CHAPTER 8Fertility Expectations and Management for Optimal Fertility

The aim of commercial horse breeders is to achieve a live foal every year from their brood mares. Although small family bands of feral horses and native ponies may sometimes achieve this, most populations of commercial brood mares have conception and pregnancy failures that result in some mares entering the next breeding season not pregnant, i.e., “barren.” Assuming normal stallion fertility and adequate management, in most cases this is a matter of sporadic mare subfertility, most commonly associated with obstetric injuries, age-related genital tract disease, or managerial problems. True infertility and epidemic subfertility (e.g., epidemic venereal infections or viral pregnancy failures) are uncommon in mares.

It is the responsibility of the equine theriogenologist to do the following:

FERTILITY EXPECTATIONS

Historically, it has been suggested that the equine species inherently achieves relatively low fertility figures and that domestication makes matters worse. With good management, this is not the case. Mare fertility results vary between populations. The 2003 Weatherbys’ Statistical Review1 records that 23,136 Thoroughbred mares were mated by 783 registered Thoroughbred stallions at stud in the United Kingdom (UK) and Ireland. After excluding those mares for which no returns were made, those that were exported or that died, the pregnancy rate (number of mares pregnant/number of mares bred) was 89.30%, the live foal rate was 82.04%, the gestational failure rate was 7.42%, and the barren mare rate was 10.70%. In well-managed populations of Thoroughbred horses, pregnancy rates in excess of 90% and live foal rates in excess of 80% can be achieved.2 Occasionally, young fashionable stallions, covering between 60 and 80 mares, achieve 100% pregnancy rates during a breeding season. Although similar statistics are not published for North America, there is no reason to suspect that results are substantially different. These are now the targets for both equine stud farm clinicians and stud managers. Because the only accurate measure of fertility is pregnancy rate per cycle, any figures such as those above are also related to breeding opportunity (i.e., number of cycles the mare is available to be bred). This is governed by not only gestation length but economic considerations of when a late foal may not be financially viable. If people are prepared to keep breeding outside what would be termed a normal breeding season, then even better figures can be expected.

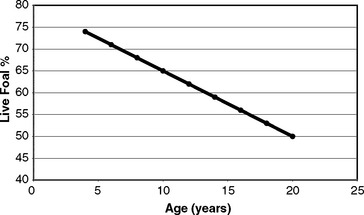

Population statistics help little when considering aspirations for individual mares. Weatherbys’ data demonstrates a linear decline in the fertility potential of mares with age3 (Figure 8-1). During the years researched, the live foal rate of 4-year-old mares was approximately 75%, whereas that of 20-year-old mares was approximately 50%. It is vital that clinicians, stud managers, and owners understand that age has a major and irrevocable limiting effect on a mare’s fertility potential.

Figure 8-1 Live foal percentage with age of Thoroughbred mares.

(Original data from Weatherbys’ Returns for Mares 1973-77.)

Preparing Barren Mares for Next Season

In order to achieve maximal breeding efficiency, all barren mares should receive a thorough examination after the end of the breeding season4–8 and before they go into winter anestrus (e.g., in September [northern hemisphere]), with the following aims:

The Autumn Barren Mare Examinations and Treatments

Examination of the Vulva and Perineum

The conformation of the mare’s perineum and the integrity, shape, and angle of slope of her vulva in relation to her anus is first evaluated to determine if she is likely to have pneumovagina (i.e., she requires Caslick’s vulvoplasty surgery to be performed)9–11 (Figure 8-2). Sometimes, small fistulas (Figure 8-3) are found in the vulval scar after surgery, and these need to be repaired. If the mare’s perineal shape is very poor to the extent that Caslick’s operation is insufficient to prevent pneumovagina, Pouret’s perineal reconstruction operation (Figure 8-4) may be recommended.10–12 The vulval lips are examined for signs of accidental injury leading to incompetent closure. For broodmares, all vulval injuries need careful repair and successful reconstruction to avoid incompetent closure leading to pneumovagina. The vulval lips should be manually separated while the examiner pays attention to aspiration of air into the vagina. In mares with a dysfunctional or weak vestibulovaginal fold, separation of the vulval lips creates a characteristic sound when air is aspirated into the vagina. These mares should be considered to be prone to pneumovagina.

In the UK, Ireland, France, Germany, and Italy, samples are routinely collected from the urethral opening, clitoral fossa, and sinuses (Figure 8-5) for annual screening for the potential equine venereal disease organisms Taylorella equigenitalis, Klebsiella pneumoniae (capsule types 1, 2, and 5), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, as recommended by the Horserace Betting Levy Board’s Code of Practice for the Control of Equine Venereal Diseases. These pathogens may exist in all of these sites and, if found, constitute carrier status.13,14 Carrier mares are excluded from mating until they have been successfully treated and have been proven so by repeated follow-up culturing. T. equigenitalis is sensitive to environmental conditions, and samples should be placed into Amies charcoal transport medium immediately after collection to preserve the organism during transportation to the diagnostic laboratory. The samples should not be subjected to high or low temperatures during transportation.

Vaginoscopic (speculum) examination

The cervix and vagina are examined, via a sterile vaginoscope (speculum), for their appearance in relation to cyclic state (moist, pink, and relaxed in estrus; dry, pale, and tight in diestrus) and for signs of injury, incompetence, discharge, and/or vaginal urine pooling.15 Cervical lacerations that impair normal function, particularly closure, always carry a poor prognosis for future breeding. Some require attempts at surgical repair,16–18 but such mares often remain “high risk” for ascending placentitis, which often results in abortion or the birth of an impoverished foal.19 Other cases heal sufficiently to allow functional closure without surgical interference. In such cases some clinicians recommend that the mare is supplemented with oral progestagens (altrenogest), to aid tight cervical closure, on empirical grounds.

If the mare is in estrus, samples are collected from the endometrium, through the open cervix, and also directly via a sterile speculum (Figure 8-6) for cytologic screening for inflammation (the presence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) [i.e., PMNs in a smear test]), for the equine venereal disease organisms T. equigenitalis, K. pneumoniae (capsule types 1, 2, and 5), and P. aeruginosa, and for any of the multitude of opportunist pathogens (most commonly β-hemolytic streptococci [i.e., Streptococcus zooepidemicus], Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus, and the anaerobe Bacteroides fragilis).13,20 These opportunist organisms are only considered to be of significance (i.e., causing endometritis) if there is cytologic evidence of inflammation in the smear sample.21–23

Figure 8-6 Endometrial culturette being taken from an estrous mare via a sterile disposable vaginal speculum.

Rectal Palpation and Ultrasonographic Examination

During estrus, the uterus has minimal palpable tone and, especially in early estrus, endometrial edema4,5 delineates the endometrial folds on ultrasonographic examination.24–26 During diestrus, the normal uterus should have uniformly palpable tone and no palpable enlargements. Ventral dilations (areas of fold atrophy and myometrial stretching) may contain luminal fluid accumulations that may be either hypoechoic or hyperechoic on scan, the former indicating clear fluid and the latter indicating hemorrhage or, more commonly, inflammatory fluids. In pyometra, which is less commonly seen in mares than some other species, the uterus is uniformly enlarged, palpably distended or “doughy,” and contains particulate fluid, giving a “scintillating” hyperechoic ultrasonographic appearance (Figure 8-7).

Equine ovaries are highly variable in size and activity depending on cyclic state.24 During estrus they may be large and contain follicles in varying stages of development, in addition to old, nonfunctional corpora lutea.27 During diestrus there will be at least one functional corpus luteum in addition to follicles in varying stages of development. During anestrus they will be small and inactive, containing neither active follicles nor corpora lutea.

The most commonly diagnosed ovarian abnormality is the granulosa cell tumor (GCT).28,29 This benign tumor causes one ovary to enlarge, sometimes enormously, and appear full of cysts on ultrasonographic examination (Figure 8-8), while the other ovary is characteristically inhibited and becomes small, hard, and inactive. Granulosa cell tumors are hormonally active, and a clinical diagnosis can be supported by measuring the mare’s blood hormone profile. Diagnostic assays to detect granulosa cell tumors include inhibin, testosterone, and progesterone.30 In a single blood sample of a mare with a granulosa cell tumor, α-inhibin is elevated in approximately 90% of cases, serum testosterone in approximately 50% of cases, and progesterone concentrations should be below 1 ng/ml because these mares are mostly not cycling.30,31 There have certainly been enough reports of cyclicity with early cases of GCT to have caution about acyclicity.32

True cystic ovarian disease is rarely confirmed in mares. Occasionally mares hemorrhage excessively into an ovary after ovulation, causing enlargement and pain. A typical homogeneous hyperechoic ultrasonographic appearance of the blood clot allows the diagnosis to be confirmed (Figure 8-9). Most cases resolve with time, but occasionally pain cannot be controlled without removing the affected ovary surgically. Rarely, large ovarian hematomas are at risk of rupture, with fatal peritoneal exsanguinations, so persistent or uncontrollably painful ovarian hematomas should be treated by unilateral ovariectomy. Ovulation failure is a normal physiologic event for the mare during the spring and fall transition periods, but it may also occur occasionally in the cycling mare. Persistent anovulatory follicles (PAFs) are large (5 to 15 cm in diameter) and may result in prolonged interovulatory intervals. The cause of ovulation failure is not fully understood but has been suggested to be endocrine in nature. PAF has been reported to occur in approximately 8.2% of estrous cycles, and the incidence was found to increase with age.33 PAFs may contain blood, which can be detected ultrasonically as scattered free-floating echogenic spots within the follicular fluid (Figure 8-10). Eventually the hemorrhage will organize into echoic fibrous bands traversing the follicular lumen. The majority of PAFs develop into luteal tissue, which can be confirmed by elevated plasma progesterone concentrations. Luteinized PAF can be treated with prostaglandins, and nonluteinized PAF will regress spontaneously in 1 to 4 weeks. Pregnancy obviously will not occur if the follicle becomes hemorrhagic or luteinized without ovulating (see Chapters 12 and 13).

Endometrial biopsy

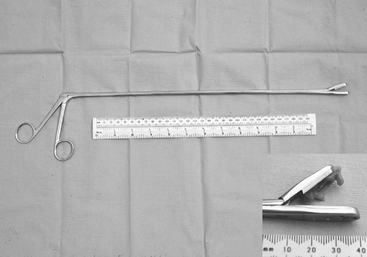

Special long (55 cm) basket-jawed forceps are essential to provide interpretable endometrial biopsy specimens34–37 (Figure 8-11). Unfortunately, specimens obtained via endoscopic biopsy instruments are inadequate for histopathologic appraisal. Nonpregnancy must be confirmed before biopsy. One biopsy taken from a midhorn region is diagnostically representative unless there are palpable uterine abnormalities, when more than one sample should be taken.37–38 A mid-diestrual biopsy is recommended as a routine. The sample is retrieved carefully from the instrument with fine forceps or a needle to avoid artifactual damage and then placed into fixative without delay. If the mare is not in estrus and a specimen for bacteriologic examination was not collected via the cervix, then the inside of the biopsy forceps should be cultured immediately after removal of the tissue specimen. On some occasions, additional tissue (usually an adjacent endometrial fold) is retrieved, not required for fixation for histopathologic examination, and this can be used for bacteriologic examinations. Bouin’s fluid is preferred as histopathologic fixative for reproductive tissues in general and endometrial samples in particular because their high water content leads to excessive artifactual shrinkage in more conventional fixatives (i.e., formol saline). The fixed tissues should be processed for microscopic examination and interpreted at a laboratory that has specific experience with equine endometrial biopsy samples and with equine gynecology.

Cyclic histology.

The microscopic architecture of the endometrium reflects the hormonal status of the mare, so changes that occur during estrus, diestrus, and anestrus can be classified accordingly.37

Histopathology.

Microscopic pathologic abnormalities are usually mixed, so specific changes are classified and their significance is assessed in terms of the mare’s age and gynecologic history.37 They can be conveniently classified as inflammatory (acute and chronic endometritis) and noninflammatory conditions, including endometrial hypoplasia, hyperplasia, and chronic degenerative conditions.

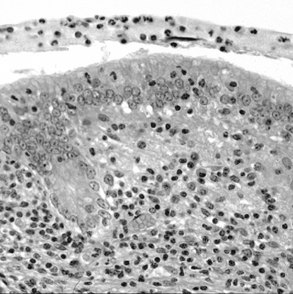

Persistent superficial (acute) endometritis.

Persistent superficial (acute) endometritis is diagnosed by the presence of PMNs (Figure 8-12) and, in severe cases, luminal epithelial degenerative changes, in endometrial biopsy samples taken at any stage of the nonpregnant mare’s cycle.34–37 It is recognized that as mares age and suffer the gynecologic and obstetric effects of a busy breeding career, their natural uterine defense mechanisms become less competent and they become more susceptible to recurrent/persistent acute endometritis.39,40 These defense mechanisms involve local endometrial factors and myometrial function.41–44

Persistent breeding-induced endometritis may resolve spontaneously with sexual rest. Waiting for this to happen is often not practical during a short breeding season, and treatment options include the intravenous administration of 10 to 25 IU oxytocin and/or uterine lavage with a large volume (1 to 2 L) of a buffered saline solution at 6 to 12 hours after breeding. The mare should be considered susceptible to recurrent endometritis each time she is mated, and appropriate prophylactic measures should be taken. Infectious endometritis is treated with local infusions of appropriate nonirritant, water-soluble antibiotics (e.g., ceftiofur sodium is recommended as a useful “first choice,” although choice of antibiotics varies among clinicians, on grounds of availability, experience, and cost).45

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree