Chapter 9 Eliminative behavior

Development of eliminative responses

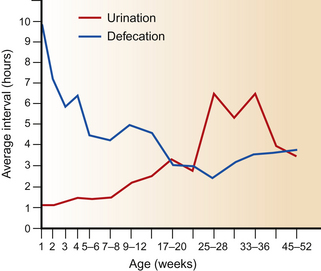

As a reflection of the changing nature of water balance from neonate to juvenile and the concurrent shift in diet, the frequency of urination decreases as that of defecation increases with maturity (Fig. 9.1). By 5 months of age, defecation has plateaued from approximately twice per day in the first week of life so that it occurs every 3–4 hours.1 Urination, on the other hand, declines from an hourly event to one that occurs about six times per day.1 Perhaps because they can tolerate greater distensions of their bladders, filly foals are generally twice as old as colts when they first urinate (10.77 hours post-partum versus 5.97).2

Defecation

Horses can be prompted to defecate by the sight of feces or the action of another horse defecating. Drinking is also thought to provide a stimulation to dung,3 possibly via a gastro-colic reflex.4 Arousal in the form of both fear and excitement can also stimulate horses to defecate,5 sometimes to the extent of intestinal hurry, as manifested by the presence of undigested grain. It is currently unclear whether feces and urine from fearful horses provide olfactory warning cues to conspecifics, as has been shown in cattle and pigs.6,7

Horses tend to show considerable care in selecting defecation sites since they return repeatedly to areas that are not used for grazing. Fecal material makes the grass in latrine areas less appealing, even though the grass itself is readily consumed if presented to horses without the fecal material.8 This response, which develops in foals as they mature and become less attached to their dams,9 prompts the development of so-called latrine and lawn areas.1 The tendency to defecate in soiled areas means the main body of pasture carries fewer parasites. This strategy is appropriate for free-ranging horses that have a virtually unlimited range but in smaller fenced grazing areas it behoves management to institute rotational grazing to break the lifecycle of endoparasites.

The vestiges of dunging strategy are sometimes evident in stabled horses that show an attempt to select sites. As noted by Mills et al,10 when given the choice between two bedding substrates in looseboxes joined by a passageway, horses defecated in the passageway more than in either box. This could reflect the association between movement (between boxes when exercising choice) and hindgut motility, but should prompt further investigation into the aversiveness felt by horses to fecal material and the extent to which welfare may be compromised by making horses stand in close proximity to their own excrement for extended periods, as is the case in standard husbandry. Certainly, pastured horses tend to move forward after defecation.9 Porcine studies have provided a possible model by demonstrating the olfactory threshold of the pigs for concentrations of ammonia in the air.11 Since urine and fecal material may be offensive, not least because of their ammonia content but also because they attract flies, compounds such as sodium bisulfate that have been shown to decrease ammonia concentrations and behavior typical of horses being bothered by flies should be integrated in the stable hygiene routine.12

Some owners who note that their horses (often geldings rather than mares) repeatedly defecate in feed buckets, sometimes interpret this behavior as a form of protest. A more likely explanation is the establishment of a habitual dunging pattern that coincides with relatively little space and therefore few alternatives other than that in which the receptacle is routinely placed. Hanging the haynet over the favored site (and ensuring that plenty of hay is contained within it) is usually effective in keeping the horse oriented appropriately and capitalizing on the innate equine tendency to move away from a foraging site prior to defecation. Despite such efforts, some horses do seem to target their food and water receptacles and repeatedly compromise their own ingestive activities as a result. Intriguingly, it appears that Thoroughbreds are more likely to perform this behavior than other breeds.13 Ethologists note that the response is seen mainly in buckets that are placed on the wall next to the stable door and suggest that barrier frustration may contribute to the etiology.13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree