Chapter 13 Equitation science

Chapter contents

Background

There are a number of reasons for training problems. Many of them are considered from an ethological perspective in Chapter 15. They also include inconsistencies in the terms that are used, what is understood by them and the way in which training techniques are applied. The current chapter explores what horses can learn from their interactions with humans and encourages readers to engage with the emergent discipline of equitation science.

Horses for courses

It is important to be mindful that the behavioral responses required of horses, even at the highest level of dressage, are not beyond their physical capabilities. While physical limitations due to conformation may affect the quality of the training outcome (see Ch. 7), dressage movements are essentially derived from natural movements innate to the species.

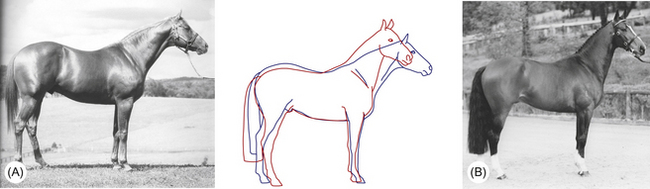

The sorts of conformation problems that limit performance in dressage and jumping generally involve the height ratio of the wither and the croup. If the wither is substantially lower than the croup, then horses generally have some difficulty collecting, which is a critical component of dressage and jumping training. Such croup-high horses are frequently found in the breeds selected for speed, such as Arabians and Thoroughbreds, and incidentally in the plains zebra (E. burchelli). Conversely, wither-high horses, such as all of the draft breeds, have formed the genetic basis of the modern performance dressage and jumping horse (Fig. 13.1). Interestingly, as the speed and endurance phase of three-day-eventing has become progressively reduced due to welfare considerations and, correspondingly, the relative influence of dressage phase on overall performance has increased, the predominance of the Thoroughbred in that sport is now giving way to the slower and less enduring but dressage-designed warmbloods (draft and Thoroughbred crossbreds). The emphasis in dressage on so-called uphill (i.e. withers-high) conformation is likely to have contributed to the breeding of foals that, quite without training, show a positive diagonal advanced placement at the trot in that the hindfoot of a diagnonal pair commences the stance phase before the corresponding forefoot. Horses with this action even before any training seem to command a premium price but whether this type of gait truly remains a trot (which, by definition, has a two-time beat) is the subject of current debate. Some commentators are concerned that selection of extraordinarily flamboyant forelimb action that can impress dressage judges may compromise the purity of gaits.

Traditional dogma

Despite empirical data that demonstrate the phenomenal memories of equids1,2 and the likelihood that horses do not need to be reminded how to execute their schooling tracks, trainers remain committed to regular schooling activities that usually comprise repetitive maneuvers involving 10-m circles, 20-m circles, serpentines and so on. If horses can indeed learn after a single trial only,3 it could be argued that these exercises are of more importance to riders than to horses. At the same time many riding tutors maintain that through such drilling the horse develops the musculature required to maintain self-carriage (see Glossary) without having learned anything. This circumvention of the need for any understanding of learning theory is unfortunate because it contributes to the mystification of equestrian technique by denying the central role of negative reinforcement.

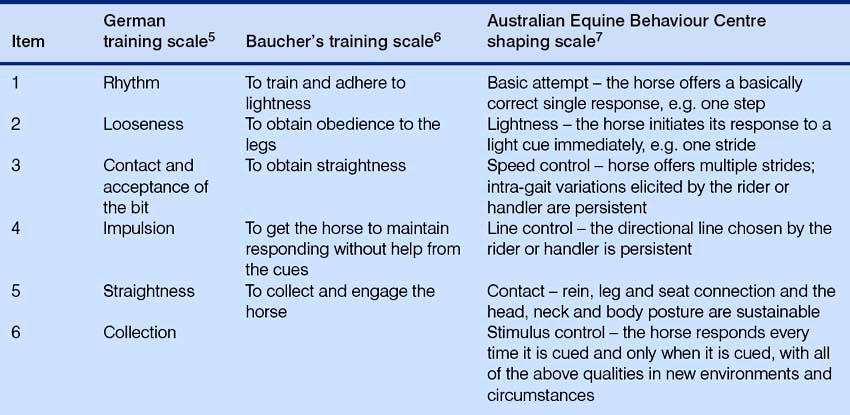

An industry survey (reported by Harris4) notes that 25% of the time owners spend with horses involves schooling (Fig. 13.2). Riders should be clear about the purpose of this activity. The aim in the preparatory work for each schooling session should be to assess the progressive qualities of the horse’s basic responses within each gait (immediacy of reaction, reaction to the light cue, rhythm, straightness, adjustability, suppleness and unconditional responses – does the horse give the same response wherever and whenever the rider signals?). Clearly, optimizing these outcomes will tend to improve the horse’s dressage scores. Show-jumping and eventing, if executed correctly, also rely on the same principles, i.e. rhythm (self-maintained rhythm and speed), straightness (self-maintained line and body straightness), and contact (self-maintained leg, seat and rein connections and outline). At any speed, the more correct the execution of turns and lines, the better the performance. Therefore, instead of slavishly tracing circles in the manège, riders should aim to refine the horse’s responses through a process of shaping (see Ch. 4). Effective shaping relies on the trainer delaying the reinforcement until the animal offers a closer approximation of the desired response than has been established in the past. In equitation, it demands attention to the placement of each foot to obtain exquisite control of locomotion, preferably before the trainer focuses on qualities such as neck flexion and outline. The concept of a training scale in equestrian manuals often departs from the notion of linear improvements. For example, the German scale (Table 13.1) does not address the acquisition of a basic attempt or stimulus control and therefore lightness of the pressure signals. In the German scale, straightness is designated to be trained after impulsion. Since impulsion requires bilaterally uniform power from the horse and straightness implies even power of the legs (a horse that is not straight is drifting), we challenge the veracity of the German scale. Straightness and rhythm are interdependent and as such should be adjacent on a training scale.

Figure 13.2 Horse being schooled.

(Reproduced by permission of the University of Bristol, Department of Clinical Veterinary Science.)

Shifting the mindset

The prevailing mindset throughout history has been to abandon, one way or the other, the less ‘willing’ equids because they have been regarded as having some moral (and even spiritual) involvement in the training process so that they are assumed to have ‘decided’ that they would not comply. These are the horses that, instead of learning what is required of them, learn to resist and escape and become the bolting, jibbing, balking, refusing, rearing, bucking and shying animals that are regularly described in books on so-called problem horses. These are the animals that change hands rapidly with the consequent addition of different commands and consequences that exacerbate the inconsistency of earlier training and increase the pressures that have caused the problem in the first place.

Training is most rapid and consistent and training-related stress is minimized when training practices exactly match an animal’s mental abilities. This is evident in the results of great scientific animal trainers such as Marian Bailey, a student of Skinner, and those largely responsible for the tremendous advances in training cetaceans, pinnipeds and canids. The International Society of Equitation Science (ISES, www.equitationscience.com) has proposed eight principles as a means of identifying horse-training systems that align with what we know about learning theory as well as encouraging those who do not to employ them. The application of these principles is not restricted to any single method of horse-training, and ISES does not expect that just one system will emerge. There are many possible systems of optimal horse-training that adhere to all of these principles.

2 To avoid confusion, train signals that are easy to discriminate

From the horse’s viewpoint, overlapping signal sites can be very confusing, so it is essential that signals are applied consistently in areas that are as isolated and separate from one another as possible.

3 Train and shape responses one-at-a-time (again, to avoid confusion)

It is a prerequisite for effective learning that responses are trained one-at-a-time.

6 Train persistence of responses (self-carriage)

The horse should not be subjected to continuing signals from leg (spur) or rein pressure.

8 Benchmark relaxation (to ensure the absence of conflict)

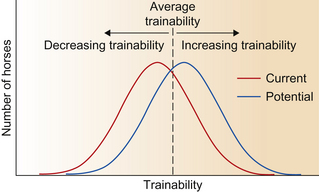

In the normal distribution curve that constitutes the components of what is termed ‘trainability’, the range of horses that are ‘good’, ‘eager-to-please’ and in fact easy to train in the ad hoc systems that comprise contemporary training, occupy a relatively small portion at the top of the trainability scale (Fig. 13.3). It would seem that this could be significantly increased by introducing a scientific approach to training and management and utilizing the principles of learning theory so that we can expedite training, reduce training-related stress and vastly improve horse–human interactions. Equitation science aims to demystify the training of horses. Furthermore, by exploring best practice in horse training, it complements some of the techniques in behavior modification that appear elsewhere in this book (see Chs 1, 4 and 15). Equitation science has an extremely promising future since arguably it is more humble, global, accessible and accurate, and less denominational, commercial, open to interpretation and misinterpretation than any rigid methodology. It has the potential to be the most enduring of all approaches used to train the horse.

Welfare and wastage

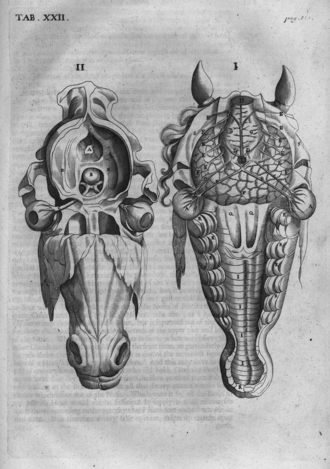

As horse trainers and handlers, our understanding of the horse’s mental abilities is based largely on a centuries-old tradition of horsemanship. Horse-training textbooks (including pony club texts) throughout the world take their reference from traditional horse practice or from the ‘great masters’ of horsemanship who lived in the past 500 years. Such texts generally abound with words to describe horse behavior that imply reasoning abilities (Fig. 13.4). They generally assume that the horse ‘understands’ his training rather than simply responding through reinforcement. Training a horse within the traditional anthropomorphic framework has a number of potentially negative implications for horse welfare, as well as for the safety of riders and handlers. For example, if you believe that a horse complying with your commands is showing a willingness to please you, then you may also believe that when the same horse fails to comply he is actively seeking to displease, defy, undermine and even embarrass you. This belief system explains why so many riders feel justified in physically punishing horses for failure to perform. So while a coach may instruct a child to whip her pony as a punishment when it fails to jump a fence, an equitation scientist primarily sees the lack of response as evidence of pain or a training deficit. A scientific approach acknowledges that lack of forward movement over the fence is but one of myriad other responses that the pony failed to offer, and that whipping after the error is not going to help the pony identify the correct response in the future. [We offer this specific example, not least because this issue of children whipping horses is emerging as an important topic in animal welfare debates that are being informed by equitation science.]

Training does not always go according to plan. Some horses are predisposed genetically to trial undesirable responses rather than desirable ones. Some horses learn to evade stimuli most effectively when the stimuli are predictable by association, e.g. in a schooling context. Horses that have been subjected to inconsistent signals, such as the lack of release of pressure, or to the pain of bad schooling, often acquire the reputation of being difficult and are sold on to homes where more often than not the harshness of schooling is escalated. This contributes to disturbing slaughter statistics. For example, in a French study of more than 3000 non-racing horses, some 66.4% died aged between 2 and 7 years.8 Unlike data from the racing industry,9,10 this wastage was not attributed to orthopedic or respiratory disease but more likely to inappropriate behavior. The welfare implications of this wastage suggest that veterinarians and equine scientists should become well versed in learning theory since it is the basis of good training, continuing education and behavior modification. The wrong approach to training can have consequences far worse than simple time-wasting.

The emotiveness in the horse-riding welfare debate has fostered empirical research into the ethics of equitation and an analysis of some of the more unorthodox interventions that arise during handling, training and competition. According to Derkensen and Clayton,12

The relevance of learning theory

The assumption that the horse is a willing partner and that the aim in coaching is largely to train the rider’s biomechanics to merge into those of the horse is widely accepted in dressage circles. While it is not disputed that, after the consolidation of operant responses, this ideology plays some part in the later development of horse training, the overall approach neglects trial-and-error learning (operant conditioning). Problems arise when equestrian methodologies focus on classical conditioning before or instead of the more deeply ingrained pressure-release responses through trial-and-error learning. This is because confusion (and therefore conflict) often arises in horses unless the basic responses have been installed thoroughly in the first place by trial-and-error learning through negative reinforcement. The fundamental trial-and-error responses under-saddle comprise stimulus control of acceleration and deceleration in gait, limb tempo and stride length, turns of the forequarters from each rein and turns of the hindquarters responses from the rider’s legs. Training the horse by simple cue associations neither ensures controllability in all environmental contexts, nor provides the range of responses that is required for ultimate control in the Olympic equestrian disciplines of show-jumping, horse-trials or dressage. Furthermore, the randomness in behavioral response that horses are able to exhibit when not under complete handler/rider control results in inconsistent stimulus–response relationships which frequently cause chronic stress.16 It is assumed that the prevalence of such methodologies has arisen in the absence of a logical framework based on learning theory.

The cognitive revolution of the 1970s rejected behaviorism. Its legacy is the ‘tendency to underestimate the power of Skinnerian conditioning to shape the behavioral competence of organisms into highly adaptive and discerning structures’.11 This probably contributed to the resistance to the understanding of learning theory in those domains within animal training where it had not already been accepted. Indeed, many texts on equine behavior seem to imply subjective mental experiences in horses.13–15 It would be a scientific error to assume the existence of abilities in the absence of data. Even if there are no data supporting the negative or affirmative case, assuming subjective mental experiences in animals would constitute an unacceptable rejection of the null hypothesis.11 Moreover, most of the published peer-reviewed data strongly indicate that horses lack insight into their instinctive behaviors. As we shall see in the discussion of equine mentality that follows, there are strong selective pressures for this lack of insight to occur.

Horse whisperers

It should be acknowledged that, when trainers apply the principles of learning theory, they generally achieve desirable results. Throughout history, there have been riders who were adept at putting learning principles into practice, but who did not have the advantage of a theoretical basis. They were considered ‘natural horsemen’. Biographies of gifted riders repeatedly suggest that they were at a loss to explain their talents. Unfortunately, this has led to the myth of horse whispering and the mistaken belief that training is more art than science. This set of beliefs has led to a consequent denial of the benefits of applying structured behavioral principles to horse training.

Sometimes the horse-whispering myth provides an irresistible superhuman kudos to the practitioner. But perhaps the greatest limitation of many horse-whispering systems is that training practices are once again locked into method without the illuminations and extrapolations provided by learning theory. Their techniques have arisen from the historical trials of practical horsemanship. Furthermore, the paranormal mystique that surrounds horse whispering and the tremendous variety of techniques tend to confound any search for a unifying principle. Thus horse whispering is often applied without the sort of paradigm shift in thinking about the cause of the problems that we have seen in the behavior modification of other domestic species such as dogs. For this reason much of the current wave of ‘new age’ horse training remains within an anthropocentric and anthropomorphic framework. This is unfortunate because any assumption that the horse is motivated by anything other than its instinctual drives adds an unnecessary layer of complexity to its training. Anthropomorphic explanations of how compliant horses ‘understand’ and ‘oblige’ us are unhelpful for at least two reasons: first, they mystify the training process for novice riders; and second, they imply that non-compliant horses are somehow malevolent. This explains why in one text of equine behavior modification, some horses have even been described as ‘depraved’.18

For example, some practitioners insist that horses in roundpens signal to their human trainers as they would to high-ranking herdmates, and further that they are motivated to be with those humans simply because they ‘respect’ them. In contrast, it is possible that horses in roundpens are showing distance-reducing affiliative signals that are being misinterpreted.18 However, recent empirical studies suggest that the responses of horses to humans in confined areas, such as roundpens, are context-specific19 and may rely more on negative reinforcement than on innate equine social strategies.20 These findings prompt scientists to question the interpretations of horse responses to roundpen interventions commonly offered by some practitioners and offer more scientific, measurable interpretations in horse handling and training.

Finally, a note about the increase in the popularity of roundpens that has resulted from the global interest in ‘whispering’ and relies on an understanding of the flight zone of an animal. A tame animal has a flight distance of zero. Animals are acutely aware of this zone of safety around them so that when it is breached, they move away. In a roundpen situation the horse stops moving when the trainer retreats from the flight zone (Fig. 13.5). It seems that there is sometimes a perceived notion that creating an emotional crisis during roundpen training is actually desirable, probably because it forces the horse to offer a change in ‘attitude’ after which it accepts the human as ‘leader’. The simplest explanation of this change is that the horse’s running away in the roundpen does not increase the distance between it and the human, thus allowing the trainer to use actions and postures to reinforce slowing and shape the horse to approach. Similarly, the practice of lungeing (see Glossary) hyper-reactive horses before training can be seen as problematic as it is often little more than an opportunity for the horse to learn and practice flight-related behaviors.

Figure 13.5 Round-pen work relies on an appreciation of the horse’s flight zone.

(Photograph courtesy of Portland Jones.)

We must exercise caution before advocating approaches to equine training that involve chasing horses and causing them to associate fear responses with any human interactions, because we now know that fear responses and associations are not as prone to extinction as other learned responses.21 The horse may well learn to approach humans, but the means does not justify the end, because, if Le Doux’s findings are to be given any credence, the experience of being chased can leave the horse with a more ‘hair trigger’ flight response. The danger is in the retention of flight-response associations, and its translocation to other interactions with humans. The implications for rider safety are profound.

The problems with contemporary training

By tailoring training strategies to the species’ mental ability, we can increase the efficiency of training and minimize misunderstandings in human–animal interactions. For example, when humans have expectations that animals ‘understand’ what is required, they often give inappropriate signals to the animals (such as delayed, inconsistent or meaningless reinforcements) that result in deleterious behavioral changes.22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree