Chapter 6 Farm Animal Anesthesia

Sedation of Farm Animals

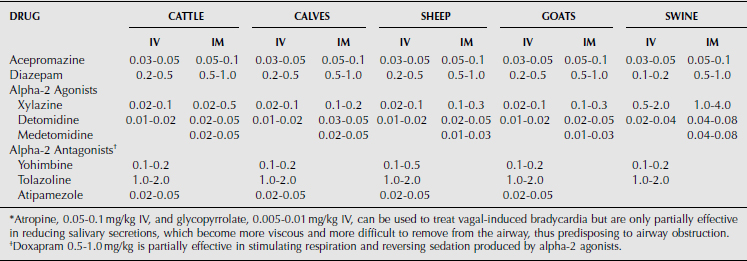

Xylazine, acepromazine, diazepam, pentobarbital, butorphanol, and chloral hydrate are used as preanesthetic medications and sedatives in farm animals (Table 6-1). Xylazine and detomidine are alpha-2 agonists that act on the central nervous system alpha-2 adrenoreceptors to cause sedation, analgesia, and muscle relaxation. Higher doses of xylazine and detomidine induce recumbency and profound CNS and respiratory depression. The amount of drug required to produce sedation depends on an animal’s temperament and excitement at the time of administration. Excited animals cannot be sedated with standard drug dosages. In general, a xylazine dose one-tenth that needed to sedate horses is required to sedate cattle. A low concentration of xylazine (20 mg/mL vs. 100 mg/mL) is recommended to avoid overdosage because of farm animals’ sensitivity to the drug. Intravenous or intramuscular doses of xylazine (0.015 to 0.025 mg/kg) will sedate cattle without inducing re-cumbency. Higher doses of xylazine (0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg) induce recumbency and light anesthesia. Sedation is a common side effect after epidural administration of xylazine (see Local Anesthetic Techniques).

Xylazine sedation, analgesia, cardiopulmonary depression, and muscle relaxation are reversible (see Table 6-1). Tolazoline and yohimbine often are used to reverse sedation and cardiopulmonary depression. Tolazoline seems to have a faster onset of action than yohimbine. Adverse side effects include hypertension and cardiac arrhythmias. The recommended dose for yohimbine is 0.12 mg/kg IV in cattle, with higher doses required for small ruminants (up to 1 mg/kg IV). The recommended dose of tolazoline for ruminants is 0.5 to 2.0 mg/kg IV, and fewer instances of adverse effects occur than with yohimbine.

Acepromazine is a phenothiazine tranquilizer commonly used in horses but infrequently in cattle because of its long duration of action and withdrawal times. The acepromazine dose for cattle is 0.03 to 0.05 mg/kg IV; for sheep and goats it is 0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg IV. Intramuscular injection is extremely painful, and absorption is variable. Injection into the tail vein should be avoided because accidental intraarterial injection can cause sloughing of the tail as a result of arterial vasospasm and ischemic necrosis. Acepromazine may also increase the risk of phimosis in breeding males and predisposes adult cattle to regurgitation during anesthesia. In swine, acepromazine helps reduce the risk of hyperthermia and porcine stress syndrome. The dose of acepromazine to tranquilize swine is 0.5 mg/kg IM.

Local and Regional Anesthetic Techniques

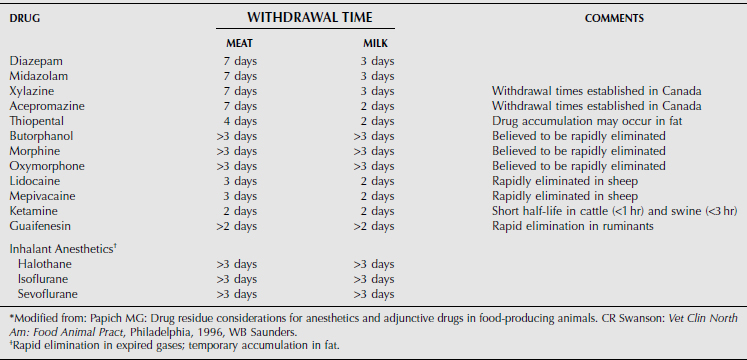

The use of local or regional anesthetic techniques in farm animals is preferred over general anesthetic techniques because of ease of administration, minimal equipment requirements, low cost, and reduced incidence of complications. Many surgical techniques, such as an abdominal exploratory, cesarean section, umbilical surgery, dehorning, enucleation, perineal surgery, or castration, can be performed with local or regional techniques. General anesthesia is reserved for more complicated surgeries or extremely painful procedures. Unlike general anesthetic procedures, holding the patient off feed is usually unnecessary. However, in some instances it may be useful to decrease the bulk of the rumen to allow better visualization and manipulation of abdominal viscera for procedures such as ovariectomy. Lidocaine hydrochloride is the most commonly used drug in farm animal practice for local and regional anesthesia. It has an analgesic duration of 90 to 180 minutes, and less than 100 mL of a 2% solution is usually sufficient, even for a large bovine. Other local anesthetics, including bupivacaine, mepivacaine, and procaine have been used, but they are all more costly and potentially more toxic—and therefore less popular than lidocaine. None of the local anesthetics is approved for use in farm animals in the United States; therefore clients must be advised of appropriate withdrawal times (see Table 6-5).

ANESTHESIA FOR ABDOMINAL SURGERY

Regional anesthesia in the bovine is most commonly used to access the abdominal cavity. This can be accomplished by a proximal paravertebral nerve block, distal paravertebral nerve block, infiltration anesthesia, segmental epidural anesthesia, and (in smaller animals) high epidural anesthesia. All provide anesthesia of the flank region for abomasal displacements, rumenotomy, cesarean section, or intestinal surgery.

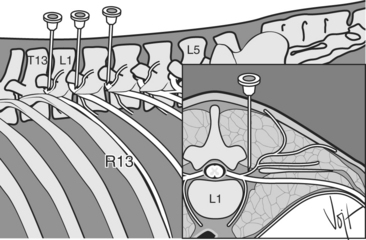

PROXIMAL PARAVERTEBRAL ANESTHESIA (FARQUHARSON, HALL, OR CAMBRIDGE TECHNIQUE)

Proximal paravertebral anesthesia provides excellent anesthesia of the entire flank region through blockade of the last thoracic (T13) and first two lumbar (L1 and L2) spinal nerves. The nerves are approached from the dorsal aspect of the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae. The ends of the transverse processes are palpated, starting caudally just in front of the tuber coxa with L5 and working cranially to the often very small, shorter, and harder-to-palpate L1. A 14-gauge, 1-inch needle is placed as a trocar 1 to 2 cm off dorsal midline, in line with the cranial aspect of the transverse process of L1 (Figure 6-1). A 5-inch, 18-gauge needle is then used to perform the nerve block through this trocar. The needle is passed ventrally until the transverse process is encountered (5 to 7 cm deep). The needle is then walked off the cranial edge of the process and passed ventrally to pene-trate the transverse ligament and fascia. After penetra-tion of the fascia, usually palpable as a “pop,” 10 to 15 mL of 2% lidocaine is injected. The needle is then withdrawn 1 to 2 cm so that the tip of the needle is above the fascia, where an additional 10 to 15 mL of lidocaine is injected. The authors recommend injecting an additional 2 to 3 mL of lidocaine as the needle is slowly withdrawn through the epaxial musculature to desensitize branches of the spinal nerves. Advantages of this technique include minimal amount of anesthetic required, a relatively large area of desensitization, no lidocaine in the incision site, and rapid onset of local anesthesia. Disadvantages of this technique include difficulty in finding landmarks in fat cattle, scoliosis and moderate ataxia, and risk of penetrating major blood vessels or the spinal canal.

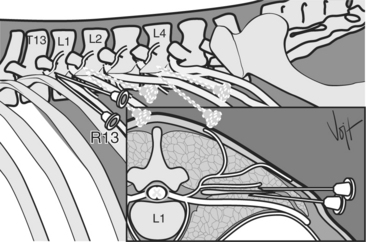

DISTAL PARAVERTEBRAL ANESTHESIA (MAGDA, CAKALA, OR CORNELL TECHNIQUE)

Distal paravertebral anesthesia provides excellent anesthesia of the entire flank region of the cow through blockade of T13, L1 and L2 at the tips of the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae. Injections are made with an 18-gauge, 1.5-inch needle inserted parallel to the tips of the processes of L1, L2, and L4 (Figure 6-2). Ten to 20 mL of 2% lidocaine is infiltrated in a fan-shaped area dorsal to the tip of the process, after which time the needle is withdrawn until it can be redirected ventral to the process and infiltration repeated with 10 to 20 mL of lidocaine. Advantages of this technique include lack of scoliosis and ataxia, reduced risk of penetrating large blood vessels or nerves, and the use of common-sized needles. Disadvantages include the increased amount of lidocaine required, variable position of nerves leading to incomplete or inadequate anesthesia, and difficulty in locating the transverse processes in fat cows.

INFILTRATION ANESTHESIA

Infiltration of lidocaine at or around the incision site can provide adequate analgesia for most minor surgical procedures. Infiltration anesthesia is usually performed by using a line block or an inverted-L or -7 pattern. The line block is performed by making multiple subcutaneous (1 cm deep) and deep (2-7 cm deep) injections of 1 to 2 mL of 2% lidocaine along a proposed incision line. Up to 100 mL of 2% lidocaine may be required in cattle, depending on the required incision size and thickness of the body wall. Small amounts of lidocaine are used for line blocks in small ruminants, especially goats, because of their sensitivity to the drug. When possible, lidocaine should be diluted to a 1% solution with equal parts of sterile saline before injection in small ruminants. Potential disadvantages of this technique include delayed healing as a result of lidocaine in the incision site, incomplete anesthesia of the deeper layers, increased amounts of lidocaine required, length of time required to perform the block, risk of toxicity, potential for sloughing of skin (especially if epinephrine is added to the lidocaine), and inability to extend the incision during surgery without additional lidocaine infiltration.

CAUDAL EPIDURAL ANESTHESIA

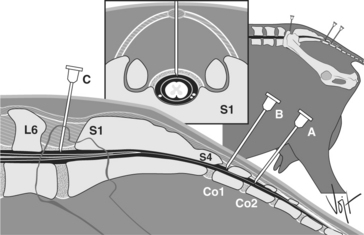

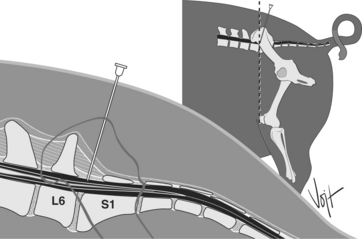

The caudal epidural is commonly performed in all farm animals. It is technically easy to perform and requires no special equipment. The location is the sacrococcygeal (S5-Cx1) or first coccygeal (Cx1-Cx2) space. The S5-Cx1 interspace is caudal to the spinal cord, and only the coccygeal nerves are present. The correct location is palpated by moving the tail up and down with one hand while palpating the dorsal spinous processes of the sacrum and coccygeal vertebrae with the other hand. The most proximal moving intervertebral space is the location for drug injection (Figure 6-3). The sacrococcygeal space is generally ossified in older animals, especially in cows. The intercoccygeal space is larger in most cows, thus making penetration of this interspace easier. An 18-gauge, 1.5-inch needle is used to penetrate the space directly on the dorsal midline in an adult cow. The needle is directed slightly cranially with the bevel in a lateral or cranial orientation to the animal. The needle is advanced until a “pop” is felt (usually 2 to 4 cm deep), thus indicating entrance into the epidural space. If the ventral floor is encountered, the needle is withdrawn slightly (1 cm) into the epidural space. The bevel is rotated cranially, and its position is checked by placing a few drops of lidocaine into the needle hub and waiting until the lidocaine is aspirated into the epidural space. Injection should be easy and without resistance. If previous epidurals have been performed or attempted, there may be no negative pressure to aspirate the lidocaine from the needle hub. Injection of 1 mL lidocaine per 100 kg body weight is recommended in adult cattle. This approximates 5 to 6 mL for an average adult cow. Larger doses may paralyze the spinal nerves to the hind limbs of smaller cattle, thus causing recumbency. Time to onset is usually 10 to 20 minutes, with a 30- to 150-minute duration range.

Caudal epidural anesthesia in small ruminants is performed by administering no more than 1 mL 2% lidocaine per 50 kg at the sacrococcygeal or first coccygeal space with an 18- or 20-gauge needle (see Figure 6-3).

CRANIAL EPIDURAL ANESTHESIA

Cranial epidural anesthesia (“high” epidural) can be performed for procedures as far cranial as the diaphragm, depending on the amount of local anesthetic used. A similar amount of anesthesia can also be obtained by administering larger volumes of lidocaine at the sacrococcygeal space (S5-Cx1) or the first coccygeal space (Cx1-Cx2), but ataxia and recumbency usually occur. The injection location is at the lumbosacral space (L6-S1). This L6-S1 space is palpable as a depression in the spinal column just caudal to a line drawn between the wings of the ilium (see Figure 6-3). The block is performed with a 3- to 5-inch 18-gauge needle. Similar to the caudal epidural, the needle is advanced through the skin and musculature to a depth of approximately 10 cm, where a sudden decrease in resistance should be felt. Testing of the location and injection are similar to the caudal epidural. The dosage of lidocaine is approximately 0.5-1 mL of 2% lidocaine per 4.5 kg body weight for cattle. At either of the lower epidural locations, 40 to 150 mL (average 80 mL) may be required for adult cattle and 5 to 25 mL (average 15 mL) in calves. The volume of lidocaine injected is determined by the animal’s response to the injection and the desensitization area size required by the procedure. The position of the animal affects local anesthetic distribution. Elevation of the head confines local anesthetic to the caudal region of the epidural space, whereas elevation of the hindquarters (not recommended) causes cranial migration of the anesthetic. Lateral recumbency provides lateral anesthesia, whereas dorsal recumbency provides bilateral distribution of the anesthesia. Care should be taken with high-volume infusions because improper positioning of the animal (elevated hindquarters) may lead to respiratory paralysis and death. Slow injection produces a smaller area of desensitization than does rapid injection. Cattle that are recovering from a “high” epidural should have excellent footing with their hind legs “hobbled” to prevent abduction of the hind limbs and damage to the inner thigh musculature.

The lumbosacral space is the only easily accessed epidural space in swine; therefore this site is preferred for administering a local anesthetic. The injection site is located in a similar place to that in ruminants, as a depression in the spinous processes between the wings of the ilium (Figure 6-4). Injection is made with an 18 or 20-gauge 3- to 7-inch needle. A 14-gauge, 1-inch needle may be used as a trocar. The dose for swine is the same as that for cattle (0.5-1 mL of 2% lidocaine per 4.5 kg body weight). Evidence suggests that a smaller dose may also work (1 mL per 7.5 kg, plus 1 mL for every 10-kg increase over 50 kg). Epidural xylazine has been examined in swine by using 2 mg/kg in 5 mL saline. This produced effective immobilization and analgesia for 120 minutes after administration. In sows, 1 mg/kg xylazine in 10 mL lidocaine produced anesthesia and analgesia of the hindquarters.

ANESTHESIA FOR PROCEDURES INVOLVING THE HEAD

Dehorning and ocular surgery are the two most common reasons for providing local anesthesia of the head in farm animals. Local anesthetic procedures are easily performed in standing animals in conjunction with adequate head restraint. Occasionally, anesthesia of other areas of the head, such as the nose, lips, and face is required.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree