Chapter 5 Fluid Therapy

Patients who undergo surgery often require rehydration and electrolyte therapy, particularly in cases of surgery of the gastrointestinal tract. Dehydration and shock are the most important indications for rehydration therapy, especially intravenous therapy. Failure to institute appropriate fluid therapy can result in case failure, regardless of surgical expertise.

Estimating Rehydration Needs

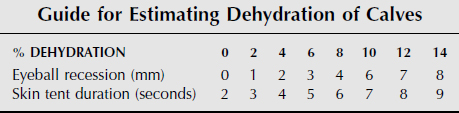

Constable and coworkers showed that the time required for cervical skin to return to its normal position after tenting and the degree of eyeball recession in dehydrated preruminant calves are reasonably accurate methods to determine the state of hydration for calves. Table 5-1, based on this work, is a guide for estimating dehydration. Rehydration by intravenous fluid administration is recommended once dehydration reaches 8%. When skin pinched on the neck takes 6 seconds to return to normal and an eyeball is recessed 4 mm, it indicates the 8% dehydration point has been reached. Similar quantitative studies of the relationship between clinical signs and degree of dehydration for mature ruminants have not been undertaken. In the absence of data to suggest otherwise, the values for estimating dehydration in calves by using skin tent is probably a reasonable guide for mature cattle. However, emaciation can cause eyeball recession and loss of skin turgor, thus making these tests more difficult to interpret in cattle that have recently lost substantial weight. The body weight of mature ruminants can change dramatically based on the amount of ingesta and water in the rumen; therefore estimates of percent dehydration measured as a percent of body weight are probably not very accurate. Therefore from a clinical standpoint, we predict that a cow that is 10% dehydrated will have a normal or near-normal hydration status if 10% of her body weight in fluids is restored. She may still be well under her “normal” body weight because of lack of rumen fill. On the other hand, a cow with fore-stomach distension from vagal indigestion or carbohydrate engorgement may gain weight from fluid sequestered in the third space compartment (inside the rumen) during the disease process but lose significant extra-cellular body water. Even if we could predict the hydration status of a ruminant patient with certainty, factors other than hydration must still be considered in planning and executing the rehydration process. At times an experienced veterinarian can or must break the 8% rule. Sometimes cattle with severe dehydration and normal gastrointestinal function will recover uneventfully with only oral or intraruminal rehydration or with a combination of intraruminal rehydration and a small amount of fluids administered intravenously. In these cases, breaking the rule saves substantial time and expense. However, endotoxemic or hypovolemic cattle or those in shock—with only mild or moderate dehydration—should receive intravenous fluids. Acute strangulating gastrointestinal disease and acute mastitis are examples of conditions that result in this situation. Rapidly correcting or preventing shock is particularly important if a standing surgical procedure is planned. Finally, patients with fatty liver, chronic or refractory ketosis, and pregnancy toxemia may benefit from intravenous glucose therapy regardless of hydration status.

A flow rate of less than 80 ml/kg/hr has been recommended for calves because of studies of central venous pressure in clinically dehydrated calves. Similar studies have not been performed to determine the maximum safe flow rate in mature cattle or small ruminants. However, significant elevation in central venous pres-sure occurred when approximately 40 ml/kg/hr of an isotonic crystalloid was administered intravenously to dehydrated cattle with experimentally induced intes-tinal obstruction, even though no clinical signs were observed. Although this is a much slower flow rate than the maximal flow rate recommended for calves (80 ml/kg/hr) and dogs (90 ml/kg/hr), a 20 L/hr total flow rate for an average dairy cow is a volume difficult to achieve with a single 14-gauge intravenous catheter. Therefore in most situations, intravenous fluids can be administered to mature cattle through a 14-gauge catheter as quickly as they will flow. Exceptions include cattle with heart disease, oliguric renal failure, and hypoproteinemia and those in recumbency.

Choice of Solution

FLUID THERAPY IN CATTLE WITH METABOLIC ACIDOSIS

Although relatively few in number, those conditions in cattle that are consistently associated with acidosis in ruminants are important to remember. Acidosis is the norm for calves with diarrhea and dehydration but not for other sick calves such as those requiring surgery for umbilical masses, fractured limbs, or gastrointestinal diseases. Calves with abomasal and intestinal surgical diseases are similar to mature cattle in their metabolic abnormalities. The most consistent causes of acidosis in cattle older than 1 month of age include carbohydrate engorgement and choke or dysphagia. Carbohydrate engorgement is the only condition that usually causes acidosis and may also require surgery. Carbohydrate engorgement results in systemic acidosis because large amounts of volatile fatty acids and lactic acid are produced by bacterial fermentation. Both D- and L-lactic acid are produced, but only the L isomer is efficiently metabolized by mammalian tissues. Choke or other causes of salivary loss also cause acidosis, because ruminant saliva is rich in bicarbonate. Diarrhea, fatty liver disease, severe ketosis, and urinary tract disease are relatively common diseases that have the potential to cause serious acidosis. In the author’s experience, cattle and small ruminants with urethral obstruction or uroperitoneum are unpredictable in their acid-base and electrolyte status. Some diseases usually associated with alkalosis may be accompanied by acidosis in their later stages. These include abomasal volvulus, intussusception, and torsion of the mesenteric root.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree