Angela M. Pelzel-McCluskey, Josie L. Traub-Dargatz

Equine Piroplasmosis

Equine piroplasmosis (EP), also referred to as babesiosis, is an apicomplexan hemoprotozoan-caused disease that affects horses, donkeys, mules, and zebras. The causative agents are Theileria equi (formerly called Babesia equi) and Babesia caballi. Dual infection with both organisms has been reported in equids. Babesia caballi and T equi are protozoan organisms and are obligate intracellular parasites of blood cells. Equids are natural hosts of B caballi and T equi, and certain species of ticks are biologic vectors. Ticks become infected through ingestion of gametocyte-containing erythrocytes (red blood cells) while taking a blood meal from an infected host. In the ticks’ digestive tracts, the gametocytes develop into gametes, which fuse to form zygotes. Babesia caballi zygotes multiply and invade numerous tissues and organs of the ticks, including the ovaries, but not, initially, the salivary glands. Babesia caballi infection can be passed transovarially to the next tick generation, and development to an infective stage for equids occurs in the salivary glands of immature and adult ticks. In contrast, T equi zygotes develop into kinetes, which invade the ticks’ hemolymph and salivary gland cells. Recently, Amblyomma cajennense, a tick with natural range within southern Texas in the United States, was observed to efficiently transmit T equi. Other tick species present in the United States that have been determined to be competent vectors for T equi include Dermacentor variabilis, which is established throughout the southeastern United States, and Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus, a species only present within a permanent quarantine zone between south Texas and Mexico. Tick species in the United States that are competent vectors for B caballi include Dermacentor variabilis, Dermacentor albopictus (which is found throughout the United States), and Dermacentor (Anocentor) nitens (which is found only sporadically in tropical portions of the southern United States). The transovarial transmission of B caballi within Dermacentor (Anocentor) nitens is epidemiologically significant in that such ticks are an additional reservoir for transmission, in addition to the persistently infected horse.

These pathogens can also be mechanically transmitted by use of improperly disinfected needles, syringes, or surgical instruments or through blood transfusion from an infected donor horse to the recipient horse. Vertical transmission of T equi has been documented and reported to result in abortion and neonatal infections that persist for life, but this route of transmission appears to occur infrequently.

Geographic Distribution, United States Importation, and Reporting Requirements

The United States is currently considered to be free of EP except in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands; however, isolated outbreaks of the disease have occurred infrequently in the continental United States. Likewise, EP is not endemic to Australia, Canada, England, Iceland, Ireland, and Japan; however, the disease is found in Africa, the Caribbean, Central and South America, the Middle East, and Eastern and Southern Europe. The increasingly international nature of the horse industry presents potential risks for the introduction of EP from foreign countries. Many areas of the United States have climates suitable for foreign ticks to act as vectors for disease or for native ticks known to be competent transmitters to act as vectors. Because EP is not endemic, most U.S. horses are highly susceptible to acute forms of the disease.

The United States requires that horses being imported from most countries be negative for antibodies against B caballi and T equi before being eligible for release from import quarantine facilities. The testing for importation is conducted at the USDA-APHIS-VS National Veterinary Services Laboratories (NVSL). Before August 2005, the official test for importation purposes was the complement fixation test (CFT). Because the CFT had relatively low sensitivity for detection of chronic carriers, the official test method was changed to the competitive inhibition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (cELISA).

Equine piroplasmosis is considered a foreign animal disease in the United States, and suspected or confirmed cases must be reported to state and federal animal health officials. An official regulatory response will be initiated.

Clinical Signs

Peracute and acute signs may include fever, jaundice, anemia, hemoglobinuria, bilirubinuria, digestive or respiratory signs, and occasionally death. Equids with subacute piroplasmosis may have anorexia, lethargy, weight loss, anemia, limb edema, poor performance, increased heart and respiratory rates, and splenomegaly. Chronic piroplasmosis is clinically indistinguishable from other chronic inflammatory diseases and generally presents with nonspecific signs, such as inappetence, poor body condition, and poor performance. It is important to recognize that many chronic carriers may show no clinical abnormalities at all, appearing clinically and hematologically normal. Anemia may be minimal or absent in equids with chronic infection; these animals are termed carriers and are reservoirs for tick-borne and iatrogenic transmission. Once a horse is infected with B caballi or T equi, the infection in the horse persists unless some type of effective chemotherapeutic intervention is administered.

Babesia caballi and T equi infections cannot be distinguished clinically, and because the clinical signs of EP are variable and nonspecific, diagnostic testing is required to confirm the infection. Differential diagnoses include equine infectious anemia, idiopathic immune-mediated hemolytic anemia, immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, purpura hemorrhagica, plant and chemical intoxication, and reaction to previously administered drugs.

Diagnosis

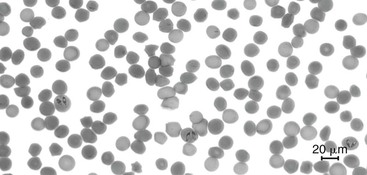

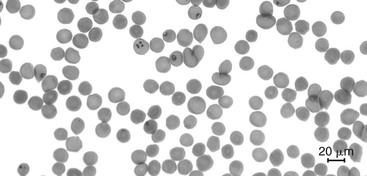

In horses with acute clinical signs consistent with EP, examination of blood smears can assist in diagnosis. Giemsa staining of blood smears followed by careful microscopic examination can reveal intraerythrocytic parasites in acute cases. Babesia caballi can appear pyriform shaped and occurs in pairs (Figure 114-1). Theileria equi appears as four pyriform parasites in a Maltese-cross formation (Figure 114-2). Because the level of parasitemia can be very low in horses that have recovered from clinical disease, examination of the blood smear may not allow for detection of infection in chronic carriers.

To confirm the diagnosis in clinical cases and in chronic carriers, serologic testing is performed. Several types of serologic tests are available for detection of antibodies against B caballi and T equi. These include the CFT, the cELISA test, and the indirect immunofluorescent antibody test. The cELISA tests are available as kits, one kit for B caballi and one for T equi antibody detection. These kits are licensed by the USDA-APHIS-VS Centers for Veterinary Biologics and are available for use at laboratories approved by USDA-APHIS-VS NVSL to perform cELISA testing in certain circumstances.

In an outbreak situation, it may be necessary to perform both the CFT and cELISA tests to detect infection on the basis of stage of infection in a given horse. The CFT is more likely to detect horses in the acute stage of disease, whereas the cELISA is more likely to detect horses with more chronic infection. The samples from horses in the United States with clinical signs consistent with EP are to be submitted to the USDA-APHIS-VS NVSL in Ames, IA, for testing.

Some non-APHIS laboratories have been approved to conduct the cELISA on nonclinical equids for interstate or intrastate movement and for export of equids to countries that do not require NVSL to conduct the testing and do not require any test other than the cELISA. A list of approved laboratories is available at the NVSL website.

Several types of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for detection of the parasite have been developed and are used for research purposes. What role the PCR test will have in determining a horse’s official infection status for regulatory purposes is still being determined.