Malgorzata Pozor

Emergencies in Stallions

Emergencies in breeding stallions can pose a substantial threat to their future reproductive careers, and prompt diagnosis and appropriate intervention in emergent situations are essential in preserving reproductive function.

Scrotal Emergencies

In a breeding stallion, any acute onset of painful swelling in the scrotum or its contents is an emergency. Affected stallions may develop signs of mild to severe colic that can mimic gastrointestinal problems. If the condition is untreated, the pain can persist for a prolonged period of time, although after the affected testis becomes nonviable, pain may decrease in severity or subside completely. The acutely painful scrotum poses a diagnostic challenge because it can be a result of spermatic cord torsion, inguinal hernia, trauma, epididymitis, orchitis, or neoplasia.

Torsion of the Spermatic Cord

Torsion of the spermatic cord is relatively rare, but horses with a long gubernaculum (the proper ligament of the testis or ligament of the tail of the epididymis) or a long mesorchium are especially prone to developing this condition. Very occasionally, cryptorchid testes rotate in their intraabdominal location, leading to torsion of the spermatic cord and signs of colic for which it can be difficult to determine the cause. Torsion of the spermatic cord less than 180 degrees causes increased resistance to blood flow in the affected testis but does not cause clinical signs and does not appear to have a significant effect on fertility. In one report involving a 270-degree torsion of 24 hours’ duration in a stallion, the torsion led to scrotal and preputial swelling, fever, and engorged testicular vessels, but the testis remained viable and was successfully salvaged by surgical fixation of the testis in its normal position.

Torsions of 360 degrees or greater result in vascular compromise and ischemia of the testis, causing severe scrotal pain and swelling. Edema can extend into the ipsilateral hind limb, and the horse’s gait can be affected. Pain is often acute and severe, but it can also be intermittent or mild to moderate. In chronic cases, pain can decrease in severity or completely disappear, which is consistent with loss of viability in the affected testis. The scrotum should be manually palpated to determine the tail of the epididymis and assess the degree of torsion. However, the affected testis is often retracted and pulled close to the external inguinal ring, where it is difficult to palpate.

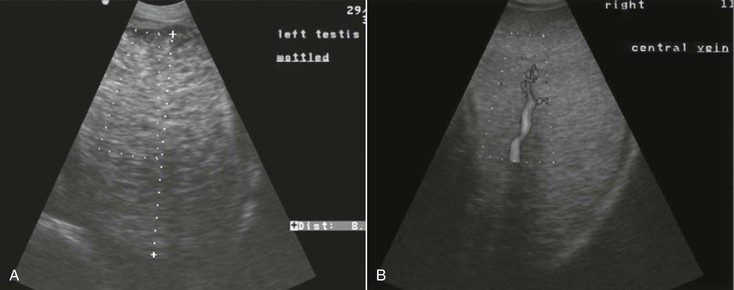

Initially, B-mode ultrasound imaging of the affected testis is unremarkable, but soon after the onset of torsion, venous congestion and edema develop, causing decreased echogenicity of the testicular parenchyma. When hemorrhage and necrosis develop, heterogenous echogenicity results, which suggests that the affected testis cannot be salvaged (Figure 151-1). The spermatic cord is congested and enlarged above the twisted region and may have signs of thrombosis. The torsion site, which is narrower and hyperechoic, can be identified by the whirlpool appearance. The epididymis should be identified and traced to the epididymal tail by use of B-mode ultrasonography.

To further localize the site of torsion, multiple cross-sections of the spermatic cord can be imaged with color Doppler ultrasonography, with the unaffected testis used for comparison (see Figure 151-1). Multiple cross-sections of the cord are imaged to detect the site of torsion. Blood flow will be seen proximal to the site but will be diminished or completely absent below it. If no Doppler signal is detected in the affected testis with the standard parameters used for identifying peripheral blood flow, the ultrasound parameters should be modified (to settings of high gain, low pulse repetition frequency, and low wall filter) to identify very low flow. Power Doppler can also be used to detect a very weak flow signal. Use of pulsed-wave spectral analysis of blood flow in the marginal part of the testicular artery on the unaffected side enables determination of whether the torsion has resulted in reflex vasospasm in the contralateral testis, increased vascular resistance, or reversed diastolic flow in the affected testis.

Treatment of clinically significant torsion of the spermatic cord in stallions is surgical: the testis on the affected side is removed to prevent negative effects on the healthy contralateral testis. Experimental torsion of the spermatic cord in rodents triggers sympathetically mediated reflex vasospasm, leading to hypoxia of the contralateral testis. Furthermore, if the affected testis undergoes necrosis, an autoimmune response ensues and antisperm antibodies are produced, causing cellular injury in the contralateral testis. In rodents, medical treatment with immunosuppressants, vasoactive medications, and antioxidants successfully modulates these effects. The efficacies of these treatments in stallions with torsion of the spermatic cord have not been tested.

Inguinal Hernia

Inguinal hernia is a broad term that refers to invagination of a loop of intestine into the inguinal canal only (inguinal hernia) or extended into the scrotum (scrotal hernia). Inguinal hernias, which are usually unilateral, may be indirect or direct, congenital, or acquired. Indirect hernia occurs when abdominal viscera that have entered the inguinal canal are located inside the vaginal process. Direct hernia exists when the abdominal viscera entering the inguinal canal are located outside the vaginal process. Congenital inguinal hernias occur in foals and are associated with the relatively large inguinal rings. Strong compression of the fetus’ abdomen during parturition may also contribute to herniation of intestine. In contrast to acquired indirect hernias in adult horses, congenital hernias in foals are usually painless.

Acquired indirect hernias are seen in stallions of various ages and breeds. Reports in the literature contain conflicting information regarding the association of indirect hernias with certain breeds (Standardbreds and Andalusians), certain activities (mating, strenuous exercise, or abdominal trauma), and large inguinal rings, and some report a higher incidence on the left than on the right side. The jejunum and ileum are involved in most inguinal hernias in horses, but involvement of the large colon has been reported in a few cases.

Stallions with acquired inguinal hernia typically develop signs of colic that vary in severity. If the intestines are not incarcerated, the only presenting sign may be an enlarged scrotum. However, in most instances, the veterinarian is called to examine the horse only after the horse is painful and has tachycardia, tachypnea, a high packed cell volume, and prolonged capillary refill time. Signs of toxemia appear if the involved intestine becomes devitalized. On palpation, the affected side of the scrotum can be tender or very painful, and occasionally one or more loops of intestines are palpable. Ultrasonography is the method of choice for confirming the presence of intestine in the vaginal cavity when characteristic peristaltic movements are visible. Perfusion of the intestinal segment, testis, and scrotal wall should be evaluated with color Doppler ultrasonography. Rectal palpation should always be performed to detect structures that have entered the external inguinal ring. The involved portion of intestine may be clearly invaginated into the inguinal canal or only located close to the internal inguinal ring. Because the lumen and venous drainage are obstructed in herniated bowel segments, edematous or distended loops of intestine may be detected in the caudal part of the peritoneal cavity.

Most congenital inguinal hernias in colts are manually reduced and managed with a truss or other suspensory device. They usually resolve spontaneously after approximately 3 months. Only direct hernias and indirect hernias resistant to manual reduction require surgical intervention. Although minimally invasive laparoscopic techniques can be used to retract herniated intestine into the abdominal cavity, open surgery is the most common method used to repair an acquired inguinal hernia in an adult stallion. An incision is made at the external inguinal ring or over the testis to reduce the hernia, and another incision is made on ventral midline to inspect the intestines, resect nonviable segments, and reduce the size of the internal inguinal rings. Castration is often performed simultaneously, but owners often insist on saving the testes, if possible. These owners should be informed about a possible hereditary component to the pathogenesis of inguinal hernia in horses.

Recently, a novel technique was described for manual reduction of incarcerated inguinal hernias in adult stallions under general anesthesia. The horse is positioned in dorsal recumbency, with the hind limbs hoisted in a semi-flexed position. The operator holds the testis down in the scrotum while the scrotal neck is massaged until the invaginated loop of intestine is replaced back into the abdominal cavity. In a series of 40 cases, 33 (82.5%) were successfully reduced with this technique, but stallions with a strangulated hernia of more than 5 hours’ duration also underwent exploratory laparotomy so that viability of the strangulated intestine could be assessed.

Scrotal Trauma

Scrotal trauma is usually associated with a breeding or teasing accident, with jumping through a high fence, or, rarely, with human abuse. Severe trauma may cause scrotal lacerations, hematoma, orchitis, periorchitis, rupture of the tunica albuginea or testis, abscess, and other lesions. The prognosis for preserving the testis is guarded, depending on the extent of injury.

Even mild scrotal trauma may cause substantial soft tissue swelling and signs of discomfort. Rupture of one or more branches of testicular vessels leads to extravasation of blood into the vaginal cavity and formation of a hematocele. Occasionally, traumatic hydrocele can develop. More serious injuries include damage to the testis and epididymis, resulting in testicular hematoma, segmental infarction, and focal necrosis. As a result of massive swelling of testicular parenchyma within the confined space of the tunica albuginea, compartment syndrome can develop and cause additional vascular compromise. In the most severe cases, the tunica albuginea ruptures and testicular tissue herniates. Scrotal trauma is sometimes associated with a penetrating testicular injury that inoculates bacteria and leads to orchitis, pyocele, abscess formation, and epididymitis.

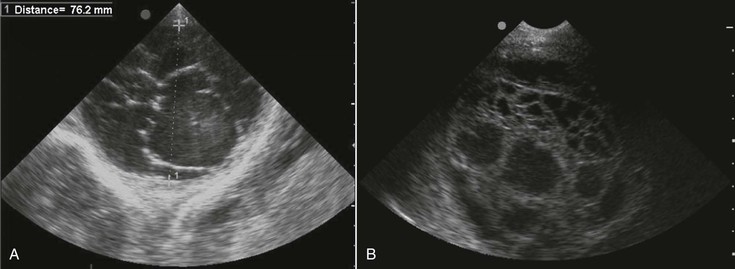

The first signs of scrotal trauma are swelling, pain, and unilateral lameness. Subsequently, the swelling may expand into the prepuce, the scrotum becomes firm and warm, and signs of systemic involvement may appear. Regardless of the severity of these clinical signs, each case of scrotal trauma should be treated as an emergency. Hematocele, hydrocele, or pyocele is indicated by a palpable collection of fluid in the vaginal cavity, the character of which can be determined with ultrasound. Nonechoic, clear fluid is consistent with either hydrocele or recent hematocele. Cellular content or swirling is often visible in a longer standing hematocele. After 1 or 2 days, extravasated blood organizes, and hyperechoic fibrin strands become visible (Figure 151-2). Although hydrocele and hematocele can be seen immediately after a traumatic incident, pyocele and abscesses take time to develop. The sonographic appearance of scrotal abscesses varies considerably and probably depends on the causative organism. They may be uniformly echogenic, cystic, and hypoechoic or anechoic, or multicystic with heterogenous echogenicity. This can be confusing and may lead to misdiagnosis. A rapidly increasing local and systemic body temperature is more consistent with a developing abscess than with a hematocele or hydrocele.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree