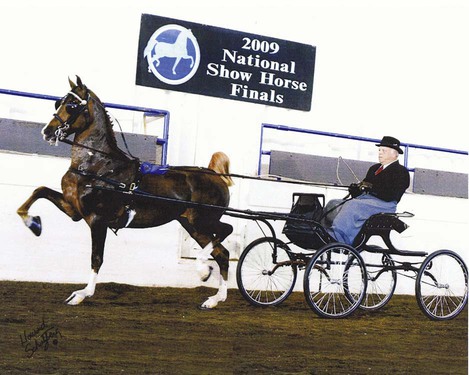

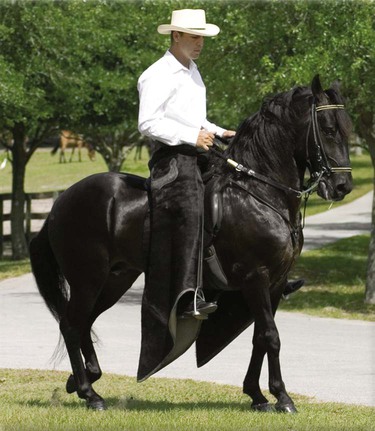

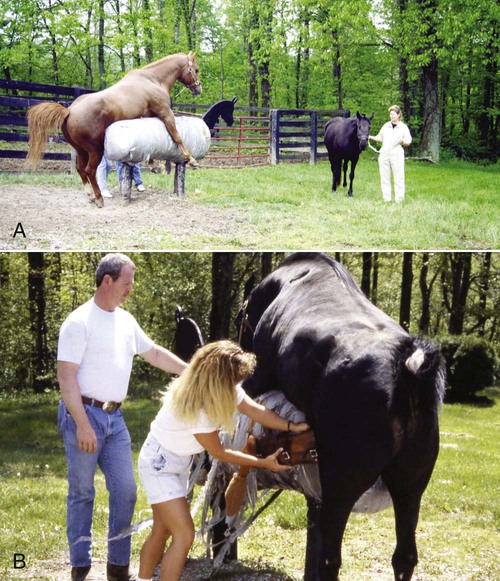

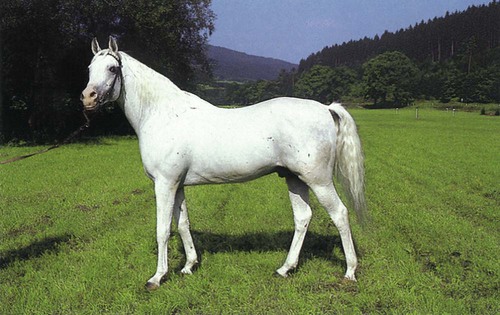

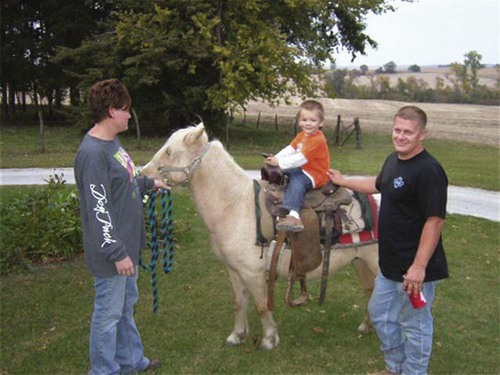

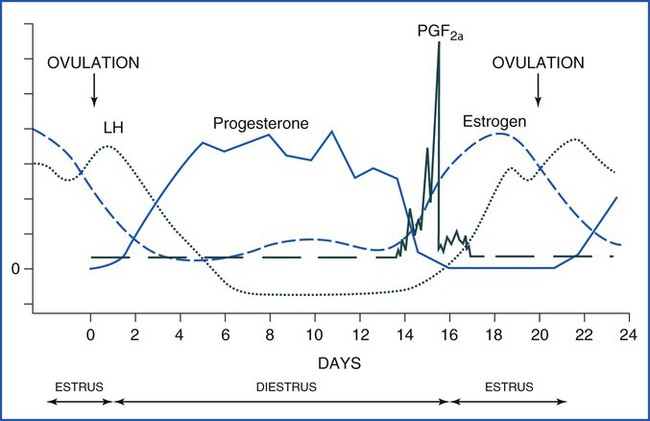

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to • Describe the zoologic classification of the species • Proficiently use terminology associated with this species • List normal physiologic data for the species and be able to identify abnormal data • Identify and know the uses of common instruments relevant to the species • Describe prominent anatomical or physiologic properties of the species • Identify and describe characteristics of common breeds • Describe normal living environments and husbandry needs of the species • Describe specific reproductive practices of the species The Brabant is also known as the Belgian Heavy Draft horse. Its principal breeding area began around Brabant, Belgium. The Brabant is a massive, powerful horse about 16.2hh (hands high) to 17hh. It is short backed and compact. It has very strong, short, sturdily built legs, with ample feathering. The head is small in proportion, square and plain, but the expression is intelligent. The breed is notable for its kind temperament (Fig. 6-3). The Clydesdale originated in the Clyde Valley, Scotland. The breed typically stands around 16.2hh, although some are larger and can weigh up to a ton. The legs often appear long and have abundant silky feathering. The joints should be big, the hocks broad and clean, knees flat, and neck long. Cow hocks are a breed characteristic and are not viewed as a fault. Colors are usually bay or brown, but grays, roans, and blacks are also found. Leg and facial markings are common in this breed (Fig. 6-4). The Percheron originated in the Perche region of Normandy. The horse on average stands 16.2hh. The body is broad and deep chested. The head is pleasing, with a broad square forehead, straight profile, and large mobile ears. The neck is long and arched in the top line. The withers are more prominent than in most heavy breeds and allow for considerable slope in the shoulders, which is reflected in their free-moving action. The legs are short and powerful. The hooves are hard, blue horn, with little feathering on the lower limbs. The usual colors are dappled gray or black, but occasional bay, chestnut, and roan are also accepted (Fig. 6-5). The traditional centers of breeding for the Shire horse are the English counties of Leicestershire, Staffordshire, and Derbyshire, and the Fen country of Lincolnshire. The Shire typically stands over 17hh tall. It is one of the biggest horses in the world and weighs more than a ton. Its neck is relatively long for a draft horse. It runs into deep oblique shoulders, which are wide enough to carry a collar. The legs are clean, hard, and muscular. The hocks should be broad and flat and set at the correct angle for optimum leverage. The hooves should be open; they should be wide across the coronet and have plenty of length in the pasterns. The lower legs carry heavy but straight and silky feathering. Black with white feathering is still the most popular coat color, but numerous gray teams are seen, and bay and brown are also acceptable (Fig. 6-6). The Suffolk Punch developed in East Anglian county. Every Suffolk can trace its descent to a single stallion, Thomas Crisp’s Horse of Ufford. The average height for a Suffolk is 16hh to 16.3hh. Its gaits are distinctive. The hindlegs must be close together, and cow hocks are rarely found. The quarters are huge, rounded, and powerfully muscled. The breed has a strongly crested neck, and the forearms are very muscular with good bone and minimal feathers. All Suffolks are “chestnut.” The Suffolk Horse Society, formed in 1877, recognizes seven shades, ranging from a pale, almost oatmeal color to a dark, almost brown shade. The most usual is a bright, reddish color (Fig. 6-7). Each Paint horse has a particular combination of white and any color of the equine spectrum: black, bay, brown, chestnut, dun, grullo, sorrel, palomino, buckskin, gray, or roan. Markings can be any shape or size and located virtually anywhere on the Paint’s body. Although Paints come in a variety of colors with different markings, there are only three specific coat patterns: overo, tobiano, and tovero. Horses of this breed can be registered in the American Paint Horse Association (APHA). The APHA is the second largest breed association in the United States (Figs. 6-8 to 6-10). Andalusian horse breeding is still centered in the province of Andalusia in southern Spain. The average height for an Andalusian is 15.2hh. The horse has a commanding presence with lofty and spectacular paces. The facial profile is convex, and the eyes are almond shaped. It has a natural balance and a rather sloped croup (Fig. 6-11). The name Appaloosa comes from the breed’s point of origin in the Palouse region covering parts of Washington and Idaho. The Appaloosas are known for their distinctive color, intelligence, and even temperament. Four identifiable characteristics are coat pattern, mottled skin, white sclera, and striped hooves. In order to receive regular registration, a horse must have a recognizable coat pattern or mottled skin and one other characteristic. The seven basic coat patterns are blanket, blanket with spots, roan, roan blanket, roan blanket with spots, spots, and solid. Appaloosas that meet these requirements can be registered with the Appaloosa Horse Club (ApHC) (Fig. 6-12). The origin of the Arabian is unclear, but there is evidence that it existed on the Arabian Peninsula around 2500 bc and was maintained there in its pure form. The body is compact, the back is short and slightly concave, and the croup is long and level. The legs are long, slender, hard, and clean, and the tendons are clearly defined. The head tapers to a very small muzzle with large flared nostrils. The mane and tail hair are fine and silky. During movement the tail is carried arched and high. A dished forehead is common in the breed (Fig. 6-13). The Cleveland Bay (CB) horse is one of the oldest native breeds of England originating in the northern regions. Cleveland Bays are classified as a light draught breed, not “warm blood,” although it is thought that there is no draught blood in the purebreds. They are primarily known for their solid bay color, large ears, blue/black hooves, clean legs, and their calm, kind personality. The Cleveland Bay Horse Society (CBHS) in the United Kingdom maintains a closed stud book for purebreds. An upgrading program exists, but entries are rare. Until 2005, purebreds in the main studbook were limited to a solid bay color, but a very small star was allowed. Current rules accept purebreds with “excessive” white, slight roaning, and chestnuts (which remain very rare), but they are listed as mismarked on registration papers. Fewer than 1000 purebreds exist worldwide, with about 180 in North America. Cleveland Bay crosses, often referred as “partbreds” or “sport horses,” are sometimes misidentified as purebreds. This is an indication of the strong influence the breed has on other breeds when crossed. Separate registries for crosses are maintained by the CBHS and CBHS Australasia (Fig. 6-14). The Hackney derives from the famous trotting “Roadsters” of Norfolk and, to a lesser extent, the Yorkshire Roadsters, which shared a common ancestry with the Norfolk breed. The Hackney typically stands between 14hh and 15.3hh. The hocks are set closely to the ground, the shoulders are exceptionally strong, and the withers are low. The Hackney pony shares the same stud book but is truly a pony. It stands up to 14hh but shares the same characteristics found in the Hackney horse (Fig. 6-15). The Missouri Fox Trotter originated with the settlers from Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia who made their home in the Ozark Hills of Missouri. The body is well muscled, fairly deep, and noticeably wide. Although usually sufficiently compact, it may have some length in the back. The chest is wide and deep. The shoulders are strong, and the breed has rounded withers. The breed stands on average between 14hh and 16hh tall. The predominant coloration is chestnut in all shades, usually with white markings, although any color is accepted (Fig. 6-16). The Morgan horse gained its name from one phenomenal stallion named Figure, who later became known as Justin Morgan, after a former owner. The breed is regarded as the first American Breed, with Figure’s birthplace believed to Springfield, Massachusetts. The present-day Morgan stands between 14.1hh and 15.2hh. The Morgan is easily recognized by his proud carriage, upright graceful neck, and distinctive head with expressive eyes. Deep bodied and compact, the Morgan has strongly muscled quarters. The intelligence, willingness, zest for life, and good sense of the Morgan are blended with soundness of limb, athleticism, and stamina. Morgans can be registered with the American Morgan Horse Association (AMHA) (Fig. 6-17). The Tennessee Walking horse evolved in the state of Tennessee in the mid-19th century. The breed is deep bodied and short-coupled, with a head that tends to be rather plain. It carries its head much lower than a Saddlebred, and the horse moves with far less elevated action. The breed stands between 15–16hh. Predominant colors are black and all shades of chestnut, sometimes with prominent white markings (Fig. 6-19). The American Saddlebred originated in the American South and was initially called the Kentucky Saddler. The principal breeding area is still the Kentucky’s Bluegrass Country around Lexington. The horse typically stands around 16hh. The quarters are smoothly muscled with a near-level croup and a high-set tail. The hindlegs despite length in the shanks, are well formed, with long musculature, clean hocks, and flat, hard fetlock joints. The neck is long and elegant; its juncture with the withers ensures a distinctively high carriage in movement. The head is neat and fine with no fleshiness through the jowl (Fig. 6-20). The American Standardbred was first established in the eastern states of the United States. Its body is long and low but is still powerful and deep through the girth. The overall build is powerful. The croup usually is higher than the wither to give enormous propulsive thrust to the quarters. It has strong forearms. The head is plain but not unattractive. It is, however, heavier and less refined than that of the Thoroughbred (Fig. 6-21). The Thoroughbred first evolved in England during the 17th and 18th centuries. The body is typically long in its proportions. The quarters and the loins are strong. The hindlegs are long. The forearms are fine, long, and muscular. The head is refined and alert with no hint of fleshiness in the jowl. It blends into a long, gracefully arched neck that in turn joins symmetrically with the shoulders. The shoulders are long and very well sloped with prominent withers (Fig. 6-22). The Quarter horse originated in the United States during the colonial era and was developed for racing the quarter mile. The breed has a refined head with a straight profile that is distinctively shorter and wider than that of the Thoroughbred. They usually stand between 14hh and 16hh. The horses are compact and well muscled. The underline is longer than the back. The quarters are muscular. Horses of the breed can be registered with the American Quarter Horse Association (AQHA). The Quarter horse is one of the most popular breeds in the United States and has the largest breed registry in the world (Fig. 6-23). The Palomino cannot be granted true breed status because of the variations in size and appearance. Therefore, it is classified more as a color than a breed; however, horses can be registered in the Palomino Horse Association, Inc. (Fig. 6-24). The breed originated from the efforts of one man, Leslie Boomhower of Mason City, Iowa. The breed standard calls for a pony that had the appearance of a miniature Quarter Horse/Arabian cross, with Appaloosa coloring and some of that breed’s features. They usually are between 11.2hh and 13.2hh tall. All of the ponies are inspected before full registration is issued to ensure that they meet the breed specification. Emphasis is given to substance, refinement, and a stylish straight, balanced action marked by notable engagement of the hocks under the body (Fig. 6-26). The breeding of the American Shetland pony was originally centered in the state of Indiana, following the large importations of ponies from the Scottish Shetland Islands that began in 1885. The pony typically stands up to 11.2hh. The withers are unusually prominent for a pony and contribute to the slope of the shoulder. The girth is a good depth and the legs are longer than in other ponies (Fig. 6-27). Welsh ponies belong firmly to the Principality of Wales. For centuries they have been bred on the hills and uplands. The Welsh pony can be classified into four sections—A, B, C, and D—with A being the smallest and D being the tallest. Ponies across all four sections can vary in height from 12hh to 15hh. The Ponies stud book is located with the Cob stud book. The pony has a flowing outline that is symmetrical and balanced in its proportions. It is full of quality and pony character. The forelimbs are long and well-muscled. The head shows Arabian influence (Fig. 6-28). Many of the miniature horses have several breed influences, but the Falabella is one of the main influences founded in South America. The miniature horse cannot exceed 34 inches in height measured from the last hairs of the mane. The breed should be small, sound, and well balanced and should have correct conformation. Refinement and femininity should be seen in the mare. Boldness and masculinity should be seen in the stallion; the general impression should be one of symmetry, strength, agility, and alertness. Horses of this breed can be registered with the American Miniature Horse Association (AMHA) (Fig. 6-29). The donkey or ass is domesticated member of the Equidae family. A male donkey is called a jack. A female donkey is called a jenny (Fig. 6-30). A mule is a cross between a male donkey and a female horse. A hinny is a cross between a female donkey and a male horse. Almost all mules and hinnies are infertile and unable to reproduce. A female mule that has an estrous cycle is called a molly. A molly can occur naturally or can be accomplished through hormone manipulation. Mollies have short thick heads with long ears and come in a variety of colors (Fig. 6-31). The normal reproductive course for any large animal species is discussed in Chapter 3. Table 6-1 lists specific equine breeding information. The following reproductive procedures are variations that exist among species. Figure 6-32 illustrates the equine estrous cycle. TABLE 6-1 • Successful breeding: Mares do not always readily accept the male. Also, timing of insemination (natural or artificial) must correspond to the time of ovulation, which may be difficult to determine. The source of the semen (the stallion) may not be at the same location as the female, requiring that the semen be shipped to the mare or that the mare be shipped to the stallion’s farm for breeding. • Successful implantation: The period from conception to implantation is prolonged in horses; implantation begins approximately on day 35. Embryonic losses are high during the time before implantation. • Successful gestation: Gestation in the horse averages 330 to 345 days. • Successful parturition: The placenta begins to separate early during the delivery process; deprived of this oxygen source, foals rarely survive dystocias that last more than 1 hour. • The foal must still survive the delicate neonatal period. Veterinary medicine is often involved in each of the earlier steps. Coupled with the economics of the breeding industry, breeding mares can be a tricky and expensive business. Performing a uterine culture can confirm the presence or absence of uterine infection (Box 6-3). Sensitivity testing can also be performed to guide proper antibiotic therapy. Some breeders culture mares routinely at the beginning of the breeding season so that early treatment of “dirty” mares can be pursued. Infusion is a method of delivering liquids into the uterus (Box 6-4). Indications for the procedure include the following: • Treatment of uterine infection, in which antibiotics are diluted in a sterile solution (e.g., sterile saline or lactated Ringer’s solution) and infused into the uterus; this can be repeated daily for several days • Routine flushing (lavage) of the uterus after an abortion or after foaling • “Postbreeding” infusion to prepare the uterus to receive an embryo Biopsy of the lining of the uterus is done to evaluate the histologic condition of the endometrium, usually as part of an assessment of a mare’s fertility (Box 6-5). The endometrium contains the endometrial glands, which support and nourish the embryo. The endometrium is also the site for implantation and development of the placenta. Uterine infections, trauma from foaling, and aging may cause abnormalities such as atrophy of the endometrial glands, fibrosis around the glands, and inflammation, which can interfere with the mare’s ability to support pregnancy. Biopsy allows a histopathologist to examine the condition of the endometrium and assess the probability of the mare being able to support a pregnancy. The histopathologist usually assigns a grade of 1, 2, or 3 to the specimen, with grade 1 representing a normal or minimally abnormal specimen, grade 2 representing mild to moderate pathology, and grade 3 representing severe or irreversible pathology. The biopsy is obtained with a 70-cm long (≈28 inch) stainless steel uterine biopsy forceps (Fig. 6-33). The forceps should be sterilized. The forceps have alligator jaws and can obtain a tissue sample approximately 1.5 mm long and 4 mm wide. It may be necessary to use a small syringe needle to carefully retrieve the sample from the forceps jaws. Once retrieved, the sample is placed in a liquid fixative. The technician should consult the laboratory for the preferred method of fixation. Common fixatives include Bouin’s fixative, 10% buffered formalin, and 70% alcohol. Samples should not sit in Bouin’s fixative for more than 24 hours. The actual collection procedure is potentially dangerous. Breeding behavior in horses is usually aggressive and sometimes violent, and personnel are in vulnerable positions. Many facilities require personnel to wear helmets. The procedure requires a minimum of one person to handle the mare, one to handle the stallion, and one person to perform the collection into the AV. The usual method is to restrain the mare, then lead the stallion to approach the mare from her left side. The stallion is allowed to mount the mare, and the semen collector quickly moves in to grasp and divert the penis into the AV before it can enter the mare. The hands are then used to stabilize the AV alongside the mare while the stallion ejaculates. The AV is aimed slightly downward so that the ejaculate flows into the collection bottle (Fig. 6-34).

Equine Husbandry

Breeds of Horses

Common Draft Horse Breeds

Brabant

Clydesdale

Percheron

Shire

Suffolk Punch

Common Light Horse Breeds

American Paint

Andalusian

Appaloosa

Arabian

Cleveland Bay

The Hackney and Hackney Pony

Missouri Fox Trotter

Morgan

Tennessee Walking

American Saddlebred

American Standardbred

Thoroughbred

Quarter Horse

Color Associations

Palomino

Common Pony Breeds

Pony of America

American Shetland Pony

Welsh Pony

The Miniature Horse

Miniature Horse

Donkeys and Mules

Reproduction

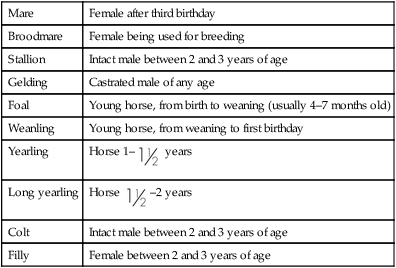

Type of estrous cycle

Seasonally polyestrous (long day breeder)

Age of female at puberty

10–24 months

Age of male at puberty

10–24 months

Time of first breeding

Varies (2–3 years)

Estrous cycle frequency

15–26 days

Duration of estrus

2–12 days (average 5–7)

Time of ovulation

Last 48 hours of estrus

Optimal time of breeding

Every 24–48 hours while the mare is in heat

Gestation period for light breeds

305–365 days

Birth weight

Varies by breed

Litter size

1 (twins are rare and undesirable)

Weaning age

4–7 months

Equine Female Reproductive System

Female Reproductive Examination

Uterine Culture

Uterine Infusion

Endometrial (Uterine) Biopsy

Semen Collection in the Stallion

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Equine Husbandry

years

years –2 years

–2 years