CHAPTER 64 Feline Bone Marrow Disorders

Bone marrow disorders have been categorized as primary bone marrow disorders and those occurring secondary to diseases of other organs or systems.1,2 Several primary bone marrow disorders of cats, including acute myelogenous leukemias, acute lymphocytic leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemias, multiple myeloma, and pure red cell aplasia (PRCA), are diagnosed routinely.3–5 However, bone marrow disorders occurring secondary to other diseases frequently are confusing both to clinicians and pathologists. Routine methods of evaluating these disorders, including single or repeated complete blood counts, serum chemistry profiles, feline leukemia virus (FeLV) and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) testing, and bone marrow aspiration, often provide only a description of the pathological condition and a list of differential diagnoses.1 When the diagnostic information is fragmented—as can occur when different people interpret the blood smear, bone marrow aspirate, and bone marrow core biopsy specimen or when the clinician and pathologist(s) fail to communicate—the problem is compounded. However, with a careful evaluation of the case history and a coordinated evaluation of the blood smear, bone marrow aspiration smear, and bone marrow core biopsy specimen, the clinician frequently can make an etiopathological diagnosis.

In this chapter, I will begin with a discussion of general lesions in bone marrow that need to be understood both by the pathologist interpreting bone marrow specimens and the clinician applying the results to a particular case. Thereafter, I will discuss specific bone marrow disorders occurring in cats, including the clinical, hematological, and bone marrow features needed to achieve an etiopathological diagnosis. An overall diagnostic approach for evaluation of hematological disorders in cats has been presented elsewhere.1 The diagnostic plan for evaluation of hematological disorders should be conducted in several phases. The initial phase should include results of a complete history (including exposure to drugs and toxins), physical examination, complete blood count, and blood smear examination. Thereafter, infectious diseases (FeLV, FIV, Mycoplasma spp., parvovirus) and immune-mediated diseases should be evaluated with appropriate diagnostic tests. Because mild to moderate nonregenerative anemias frequently occur secondary to inflammatory, renal, hepatic, neoplastic, or certain endocrine disorders, a serum chemistry profile and other appropriate diagnostic tests to detect these conditions are indicated. If the initial phase of testing does not achieve an etiological diagnosis, a bone marrow aspiration and core biopsy are indicated. Both the aspirate and core are essential for complete evaluation of bone marrow disorders. Although bone marrow differential cell counts are performed infrequently, they can be useful, and determining the percentage of myeloblasts in the aspiration smear is recommended. In selected cases, additional testing may be needed. These tests include immunophenotyping of leukemias, determination of clonality, and FeLV testing on the bone marrow aspirate.

HISTOPATHOLOGICAL ALTERATIONS IN BONE MARROW

Several histopathological changes are seen frequently in feline bone marrow and contribute to bone marrow failure.6–9 Although these changes can be associated with several disease conditions, they can be used to identify the general type of marrow injury and to focus the search for an etiological diagnosis. A core biopsy specimen is needed to identify these lesions. These pathological changes generally are subclassified as acute or chronic bone marrow injury.6,10 Lesions associated with acute marrow injury include myelonecrosis and acute inflammation, and lesions associated with chronic marrow injury include chronic inflammation, myelofibrosis, and osteosclerosis. These conditions may occur concurrently and usually are described and defined by which process is the most prominent. All of these conditions occur secondary to other disease processes. Therefore the goal should be to identify and treat the underlying condition. If the primary condition is treated successfully, the bone marrow failure usually resolves.

ACUTE MARROW INJURY

Myelonecrosis

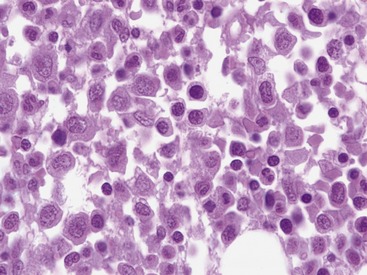

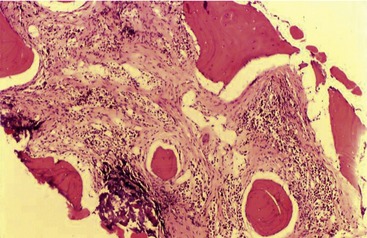

Myelonecrosis is thought to result from ischemic injury to marrow.11 Necrosis can be associated with toxic injury to marrow sinusoids associated with sepsis or with immune-mediated injury or ischemia associated with thrombosis such as in disseminated intravascular coagulation or marrow neoplasia.8,11 Myelonecrosis can appear as multifocal areas of coagulation-type necrosis or as individual cell necrosis.8,11,12 Coagulation-type necrosis is rare in cats.11 Individual cell necrosis, a frequent finding in cat bone marrow, is characterized by large numbers of degenerating, frequently anuclear cells and increased pink amorphous background material (Figure 64-1).11 The most frequent causes of bone marrow necrosis are immune-mediated hemolytic anemia (IMHA) (see Chapter 60) and sepsis.11,13 Other causes include myelodysplastic syndromes, myeloproliferative diseases, and chronic kidney disease. Therefore identifying significant necrosis in the absence of evidence of a myelodysplastic syndrome or myeloproliferative disease in marrow should prompt a search for IMHA or sepsis. IMHA frequently is accompanied by lymphocytosis in bone marrow, further helping to identify an immune etiology.

ACUTE INFLAMMATORY INJURY

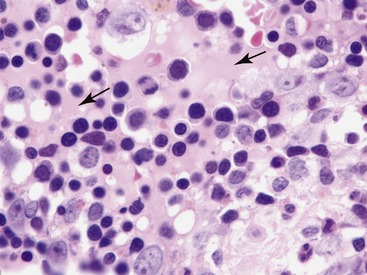

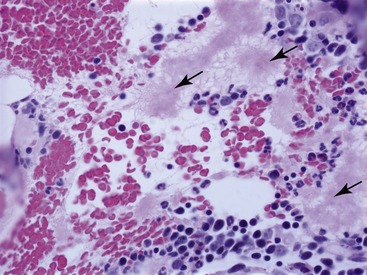

Acute marrow inflammation results from injury to bone marrow sinusoids resulting in altered permeability.9,13,14 Histopathological changes associated with altered vascular permeability include sinusoidal dilation or congestion, interstitial edema, or hemorrhage.9,13 Interstitial edema is seen as amorphous pink homogeneous material between hematopoietic cells (Figure 64-2).13 Vascular injury also can result in exudation characterized by multifocal fibrin deposits or multifocal infiltrates of neutrophils.13,14 Fibrin appears as pink fibrillar material that can be identified on hematoxylin-eosin–stained sections, but it stains selectively with Frazier-Lundrum stain (Figure 64-3).9 These fibrin deposits frequently contain variable numbers of segmented neutrophils.13,15 Causes of acute inflammation in feline bone marrow include IMHA and infectious diseases including bacterial sepsis, parvovirus infection, and feline infectious peritonitis (FIP).8,9,13,16,17 Fibrin is particularly prominent in cats with FIP.8 Therefore identifying acute inflammation in marrow should prompt a search for these conditions.

CHRONIC BONE MARROW INJURY

Chronic bone marrow injury can occur as a chronic manifestation of acute marrow injury or arise independently.8,13 Bone marrow cellularity is variable but typically is decreased. Chronic injury frequently is accompanied by myelofibrosis.13

Chronic Inflammation

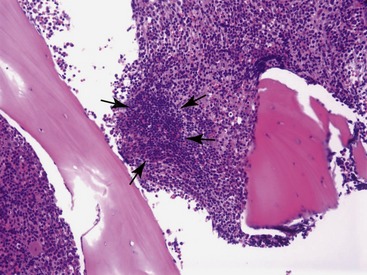

Types of chronic inflammation observed in cats include lymphocytosis and plasma cell hyperplasia.3,13,18 Lymphocytosis is the most frequent type of chronic inflammation.13,18 In a retrospective study of 203 clinical bone marrow reports from cats, lymphocytosis (i.e., lymphocytes >15 per cent of all nucleated cells) was observed in 15.6 per cent of the specimens.6 In some cats, lymphocyte numbers exceeded 50 per cent of all nucleated cells in the bone marrow.6,13,18 More than 80 per cent of cats with lymphocytosis have a diagnosis of nonregenerative IMHA.18 Other, less frequent, causes of bone marrow lymphocytosis include cholangiohepatitis and idiopathic reactive lymphadenopathy.13,18 Differentiating benign lymphocytosis from chronic lymphocytic leukemia can be problematic. The age of the affected cat should be considered. Whereas many conditions that induce benign lymphocytosis, including IMHA (see Chapter 60), PRCA, and idiopathic reactive lymphadenopathy, are conditions of young cats, chronic lymphocytic leukemia is a disease of old cats.18 Lymphocyte morphology and distribution also provide some clues. In chronic lymphocytic leukemia, lymphocytes frequently are mildly pleomorphic and have cleaved or lobulated nuclei.18 Benign lymphocytes frequently are arranged in small, multifocal aggregates in bone marrow, whereas they are distributed diffusely in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (Figure 64-4).18 Furthermore, the number of lymphocytes in blood helps differentiate benign lymphocytosis from chronic lymphocytic leukemia.18,19 More than 25,000 lymphocytes/µL in blood is suggestive of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, while more than 50,000 lymphocytes/µL usually is diagnostic for chronic lymphocytic leukemia.19,20 Additionally, immunophenotyping of lymphocytes in bone marrow may be useful. Benign lymphocytes in bone marrow are mostly B cells, whereas malignant lymphocytes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia usually are T cells.18,19

Because plasma cells are distributed unevenly in bone marrow, plasmacytosis usually is evaluated subjectively in bone marrow aspirates or core biopsy specimens.12 Plasmacytosis has been observed in 6 per cent of feline bone marrow specimens.6 Plasmacytosis in cats has been associated with IMHA, PRCA, immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, and FIP.

Myelofibrosis and Osteosclerosis

Myelofibrosis is a frequent finding in feline bone marrow and is characterized by the presence of fibroblasts or by deposition of collagen or reticulin fibers (Figure 64-5).6,21 Special stains are needed to detect reticulin fibrosis (e.g., Gomori’s stain).15 Reticulin fibrosis is present in the majority of cats with acute myelogenous leukemia.21 Extensive reticulin fibrosis may interfere with obtaining a bone marrow aspirate, resulting in a “dry tap” even when the marrow is hypercellular.21 Other conditions associated with myelofibrosis include nonspecific myelonecrosis, nonregenerative IMHA, myelodysplastic syndromes, chronic kidney disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and FIP.8 Rare cases of idiopathic myelofibrosis, a rare form of chronic myeloproliferative disease, have been reported in cats.22

Cats with myelofibrosis typically have a severe nonregenerative anemia.8 Leukopenia and thrombocytopenia are less frequent findings. Ovalocytes and other erythrocyte shape changes are seen rarely in cats. The prognosis for secondary myelofibrosis varies with the primary condition.8 Cats with myelofibrosis secondary to IMHA or idiopathic myelonecrosis frequently recover, and the fibrosis resolves with successful treatment of the primary condition.8 Alternatively, myelofibrosis associated with myeloproliferative disease, myelodysplastic syndromes, FIP, and chronic kidney disease tends to be progressive presumably because the initiating factors persist. Therefore the prognosis for myelofibrosis should be based on the primary disease condition, the severity of the anemia present, and the degree of hypocellularity of the bone marrow.8

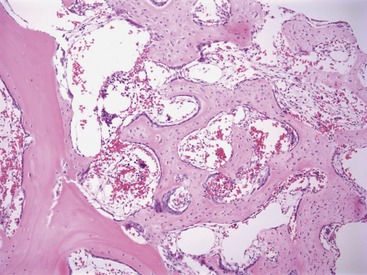

Osteosclerosis (also termed myelosclerosis) is a condition in which the marrow cavity is reduced in size or obliterated as a result of bony proliferation (Figure 64-6). When severe, the associated thickening of bone is visible radiographically.22 This type of severe osteosclerosis has been associated with FeLV infection.23,24 Mild osteosclerosis frequently is associated with cases of severe myelofibrosis. These changes are seen in core biopsy sections as thickened trabeculae with irregular edges that contain increased numbers of osteoblasts.

SPECIFIC BONE MARROW DISORDERS

HEMATOLOGICAL DISORDERS ASSOCIATED WITH INFLAMMATION AND NEOPLASIA

Inflammatory diseases are accompanied consistently by a mild to moderate normocytic normochromic nonregenerative anemia.25,26 This appears to be the most frequent cause of anemia in cats.25 The hematocrit drops within the first few days after onset of inflammation and then stabilizes.25,26 The pathogenesis is complex. At least three factors have been implicated, including impaired bone marrow response to anemia, iron sequestration in macrophages making it unavailable for erythrocyte production, and shortened erythrocyte lifespan.25 Proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1, play a prominent role in the anemia. Tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1 induce ferritin synthesis (the major protein involved in iron sequestration), inhibit proliferation and differentiation of erythroid progenitor cells in bone marrow, reduce formation of erythropoietin, and reduce responsiveness of erythroid precursor cells to erythropoietin. More recent studies incriminate hepcidin, an acute phase protein that regulates iron metabolism, as a mediator of the anemia of inflammatory disease (AID).27 Diagnosis of AID is based on identifying a mild to moderate normocytic normochromic nonregenerative anemia and detecting an underlying inflammatory disease process. Bone marrow usually is essentially normal. However, marrow may be hypercellular with an increased myeloid-to-erythroid ratio due to myeloid hyperplasia in response to chronic inflammation. Differentiating AID from iron deficiency can be problematic. Both conditions are characterized by low serum iron; however, cats with AID typically have high serum ferritin levels, whereas cats with iron deficiency have low serum ferritin levels.26,28 Other differentiating characteristics frequently associated with iron deficiency include microcytosis or hypochromasia and increased platelet count.29 In dogs, absence of hemosiderin in bone marrow is a reliable indicator of iron deficiency; however, healthy cats lack stainable iron in bone marrow.29 Unlike AID, iron deficiency appears to be a rare condition in adult cats, occurring mostly in kittens as a result of blood loss.29

Hematological alterations accompany large or metastatic malignancy consistently. Disseminated malignancy is accompanied almost invariably by AID, resulting in a mild to moderate normocytic normochromic nonregenerative anemia.30,31 Acute or chronic blood loss also accompanies disseminated or metastatic malignancy frequently. Chronic external blood loss can cause iron deficiency, which impairs erythropoiesis and results in a microcytic or hypochromic anemia. However, as mentioned previously, iron deficiency occurs rarely in adult cats.29

Increased numbers of normal or atypical nucleated erythroid cells or leukocytes have been observed in the blood or bone marrow of cats with neoplastic processes.30,31 This condition has been termed leukoerythroblastic anemia or megaloblastic anemia.30,31 However, the author prefers to use the general term secondary dysmyelopoiesis for this condition. Secondary dysmyelopoiesis is defined as nonclonal dysplastic changes in blood or bone marrow that occur secondary to other disease processes, drug treatments, or toxin exposure.32

Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia also can contribute to anemia associated with neoplasia.30,31 Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia results from direct traumatic damage to erythrocyte membranes. It can result from damage to vascular endothelium or from fibrin deposition within blood vessels. Fibrin deposits within blood vessels are common in disseminated intravascular coagulation (see Chapter 62). The hallmark of this process is the presence of schistocytes and keratocytes in the blood of affected cats. Other, less frequent, causes of hematological disorders associated with neoplasia include secondary immune-mediated hemolytic anemia and hemophagocytic syndrome.30,31

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree