Chapter 1 Examination of the Surgical Patient

Physical Examination

Examination of the gastrointestinal tract includes evaluation of the abdominal shape for evidence of distension or bloat, auscultation of the rumen and intestinal motility, simultaneous auscultation and percussion (pinging), ballottement, and rectal examination. Ancillary diagnostic tests such as abdominocentesis, rumen fluid analysis, and passage of an ororumen tube can be performed to help differentiate the exact diagnosis. This chapter will now be divided into two main categories preceded by discussion of ancillary diagnostic tests: disorders that cause abdominal distension and those that cause tympanic resonance.

Diagnostic Procedures

RUMEN FLUID ANALYSIS

Rumen fluid can be obtained by passing an ororumen (stomach tube into the rumen) tube, weighted tube, or by rumenocentesis. The smell and color of the fluid obtained can be evaluated subjectively. Rumen fluid is generally aromatic, and, depending on the diet of the cow, the color can range from green to yellow to brown. A milky-to-brown color with a very pungent sour or acidic odor indicates grain engorgement (Figure 1-1). The presence of multiple small bubbles giving rise to a “frothy” appearance defines a frothy bloat. Depending on the diet, the normal pH ranges from 5.5 to 7.5; pH below 5.5 indicates rumen acidosis. Contamination of the rumen fluid with bicarbonate-rich saliva is the most common reason for a high rumen fluid pH. Pathologic reasons for a pH greater than 7.0 include decreased activity of the rumen flora, whereas a pH greater than 8.0 suggests urea toxicity. Other special tests—such as a Gram stain and direct microscopic examination for protozoa, methylene blue test, and sediment activity test—have been described but often do not have a practical application for the veterinarian in the field and provide little information other than what can be gained from a good physical assessment of the cow. A high rumen chloride (>30 mEq/L, normal <25-30 mEq/L) is consistent with reflux of chloride from the abomasum into the forestomachs and supports a diagnosis of pyloric outflow obstruction (posterior functional stenosis).

Ororumen Tube

The Kingman tube is a large-diameter tube that is used to evacuate abnormal rumen contents or for rumen lavage to alleviate the need for surgery or decrease abdominal distension in preparation for surgery. The cow’s head must be held straight, forward, and slightly raised above horizontal. A speculum is placed in the oral cavity; copious lubrication is applied to the tube, and with gentle pressure, it is passed down the esophagus to the rumen (Figure 1-2).

Abdominocentesis

Peritoneal fluid can be helpful in establishing a diagnosis and determining a prognosis for many gastrointestinal disorders. Two sites are recommended for abdominocentesis in cattle. The first evaluates the right cranial abdomen and is most helpful in cases in which a localized peritonitis is suspected secondary to perforation of an abomasal ulcer. This area runs from the midline to the right milk vein just caudal to the xiphoid. The second site is located just above the udder on the right side under the fold of the flank. The site is clipped and prepared for an aseptic procedure. A tail-jack is used for restraint and an 18-gauge, 1½ needle is inserted through the skin and slowly advanced into the peritoneal cavity. Alternatively, the area can be infused with lidocaine, a small stab incision made in the body wall with a 15 blade, and a teat cannula used to obtain the abdominal fluid. Cattle have very strong abdominal musculature that can move the needle or teat cannula; therefore they should be held carefully and kept at a 90-degree angle to the ground (see Figure 10.5-4). If available, ultrasonographic evaluation of the abdomen may reveal free peritoneal fluid, and if the fluid is not near any vital structures at risk of being perforated, then the abdominocentesis can be done at that particular site. Because cows produce copious amounts of fibrinogen, the fluid may be difficult to obtain and preparation of both sites for abdominocentesis may be more efficient. A normal abdominal fluid analysis in one location and an inflammatory tap in the other may indicate a localized problem. The fluid should be clear and colorless to yellow. The total protein should be <3.0 g/dL and the nucleated cell count <10,000/μL, consisting of neutrophils and mononuclear cells.

LABORATORY WORK

Strangulating lesions of the abomasum, cecum, or small intestine can result in bowel necrosis and accumulation of lactic acid. This can cause a high anion gap, hypochloremic acidosis indicating a poor prognosis. Infrequently, a moderate to severe case of ketosis may result in a high anion gap acidosis caused by ketoacidemia. On a practical basis, easy-to-use cow-side tests such as the I-stat* can determine plasma electrolyte levels, ionized calcium, and creatinine in less than 2 minutes per test.

Complete blood cell counts can quantitate the degree of inflammation and be run sequentially to monitor the patient’s response to a disease entity. A persistent lymphocytosis and clinical signs of pyloric obstruction could make the clinician suspicious that the cow is infected with bovine leukosis virus (BLV) and may have abomasal lymphoma. However, very few cattle infected with BLV (<4%) actually develop tumors. Increased concentrations of fibrinogen, an acute phase protein along with globulins, contribute to an overall increase in total plasma protein and are typical of an inflammatory process such as an intraabdominal abscess or peritonitis. An increased PCV and total protein supports dehydration.

Disorders Causing Abdominal Distension in Cattle

VAGUS INDIGESTION

Vagus indigestion (VI) is rumen atony caused by damage or inflammatory changes to the vagus nerve as it courses through the pharynx, thoracic cavity, and perireticular and pyloric regions. The vagus nerve provides both sensory and motor innervation to the bovine forestomach compartments and abomasum. Like other neurologic disorders, the cause of VI is determined after localizing the lesion and four types of vagal indigestion have been defined: 1) failure of eructation; 2) omasal transport failure or anterior functional stenosis; 3) pyloric outflow obstruction or posterior functional stenosis; and 4) indigestion of late pregnancy based on the site that the vagal nerve has been affected. The editors have modified this classification (see Section 10.3). In Types II and III, the term stenosis is not entirely correct because there is no true narrowing of the tract; however, there is a functional blockage or paralysis and relaxation whereby ingesta is unable to traverse the omasum to the abomasum or the abomasum to the pylorus and duodenum, respectively. Alternatively, one could approach a cow with VI by examining the pharynx, neck, thorax, and cranial abdomen for lesions that may involve the nerve as it courses through those respective locations. Cows with VI may have low heart rates (40 to 60 beats per minute), and the rumen, on auscultation, will have frequent, small, uncoordinated contractions. Feces tend to be scant and pasty with larger particulate matter due to inappropriate passage of feedstuffs. The most common causes of VI include traumatic reticuloperitonitis or hardware disease, reticular abscess (usually involving the medial wall of the reticulum), liver abscesses (right cranial and ventral aspect of the liver), pneumonia, postabomasal volvulus, and abomasal ulcers.

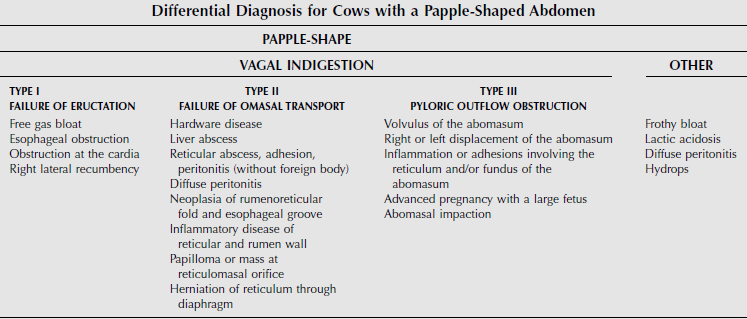

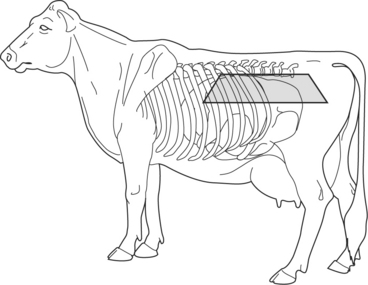

A great deal of information can be gained from standing behind a cow and observing the abdominal contour. Viewing the cow from either side and evaluating the shape of the paralumbar fossa and rib cage can also be helpful. The “papple” shape is classic for a cow with rumen distension in which the distended dorsal sac of the rumen occupies the dorsal left flank and the ventral sac of the rumen distends to not only fill the left ventral abdomen but also to distend over into the right ventral abdomen, thus giving an apple shape to the left side and a pear shape to the right side (Figures 1-3 and 1-4). The challenge is to determine the type and cause of the distention (Table 1-1). Auscultation of rumen motility, palpation of the rumen in the paralumbar fossa, accompanied by simultaneous auscultation and percussion (pinging) and succession, rectal examination, and rumen fluid analysis can be helpful in differentiating between these disorders. Other less common rule outs for distension of the entire left abdomen and right ventral abdomen include advanced pregnancy, hydrops, and abomasal impaction.

I—Failure of Eructation

With ruminal distention caused by free gas, a large ping can be heard dorsally on the left side of the abdomen beginning in the caudal left paralumbar fossa (as far back as the tuber coxae) and extending cranially to the eighth to tenth intercostal spaces (ICSs). The ping can also be heard dorsally over the midline (above the transverse processes of thoracic and lumbar vertebrae) with free gas rumen bloat. The ventral border of a rumen ping commonly has a very distinct horizontal line that distinguishes it from the tympanic resonance of a left-displaced abomasum (Figure 1-5). The rumen tends to be static in cows with free gas bloat, and the area of the ping corresponds to a palpably taut elastic tension on the external abdomen. The dorsal sac of the rumen on rectal examination will feel tight and rebounds when indented. The dorsal sac of the rumen can extend to the right past the midline, whereas the ventral sac may also be palpable because it is distended with feed material. An ororumen tube (if passed in a manner that successfully reaches the trapped gas) can relieve the gas, and the ping and rumen distension palpated on rectal examination will decrease, thus confirming suspicion of free gas bloat.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree