Chapter 12 Fears, phobias, and anxiety disorders

Introduction

Take a look at the wide array of behavior problems that are problematic for pets and their families and you will notice that fear and anxiety play major roles or contribute in some way to a majority of canine and feline behavior disorders (see definitions of anxiety, fear, and phobia in Box 12.1). Storm phobias, noise phobias, social avoidance, fear-related aggression, compulsive disorders, and submissive urination have obvious anxiety components, but even problems such as urine marking, territorial aggression, and resource guarding can be fueled by fear or anxiety. Understanding the behavioral and physiologic aspects of anxiety and the fear response, as well as how to choose and coach the owner patiently through conditioning exercises become important aspects of working with a wide variety of behavior problems.

The fear response

When an animal experiences anxiety, fear, or stress, both the sympathetic system and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis are stimulated so that the body can respond to the threat.1 The sympathetic system releases norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and epinephrine (adrenaline) from the subcortical areas of the brain and adrenal gland, leading to the behavioral responses of fight, flight, or freeze. The physiologic response is an almost instantaneous immediate increase in heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and vasoconstriction to internal organs. Epinephrine also stimulates breakdown of glycogen and fat (lipolysis) and increases glucose production (gluconeogenesis) to provide immediate energy to fuel fight or flight. Stimulation of the HPA axis provides cortisol release which aids in the immediate response; however, chronic stimulation may lead to the medical and behavioral consequences associated with chronic stress (see Chapter 6). Studies have shown that psychological factors may stimulate the HPA axis more than physical factors; therefore, addressing mental well-being is essential to both health and welfare.2,3

The amygdala is an almond-shaped structure located deep within the temporal cortex; it is considered part of the limbic system. The amygdala is considered to be the primary site responsible for processing external and internal triggers that are fear-evoking or potentially threatening to the animal (i.e., visual, auditory, odor, hypoxia, pain). Inputs run from the sensory organs through the thalamus.4 When an animal perceives the stimulus, the amygdala triggers an immediate physiologic fear or startle response, priming the body for immediate action. A second slower pathway travels through the cortex to analyze the signal to determine if the threat is real but once the emotional stage is triggered it may be difficult to inhibit. The amygdala signals the cells of the paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus to release corticotropin-releasing factor, thus stimulating the hypothalamic–pituitary axis and the release of norepinephrine from the locus ceruleus.5 The amygdala is also the central site for fear conditioning; it integrates prior learning and memory to stimulate other brain centers to initiate the autonomic threat response.6 In humans, fear conditioning is thought to play a role in the development of anxiety disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder, phobias, and panic disorder.

The locus ceruleus is a brainstem nucleus located in the gray matter of the pons.7 The locus ceruleus contains the highest concentration of norepinephrine neurons in the brain and sends projections to many brain regions, including the cortex, hypothalamus, hippocampus, and the median and dorsal raphe nuclei.8 Stimulation of the locus ceruleus triggers the release of norepinephrine. Inputs to the locus ceruleus arrive via sensory and visceral stimuli and from afferent projections from the central nucleus of the amygdala. Corticocotropin-releasing factor resulting from amygdalar stimulation has an excitatory effect on the locus ceruleus.9 Dysregulation of the locus ceruleus may be associated with a variety of psychiatric disorders, including panic attacks, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, sleep and arousal disorders, and affective disorders.

The hippocampus is another major nucleus of the limbic system and is involved in memory storage.10 It has anatomical connections with the amygdala and hypothalamus. It is also considered to be responsible for processing contextual information, and differentiating between safe and dangerous; dysfunction may lead to an anxiety response to benign stimulation with an overestimation of potentially threatening context, as in posttraumatic stress disorder in humans.11 The hippocampus can normally suppress the HPA axis. However, chronic stress and cortisol can damage the hippocampus which can then no longer regulate the HPA axis, resulting in excessively high levels of cortisol.5 A reduction in hippocampal volume has been identified in posttraumatic stress disorders and in animals exposed to chronic stress.12 The individual is thought to be less able to draw on memory to evaluate the nature of the stressor when hippocampal function is compromised.

The dorsal and medial raphe nuclei are two functional neuron clusters located in the centromedial portion of the brainstem and considered part of the reticular formation.13 Together these nuclei provide virtually all serotonin input to the forebrain.14 It is hypothesized that the limbic projections of the medial raphe nucleus help modulate fear and anxiety, including autonomic responses, while the dorsal raphe nucleus modulates cognitive and motor components that inhibit flight or fight responses.14

Excessive fear responses may be due to genetic factors, inadequate early environmental experiences, inadequate early socialization, a conditioned fear due to one or more unpleasant experiences, medical or behavioral pathology, or a combination of these factors (Box 12.2). Many fearful behaviors can be linked to experiences in the first year of development. Handling, nutritional and maternal care during the first few weeks of life in the breeder’s environment, as well as exposure during the socialization period with its own and other species and to its environment can set the pet up for success or can contribute to fearful behaviors that might be difficult, if not impossible, to resolve. However, even with adequate exposure, fear may arise unless exposure to social and environmental experiences is maintained.15 There may be a second phase of heightened sensitivity arising around sexual maturity.16,17 Unpleasant and stressful experiences during early adolescence, including punishment-based training, may also contribute to fear conditioning and increased avoidance.18–24 Attendance at puppy classes and use of pheromones may to some degree be preventive.25–27

Box 12.2

The nature of fear1

| Determinants of fear | |

| Genetics | |

| Environmental | |

| Components of fear | |

| Physiology | |

| Behavior | |

| Emotion | |

When dogs and cats are exposed to new stimuli, their response will depend in part on their sociability (genetics, stage of development), previous experience with similar stimuli, and the emotional and medical health of the pet at the time of exposure.2 If the outcome is positive then the fear may reduce with further exposure. If the stimulus has no consequence, the pet may ignore the stimulus with further exposure. However, pets that have an unpleasant experience, or perceive that the stimulus might be harmful, will avoid or become increasingly fearful of the stimulus. Increasing the frequency of exposure to fear-evoking stimuli has been shown to increase the risk of inducing further fear and phobias.28 An intensely unpleasant or aversive event can lead to an intensely fearful and lasting memory of the stimulus (one-event learning). Although the pet may only become fearful of specific stimuli (discrimination) such as a noise (e.g., gunfire), place (e.g., veterinary clinic), or person (e.g., neighbor’s child), some pets may generalize to many similar stimuli (e.g., all children). In addition, the pet may become fearful of events that precede the unpleasant situation (e.g., the car ride that precedes the veterinary visit). High states of arousal or anxiety place the dog in a state of hypervigilance, where fear responses are automatic, and preclude the possibility of conscious decisions as to how to respond (Box 12.3). Therefore, only if the pet’s level of arousal is sufficiently reduced can it review options and make conscious decisions as to whether a stimulus is positive, aversive, or of no consequence. Arousal can be reduced by ensuring that the pet is calm through training by using products for control such as head halters, by selecting an appropriate environment for exposure, and through selection and control of appropriate stimuli for retraining. Drug therapy may also be useful.

Box 12.3

Signs of anxiety

• Increased motor activity (restlessness, pacing, circling)

• Displacement behaviors – out-of-context grooming and scratching, yawning, lip licking, whining and barking, destructive, digging

• Changes in social soliciting behavior – increase or decrease in attention seeking

• Physiologic signs (trembling, dilated pupils, hypersalivation, ↑ respiratory rate, ↑ heart rate, urination, defecation, vomiting)

For signs of fear and anxiety see chapter 2 and Appendix B: Commmunication – Fear and Body Languae Resources.

Regardless of the cause, each fear-eliciting event that does not end with a positive outcome is likely to aggravate the problem further.28 Since the goal of counterconditioning is to change the association with the stimulus to one that is positive, any response from the owner or the stimulus that might lead to a negative or unpleasant consequence will further increase the fear and anxiety. Therefore punishment and other aversive correction techniques must be entirely avoided, and the stimuli should be muted, minimized, or avoided until controlled and successful exposure training can be implemented. In addition, if the owner displays any emotions of anger or anxiety, this is likely to increase the pet’s anxiety. Also, if the pet escapes from the situation or aggression results in retreat of the stimulus, then the behavior has been negatively reinforced because the threatening stimulus has been removed. In treating a fear-related problem, it is often just as important to tell the family what not to do, as it is to tell them what to do.

Basic behavioral modification and the fearful pet

Techniques for managing fears and phobias include controlled exposure, habituation, systematic desensitization, counterconditioning, shaping, response substitution, and positive reinforcement29–33 (see Chapter 7). They can be used individually or together in behavioral modification therapy (Table 12.1). If a situation arises during training or counterconditioning that might trigger an aggressive response, safety is the overriding concern. The use of confinement, tie-down, muzzle, and the physical control provided by a leash and head halter (dogs) or leash and harness (cats) can prevent aggression and retreat.

Table 12.1 Behavioral modification techniques used for fearful behaviors

Desensitization, counterconditioning, and controlled exposure

If the fear is mild and the owner has good control over the pet, stimulus, and situation, controlled flooding techniques (continuous exposure to stimuli at levels that are minimally above the threshold that elicits fear) may be successful as long as the pet will quickly habituate to the stimulus so that a reward can be given. Ideally, this would be a valued positive reinforcer. However, removing the pet from the situation or removing the stimulus before the pet begins to calm may negatively reinforce the behavior. If the stimulus is too intense for the pet to calm quickly, the stimulus intensity should be reduced (by increasing the distance between the pet and the stimulus) to minimize the fear to a level at which the pet can habituate. A leash and head halter can be helpful in providing increased control and ensuring compliance. Once all signs of fear subside and the pet responds to the owner’s commands, rewards (food, play, social attention) should be given. The strength of the stimulus can gradually be increased during each succeeding training session as long as the endpoint of each exposure is positive (Box 12.4).

Box 12.4

Behavior modification for dogs with fear and phobias toward noises and locations (client handout #8, printable version available online)

Steps for treating a pet that is fearful of inanimate objects and sounds

1. Know the signs of fear: Identify all stimuli and situations that cause the pet to be fearful. Remember that multiple stimuli may add to the fearful response so that each stimulus should be identified separately. For example, a pet that is fearful of a vacuum cleaner might be afraid of the sound, sight, or motion of the vacuum cleaner. Pets fearful of thunder may also react to the rain, lightning, darkness, barometric pressure or electric charges.

2. Prevent your dog from experiencing the stimuli except during counterconditioning. This may be difficult for certain phobias such as thunderstorms so that medication or other products might be needed to help calm your pet or reduce exposure to the stimuli. Confinement to an area where sounds or sight of the stimuli can be avoided, using music or white noise to mask external sounds, calming caps or goggles that reduce visual stimuli, ear bands or muffs that reduce audible stimuli or calming shirts or wraps, might aid in reducing the level to one that is tolerable for the dog.

3. Train the dog to relax or settle on command, in the absence of any fear-evoking stimuli (see Box 7.2, client handout #23, for training dogs to settle, and client handout #13 on structured interactive training, C.14, available online). Begin in an environment where the dog is calm, focused, and has minimal distractions. Gradually proceed to progressively more distracting locations and situations. The initial conditioning should be done by family members with whom the pet is calmest, most controlled, and responsive. For some dogs, using a head halter improves the speed and safety of training. Implementing a program of predictable interactions where all affection and social rewards are only given for calm and focused behaviors helps to reduce anxiety both by giving the pet control over its rewards and by ensuring that only calm behaviors get rewarded. Practice the training in a variety of environments using treats or toys as rewards. Consider clicker training to be able to immediately reward and gradually shape more relaxed responses when at a distance from your pet.

4. For storm and firework phobias, it can be particularly useful to train the pet to settle or go to a location where it feels comfortable and secure, and where the auditory and visual stimuli can be minimized, such as a crate with a blanket or cardboard appliance box as cover. In addition, positive cues can be implemented that further calm and distract the dog. This can be accomplished by pairing a CD, video, white noise, or even a towel or blanket that has the owner’s scent with each positive settle training session. Encourage the dog to enter voluntarily by placing its favored chews and food-filled toys in the area.

5. Each stimulus that leads to fear must be identified and placed along a gradient from mildest to strongest. It will be necessary to reproduce the stimuli so that they can be muted or minimized and presented in a controlled manner. An audio recording or video might be a good starting point for conditioning to the sound of the stimulus. If a pet is afraid of the sound, sight, and movement of the vacuum cleaner, then these may all need to be controlled and introduced separately.

6. Determine the pet’s favored rewards and save these for retraining and counterconditioning. For some pets, food is the strongest reward while others may be more responsive to a favored play toy. The reward should be presented each time the pet settles in response to the stimulus. Always train with a quiet, relaxed, upbeat tone of voice.

7. If the pet responds fearfully as you proceed slowly through more intense stimuli, stop the exposure, wait till the pet is fully calm and reward. The stimulus can then be reintroduced at a slightly lower level, and desensitization and counterconditioning can resume.

8. Once each stimulus has been presented along a gradient of increasingly stronger stimuli and the pet acts calmly and takes rewards in the presence of each stimulus, the separate elements can then be combined and gradually introduced as a group (e.g., vacuum turned on and moving).

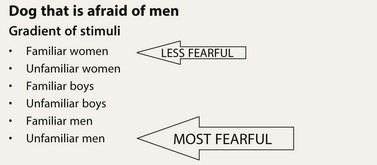

Fear of people

Some pets show fear toward a particular person, all unfamiliar people, or a type of person (child, baby, man in uniform – Box 12.5). Depending on how a pet was socialized when it was young and the experiences it has had with people, it may be fearful of individuals with whom it is unfamiliar or with those it associates with an aversive experience.

Management and treatment

For each type of person, the owner should develop a gradient or hierarchy of intensity from weakest to strongest. Controlling the appearance or presentation of the fear-eliciting person and the distance between the person and the pet are two means of developing this gradient (Boxes 12.4–12.6). The conditioning should take place in a calm, nonthreatening environment where the pet can easily be controlled. For some pets, it might be helpful to hold the first session on neutral territory such as at the neighborhood park. The goal is to associate the person with something that is highly valued such as a favored treat, toy, or social attention (counterconditioning). The key to success is to determine the threshold for eliciting fear of the stimulus (e.g., the distance where the pet exhibits the slightest fear) and then begin conditioning below the threshold. Eventually, the appearance of the person becomes a cue that something good will happen. A leash and head halter for dogs or a crate for cats might be used for exposure if there is the potential for aggression and to prevent escape.

At first, the strangers should ignore the pet while the owner gives treats for relaxed behavior at a safe distance. Initially, eye contact should be avoided. The owner and the pet can slowly approach the person as long as no fear is evoked and the pet is given a tasty treat every few steps. Next, the treats can be tossed by the stranger. Fearful dogs may cower and retreat but some may attack. Therefore the owner should proceed cautiously and slowly to ensure safe and successful retraining. A head halter can provide safe and effective control for dogs while a carrying cage or a body harness and leash can help to ensure control and safety for cats. Perhaps most important is to have reasonable goals. If the pet is intensely fearful or has the potential for aggression, interactions, especially with children or the elderly, may need to be limited (Box 12.7) or entirely avoided.

Box 12.7

Example of a hierarchy or gradient for desensitization of a dog fearful of men in uniforms

If the dog enjoys physical contact from known individuals and the owner can evaluate the situation and determine that the dog is relaxed and willing to engage in further interaction, the owners should proceed to structured interactions with the visitors (see Appendix C, form C.14, client handout #13, printable version available online). Visitors are told that they may not touch the pet unless it first sits and takes a treat. This does several things to help make the situation safe. If, for some reason, the pet shows signs of fear and is too anxious to eat, the interaction should not yet progress to physical interaction. By giving a command that the dog has learned will consistently receive rewards, the dog controls the outcome; therefore if it does not sit and settle, it is indicating that it is not comfortable with taking the reward from the stranger. When the dog does take the treat from the visitor, it is building a positive relationship with the stranger (Boxes 12.8 and 12.9).

Box 12.8

Behavior modification for dogs that are afraid of people or pets (client handout #9, printable version available online)

Steps for treating a pet that is afraid of animate stimuli (people, other animals)

1. Know the signs of fear; identify all stimuli and situations that cause fear (e.g., children playing, tall men).

2. Prevent your dog from experiencing the stimuli except during conditioning sessions.

3. If there is aggression associated with the fear, then your dog should be trained to wear a head halter or basket muzzle so that safety during exposure exercises can be ensured.

4. Train the dog to relax on cue in the absence of any fear-evoking stimuli. Work on the cues you plan to use when you begin exposure. Outdoors, you might focus on walking with a short amount of slack leash (“heel”), sit and focus and turn and walk in the other direction (“walk away”). Indoors, “sit” and “focus,” “down” and “settle” or crate and mat exercises might be most useful. A head halter can be used to ensure success.

5. Once the dog will reliably focus, settle, and accept rewards in a variety of environments, then training can progress to include exposure to controlled levels of the stimulus.

6. Set the pet up to succeed. A familiar dog or person can be used as the initial training stimulus to ensure that your dog will relax and take rewards as soon as it sees the stimulus (e.g., dogs on the street, visitors at the door).

7. For both counterconditioning and response substitution, the dog’s favored rewards should be used. Save the rewards of highest value for training sessions and exposure to the stimuli.

8. You will need to develop a gradient for introduction to the fear-evoking stimulus so that initial exposures are mild. Setting up sessions with good stimulus control can be difficult and take some forethought but is essential for successful counterconditioning and response substitution.

Box 12.9

Desensitization and counterconditioning for cats that are afraid of people or other cats (client handout #10, printable version available online)

Fear of people and pets – desensitization and counterconditioning – common first steps

• Begin with safe and effective control of both your cat as well as the stimulus that causes fear. Initially the cat and the stimulus (other cat, people) can be separated by confinement behind a common solid door (until the cat adapts to the odor and sounds of the stimulus) or across a glass or screen door, which would allow for safe visual exposure. A positive association can be achieved (countercondition) by giving the pet favored rewards with each exposure.

• The next step is gradually to increase the intensity of exposure while ensuring the cat continues to take rewards. If barriers have been used, the goal is gradually to get the cat into the same room with the stimulus (person, pet) at sufficient distance that the cat will take the food or treat.

• If the cat exhibits fear at any step in the desensitization program, go back to the step that was successful and repeat until the pet will readily take rewards before progressing again. Always end on a positive note. It is critical that the owner and the stimulus at all times remain calm and show no fear and that the owner uses no punishment as these will increase fear and anxiety.

Fear of people and other animals

1. Know the signs of fear and identify the fear-eliciting triggers. For some cats, fear may be generalized so that all strangers or other animals cause fear. Other cats may be afraid of specific people or pets. Until prepared to move forward with conditioning exercises, avoid all fear-evoking stimuli.

2. Setting up safe exposure: because a fearful cat can quickly become aggressive, precautions must be taken before beginning treatment. Some method of safe exposure will need to be devised. Initial exposure to stimuli should be sufficiently mild and gradual that no fear is exhibited. A good starting point is to have the cat adapt to the sounds and smell of a visitor by giving the cat rewards while housed in an adjacent room. Videos or audio tapes might be useful for introducing the sound of a stimulus at low intensity. If the cat becomes anxious and cannot be called away with a command and reward, a large blanket or towel can be wrapped around the cat to move it into another room until it calms.

3. Each stimulus will need to be presented along a gradient beginning with exposures to the stimulus that do not cause fear, and moving slowly to higher intensities with each positive outcome. To develop a gradient you will need to determine how to control the stimuli that cause fear (situations, people, places, or animals) so that they can be gradually intensified for counterconditioning. If the cat is fearful of a particular person or type of person (e.g., child), the training can begin with milder stimuli, such as a calm adult or teen. The stimulus intensity is then gradually increased. The person may move slightly closer during training sessions, but should not move closer until the cat takes the reward and is calm. Next, the goal will be for the person to give or offer the reward to the cat, or to throw it near the cat so that it approaches to take the reward. Each step should end on a positive note, with the cat receiving a reward before proceeding to the next level. Withhold rewards except when the stimulus is present.

4. Control can be provided with a leash and harness, keeping the cat in a crate or carrier, or by closing doors to block escape (provided the cat does not become aggressive or more fearful). The cat should be positively conditioned to accept any new control device prior to exposure.

5. Food or treats that have the highest appeal should be identified and saved exclusively for desensitization, counterconditioning, and reward training. Favored toys, catnip, and even short periods of affection may also be effective for counterconditioning if these are important to the cat and reserved for the exposure sessions.

6. Training the cat to respond to verbal cues such as “sit,” “come,” or “go to a place” before every reward is given may provide a useful, predictable pattern of interaction. Cats may also be taught tricks.

7. If the cat is too reactive or anxious to learn new behaviors then medication or pheromones may reduce anxiety and promote positive learning.

Treatment – fear of other cats: desensitization and counterconditioning

1. Introduction of a new cat into the household or reintroducing a cat in the home to one that it fears must be done slowly and cautiously so that each association has a positive outcome.

2. Once the cats have been adapted to each other across a common doorway, there must be a safe means of control so that the cats can be put in a common area. It may be helpful initially to place a towel with the cat’s scent in the other cat’s confinement area for a week before beginning visual exposure. Another approach is to allow one cat out into the common area while the other remains housed in its own room and to alternate for a few days so that they are each familiar with the common area. Also add as much space for perching, climbing, and hiding as is practical, and maintain separate litter stations to reduce conflict. It may also be helpful to offer a collar-activated cat door so that each cat can learn to go back into its own room without the other cat following.

3. When placing the cats together maintain sufficient distance that they show no fear and will take treats, catnip, or play toys when together. A body harness on one or both cats or crates for one or both cats may be useful when first introducing them to a common area together.

4. At this point, if both cats have been in crates, the more fearful cat may be allowed out, and the food, treats, toys, or catnip should be given progressively closer to the other cat’s crate. When both cats can be placed out of the crates in the same room together while eating at a sufficient distance to avoid fear, a leash and harness on one or both cats may be necessary for safe control. If one or both cats do not eat, move the food bowls farther apart. If things go well, the dishes can be moved slightly closer together during subsequent conditioning sessions.

5. Progress slowly! Allowing either cat to become fearful or aggressive sets the program back. The cats must remain separated except during counterconditioning sessions.

6. When the cats appear ready for some freedom to roam the home, it might help to place a bell on the assertive cat to help the family supervise and so the other cat knows when it is near.

7. Drugs and pheromones (e.g., Feliway) may be useful during a behavior modification program to reduce apprehension and allow the cat to learn pleasant associations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree