Chapter 9

Eyes and Associated Structures

General Considerations

Microscopic Evaluation

Ocular specimens are often small in volume, and therefore examination of the entire sample is easy. The observer should be familiar with the normal cytologic and histologic characteristics of the tissue sampled and recognize cellular patterns, other structures, and background material.1,2 Identification of specific types of inflammatory cells permits classification of inflammation as neutrophilic (synonyms include suppurative and purulent); eosinophilic (often accompanied by mast cells); lymphocytic–plasmacytic; mixed, including pyogranulomatous; and granulomatous. If neoplasia is suspected on the basis of the presence of a mass and a homogenous population of noninflammatory cells, the observer should be able to identify the cell type (epithelial, mesenchymal or connective tissue, and discrete round cells) and the cytologic features of benign and malignant tumors. It is important to recognize that neoplasms can induce an inflammatory response. Finally, the observer should be familiar with the cytologic characteristics of cysts, acute and chronic hemorrhage, and degenerative diseases.

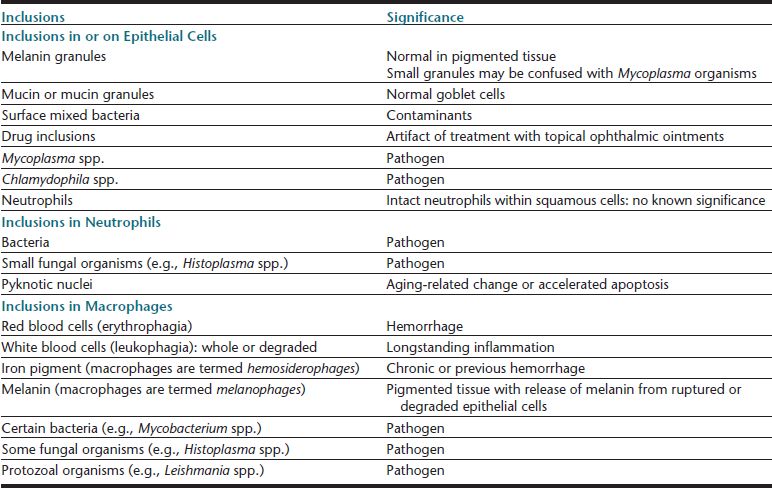

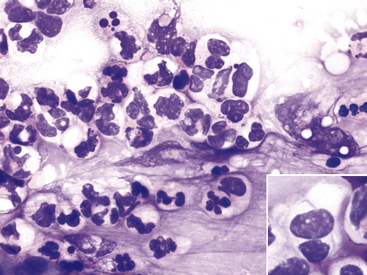

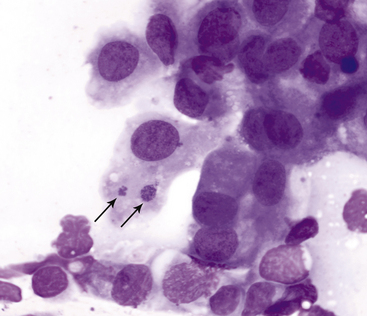

When identifying cell types, it is essential to examine cells in an area where they can be evaluated individually. However, thick collections of material—often consisting of clustered epithelial cells, aggregates of mesenchymal cells, or necrotic material—tend to be understained, and cells with granules that stain more readily than other components (mast cell and eosinophil granules), naturally pigmented elements (melanin), bacteria, and fungal hyphae may be visualized within or on top of the thick tissue (Figure 9-1). Inclusions found in epithelial or inflammatory cells may be normal elements, artifacts of treatment, or evidence of the pathologic process or etiology (Table 9-1). Normal tissue also may be present.

Figure 9-1 Thick understained tissue from two corneal scrapes in which significant structures or cells may be visualized.

A, Eosinophils and eosinophil granules (arrows). B, Fungal hyphae (arrows). (Wright stain, original magnification 200×; insets 600×.)

Once a category is identified, a more specific diagnosis may be possible. For example, search for an etiologic agent is indicated if inflammation is present. At the very least, the category can guide additional testing or therapy. Special cytologic features of neutrophils, epithelial cells, and extracellular material (Table 9-2) often provide additional information about the pathologic process; misinterpretation of these features (e.g., mistaking free mast cell granules for bacterial cocci) could lead to erroneous conclusions.

Eyelids

Blepharitis

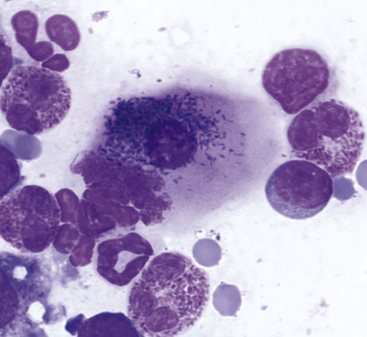

Blepharitis may be focal or diffuse and acute or chronic; bacterial, mycotic, parasitic, allergic, or immune-mediated blepharitis may occur. The objectives in cytologic examination of lesions of blepharitis are to characterize the type of exudate (neutrophilic, lymphocytic–plasmacytic, eosinophilic, or granulomatous) and search for the causative agent. Agents that may be encountered in scrapings are Sarcoptes spp., Demodex spp., dermatophytic yeast, and bacteria. Demodex folliculorum causes minimal exudation. Bacterial blepharitis, particularly staphylococcal blepharitis, has a neutrophilic exudate. Certain fungi, such as Blastomyces dermatitidis, cause either a primarily neutrophilic or a pyogranulomatous exudate, whereas others cause a granulomatous exudate composed of macrophages, including epithelioid forms, and giant cells. Foreign bodies may elicit a pyogranulomatous or granulomatous response (Figure 9-2).

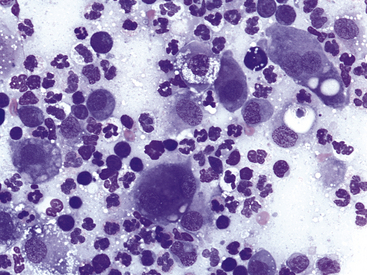

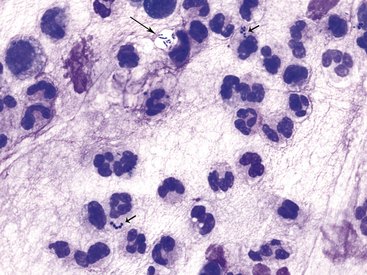

Figure 9-2 Pyogranulomatous inflammation in the eyelid of a dog.

Note neutrophils and epithelioid macrophages, including binucleate forms. Lymphocytes and low numbers of red blood cells also are present. (Wright stain, original magnification 600×.)

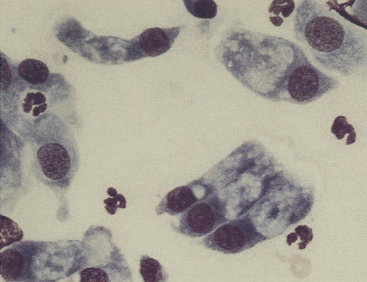

Discrete Masses

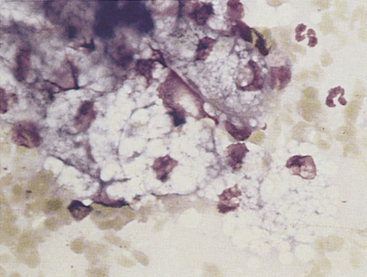

Discrete masses on the eyelids may be neoplastic (benign or malignant) or nonneoplastic. Among neoplasms, benign sebaceous gland tumors (sebaceous adenoma, sebaceous epithelioma) are the most common type on canine eyelids. The glands of Zeis and Moll at the eyelid margin and the meibomian glands, which lie beneath the palpebral conjunctiva and open at the lid margin, are all of the sebaceous type; tumors arising from them are similar to cutaneous sebaceous gland tumors. The cells are readily recognized by their voluminous vacuolated cytoplasm that nearly obscures small rounded nuclei (Figure 9-3). The malignant counterpart of these tumors is rare on the eyelids.

Figure 9-3 Sebaceous gland epithelial cells from a well-differentiated sebaceous gland tumor on a canine eyelid. (Romanowsky-type stain, original magnification 1000×.)

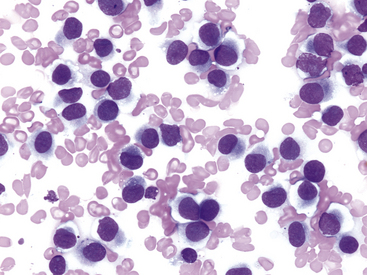

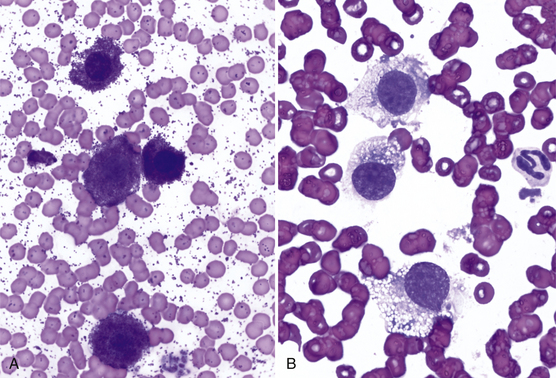

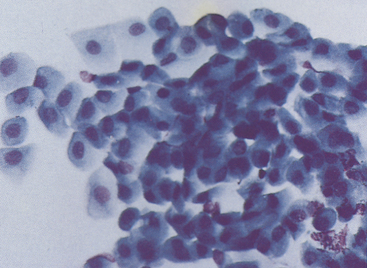

Other tumors frequently encountered on the eyelids and readily diagnosed by cytologic examination include melanoma (benign and malignant), histiocytoma (Figure 9-4), lymphoma, mast cell tumor (low and high grade) (Figure 9-5), papilloma, and squamous cell carcinoma. Squamous cell carcinomas are frequently ulcerated. In mast cell tumors, mast cell granules sometimes are not visible if quick stains are used (see Figure 9-5, B). Other carcinomas and connective tissue tumors (fibrosarcoma, hemangiosarcoma, histiocytic sarcoma) occur less frequently and are discussed in Chapter 2.

Figure 9-4 Discrete round cell tumor with cytologic characteristics of a histiocytoma on the eyelid of a dog. (Wright stain, original magnification 600×.)

Figure 9-5 A, Well-granulated mast cell tumor on the eyelid of a dog. (Wright stain, original magnification 600×.) B, The same specimen stained with a quick stain. Note that mast cell granules did not stain. (Diff-Quik stain, original magnification 600×.)

Ocular idiopathic adnexal granulomas may simulate neoplasms, be bilateral, and be a component of systemic granulomatous disease.3 Systemic histiocytosis of Bernese Mountain Dogs causes periocular granulomatous masses.4,5 True cysts can occur on the eyelids and typically contain foamy macrophages and cholesterol crystals from epithelial degeneration (Figure 9-6).

Conjunctiva

The primary goals for conjunctival cytologic evaluation are characterization of an exudate and identification of the cause of conjunctivitis. Certain anatomic structures affect the types of cells found on all preparations from normal and diseased eyes. The conjunctiva is composed of two continuous layers of epithelium that lie in apposition. The inner epithelial layer of the eyelid, called the palpebral conjunctiva, is composed of pseudostratified columnar epithelium and interspersed goblet cells (Figure 9-7). Cilia may be found on the columnar cells. At the fornix, deep within the conjunctival sac, the epithelium reflects back over the globe. This bulbar conjunctiva is composed of stratified squamous epithelium (Figure 9-8). Bulbar conjunctiva is continuous with the corneal epithelium at the limbus. The squamous cells are noncornified and often contain melanin granules (Figure 9-9). In most conjunctival scrapings, squamous cells are more numerous than columnar cells. In animals treated with topical ophthalmic ointments (particularly neomycin), epithelial cells may contain dense basophilic homogeneous cytoplasmic inclusions (Figure 9-10).6 Such inclusions must be differentiated from infectious agents. At the fornix, conjunctival lamina propria contains lymphoid tissue; various types of lymphoid cells may be found in any conjunctival scraping. Without clinical signs of conjunctivitis, little emphasis should be placed on the observation of lymphocytes or plasma cells among epithelial cells.

Figure 9-7 Canine conjunctival scraping contains palpebral columnar ciliated cells and goblet cells. (Romanowsky-type stain, original magnification 1000×.)

Figure 9-8 Basal, intermediate, and mature noncornified squamous cells typical of bulbar conjunctival epithelium from a canine conjunctival scraping. (Romanowsky-type stain, original magnification 400×.)

Figure 9-9 Conjunctival scraping from a cat.

An epithelial cell contains numerous melanin granules. (Wright stain, original magnification 1000×.) (From Young KM, Taylor J: Laboratory medicine: yesterday-today-tomorrow. Eye on the cytoplasm, Vet Clin Pathol 35:141, 2006. Reprinted with permission of the American Society for Veterinary Clinical Pathology.)

Figure 9-10 A corneal scrape contains squamous cells with dense, homogeneous, blue cytoplasmic inclusions believed to be a consequence of treatment with ophthalmic ointment. (Wright stain, original magnification 600×.) (From Young KM, Taylor J: Laboratory medicine: yesterday-today-tomorrow. Eye on the cytoplasm, Vet Clin Pathol 35:141, 2006. Reprinted with permission of the American Society for Veterinary Clinical Pathology.)

Cytologic preparations from the conjunctiva should include freshly derived cells. If external debris within the conjunctival sac is present, imprints of the debris should be made because this material may contain the etiologic agent such as Blastomyces spp. More often, the debris obscures the primary lesion; therefore, after imprints are made, the debris should be removed and conjunctival scraping performed with a flat, round-tipped spatula. Preparation of bulbar conjunctival imprints using filter strips following topical anesthesia has been reported in dogs.7

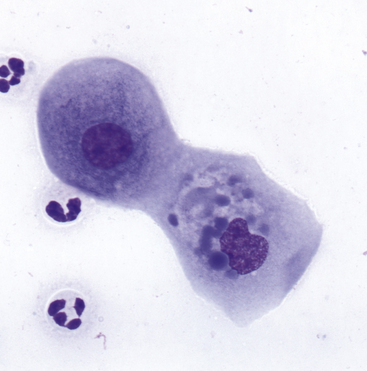

Neutrophilic Conjunctivitis

Canine and feline conjunctivitis frequently is neutrophilic and results from bacterial or viral infections, allergic disease, or other causes. Pseudomembranous (ligneous) conjunctivitis is neutrophilic.8 Cytologic evaluation may not reveal the cause. Neutrophils may be nondegenerate or degenerate (Figure 9-11); in cats, the latter are rarely encountered. In both dogs and cats, intact neutrophils may be found within squamous cells, and the significance of this finding is unknown. Mucus is a common component of neutrophilic exudates and may cause cells to be aligned in rows on the smear.

Figure 9-11 Conjunctival scrape from a dog with neutrophilic bacterial conjunctivitis.

Both well-segmented nondegenerate neutrophils and degenerate neutrophils with swollen nuclei are present. (Wright stain, original magnification 600×.) Inset, A degenerate neutrophil with two thin bacterial rods. (Wright stain, original magnification 1000×.)

The exudate of canine neutrophilic conjunctivitis often contains bacteria, regardless of the primary cause. Bacteria are often large or small cocci and less frequently rods (Figure 9-12). The dilemma is determining whether the bacteria are of primary importance or are merely opportunistic. Normal bacterial flora of the canine conjunctival sac have been described.9 Keratoconjunctivitis sicca is a common canine disorder causing neutrophilic exudate in which bacteria frequently are encountered. The disease is diagnosed readily by the Schirmer tear test. In contrast to that of dogs, the exudate of feline neutrophilic conjunctivitis rarely contains bacteria. When observed, bacteria should be considered clinically significant in feline conjunctivitis.

Figure 9-12 Conjunctival scrape from a dog.

Note many neutrophils and bacterial rods (long arrow) and cocci (short arrows). (Wright stain, original magnification 1000×.)

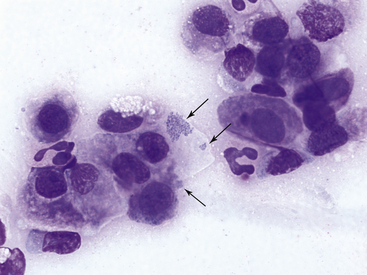

Distemper is the most important viral cause of canine neutrophilic conjunctivitis. Canine distemper is diagnosed on the basis of its classic clinical signs and fluorescent antibody staining of conjunctival smears. Canine distemper inclusion bodies in epithelial cells are found rarely (Figure 9-13), and a search for them has limited diagnostic value.

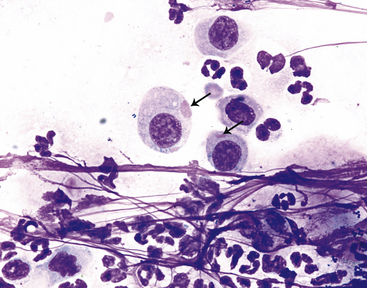

Figure 9-13 Conjunctival scrape from a dog.

Variably sized distemper viral inclusions (arrows) are found within epithelial cells. Note neutrophils and small bacterial rods and cocci. (Wright stain, original magnification 1000×.) (Photomicrograph by Judith Taylor; from Young KM, Taylor J: Laboratory medicine: yesterday-today-tomorrow. Eye on the cytoplasm, Vet Clin Pathol 35:141, 2006. Reprinted with permission of the American Society for Veterinary Clinical Pathology.)

Neutrophils also predominate in the conjunctival exudate of feline chlamydial infection. In experimental Chlamydophila felis infections, organisms were found on day 6 postinoculation, after clinical signs first appeared.10 Solitary, large (3 to 5 micrometers [µm]), basophilic particulate forms initially are found in the cytoplasm of squamous epithelial cells (Figure 9-14). The particulate nature of the initial body is an important observation to distinguish C. felis from incidental foci of homogeneous cytoplasmic basophilia found in squamous epithelial cells (Figure 9-10); organisms also may appear as aggregates of coccoid basophilic bodies (elementary bodies), measuring 0.5 to 1 µm in diameter (Figure 9-15).11 In experimental infections, organisms rarely were found by day 14 after inoculation, and in chronic conjunctivitis, intracytoplasmic organisms are present only infrequently.10,12 Chlamydial conjunctivitis may be confirmed by PCR analysis or fluorescent antibody staining. Chlamydiae other than C. felis also may play a role in ocular disease in cats.13

Figure 9-14 Initial body of Chlamydophila felis in the cytoplasm of a squamous cell in a conjunctival scrape from a cat. (Romanowsky-type stain, original magnification 1000×.)

Figure 9-15 Conjunctival scraping from a cat with chlamydial conjunctivitis.

Elementary bodies of Chlamydophila felis are found in an epithelial cell (arrows). (Wright stain, original magnification 1000×.) (From Young KM, Taylor J: Laboratory medicine: yesterday-today-tomorrow. Eye on the cytoplasm, Vet Clin Pathol 35:141, 2006. Reprinted with permission of the American Society for Veterinary Clinical Pathology.)

Feline mycoplasmosis, another cause of neutrophilic conjunctivitis, may be diagnosed by finding the organisms on epithelial cells on routinely stained smears. In one study, mycoplasmosis was diagnosed in nine naturally infected cats by isolation and identification of Mycoplasma spp. Of samples from 16 eyes, the organisms were found on Romanowsky-stained smears from 15 eyes, suggesting a high degree of diagnostic sensitivity for routine cytologic evaluation in Mycoplasma infection.14 Other studies have found cytologic examination to be less reliable in the diagnosis of mycoplasmosis.11 The basophilic organisms, 0.2 to 0.8 µm long, may be found in clusters adherent to the outer limits of the plasma membrane or over the flattened surface of squamous epithelial cells (Figure 9-16). They also may be seen in clusters between cells. Mycoplasma organisms should not be confused with melanin granules (Figure 9-9).

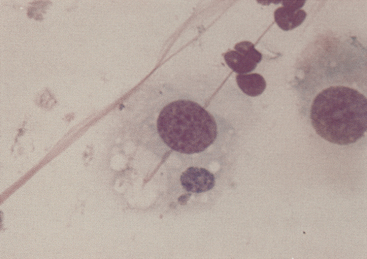

Figure 9-16 Conjunctival scraping from a cat with mycoplasmal conjunctivitis.

Mycoplasma felis organisms (arrows) are visible on the surface of and adjacent to an epithelial cell. Note neutrophilic inflammation. (Wright stain, original magnification 1000×.) (From Young KM, Taylor J: Laboratory medicine: yesterday-today-tomorrow. Eye on the cytoplasm, Vet Clin Pathol 35:141, 2006. Reprinted with permission of the American Society for Veterinary Clinical Pathology.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree