Chapter 33 FELINE REPRODUCTION

THE QUEEN

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

The vulvar labia of the queen (female cat) are relatively nonresponsive to estrogen and thus remain small and covered with hair during proestrus and estrus, in contrast to the dramatic increase in size seen in bitches (female dogs). Also different from that in the bitch is the relatively straight horizontal anatomy of the vestibule of the vagina, the vagina, and the cervix of the queen. The vestibulovaginal junction is narrow and inelastic. Inspection of this area requires anesthesia and use of a rather small endoscope (3 mm) equipped with a device for insufflating the vaginal lumen (Shille and Sojka, 1995).

THE ESTROUS CYCLE

Onset of Puberty and Optimal Breeding Age

The optimal breeding age for cats is between 1.5 and 7 years. Females older than 7 to 8 years tend to cycle irregularly, have smaller litters, and have more problems with abortions and congenital defects. Young cats (<1 year of age) may also have irregular cycles and be less predictable in their sexual behavior.

Seasonality of the Estrous Cycle

Artificial light can alter the normal ovarian activity in cats. Those cats maintained with a minimum of 10 hours of artificial light (equivalent to a 100-watt bulb in a 4- × 4-meter room) may cycle throughout the year (Shille and Sojka, 1995). The effect of light on the estrous cycle of house cats can be quite complicated. Pet cats usually do not receive a consistent light pattern because of their exposure to both natural and artificial sources. The artificial lighting in a home may not always result in predictable ovarian cycles, although subjectively, most of these queens do not cycle in October, November, or December.

It has been suggested that the interestrous periods may lengthen during rather warm temperatures (Concannon and Lein, 1983). In our colony of cats, this has been true. However, the effect of heat and/or humidity on ovarian function remains subjective and depends, to some degree, on individual adaptation to extremes in the environment. Long-haired breeds seem to be more sensitive to the photoperiod than short-haired cats, with 90% and 40% showing winter anestrus, respectively (Banks, 1986; Shille and Sojka, 1995).

Phases of the Estrous Cycle

Proestrus

CLINICAL SIGNS AND DURATION.

Proestrus is not observed regularly in queens. Rather, they typically proceed from an apparent anestrous or interestrous condition directly into estrus (standing heat). In one study, proestrus was noted in only 27 of 168 cycles (Shille and Sojka, 1995). The clinical signs associated with the onset of proestrus are changes in behavior consisting of continuous rubbing of the head and neck against any convenient object, constant vocalizing, lordosis posturing, and rolling.

The proestrual cat can be distinguished from one in estrus when she is placed with a male cat. During an observed proestrus, the queen may be less sexually demonstrative than is noted during the subsequent estrus; she does show estrus behavior but does not allow the male to mount. Recognition of proestrus is difficult because the signs may be subtle (affectionate behavior may be the only sign), and duration is only 0.5 to 2 days (Shille and Sojka, 1995). Many of the typical proestrual changes seen in the bitch are not observed in the queen (i.e., in the dog, proestrus has a duration of 5 to 9 days, vaginal bleeding, swelling of the vulva, and consistent changes in vaginal cytology).

VAGINAL CYTOLOGY.

Technique.

Vaginal cytology is not a commonly used procedure in queens. This is primarily because the queen enters an obvious estrus abruptly and because the patterns seen on exfoliative vaginal cytology are not always clearly demarcated. Vaginal exfoliative cytology smears from the queen can be obtained as described for the bitch (see Chapter 19). The assistant usually grasps the queen by the scruff of her neck and holds her down on her elbows. The tail is held in the assistant’s other hand, to raise the rear quarters slightly and allow visualization of the vulva. The veterinarian separates the lips of the vulva and can simultaneously raise the perineum slightly. A sterile cotton swab, moistened with saline, is placed into the vaginal vestibule and guided into the vaginal vault along the dorsal surface of the tract. The swab is gently rotated in both directions and smoothly withdrawn.

Terminology.

The stained slide is studied microscopically at low power to obtain an impression of the degree of “clearing” on the slide. Clearing is defined as the absence of noncellular debris and of eosinophilic or basophilic strands of mucus, as well as a lack of coalescence of vaginal cells into sheetlike aggregates. Estrogen “liquefies” vaginal mucus in cats. Vaginal epithelial cells can be closely examined at higher magnification. These cells can be classified using the categories described in Chapter 19. These categories include parabasal, intermediate, superficial (cornified), and anuclear superficial cells.

Interpretation.

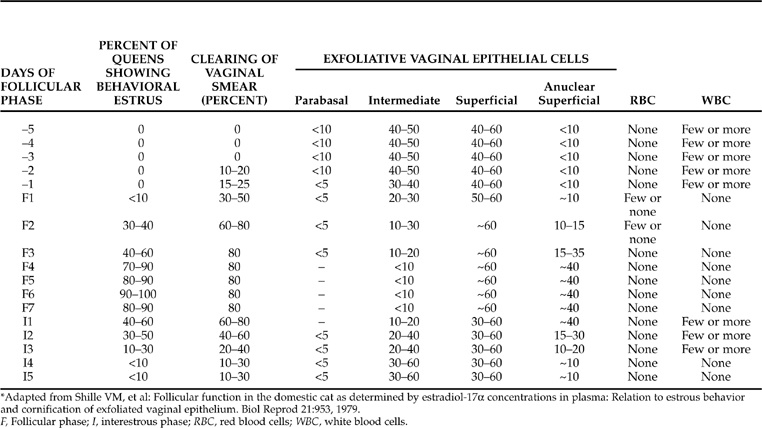

It has been suggested that clearing of the background on a vaginal smear may be the most sensitive and consistent indicator of estrogen activity in the queen (Shille and Sojka, 1995) (Table 33-1). The vaginal epithelial cells become easier to visualize in association with the reduction and the absence of debris. Clearing of the vaginal smear is observed 2 days before the onset of the “follicular phase” in approximately 10% of queens. Clearing is observed in one-third of all estrous cycles before estrus behavior is noted and in more than 90% of estrous cycles during the follicular phase. If clearing is seen on vaginal cytology prior to the onset of estrus behavior, it is consistent with the occurrence of a brief proestrus period.

Cytologically and clinically, proestrus can be defined as starting with evidence of clearing on vaginal cytology smears and ending when the queen allows a tom (male cat) to mount and breed her. Progressive changes in the morphology of vaginal epithelial cells correspond with increasing follicular estrogen secretion rates. The proportion of anuclear superficial cells consistently increases above 10% on the first day of the follicular phase. The proportion of nucleated superficial cells remains relatively constant whereas intermediate and parabasal cell numbers decline (see Table 33-1). Erythrocytes and leukocytes are not often seen in vaginal smears, the former occurring during the early follicular phase and the latter seen occasionally at the end of the follicular phase (Shille et al, 1979).

Estrus and the follicular phase

DEFINITION OF FOLLICULAR PHASE.

The mean length of the follicular phase is approximately 7.5 days and ranges from 3 to 16 days. Coital contact, with or without induction of ovulation, does not alter the duration of the follicular phase. The follicular phase of queens that experience coitus and induced ovulation averages 7.0 days. Queens that experience coitus but do not ovulate have follicular phases that average 7.2 days, whereas those with no coital stimulation have an average follicular phase of 7.7 days (Shille et al, 1979).

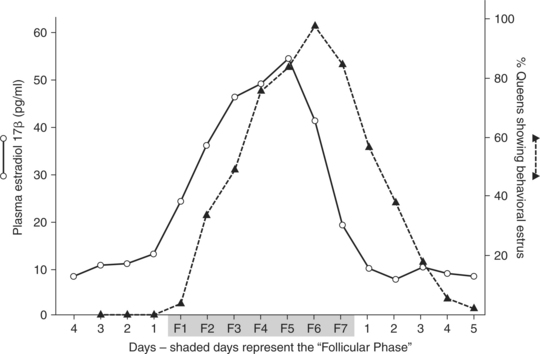

During the follicular phase, the plasma estrogen concentration rapidly increases, remains elevated for 3 to 4 days, and abruptly begins to decline. The plasma estrogen concentration 1 day prior to the start of the follicular phase is below 12 to 15 pg/ml. The first day of the follicular phase is associated with estrogen concentrations of approximately 25 pg/ml, rising to approximately 45 pg/ml on day 3, slightly above 50 pg/ml on day 5, from 20 to 25 pg/ml on day 7, and usually back to 10 pg/ml on day 8. Because the mean estrogen concentration on day 8 is below 15 pg/ml, this actually represents the first day of the interestrous interval, assuming that ovulation was not induced. The mean peak follicular phase plasma estrogen concentration is slightly greater than 50 pg/ml, but it may range from levels near 25 pg/ml to those above 80 pg/ml (Shille et al, 1979).

POLYESTROUS CYCLES VERSUS FOLLICULAR PHASES.

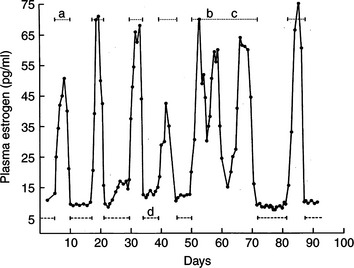

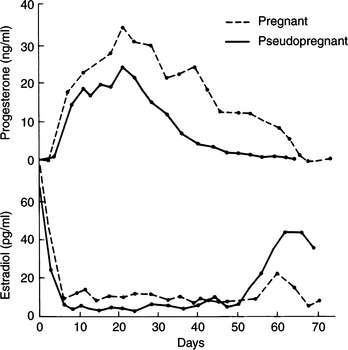

The queen has polyestrous breeding seasons. This means that the average queen repeatedly exhibits estrus behavior in a given season. These estrus periods are associated with recurring follicular phases, but not necessarily in a 1:1 ratio. Generally, each period of peak estrogen concentration is followed by a return to baseline concentrations (Fig. 33-1). Cats have repeating distinct waves of follicle development, maturation, and degeneration.

ESTRUS BEHAVIOR AND ITS RELATION TO THE FOLLICULAR PHASE.

Estrus behavior in the queen can be correlated with increases in plasma estrogen concentration associated with each follicular phase. Estrus behavior is exhibited by 10% of queens on the first day of their follicular phase. The proportion of queens demonstrating estrus behavior then gradually increases until almost all queens show estrus behavior the day before the follicular phase ends (Fig. 33-2). Estrus behavior continues in many queens beyond the end of the follicular phase. Studies on days 1, 2, 3, and 4 after the end of the follicular phase revealed that approximately 60%, 40%, 20%, and 5% of the cats, respectively, continued to exhibit estrus behavior (Shille et al, 1979).

DURATION OF ESTRUS BEHAVIOR.

Average.

The average duration of estrus behavior in the queen is approximately 7 days. There is a wide range of duration, however, and healthy fertile queens may exhibit estrus for as little as 1 day to as long as 21 days. Queens experiencing coitus (whether or not they subsequently ovulate) are in estrus for approximately 8.5 days. Queens that do not have coital contact are in estrus for only 6 days on average (Shille et al, 1979).

Effect of personality on exhibition of estrus.

Absence of behavioral estrus or extreme prolongation of estrus behavior has been and is observed during regularly recurring “normal” follicular phases in healthy cats. Failure to manifest estrus behavior at expected times, predicted by plasma hormone (estrogen) concentrations, has been seen in a few queens thought to be timid and at the lower end of the “social scale” (Shille et al, 1979). However, this personality trait is not always obvious in a queen with active follicular phases but no behavioral estrus. It is difficult to simply label these queens abnormal. Many queens failing to exhibit behavioral estrus during one season may appear normal in subsequent seasons.

Prolonged estrus.

Prolonged estrus behavior is another trait occasionally seen in queens that may later be shown to be fertile and otherwise normal. In some cases, prolonged estrus is the result of overlapping waves of maturing follicles and persistent exposure to increased plasma estrogen concentrations (see Fig. 33-1). However, prolonged or continuous estrus behavior is also seen in cats experiencing distinct, repeated follicular phases. These cats have estrogen concentrations indistinguishable from those observed in queens exhibiting the more typical, repeated sexual receptivity patterns. The reason for the lack of coordination between sexual behavior and plasma estrogen concentrations in a small percentage of queens remains, for the present, unexplained.

VAGINAL CYTOLOGY.

Interpretation.

Two major findings are observed in vaginal smears from queens in estrus. The first change is the background clearing, and the second is reapportionment of the percentage of each type of vaginal epithelial cell. Background clearing is defined as the absence of noncellular debris and eosinophilic or basophilic strands of mucus, allowing the vaginal epithelial cells to be easily visualized. This process is due, in part, to vaginal mucus being liquefied by estrogen. Clearing begins before the onset of the follicular phase in approximately 10% of queens, and one-third of the females studied had cytologic clearing prior to their showing any evidence of estrus behavior. During the follicular phase, at least 90% of the vaginal smears have clear backgrounds. This clearing of the vaginal smear continues in some queens after the follicular phase ends, with 20% of smears continuing to show clearing 5 days later (Shille et al, 1979). Vaginal clearing is easily recognized on the smear and is one of the most consistent alterations, other than blood hormone (estrogen) concentrations, that allow identification of an actively cycling queen.

Progressive changes are seen in the relative proportion of the types of vaginal epithelial cells during estrus (see Table 33-1). The anuclear superficial cells increase to 10% of the total on the first day of the follicular phase and continue to increase in number, reaching approximately 40% of the total from the 4th through 7th days, before slowly returning to less than 10% by the 12th to 13th day (5th to 6th day after the end of the follicular phase). Intermediate cells decrease in number, from approximately 40% to 50% of the total during the interestrous period to less than 10% during the 4th through 7th days of the follicular phase. Parabasal cells disappear during the follicular phase, returning to 5% to 10% of the total 5 days after the follicular phase has ended. The nucleated superficial cell maintains its 40% to 60% proportion of the vaginal epithelial cell population throughout the follicular phase (see Table 33-1) (Shille et al, 1979).

The interestrous period

DEFINITION.

Cats are polyestrous and have repeated phases of sexual receptivity (estrus) throughout the season of ovarian activity (see Fig. 33-1). The phases of sexual activity are associated with “waves” of follicular function separated by brief periods of sexual or reproductive inactivity. The ovaries are believed to be hormonally inactive during the periods between active follicular waves. These periods of inactivity are the “interestrous intervals” or “interestrous periods.”

HORMONAL CHANGES AND DURATION OF THE INTERESTROUS PERIOD.

Effect of plasma estrogen concentration.

The interestrous period follows cessation of follicular function, which is characterized by an abrupt decline of plasma estrogen concentration to levels below 20 pg/ml. The estrogen concentration remains at the low, or basal, level for the duration of the interestrous period, which averages 8 days and ranges from 2 to 19 days (Shille and Sojka, 1995).

Estrus spanning two or more follicular phases.

Occasionally, queens appear to miss an interestrous interval (i.e., estrus activity spans two or more follicular phases despite typical cyclic follicular function; see Fig. 33-1). These queens do experience a hormonal interestrous period but not the behavioral interval one would expect. In some cats, the estrus behavior spanned interestrous intervals with typical basal plasma estrogen concentrations below 20 pg/ml. The estrogen surges during their follicular phases were not, as a rule, different from those seen in the average cat in behavioral interestrous. In other queens, however, cyclic estrogen fluctuations were observed in which the lowest estrogen concentrations remained above the 20 pg/ml plateau. In this latter situation, persistent estrus behavior, without an interestrous interval, is easier to comprehend because the queen is constantly under the influence of follicular estrogen secretion.

VAGINAL CYTOLOGY.

During the interestrous period, nucleated superficial and intermediate vaginal epithelial cells again dominate the smears. The percentage of the various cell types remains static throughout this phase (see Table 33-1). The average numbers of each cell type, identified in one study during the interestrous interval, were parabasal cells, 2%; intermediate cells, 48%; superficial cells, 46%; and anuclear cells, 4% (Shille et al, 1979). Fluctuations in cell type were seen, but these were not typically dramatic and would not be confused with the changes consistent with estrus. Additionally, background debris is obvious on the vaginal smear of a queen in the interestrous period. Background debris interferes with the ability to visualize vaginal epithelial cells.

Anestrus

SEASONALITY AND DURATION.

It is possible to delay the onset of anestrus in cats by maintaining them in at least 10 hours of artificial light (equivalent to that provided by a 100-watt bulb in a 4- × 4-meter room); this regimen causes some queens to cycle throughout the year (Concannon and Lein, 1983). Some queens, however, still may enter anestrus during November and December, despite artificial light supplementation. The effect of the artificial light exposure experienced by pet cats living indoors has not been evaluated.

PHYSIOLOGY OF OVULATION

Coital Induction of Ovulation

Vaginal stimulation by the penis of the tomcat is followed immediately by an increase in neural activity within areas of the hypothalamus that are known to contain large amounts of GnRH. Release of this GnRH is thought to cause the surge in serum LH that follows vaginal stimulation in induced ovulators, such as the cat. LH surges have been shown to occur within 15 minutes of copulation in cats (Concannon et al, 1980; Johnson and Gay, 1981).

The measured surges in serum LH have been correlated with the number of copulations. Maximal LH levels are attained 4 hours after the onset of 8 to 12 copulations. Serum LH concentrations return to basal levels 24 hours later. Peak serum LH concentrations were significantly lower when the queens were allowed to copulate only four times during a 4-hour period. Peak LH concentrations were even lower when only one copulation was allowed. Ovulation was associated with LH concentrations that were higher than when ovulation failed to occur (Concannon et al, 1980).

Each copulation does result in a release of LH, which may or may not be sufficient to cause ovulation. Fewer than 50% of queens in full estrus ovulate following a single breeding. This must be contrasted with the fact that most queens do ovulate following four or more copulations. Copulations may continue for several days, and major LH surges occur day after day. LH release becomes negligible following 2 to 4 hours of copulation in any 24-hour period. Ovulation occurs approximately 24 hours after the rapid release of LH (Concannon and Lein, 1983). Some queens may not release adequate LH concentrations to induce ovulation despite repeated matings with proven fertile tomcats. However, mating several days later during the same estrus, with the same male, may result in ovulation.

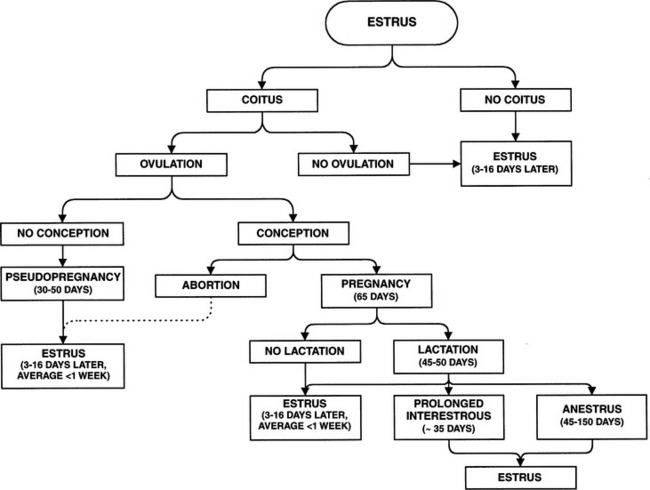

Variability in Induction

The outcome of each feline estrous cycle usually (not always) depends on the queen’s contact with a male. Four distinct possibilities are recognized (Fig. 33-3): first, an anovulatory cycle may occur in which no contact occurs with the male during estrus; second, an anovulatory cycle may occur in which coital contact with the male is insufficient (too few coital contacts or timing of breeding that is either too early or too late in the cycle); third, a pseudopregnancy cycle may occur as the result of a failure to fertilize ova following coitus in which the ovulatory stimulus is adequate; and fourth, ovulation and fertilization can occur with subsequent development of fetuses.

Induction of Ovulation Without Copulation

Spontaneous ovulation occasionally occurs without male contact or intromission. Stroking of the lower back or tail head may be sufficient stimulus to induce ovulation (Lofstedt, 1982). LH surges may accompany mating in cats when mounting occurs without intromission (Concannon et al, 1980). LH release and subsequent ovulation can also be induced by artificial stimulation of the vagina and/or cervix. This can be accomplished by probing the vagina with a cotton swab, such as when obtaining vaginal cytology smears.

Ovulation can also be induced or enhanced medically. Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) can be administered at a dose of 250 IU intramuscularly on days 1 and 2 of estrus (Lein and Concannon, 1983).

PSEUDOPREGNANCY

Physiology

Basal progesterone concentrations (<0.5 ng/ml) are associated with no functioning corpora lutea. Luteal activity in pseudopregnant cats begins approximately 4 days after the first day of copulation and approximately 1 to 2 days following ovulation. Luteal function is usually defined as beginning when the plasma progesterone concentration increases above 1 ng/ml. Hormone synthesis and secretion in newly formed corpora lutea increase rapidly. Plasma progesterone concentrations are typically greater than 5 ng/ml on the third day of luteal function, and peak concentrations greater than 20 ng/ml are common by the 16th to 25th day. The progesterone concentrations then decline progressively, reaching relatively low levels by day 35 of luteal function. The mean duration of luteal activity in pseudopregnant cats was found to be 36.5 days, with a range of 30 to 50 days (Fig. 33-4; Concannon and Lein, 1983).

Behavior

The pseudopregnant cat usually ceases breeding behavior for 35 to 70 days, averaging 45 days (Concannon and Lein, 1983). The actual luteal phase lasts approximately 36 to 37 days, followed by a 7- to 10-day interestrous interval. Therefore the interval between two estrus periods is significantly prolonged in pseudopregnant cats as compared with the intervals that are not interrupted by ovulation and progesterone secretion. One might speculate that the gradual decline in plasma progesterone concentrations, which begins at about day 21 following coitus, suggests that corpus luteum function in the pseudopregnant cat is not terminated by the acute application of lytic factors but may have a lifespan predetermined at ovulation in the absence of gestational luteotrophic influences.

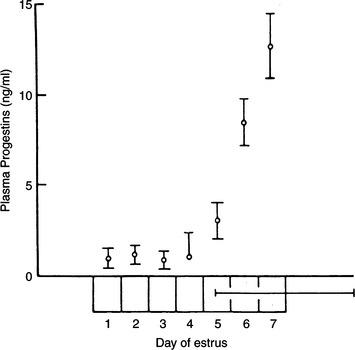

One important physiologic effect of progesterone in some species, such as the mare, sow, and ewe, is the suppression of estrus. The queen and bitch are sexually receptive despite rising progesterone concentrations. As seen in Fig. 33-5, the cat maintains sexual receptivity in spite of rising progesterone concentrations for 3 days during the average estrus.

SEXUAL BEHAVIOR IN ESTRUS

The Queen

DIFFERENTIATING “NORMAL” BEHAVIOR FROM “ESTRUS” BEHAVIOR.

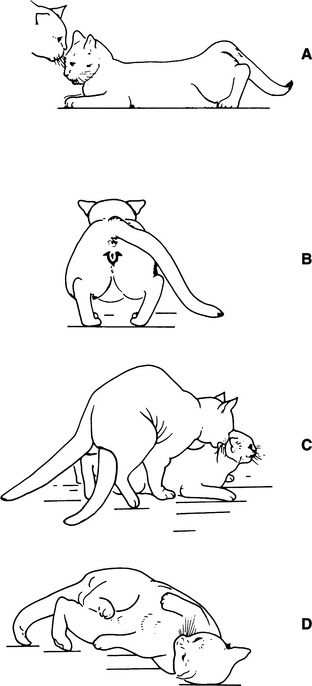

Many pet cats are quite affectionate. They enjoy human contact and commonly rub against their owners or objects in an attempt to elicit petting or to be held. Stroking along the back and rubbing at the base of the tail often results in raising of the pelvis and treading of the rear legs, even in ovariohysterectomized cats. Behavioral estrus can sometimes be recognized in normally affectionate queens only when sexual displays are out of character for that individual or when a male cat is present (Fig. 33-6). Some affectionate queens exhibit “friendly” behavior with much greater intensity and frequency when in estrus; thus their estrus periods are recognized (Voith, 1980).

BREEDING.

Female behavior.

Mating is initiated by the female. A point is reached during proestrus when the queen progresses into an “estrus posture.” This lordosis posture (with or without other possible factors) is quickly recognized by the male. The queen in estrus allows the male to grasp her neck from the side (Table 33-2; see Fig. 33-6). Once held, most females elevate the pelvis, deviate the tail, and tread with the rear legs. If this behavior is not elicited, it still may occur following mounting, the alternating stepping movements of the male’s hind feet, or the stroking of the female’s thorax by the front feet of the male. Treading of the female’s back feet may stimulate pelvic thrusting and intromission by the male, but lordosis and treading by the queen are not always seen (Voith, 1980).

TABLE 33-2 DURATION AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PREMATING, MATING, AND POSTMATING PERIODS

| Duration | Tomcat | Queen |

|---|---|---|

| Premating | Moves forward | Lordosis posture |

| (10 sec-5 min) | Sniffs female’s genitalia | Rolls |

| Circulates | Calls | |

| Calls | Treads hindlegs | |

| Moves forward | ||

| Mating | ||

| (1–3 min) | Neckbiting | Crouches |

| Mounts with forelegs | ||

| Mounts with hindlegs | ||

| Rakes with forelegs | Treads with hindlegs | |

| Treads with hindlegs | ||

| Arching of the back | ||

| (5–10 sec) | Pelvic thrusting | Bends tail to one side |

| Erection | Raises pelvis | |

| Intromission | ||

| Ejaculation | ||

| Withdraws penis | Copulation scream | |

| Turns on tomcat | ||

| Postmating | ||

| (30 sec-10 min) | Licks penis | Licks genitalia |

| Licks forepaws | Rolls | |

| Licks forepaws | ||

| Views tomcat | ||

| Re-encourages tomcat | ||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree