CHAPTER 72 Facilitating Client Grief

As family pets have transitioned to the role of friends and confidants, many owners now believe that their cats provide a more stable and unconditional love than most human relationships.1 Consequently the loss of that emotional companion can be very damaging psychologically. Simplistically, grief is viewed as the emotional response to a personal loss, and in today’s society this loss often includes the death of a family pet. Of equal importance is the fact that grief also can present itself as physical, emotional, or behavioral changes.2 Thirty per cent of pet owners in a recent survey admitted to experiencing some level of grief after the death of their pet.2 Aiding clients through the grief process after the loss of a pet is now of fundamental importance to veterinarians treating companion animals.

RELAYING DIFFICULT NEWS

The first indication of how a client will handle the grieving process may be exhibited during the initial discussion of the pet’s condition. Indeed, it is exceptionally important that the veterinarian understand the subtleties of relaying “difficult news,” because veterinarians who are better trained and prepared for delivering this type of information have less anxiety toward the event and deliver the news in a more acceptable and compassionate manner to their clients.1

A working definition of difficult news would include situations in which there is a feeling of no hope, a threat to a person’s mental or physical well-being, a risk of upsetting an established lifestyle, or when a message is given that conveys to an individual fewer choices in his or her life.3 In reality difficult news is a relative term because all clients interpret and respond to information differently. In any case the veterinarian should relay the distressing information to the client in a consistent, caring manner, and should be prepared to take the time necessary to allow the client to have a full understanding of the pet’s condition.

The first step in relaying unfortunate news to the client is to select an ideal time.1 Whenever possible, bad news should be reported in person and by the veterinarian, rather than by a member of the support staff. Although particular emergency situations may not allow for a scheduled discussion, a diagnosis of cancer or other life-threatening illness usually can be discussed at the convenience of both the client and the veterinarian. Furthermore, the client’s support group of family and friends should be given the opportunity to attend the meeting.1,4

The location of the conversation also can influence a client’s response to the news substantially. The very busy waiting room or lobby offers obvious limitations, notably noise and lack of privacy. Ideally the room should be away from the busy flow of a normal practice, and should be arranged in a friendly, accommodating manner with comfortable seating and tissue paper available. Personnel who are not involved directly in this patient’s care should excuse themselves, because the lack of privacy can hinder the client’s need to express her or his grief and may invoke a stronger response.4

The veterinarian’s initial body language and attitude often set the tone for the entire conversation. A few deep breaths and a conscious decision to relax prior to entering the room can help to reassure the client. An anxious and unfocused veterinarian brings added stress to an already anticipatory situation.4 When conveying the news, the veterinarian should not have any furniture, including an exam table, or person between herself or himself and the client.4,5 Sitting or standing at or below the level of the owners reduces the intimidation associated with conversations with the veterinarian. Interacting with the cat while talking to owners helps to confirm your compassion toward the situation. Body language such as folded arms, or a short interpersonal distance, represents a forceful demeanor.5 Numerous studies have found that empathy from the veterinarian or physician influences the situation positively.1,4 Touching the client during difficult news is often viewed favorably by the client, but is not appropriate in all settings.4

Most veterinarians are able to gauge their clients’ ability accurately to comprehend medical explanations. Their ability to understand may be further diminished in this stressful setting and more simplistic verbiage may be required when bad news is presented.1 Should they desire it, owners usually will ask for a more scientifically complex explanation. Beginning with a statement that sets the tone for the conversation such as “Unfortunately, we have some bad news,” helps minimize the shocking effect of a declarative statement such as “We found cancer,” midway through the discussion.1,4

Inexperienced veterinarians often struggle with relaying a guarded prognosis for fear of being associated with the bad news, a well-documented phenomenon for many physicians.1 Although it is acceptable to always offer some level of hope, unrealistic expectations, even if beneficial in the early stages, eventually will lead to a more devastating reality and grieving process when death of the pet occurs. Phrases such as, “We expect the cancer to behave in a particular way, but every disease has unique behavior in each pet” can be used to convey the small chance of hope without undermining the justifiably poor prognosis. Most clients are grateful for an honest answer or disease description at the beginning of the discussion.

Many clients are overwhelmed by the gravity of the news and the extent of the information. Whenever possible, allow for questions throughout the conversation.4 This is not a lecture at a podium; it is a very delicate discussion about their pet. Set the pace of the conversation to meet the needs of the client.4 Sending follow-up discharge instructions allows the owner to further process the information in the privacy of their home. Discharge instructions also may provide a more scientific explanation that allows the owner the opportunity for further research.1,4 Finally, visual aids can be excellent tools for relaying the gravity of a medical condition. Visualizing the size and extent of a tumor on a radiograph, ultrasound, computed tomographic image, or magnetic resonance image certainly can facilitate your explanation of the severity of a disease process. Even showing normal laboratory parameters compared with their cat’s values can be a very helpful visual exercise to increase understanding of the scale of the illness.

EUTHANASIA

DECIDING WHEN IT IS TIME FOR EUTHANASIA

For many chronic diseases, including cancer, the decision for euthanasia typically is a process requiring numerous conversations; only rarely does the owner need to make a decision immediately. It is helpful to introduce the owner of patients with terminal cancer to the concept of euthanasia very early in the disease process.6 At the time of diagnosis, trigger phrases such as “terminal disease” and “noncurable” are repeated so that owners have a true understanding of the expected disease progression. Furthermore, detailed explanation of the predicted decline of the pet will forewarn clients of the changes anticipated in the future.

Many owners are fearful that they will be unable to recognize when the time for euthanasia is appropriate. For these situations, the authors routinely recommend the “Rule of Three.”7 The owners are encouraged to remember their pet at its healthiest time (which may or may not be the time of diagnosis). During that period of the pet’s life, a list of the pet’s three favorite activities should be made. When a pet can not accomplish two of the three activities on that list, quality of life is reasonably compromised and euthanasia should be considered. The owners are encouraged to write down the “Rule of Three” because writing down the activities serves two purposes. First, the list is easier to remember and less likely to be forgotten conveniently during emotional distress. Second, a written list serves psychologically as a contract for the owners that should not be broken, even in times of severe grief and confusion. The authors have found great success in helping owners recognize significant decline in patient quality of life before true patient suffering occurs when the “Rule of Three” is implemented early in the disease process. Other options include discussing a list of eventual clinical signs of disease and a hospital-designed brochure on planning for death and euthanasia that may be given to owners at the onset of their pet’s diagnosis.6,8

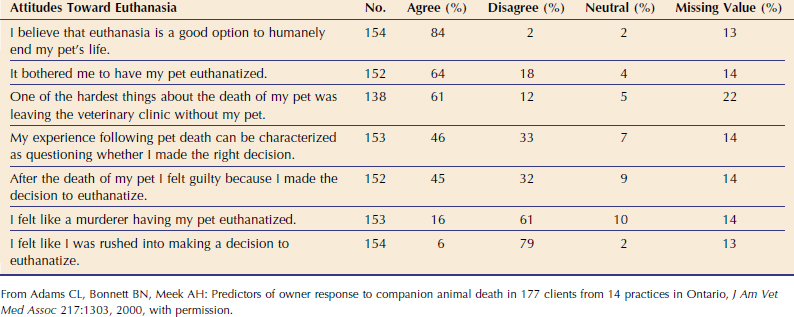

It is exceptionally important to provide a support network when owners elect euthanasia for their pets.9 It should be noted that 16 per cent of owners in a recent euthanasia survey felt that the decision to euthanize their pet was equivalent to murder and views of euthanasia are wide ranging among owners (Table 72-1).2 The ethical dilemma of euthanasia for healthy or adoptable pets will not be discussed here. Instead, the focus will be on euthanasia decisions for those pets with terminal disease or severe injury. Owners elect euthanasia for a variety of reasons. Financial limitations should not invoke a judgmental reaction from the veterinarian or her/his staff. Even the slightest hint of judgment could influence these owners to delay euthanasia for a future pet because of unnecessarily held guilt, because up to 50 per cent of owners admit to some level of guilt after euthanizing their pets.2 Additionally, casual use of certain words such as “stop” or “quit” should be avoided because they imply that the owner has abandoned her or his pet. This belief in abandonment can extend and increase the severity of the grieving process. Empathy from the veterinary staff concerning the difficulty in their decision is imperative to the owners’ future mental health.9,10

THE PROCEDURE

Once the decision of euthanasia has been made, a checklist of steps should be used to ensure that the emotional event occurs as smoothly as possible. Legal authorization should be obtained as quickly as possible. The initial euthanasia discussion should focus on whether or not the owners, specifically children, would like to be present for the procedure.6 Although it is an added stress to the veterinarian, it is important for some owners to witness the process, because many clients need to make sure the procedure was not traumatic to their pet.11 Decisions regarding the pet’s remains (cremation, burial, or routine disposal) also should be discussed because owners often feel angry or suspicious if this information is not offered.9

All veterinary hospitals should have an established hospital policy on billing for euthanasia. The authors’ hospital provides a mailed bill to clients in good standing. If payment is required, it may be best to collect the fees prior to the procedure so that an emotional client can avoid a crowded waiting room after the loss of their pet. Finally, as with all end-of-life discussions, clients appreciate an explanation of the euthanasia process.9 Medical jargon is not required, but a brief explanation of the mechanisms of action of the drug used in euthanasia helps to eliminate the owners’ fears of pet suffering during the procedure.

A veterinary hospital should develop routine procedures for euthanasia to ensure that mistakes are minimized. The trauma of a poorly placed catheter and subsequent slow death can haunt an owner for years. Provide medical proof that the animal has died, either via auscultation or palpation of a pulse. Confirm that the patient is dead or passed away; avoid terms such as sleeping or gone, as use of these phrases may be particularly confusing to children who are present.10 Based on client surveys, owners should be allowed to spend time with their pet both before and after the euthanasia is performed; most owners take no more than 15 to 20 minutes to say goodbye.9,11,12 As stated previously, allowing owners to leave from an exit other than the waiting room may help them feel more comfortable in their distressed emotional state.6,9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree