill (LTM). Alternatively, place the animal in the underwater treadmill (see p. 121), where water supports the patient’s weight, and move the legs through a normal walking pattern. Perform the exercises as long as the animal will tolerate them, twice or three times daily (Fig. 11-9). LTMs are manufactured specifically for dogs, but with proper training, cats may be acclimated. Safety features include side rails and in some cases an overhead hook for a harness. The therapist should be familiar with the manufacturer’s instructions before using the equipment. The speed and incline control offered with the treadmill are helpful for rehabilitating orthopedic patients. Decreased braking and propulsive forces afforded by the treadmill greatly decrease the concussive forces absorbed by the joints. In some cases, the distraction of an unfamiliar environment encourages early weight bearing on the affected limb. Because the animal is able to walk in a constrained area, gait patterning can be performed with less effort on the part of the therapist. Assistive devices such as thera-bands, weights, and off-loading can be used while the animal is on the treadmill. Animals on the treadmill may be more easily evaluated for lameness and stride length alterations. Athletic patients can be worked on the treadmill until occult lameness becomes more evident. Slowly introduce the animal to the treadmill. Depending on the patient, start treadmill exercise for 5 to 10 minutes as early as 12 hours after surgery. Consider the injury, surgical repair, and previous levels of activity when instituting treadmill therapy. Generally, the frequency of treadmill sessions is one to two times a day for 3 to 5 days per week, depending on the patient and the owner. Increase session length as tolerated by the animal. By 4 to 6 weeks after surgery, most animals typically can sustain a 20- to 30-minute session. Observe the patient carefully for progressive lameness after each session, and decrease session length if lameness is noted (Fig. 11-10).

Fundamentals of Physical Rehabilitation

General Considerations

Treatment Modalities

Pulsed Signal Therapy

Cold Laser Therapy

Passive Range of Motion and Stretching

Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation

Therapeutic Exercise

Standing exercises

Balancing exercises

Gait training or patterning

Ground/land treadmill

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Fundamentals of Physical Rehabilitation