Chapter 7 Endocrine Diseases

Adrenal Gland Disease

Adrenocortical disease has been recognized for almost 25 years as a common malady affecting pet ferrets both in the United States and in many countries around the world.11,20,25,35,39,53,54,58,68,72,91,93,109 It is typically seen in middle-aged to older ferrets and is most commonly characterized by hair loss in both sexes and by vulvar enlargement in females.35,58,91 Clinical signs of adrenocortical disease in ferrets differ from those of classic Cushing’s disease in dogs; moreover, plasma cortisol concentrations are rarely increased in ferrets. Instead, the concentrations of estradiol, 17-hydroxyprogesterone, or one or more of the plasma androgens may be increased as a result of adrenocortical hyperplasia, adenoma, or adenocarcinoma.93

There has been much speculation regarding the underlying cause of the pathologic changes in the adrenal glands of these ferrets. Suggested causes include early neutering, genetic predisposition, light-dark cycle disruptions, and diet.12,13,42,46,85,97,98 The role of early neutering has garnered the most attention and study. Historically, gonadectomy at an early age in some strains of mice was observed to lead to adrenocortical nodular hyperplasia or neoplasia of one or both adrenal glands. These glands hypersecrete estrogens or androgens.30,70,99 Like mice that undergo gonadectomy early in life, most commercially raised ferrets in the United States undergo ovariohysterectomy or castration before they are 6 weeks of age.

Another possible explanation is not necessarily the age of neutering but the time period between neutering and the onset of disease.97 To this end, gonadotrophic hormones appear to play a role in the pathogenesis of hyperadrenocorticism in ferrets.98 Specifically, this condition has been defined as a disease resulting from the expression of luteinizing hormone (LH) receptors on adrenocortical cells that produce sex steroids. The speculative pathogenesis is that, after neutering, LH and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) persistently stimulate the adrenal cortices as a result of the loss of negative gonadal feedback on hypothalamic gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH), resulting in adrenocortical hyperplasia. To further support this hypothesis, LH receptors that could trigger abnormal adrenal gland growth have been found in the adrenal glands of normal ferrets.97 In a small study of adult ferrets, there was a high incidence of adrenal gland disease during a 1- to 7-year period after surgery.42 These results may be further evidence that adrenal gland disease is influenced more by lack of negative feedback than the practice of early neutering.12 As the ability to study disease at the molecular level becomes more robust, the underlying pathogenicity of adrenal gland disease in ferrets will become more evident.77

Other possible causes of adrenal gland disease in ferrets may be related to husbandry. One speculated risk factor for adrenal gland disease is the artificial light:dark cycle to which indoor ferrets are exposed.46,69,85 The long light cycle, as would be present with ferrets living indoors, stimulates the release of GnRH and LH while simultaneously inhibiting the production of melatonin. The increased LH concentrations combined with decreased circulating melatonin (a known antigonadotropic hormone) stimulate receptors in adrenal gland tissue, leading to adrenal gland disease.85 Therefore housing ferrets indoors may be a contributing risk factor to the pathogenesis of adrenal gland disease.69,85

History and Physical Examination

In at least one study, most ferrets reported with adrenocortical disease were female.91 Many owners are aware that an enlarged vulva in a female ferret is a cause for concern. The vulva enlarges normally during estrus, and many owners know that prolonged estrus can result in estrogen-induced bone marrow toxicosis. Thus although the disease is reported more frequently in females than in males, this may be caused by a presentation bias rather than an actual sex predilection and may not reflect the true incidence of disease.11

In one study, the average age at which signs of adrenal disease were first observed by ferret owners was approximately 3.5 years.91 A smaller study has reported an older age distribution for this disease.72

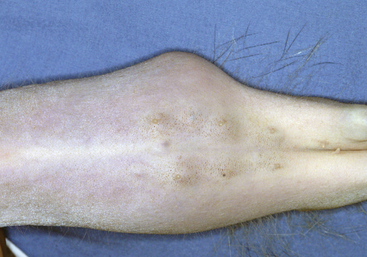

Alopecia is the most common clinical manifestation of adrenocortical disease and develops in both male and female ferrets (Fig. 7-1). More than 90% of ferrets with adrenal gland disease have some hair loss. The hair epilates easily. Alopecia is usually symmetrical, beginning on the rump, the tail, or the flanks and progressing to the lateral trunk, dorsum, and ventrum. These patterns of alopecia should be documented in the medical record for comparison as the disease progresses.

More than 70% of female ferrets with adrenal gland disease have an enlarged vulva (Fig. 7-2).91 The vulva can be slightly to grossly enlarged and become turgid and edematous, resembling the vulva of a jill in estrus. A seromucoid discharge may be present, and results of cytologic examination may show localized vaginitis. The perivulvar skin may appear dark and bruised.

Partial or complete urinary blockage in male ferrets is occasionally associated with adrenocortical disease.20,88 Affected ferrets have dysuria or stranguria. Periurethral cysts develop in the region of the prostate (possibly originating from hormone-responsive cells) and cause urethral narrowing. Because of the urethral narrowing, passing a urinary catheter into the bladder of these ferrets can be difficult (see Chapter 2). A ferret with a urethral blockage may have a life-threatening metabolic derangement; therefore these cases usually constitute emergencies. In some ferrets, removing the diseased adrenal tissue and draining the cysts resolves the urinary blockage within 1 or 2 days. In others, the prostatic tissue is infected and aggressive surgical treatment along with antibiotic and hormonal therapy is necessary (see Chapter 11).

On physical examination, enlarged adrenal glands are sometimes palpable (Fig. 7-3). The left adrenal gland is more easily identified than the right. The left gland is usually engulfed in a large fat pad cranial to the left kidney. It may feel like a small, firm, round mass. Because the right gland has a more cranial location and is under a lobe of the liver, it is more difficult to palpate. Enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes may be palpable.

The spleen may be palpably enlarged, but it usually has smooth borders and is not painful. In some instances, the texture of the spleen is irregular and knobby. In most older ferrets, an enlarged spleen is an incidental finding on physical examination.

Clinical Pathology and Diagnostic Testing

Results of the complete blood count (CBC) are usually unremarkable. Rarely adrenocortical disease is associated with nonregenerative anemia. If disease is severe or prolonged, pancytopenia may rarely be present. These changes mimic those in ferrets with estrogen-induced bone marrow toxicosis (see Chapter 4). In ferrets with anemia and pancytopenia, a packed cell volume less than 15% carries a grave prognosis.

Abdominal ultrasound is useful for detecting abnormal adrenal glands. The size, side of enlargement, and architecture can often be determined.11,53,54,71,74 In one study in normal ferrets, the mean dimensions (length and width) of the right adrenal gland were 7.6 + 1.8 by 2.6 + 0.4 mm, and those of the left adrenal gland were 7.2 + 1.8 by 2.8 + 0.5 mm.74 In another study, the mean dimensions of 28 abnormal left adrenal glands (length and thickness) were 9.2 ± 3.2 by 6.3 ± 3.0 mm, and dimensions of 19 abnormal right adrenal glands were 8.5 ± 2.5 by 5.2 ± 3.3 mm.53 In the same study, abnormal adrenal glands appeared on ultrasound as rounded with an enlarged cranial or caudal pole or both, a heterogeneous structure, and increased echogenicity; they were either with or without mineralization.53 Abdominal ultrasound is also useful for detecting concurrent diseases, such as renal or hepatic disease, metastasis from a pancreatic insulinoma, or enlarged lymph nodes. The presence of prostatic enlargement or uterine disease associated with adrenal gland disease can also be found by ultrasonography.11 Although not done routinely, advanced imaging studies such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a ferret’s abdomen can demonstrate adrenal gland abnormalities. In ferrets with right adrenal gland tumors, CT or MRI may be useful as a presurgical screening tool in determining involvement or invasion of the vena cava.9

Ancillary Diagnostic Tests

Several diagnostic tests used in dogs with adrenocortical disease are not useful in ferrets. The adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test and the dexamethasone suppression test cannot be used to diagnose adrenal disease in ferrets. Both normal ferrets and those with adrenal disease respond equally well to an ACTH stimulation test, probably because most ferrets with this disease do not produce abnormally high concentrations of cortisol.90 Plasma concentrations of ACTH and alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone in ferrets with adrenal disease are similar to those of normal ferrets, suggesting that adrenal disease in ferrets is independent of ACTH and alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone.96 Urinary cortisol/creatinine ratios were higher in 12 ferrets with adrenocortical tumors than in 51 clinically normal ferrets.39 In dogs, the urinary cortisol/creatinine ratio is a sensitive but not a specific indicator of hyperadrenocorticism. Further studies are needed to evaluate urinary cortisol/creatinine ratios in ferrets with diseases other than hyperadrenocorticism.

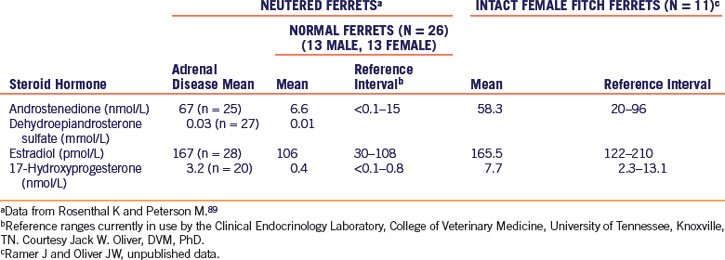

The measurement of serum or plasma concentrations of steroid hormones is a reliable means of diagnosing adrenal disease in ferrets. Hormone panels that measure estradiol, androstenedione, and 17-hydroxyprogesterone in blood samples are commercially available (Clinical Endocrinology Laboratory of the Department of Comparative Medicine at the University of Tennessee [http://www.vet.utk.edu/diagnostic/endocrinology/index]). In a normal neutered ferret, these steroids are found in minute quantities, whereas in ferrets with adrenal disease, the serum concentrations of one or more of these compounds may be high.89 In Table 7-1, reference intervals are given for androstenedione, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, estradiol, and 17-hydroxyprogesterone in intact female and neutered ferrets.

Differential Diagnosis

A ferret with an ovarian remnant or an intact female ferret may present with an enlarged vulva and alopecia, resembling a ferret with adrenal disease. However, ferrets with ovarian remnants are uncommon and tend to exhibit an enlarged vulva at an earlier age (first onset of estrus at one year of age) compared with the usual age of onset of adrenal disease (3-4 years of age). Several diagnostic methods can be used to differentiate the two conditions. In one method, human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) 100 IU IM is administered and then repeated in 7 to 10 days. If the ferret is intact or if an ovarian remnant is present, the vulva usually decreases in size. Alternatively, imaging methods such as abdominal ultrasound or measuring steroid hormone concentrations may help differentiate the two conditions. If the concentrations of androgens—such as androstenedione, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, or 17-hydroxyprogesterone—are high, an adrenal tumor is likely. If only the estradiol concentration is elevated, then either condition may be present. An ultrasound examination of the abdomen of a female ferret may differentiate between an adrenal tumor and an intact genital tract. Surgery is the definitive method to confirm the presence of ovarian tissue or an abnormal adrenal gland.

Possible Concurrent Abnormalities

Many ferrets with adrenal disease have splenic enlargement. Histopathologic examination of the spleen usually shows extramedullary hematopoiesis. Infrequently, neoplasia, including lymphoma and hemangiosarcoma, causes splenic enlargement. Nodular hyperplasia is also seen. In any ferret with an enlarged spleen that undergoes adrenalectomy, obtain a biopsy specimen of the spleen at the time of surgery (see Chapter 5).

Middle-aged and geriatric ferrets frequently have heart disease, which can be clinical or subclinical (see Chapter 5). Before surgery, all older ferrets should be evaluated for subclinical heart disease to prevent the decompensation that can accompany the effects of anesthesia or fluid administration.

There is one case report of concurrent primary hyperaldosteronism in a ferret with classic signs of adrenal gland disease. Persistent hypokalemia, high blood pressure measurements, and a high concentration of circulating aldosterone led to the tentative diagnosis of hyperaldosteronism, with a definitive diagnosis at necropsy.24

Management

The two treatment modalities for adrenocortical tumors are surgically removing all or part of an affected adrenal gland(s) or medical management. Surgical removal is the preferred treatment for most ferrets, as it is for dogs with adrenocortical tumors.52,101 With medical management, the growth of the adrenal tumor may not stop but clinical signs may regress either temporarily or permanently. However, medical management may be preferred for economic reasons or in ferrets that are geriatric or have concurrent disease.

Surgical Therapy

Adrenalectomy techniques are described in Chapter 11. At surgery, fully explore the abdomen before addressing the diseased adrenal gland(s). Other structures to be examined are the liver, the lymph nodes, the pancreas, the kidneys, and the spleen. Because bilateral adrenal gland disease can be present, both adrenal glands must be examined, palpated, and compared.

Perform a unilateral adrenalectomy if only one adrenal gland is diseased.101,110,112 If both glands are diseased, a subtotal adrenalectomy, with total removal of one gland and partial removal of the other, is indicated (see Chapter 11). Total bilateral adrenalectomy carries a high risk that drug therapy may be necessary for an unspecified time to replace corticosteroids and mineralocorticoids. In a retrospective study, slightly less than 10% of the ferrets undergoing surgery had bilateral adrenalectomy, but survival rates for that particular group were not reported.101

After surgery, administer maintenance and replacement fluids as needed. Unless concurrent gastrointestinal surgery was performed or complications develop, feed the ferret soon after surgery. Ferrets rarely need postoperative corticosteroid replacement therapy after simple unilateral adrenalectomy. If the ferret has a concurrent insulinoma or has had a subtotal adrenalectomy and appears very lethargic after surgery, giving prednisone at a starting dose of 0.1 mg/kg q12h for 2 to 3 days after surgery for glucocorticoid replacement may be considered. Monitor the blood glucose levels to determine the effectiveness of or need for medication. If a total or subtotal bilateral adrenalectomy has been performed, monitor electrolyte concentrations closely after surgery. Not all ferrets undergoing these procedures will need supplementation; therefore monitoring electrolyte levels, following trends in blood glucose levels, and performing serial physical examinations is required after surgery. If necessary, mineralocorticoid supplementation may be given as needed. Parenteral administration of mineralocorticoids has been reported with desoxycorticosterone pivalate (Percortin, Novartis, Greensboro, NC) at 2 mg/kg IM q21d, or oral supplementation can be used with fludrocortisone acetate (Florinef, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ) at a dosage of 0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg PO q24h or divided q12h.48

Medical Management

Ketoconazole

Because of its ability to inhibit the steroid biosynthetic pathway at several steps, ketoconazole is used in the treatment of adrenocortical disease in other species.95 However, it is not effective in ferrets.

Androgen Receptor Blockers

Androgen receptor blockers reverse the clinical signs of adrenal gland disease but do not inhibit the growth of an abnormal adrenal gland. Theoretically these compounds act at the receptor site to block the actions of androgens. In human medicine, these drugs are used to treat men with benign prostatic hyperplasia or prostatic carcinoma.1,7,22,64 Like all medical therapies used in ferrets with adrenal disease, androgen receptor blockers are effective in some but not all ferrets. Flutamide (Eulexin, Schering Corporation, Kenilworth, NJ) and bicalutamide (Casodex, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Wilmington, DE) have been used in ferrets with adrenal disease.48 Flutamide has been used in ferrets for behavioral research.108

Aromatase Inhibitors

Another class of drugs that can depress the signs of adrenal disease in ferrets comprises the aromatase inhibitors. One drug that has been used is anastrozole (Arimidex, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Wilmington, DE). This drug specifically inhibits aromatase, the enzyme that catalyzes the final step in estrogen production. In people treated with continued dosing of anastrozole, plasma concentrations of estradiol decrease approximately 80% from baseline.38,80 Anastrozole has little or no effect on central nervous system, autonomic, or neuromuscular function.

Melatonin

In the mink industry, melatonin implants are used to force early molt to produce optimal winter pelt development for the fur industry; they have also been used in studies of seasonal pelage cycles.49,85 In one study, oral administration of melatonin in ferrets did not stop the progression of adrenal gland disease and/or inhibit the continued growth of the affected adrenal glands. However, melatonin treatment improved hair growth and resulted in reduced prostatic or vulvar size in ferrets with adrenal gland disease for at least 8 months.85 Oral administration of melatonin may not be practical in pet ferrets, but a long term implantable form of melatonin (Ferretonin, Melatek, Middleton, WI) is available. According to the manufacturer, Ferretonin at either a 5.4 mg or 2.7 mg depot of melatonin gives four months of relief to signs of adrenal gland disease in ferrets.

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Analogs

GnRH analogs are a class of compounds that are widely used in human medicine to treat prostatic cancer, endometriosis, and breast cancer.49 In ferrets, these compounds have been used to control the signs of adrenal gland disease. There are two general types of analogs: GnRH agonists and GnRH antagonists.

During short-term or intermittent therapy, GnRH agonists have the same stimulatory action as GnRH, but long-term therapy suppresses the production and/or release of LH and FSH by downregulating the receptors at the pituitary.105 This downregulation of receptors is the mode of action of the agonists. Two currently used injectable GnRH agonists used in ferrets with adrenal gland disease are leuprolide acetate (Lupron Depot, TAP Pharmaceuticals Inc., Lake Forest, IL) and deslorelin acetate (Suprelorin, Peptech Animal Health Pty Limited [Virbac], NSW, Australia).49,105

Leuprolide acetate (Lupron) was the first GnRH agonist to be widely used in the treatment of ferret adrenal gland disease.49,106 Currently, two types of depot formulations of this agent are commercially available: a 1- or 4-month formulation.48,49 The 1-month formulation appears to be more consistently effective.48 The reported dose range is 100 to 250 mcg/kg or 100 to 200 mcg per ferret IM. The response to this injection may last from 1 to 4 months.48,106

Deslorelin is similar in action to leuprolide but appears to provide a longer disease-free interval than leuprolide.105,107 In one report, the response to a single 4.7-mg implant of deslorelin acetate lasted between 8 and 30 months.105 It is likely that once deslorelin is approved for use and distribution in the United States, it will become the drug of choice for treating ferret adrenal gland disease.

In humans, GnRH antagonists are being studied for treatment of many of the same diseases in which agonists are currently used. Theoretically antagonists should be more effective than agonists but at a much lower dose. In human medicine, an antagonist called abarelix is being evaluated to determine its ability to inhibit the action of GnRH. This or similar drugs may eventually replace GnRH agonists in the treatment of ferret adrenal disease.

Adrenal Histopathology

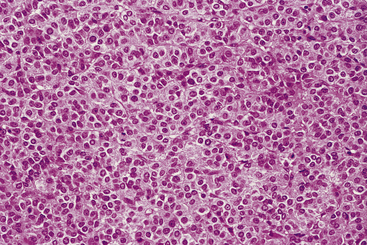

On histopathologic examination, adrenal gland disease is described as adrenocortical hyperplasia, adenoma, or carcinoma.91 One study describes spindle cell-variant adrenal tumors in adrenal gland disease.73 The spindle cell component of these variant adrenal tumors is smooth muscle in origin and may be associated with a more malignant grade of this tumor.73 Another study describes a variant of adrenocortical carcinoma with prominent mucin production, interpreted as myxoid differentiation. In ferrets, adrenocortical carcinoma with myxoid differentiation appears to be more malignant than carcinoma, its well-differentiated counterpart.79 Although adenomas appear to be most common, the clinical behavior of these tumors and hyperplasia is usually identical. Metastasis is uncommon; however, some tumors locally invade the vena cava or liver. Very rarely, carcinomas can metastasize to the lungs. Pheochromocytomas occur uncommonly in ferrets (see below).

Prognosis

The prognosis with surgical treatment is good in the hands of an experienced and skilled surgeon. In one study of 130 ferrets that were treated with surgery for adrenal gland disease, the 1- and 2-year survival rates were 98% and 88% respectively.101 In most ferrets, the associated clinical signs resolve after the diseased adrenal gland has been removed. Owners should be instructed to watch for recurrence of adrenal gland disease, especially if not all of the adrenal gland tissue is removed. Clinical signs of recurrence are alopecia, vulvar enlargement, and pruritus. Later complications of surgical treatment include recurrence of adrenal tumor because of metastasis (rare) or the development of an adrenocortical tumor in the remaining adrenal gland.101 In one study, recurrence of signs after bilateral adrenalectomy developed in 15% of cases, with a mean long-term follow-up period of 30 months.110

Pheochromocytomas

Pheochromocytomas occur rarely in ferrets.34,101 Pheochromocytomas arise from the adrenal medulla and produce excessive amounts of catecholamines (Fig. 7-4). Clinical signs are primarily associated with the effects of catecholamines on the cardiovascular system. In clinical cases seen at the Animal Medical Center in New York City, several ferrets exhibited clinical signs consistent with those seen in dogs with pheochromocytomas: tachycardia, dyspnea, and cardiovascular collapse (K. Quesenberry, personal communication, 2002). High blood pressure is a common finding in other species; however, blood pressure was not measured in these ferrets. Because clinical signs of pheochromocytomas are not obvious, retrospective studies are used to determine the incidence of pheochromocytomas in relation to adrenocortical disease. In one study, 5 pheochromocytomas were associated with 131 adrenal gland masses (3.8%).101 In another study, the percentage of pheochromocytomas in adrenal tumors was similar (3%).78 However, the incidence of pheochromocytomas in ferrets without clinical signs attributed to adrenocortical disease is unclear. Histologic diagnosis of a pheochromocytoma is confirmed by immunohistochemical staining. Animals with pheochromocytomas respond poorly to chemotherapy, and surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Prognosis in ferrets with pheochromocytomas is poor.

Thyroid Disease

Clinical hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism have not been reported in ferrets. In one report of medullary thyroid carcinoma diagnosed at necropsy, functional hyperthyroidism was not confirmed antemortem.34 Resting values for thyroxin and tri-iodothyronine and results of thyroid-stimulating hormone testing reported in one study of normal intact male ferrets are presented in Table 7-2.43

Table 7-2 Reference Values for Endocrine Tests in Ferrets

| Hormone | Sex | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Cortisol (nmol/L)a | 25.9-235 (mean, 73.8) | |

| Thyroxine (μg/dL)b | M | 1.01-8.29 (mean, 3.24) |

| F | 0.71-3.43 (mean, 1.87) | |

| Tri-iodothyronine (ng/mL)b | M | 0.45-0.78 (mean, 0.58) |

| F | 0.29-0.73 (mean, 0.53) | |

| Mean thyroxine (μg/dL)c | M |

a Administration of cosyntropin, 1 μg/kg IM, generally caused a three- to fourfold increase in plasma cortisol concentration. Data from Rosenthal KL, Peterson ME, Quesenberry KE, et al.90

b Data from Garibaldi BA, Pequet Goad ME, and Fox JG.37

c Mean thyroxine at baseline (0 hours) and 2, 4, and 6 hours after intravenous administration of 1 IU of thyroid-stimulating hormone (n = 8 intact males). Data from Heard DJ, Collins B, Chen DL, et al.43

Suspected pseudohypoparathyroidism was reported in a 1.5-year-old neutered male ferret.114 Pseudohypoparathyroidism, a hereditary condition in humans, results from a lack of response to circulating parathyroid hormone rather than hormone deficiency. The ferret was seen because of intermittent seizures, and results of diagnostic tests revealed low serum calcium, high serum phosphorus, and high serum parathyroid hormone concentrations. The ferret responded to long-term treatment with dihydrotachysterol, a vitamin D analog, and calcium carbonate.

Diabetes Mellitus

History and Physical Examination

Spontaneous diabetes mellitus is very uncommon in ferrets.10,14 Most ferrets develop iatrogenic diabetes from aggressive pancreatectomy to debulk beta-cell tumor nodules. The clinical signs of diabetic ferrets are similar to those of other species. The severity of such signs depends on the severity and chronicity of the disease. Affected ferrets are polyuric and polydipsic and may lose weight despite a good appetite. They often appear lethargic, especially if a metabolic derangement such as ketoacidosis is present.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree