CHAPTER 13 Environmental Skin Diseases

Environmental disorders are common and often a cause of substantial economic loss in equine medicine. In many instances—chemical toxicoses, mycotoxicoses, and hepatotoxic plant toxicoses—the dermatologic abnormalities are clinically spectacular and of important diagnostic significance, but are of less importance prognostically, therapeutically, and financially compared with abnormalities in other organ systems. An in-depth discussion of many of these diseases is beyond the scope of this chapter; therefore, the dermatologic feature of each condition has been emphasized. For detailed clinicopathologic information on many of these disorders, the reader is referred to other textbooks.1,3,6

Mechanical injuries

Intertrigo

Intertrigo is a superficial inflammatory dermatosis that occurs in places where skin is in apposition and is thus subject to the friction of movement, increased local heat, maceration from retained moisture, and irritation from accumulation of debris.5 When these factors are present to a sufficient degree, dissolution of stratum corneum, exudation, and secondary bacterial infection are inevitable.

Intertrigo is occasionally seen in mares.5 Congestion of the udder at parturition is physiologic, but may be sufficiently severe to cause edema of the belly, udder, and teats. In most cases, the edema disappears within 2-3 days after parturition. However, if extensive and persistent, the edema can lead to intertrigo in the intramammary sulcus and where the skin of the udder contacts the skin of the medial thighs. Lesions include oozing, crusting, secondary bacterial and/or yeast infections, and in severe cases, necrosis. A foul odor may be present. The affected areas may or may not be painful.

Diagnosis is based on history, physical examination, and cytology. Treatment includes the daily applications of gentle antiseptic soaps, astringent rinses, and dusting with powders to reduce friction. Secondary bacterial and/or yeast infections are treated appropriately (see Chapters 4 and 5). Healing is usually complete within 3-4 weeks.

Hematoma

A hematoma is a circumscribed area of hemorrhage into the tissues.1,5 It arises from vascular damage associated with sudden, severe, blunt external trauma (e.g., a fall). The lesions are usually acute in onset, subcutaneous, fluctuant, and may or may not be painful. Hematomas are most commonly seen subsequent to fractures, on the vulva subsequent to difficult deliveries, and on the brisket of foals (Fig. 13-1).5

Hygroma

Hygromas are cutaneous swellings associated with an underlying bursitis.1,5 Bursitis may occur after acute or chronic trauma to an existing bursa (e.g., bicipital, cunean, supraspinous, trochanteric) or after the development of an acquired bursa (e.g., capped hock, capped elbow, carpal hygroma). A local, fluctuant swelling develops over the site of injury, with variable edema and pathology of the overlying skin. Therapeutic principles include removing the cause and bandaging. Systemic antiinflammatory agents and/or local injections of glucocorticoids may be indicated. Surgical intervention is usually a last resort.

Pressure Sore

Pressure sores (decubital ulcers) usually occur due to prolonged application of pressure concentrated in a relatively small area of the body and sufficient to compress the capillary circulation, causing tissue damage or frank necrosis.1,5 Tissue anoxia and full-thickness skin loss rapidly progress from a small localized area to produce ulceration, which almost invariably becomes infected with a variety of pathogenic bacteria. Within a matter of 24-48 h, the edges of the ulcerated area become undermined. The ulceration may later extend to underlying bone. Because of the area of capillary and venous congestion in the base of the ulcer and at the tissue margins, systemic antibiotic therapy is virtually useless, except in the case of bacteremia.

Pressure sores (bedsores, saddle sores, saddle galls, girth galls, sit fasts) are caused by prolonged, continuous pressure—often relatively mild—leading to ischemic necrosis.1,5 They are commonly seen in horses, especially in association with ill-fitting tack (Fig. 13-2), ill-fitting bandages and casts (Fig. 13-3), prolonged anesthetic/surgical procedures (Fig. 13-4), and prolonged recumbency. Animals that are emaciated (decreased fat and muscle layers) are at increased risk.

Bite and Kick Injuries

Bites and kicks can result in contusions, hematomas, abscesses, and lacerations.7,8 Though such injuries can occur at any time, pasture encounters are the most common. In addition to chasing, rearing, and mounting, kicking and biting are signs of normal equine behavior and are part of aggressive, threatening, submissive, and avoidance behavior. Not all kick injuries are due to aggression: some occur accidentally with exuberant behavior. Warmbloods, Thoroughbreds, and Arabians had a 4.3 times higher risk of bite or kick injuries.7,8 A stable group hierarchy and a housing system that provides adequate space and is adapted to horse-specific behavior are important factors in prevention.

Foreign Bodies

Foreign bodies occasionally cause skin lesions in horses.*

Cause and pathogenesis

Most commonly, the foreign material is of plant origin, especially wood slivers and the seeds and awns of cheatgrass, needlegrass, poverty grass, crimson clover, and foxtail.5 Other foreign bodies associated with skin lesions in horses include fragments of wire, darts, cactus spines, material from gunshot injuries, and suture material.5,10,11

Because most bullets are pointed, little material is taken in at the entry site, but large amounts of material are sucked in at the exit site, producing widespread contamination.10,11 Suture sinus reactions have been associated with nonabsorbable polyamide, polyester, and polypropylene suture.5 Suture sinuses can be associated with any suture material, but the prevalence is higher following the use of multifilament or braided suture materials.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes infectious and sterile granulomas and abscesses and neoplasia. The definitive diagnosis is based on history (exposure?), physical examination (object palpable?), radiography, ultrasonography, and surgical exploration. Ultrasonography is an excellent imaging technique for detecting various foreign bodies in the skin and muscle of horses.1,5 Histopathologic findings include granulomatous to pyogranulomatous dermatitis and panniculitis, wherein evidence of the foreign material may or may not be found.

Clinical management

The only successful treatment is removal of the foreign material.1,9,10 Systemic antibiotic therapy is often needed for secondary bacterial infection. All gunshot wounds must be treated by debridement and wound excision, and healing is by secondary intention or delayed primary closure 4-5 days after the primary surgery.1,10,11

Myospherulosis

Myospherulosis is an extremely rare granulomatous reaction thought to be due to the interaction of ointments, antibiotics, or endogenous fat with erythrocytes.2,5,12 It is associated with small saclike structures (parent bodies) filled with endobodies (spherules). Myospherulosis is most commonly reported after injection of oily medicaments or after the topical application of oily products to open wounds. Because muscle is not always involved, it has been suggested that spherulocytosis or spherulocytic disease might be a better designation for this entity.

Patients are usually presented for solitary subcutaneous or dermal nodules, which may or may not have draining tracts. Histologic examination reveals several solid and cystic areas.2,12 The walls of the cystic areas and most of the solid areas are composed of histiocytes with abundant vacuolated cytoplasm. Histiocytes surround parent bodies (20-350 µm in diameter) composed of thin eosinophilic walls and filled with homogeneous eosinophilic 3- to 7-µm diameter spherules. Parent bodies and spherules do not stain with periodic acid-Schiff, Gomori methenamine silver, or acid-fast stains, but are positive for endogenous peroxidase (diaminobenzidine reaction) and hemoglobin, indicating that the spherules are erythrocytes. The only effective treatment is surgical excision.

Arteriovenous Fistula

An arteriovenous fistula is a vascular abnormality, defined as a direct communication between an adjacent artery and a vein that bypasses the capillary circulation.1,2,13 Arteriovenous fistulae may be congenital or acquired, and they are extremely rare in horses.13 Congenital fistulae result from abnormal maturation of embryonic vasculature, whereas acquired fistulae usually result from trauma (especially penetrating wounds).

Diagnosis is based on history, physical examination, and demonstration of the fistula by contrast radiography or color-flow Doppler ultrasonography.13 Therapy includes surgical extirpation of the fistula.

Gangrene

Gangrene is a clinical term used to describe severe tissue necrosis and sloughing.1,5 The necrosis may be moist or dry. The pathologic mechanism of gangrene is an occlusion of either arterial or venous blood supply. Moist gangrene is produced by impairment of lymphatic and venous drainage plus infection (putrefaction) and is a complication of pressure sores associated with bony prominences and pressure points in recumbent animals. Moist gangrene presents as swollen, discolored areas with a foul odor and progressive tissue decomposition. Dry gangrene occurs when arterial blood supply is occluded, but venous and lymphatic drainage remain intact and infection is absent (mummification). Dry gangrene assumes a dry, discolored, leathery appearance.

The causes of gangrene include: (1) external pressure—pressure sores, rope galls, constricting bands, ill-fitting tack; (2) internal pressure (severe edema); (3) burns (thermal, chemical, friction, radiation, electrical); (4) frostbite; (5) envenomation (snake bite); (6) vasculitis; (7) ergotism; and (8) various infections (clostridial, staphylococcal) (Fig. 13-5). Gangrene and sloughing of the distal limbs has been described in foals and is thought to be due to hypoxia and dehydration.14 For diagnosis and management of these conditions, the reader is referred to appropriate sections of this book.

Subcutaneous Emphysema

Subcutaneous emphysema is characterized by free gas in the subcutis.1,5

Cause and pathogenesis

It has been described as a sequela to tracheal perforation, esophageal rupture, penetrating wounds (especially in the axillary region), and clostridial cellulitis/myositis.1,5,15,19 Massive subcutaneous emphysema is a sequela to pneumomediastinum, which may also be caused by vigorous abdominal, diaphragmatic, and thoracic muscular contraction against a closed glottis. Air from ruptured pulmonary alveoli then gains access to the perivascular spaces, migrates along the adventitia of blood vessels, and reaches the mediastinum. From these, the air reaches the soft tissues of the neck, face, torso, and extremities via fascial planes, which produces subcutaneous emphysema.

Draining Tracts

Draining tracts are commonly encountered and are usually associated with penetrating wounds that have left infectious agents and/or foreign bodies behind.1,5,18 There is often no known history of a previous injury. Draining tracts may also result from infections of underlying tissues (e.g., bone, joint, lymph node) and previous injections. Pectoral draining tracts have rarely been caused by rib sequestration or thoracic abscess.5,18 Penetrating injuries of the thorax and abdomen are relatively infrequent and often associated with running into a fixed object.19 Possible internal complications include pneumothorax, pleuritis, peritonitis, and bowel eventration.

Open comminuted fractures of the facial bones can lead to the formation of facial fistulae (sinocutaneous fistulae).16,17,20 Injury and loss of skin and bone over sinuses results in full-thickness defects over sinuses. One or more draining tracts may be present. Sinus mucous membrane is seen attached to the skin margins, and air moves through the hole(s) during respiration. H-plasty bipedicle skin and periosteum-flap closure are recommended.17

Diagnosis is confirmed by various combinations of cytology, culture, histopathology, radiography, ultrasonography, and contrast fistulography. Surgical drainage, removal of foreign material, and appropriate treatment of secondary infections are the cornerstones of successful management.1,9

Thermal injuries

Burns

Cause and pathogenesis

Burns are occasionally seen in horses and may be thermal (barn, forest, and brush fires; accidental spillage of hot solutions; firing [Fig. 13-6]), electrical (electrocution; lightning strike), frictional (rope burns [Fig. 13-7]; abrasions from falling), chemical (blisters; improperly used topical medicaments; maliciously applied caustic agents), or radiational (radiotherapy).*

Figure 13-6 Permanent scarring subsequent to severe burns caused by bar firing for “bowed tendons.”

(Courtesy R. Pascoe.)

The cause of the burn and the percentage of body involvement have great impact on the patient’s survival. Patients burned by fire are at great risk for damage to the respiratory tract. Patients with large burns experience fluid and electrolyte imbalances and may die rapidly if not treated appropriately. If 25% of the body is burned, there are usually systemic manifestations (septicemia, shock, renal failure, anemia). Animals with burns over 50% or more of their body usually die. The reader is referred to other sources for in-depth discussions of the pathophysiology of burns and the management of severely burned patients with extracutaneous complications.*

Clinical findings

Burns are most commonly seen over the dorsum and face (Figs. 13-8–13-10). They have been classified according to severity.† First-degree burns involve the superficial epidermis; are characterized by erythema, edema, heat, and pain; and generally heal without complication. Second-degree burns affect the entire epidermis; are characterized by erythema, edema, heat, pain, and vesicles; and usually reepithelialize with proper wound care. Third-degree burns affect the entire epidermis, dermis, and appendages; they are characterized by necrosis, ulceration, anesthesia, and scarring. Diligent therapy and possibly skin grafting are indicated. Fourth-degree burns involve the entire skin, subcutis, and underlying fascia, muscle, and tendon.

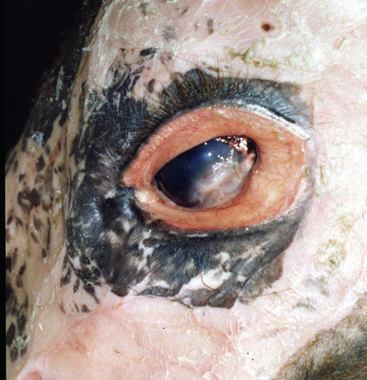

Figure 13-10 Same horse as in Figs. 13-8 and 13-9. Periocular alopecia, erythema, scaling, and damage to eyelids and cornea.

Lightning strike produces virtually pathognomonic skin lesions: linear or arboreal patterns of singed hair and burned-to-charred skin.23 Lesions are most commonly seen on the limbs, flank, and axillary region.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually straightforward and is based on history and physical examination. Histopathologic findings of a gradually tapering coagulation necrosis of the epidermis and deeper tissues are typical of a burn.5 Electrical burns may show a diagnostic histologic feature of a fringe of elongated, degenerated cytoplasmic processes that protrude from the lower end of the detached basal epidermal cells into the space separating the epidermis and the dermis. The nuclei of the basal cells and often of the higher-lying keratinocytes appear stretched in the same direction as the fringe of cytoplasmic processes. This gives the image of keratinocytes that are “standing at attention.”

Clinical management

Care of burn wounds usually includes one or more of the following: (1) thorough cleansing (povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine), (2) surgical debridement, (3) daily hydrotherapy, and (4) topical antibiotics.* Occlusive dressings are avoided because of their tendency to produce a closed wound with bacterial proliferation and to delay healing. The wound should be cleaned two or three times daily, and the topical antibiotic reapplied. The most commonly used topical antibiotic is silver sulfadiazine, a painless, nonstaining, broad-spectrum antibacterial agent with the ability to penetrate eschar. Systemic antibiotics are not effective in preventing local burn wound infections and may permit the growth of resistant organisms. Many burned equine patients are pruritic, and measures must be taken to prevent self-mutilation (drugs, cross-tying, and so forth).

Burns heal slowly and many weeks may be required to allow the wound to close by granulation. Because scarred skin is hairless and often depigmented, solar exposure should be limited. Burn scar neoplasms—squamous cell carcinoma, fibrosarcoma, fibroma, sarcoid—have been reported in horses (see Chapter 16), so the areas should be examined periodically.

Frostbite

Frostbite is an injury to the skin resulting from excessive exposure to cold.2,3,5,6 It is rare in healthy animals who have been acclimatized to the cold. Frostbite is more likely to occur in neonates; animals that are sick, debilitated, or dehydrated; animals having preexisting vascular insufficiency; and animals that have recently moved from a warm climate to a cold one. The lower the temperature, the greater the risk. Lack of shelter, blowing wind, and wetting decrease the amount of exposure time necessary for frostbite to develop.

Frostbite typically affects the tips of the ears, tail tip, teats, scrotum, and feet.5 These areas are often not well-insulated by hair, and the blood vessels are not as well protected. While frozen, the skin appears pale, is hypoesthetic, and is cool to the touch. After thawing, mild cases present with erythema, edema, scaling, and alopecia. Severe cases present with necrosis, dry gangrene, and sloughing.

Primary irritant contact dermatitis

Contact dermatitis is an inflammatory skin reaction caused by direct contact with an offending substance.2,5

Cause and Pathogenesis

Primary irritants have one thing in common: they invariably produce dermatitis if they come into direct contact with the skin in sufficient concentration for a long enough period.2,5 No sensitization is required. Moisture is an important predisposing factor, since it decreases the effectiveness of normal skin barriers and increases the intimacy of contact between the contactant and the skin surface. In this regard, the sweating horse is an ideal candidate for contact dermatitis over any area of the body. The rapidity of onset and the intensity of the reaction depend on the nature of the contactant, its concentration, the duration of the contact, and the preexisting health of the skin. Although most primary irritants are chemicals, similar skin lesions can be produced by thermal injuries, solar damage, and contact with living organisms.

Substances reported to cause primary irritant contact dermatitis include body excretions (feces and urine [Fig. 13-11]), wound secretions, caustic substances (acids and alkalis), crude oil (Figs. 13-12–13-14), diesel fuel, turpentine, leather preservatives, mercurials, various blisters (Fig. 13-15), leg sweats, topical medications (Fig. 13-16), improperly used topical parasiticides (sprays, dips, pour-ons, and wipes [Fig. 13-17]), irritating plants Helenium microcephalum [small-head sneezeweed], Cleome gynandra [prickly spider flower], Urtica ureus and U. dioica [stinging nettle], and Euphorbia spp. [spurge]), wood preservatives, bedding, and a filthy environment.5

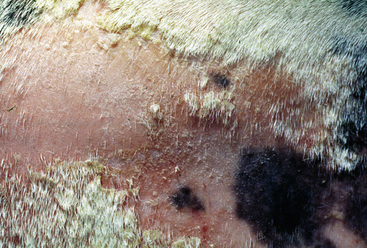

Figure 13-12 Primary irritant contact dermatitis due to application of motor oil. Alopecia, scaling, and erythema over thorax.

Figure 13-15 Primary irritant contact dermatitis on caudal pastern due to application of mustard oil.

(Courtesy W. McMullen.)

Figure 13-16 Contact dermatitis. Alopecia, erythema, crusting, and ulceration due to topical medications.