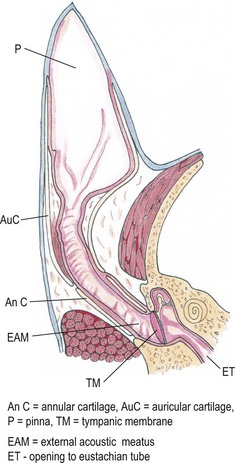

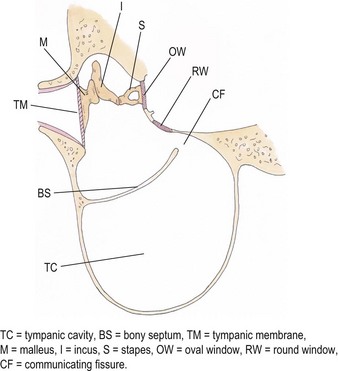

Chapter 50 The ear is a sensory organ that receives and transforms the vibrations perceived as sound into neural impulses conveyed to the brain. The ear is composed of the pinna, external ear canal (comprising vertical and horizontal ear canals), the middle ear, and the inner ear (Fig. 50-1). Figure 50-1 Diagram illustrating the anatomy of the feline ear. (Reprinted from Slatter DH (2003) Textbook of Small Animal Surgery 3e, with permission from Elsevier.) The middle ear cavity contains three parts: the dorsal epitympanic recess (or attic), the tympanic cavity proper, and the tympanic bulla (Fig. 50-2). Figure 50-2 Diagram illustrating the feline tympanic bulla. (Reprinted from Slatter DH (2003) Textbook of Small Animal Surgery 3e, with permission from Elsevier.) Clinical signs of vestibular disease include a head tilt towards the affected side or wide excursions of the head if the disease is bilateral, asymmetric ataxia, typically with leaning, stumbling, falling or rolling to the affected side, or symmetric ataxia if both sides are equally affected, and spontaneous horizontal or rotatory nystagmus, with the fast phase away from the affected side. Nausea and vomiting may be seen due to vestibular input to the vomiting center in the brainstem. Peripheral vestibular disease should be differentiated from central vestibular disease (Table 50-1). Rarely, extension of inner ear disease into the CNS may cause brainstem dysfunction. Neurologic signs indicating middle ear involvement may be seen in 25% of cats with external ear canal tumors. Table 50-1 Neurologic findings in vestibular system dysfunction Examination of the patient, using various means, is indicated to answer the questions listed in Box 50-1. Both ears should be examined, even in animals with unilateral signs, as bilateral disease of different severities may be present. The less affected ear should be examined first and a new otoscope cone should be used for each ear. If a large amount of discharge is present, the ears may need to be flushed before examination can be conducted. In animals with marked erythema, proliferation, stenosis or ulceration, administration of topical or systemic corticosteroids for seven–14 days may be needed to decrease the inflammation and pain and open up the external ear canals so that a full examination may be performed. The use of a video-otoscope (Fig. 50-3A), rather than a hand-held otoscope (Fig. 50-3B) has a number of advantages to consider (Box 50-2). Figure 50-3 Equipment used for evaluation of the external ear canal and tympanic membrane. (A) Video-otoscope. (B) Handheld otoscope. Samples should be taken from both ears and should be taken before use of any cleaning agent or therapy. A cytology sample may be obtained by using a cotton-tipped applicator inserted gently into the external ear canal. Samples obtained from the deeper horizontal canal are more clinically relevant than samples obtained from the vertical canal, although this is best performed with the animal under anesthesia. In cats with otitis media, samples obtained from the tympanic cavity are more representative. The swab is then rolled onto a clean glass microscope slide, evenly distributing a thin layer of material. Cerumen has a high lipid content and briefly heating the slide will fix the material to the slide and avoid loss of the sample in the stain solvent. A simple, rapid in-house stain using a modified Wright’s stain (e.g. DiffQuick) is adequate. A Gram stain is more time consuming and may not be necessary as most cocci found in the ear are Gram positive and most rods are Gram negative. If parasites are suspected, mounting the otic exudate in a few drops of mineral oil on a slide followed by a coverslip is suitable and this should be performed in all cats with otitis externa. Examination for Demodex should similarly be performed in adult cats with pruritic otitis externa as this condition is uncommon but certainly underdiagnosed.1 The normal cerumen is waxy and yellow and, due to the high lipid content, does not take up stain and therefore a cytology slide from a normal ear should be almost colorless. Normal cornified squamous epithelial cells and desquamated keratinocytes may be seen. Small numbers of resident bacteria may be identified in 71% of cats,2 usually Gram positive cocci: coagulase negative Staphylococcus spp., coagulase positive Staphylococcus spp., and Streptococcus spp. Rods are rarely found in the normal ear canal, with the exception of Corynebacterium.2,3 Bacteria found in the presence of leukocytes should be considered an abnormal finding. Malassezia is a normal resident of the feline ear canal, being found in 23% to 83% of normal cats,2,4 but it is also an opportunistic pathogen and is found in 64% of cats with otitis externa.5 Abnormal findings include increased numbers of Malassezia organisms (greater than 12 organisms per high dry [×40 objective] field).6 Less than two organisms is considered normal and two to 11 is considered a gray zone. This cut off has a specificity of 100% and sensitivity of 63% for Malassezia infection in cats. Bacteria identified on cytology may be normal flora, bacterial overgrowth in the debris and on the epithelial surface, or true infection. Semiquantitative cytologic criteria may help to identify the clinical importance of bacteria. Four or fewer bacteria per high dry field may be considered normal, five to 14 is of unknown importance, and 15 or more is abnormal.6 This cut off has 100% specificity and 63% sensitivity in cats. The presence of a large number of leukocytes, which are not usually found in normal cerumen, particularly if they contain phagocytosed bacteria, also provides evidence in support of true infection, although leukocytes may be seen in other forms of ear disease, e.g., immune-mediated dermatopathies. Cytology may also be used in the evaluation of masses involving the external ear canal.7 In one study of 27 masses from 25 cats, fine needle aspirate cytology showed a good level of agreement with the final histologic diagnosis and was able to differentiate all inflammatory polyps from other tumors. However, cytology was less useful in differentiating between benign and malignant neoplasia, being correct in 22 out of 27 masses (81.5%).7 In cats with otitis media, the most common bacterial pathogen is Staphylococcus intermedius, although other organisms including streptococci spp, Pseudomonas, Proteus, Bordetella, Bacteroides, Fusobacterium, and Mycoplasma have been reported.8 Bacterial resistance is not usually a problem in feline otitis media compared with the situation in dogs. Bacteria of the same species isolated from the middle ear and the horizontal ear canal may display different antibiotic sensitivity patterns in up to 80% of cases.9 The selection of the most appropriate diagnostic imaging technique depends on the particular question being asked and the differential diagnoses being considered.10 For instance, in an animal with otitis externa with suspected otitis media, radiography or CT is appropriate, with CT having a role to play even if radiographs do not reveal any abnormality. In a cat with a suspected nasopharyngeal polyp, a CT has greater sensitivity for detection of a mass in the middle ear and nasopharynx, although these areas can still be imaged with radiographs. An MRI scan has the greatest sensitivity, particularly for acute otitis media, but assessment of the bony structures of the middle ear is difficult with MRI. In a cat with signs of vestibular disease, an MRI provides the most useful information for evaluation of inner ear structures, but a CT may be useful to assess the middle ear if otitis interna arose from otitis media. Projections include lateral, dorsoventral or ventrodorsal, latero 20° ventral-laterodorsal oblique, rostro 10° ventral-caudodorsal closed-mouth oblique11 and rostro 30° ventral–caudodorsal open-mouth oblique.12 The ventrodorsal view is better for evaluating a patient with otitis externa, although positioning is easier for the dorsoventral view. Of the two rostroventral-caudodorsal oblique projections, the 10° closed-mouth oblique is more accurate and easier to perform, although there is no difference in the accuracy of these views for the detection of fluid in the middle ear.13 Contrast radiography may be of use on occasion. Positive contrast canalography, after instillation of a water contrast iodinated solution into the external ear canal, may be used to assess the integrity of the tympanic membrane and to assess the integrity of the external ear canal, e.g., in patients with suspected ear canal avulsion or stenosis, and the success of any repair.14–16 Water soluble iodine-containing contrast medium (1–2 mL) is instilled into the ear canal with the patient either in lateral recumbency, or, preferably in ventral recumbency so that a dorsoventral projection may be used to compare both external ear canals at the same time. In normal canine ears, positive contrast canalography was more sensitive than otoscopy in identifying iatrogenic tympanic membrane perforation.16 Positive contrast sinography may also be used in patients with chronic draining tracts after total ear canal ablation or accidental trauma to the ear canal (See Fig. 50-9B). Inner ear disease rarely produces signs visible radiographically. Ultrasonography is not commonly used, but has several potential advantages, as it is relatively quick, non-invasive and may be used in conscious patients.17 In a normal animal, air in the external ear canal and middle ear prevents transmission of ultrasound waves, but if the external ear canal is filled with fluid, e.g., saline, or if the middle ear contains soft tissue or fluid as a result of disease, then these structures may be examined. In one study ultrasonography was more accurate than radiography in the detection of fluid in the middle ear in feline cadavers, although both modalities were inferior to CT.18 Caution should be exercised when evaluating the thickness of the tympanic bulla wall in animals with fluid in the middle ear, as the thickness of the wall of a fluid-filled bulla appears greater than that of an air-filled bulla, due to a volume averaging artifact.19 CT has been found to be a more sensitive but less specific modality for the diagnosis of middle ear disease, although neither modality was able to detect early lesions associated with otitis media/interna when there was no osseous involvement.20 Another study showed that CT and radiographs have a similar sensitivity for detection of otitis media.21 Sensitivity is increased if a smaller slice thickness is chosen.10 Otitis interna is difficult to diagnose with CT except where there is marked destruction of the inner ear. MRI produces images with better soft tissue contrast than radiography or CT and is indicated if peripheral or CNS disorders are suspected, such as tumors, inflammatory lesions, or abscesses associated with ear disease.22 However, osseous lesions of the middle ear are difficult to assess with MRI and MRI requires general anesthesia. MRI is superior to radiography in the detection of middle ear disease in cats.23 MRI findings of otitis interna are lack of signal intensity of the labyrinthine fluid on T2W sequences24 and meningeal enhancement on post-contrast T1W sequences.25 Samples of fluid from the middle ear are required to make a diagnosis of otitis media. A myringotomy may be needed if the material in the middle ear is too thick to aspirate (see Box 50-7). This is used to assess the integrity and function of the peripheral and central auditory pathways and for indirect assessment of the closely associated vestibular pathways. This test is a recording of sound-evoked electrical activity in the auditory pathway between the cochlea and the auditory cortex. Sedation or anesthesia is required for this test to be conducted. Small (27G) needle electrodes are placed subcutaneously in the skin of the head and connected to an amplifier. The brain activity is measured after delivery of clicks at 10–20Hz through earphones in the external ear canal.26–28 Wounds that involve both skin surfaces and the cartilage will have a better cosmetic outcome if sutured, although these wounds may be left to heal by second intention (Fig. 50-4). Lacerations on the ear margin may widen with time as a result of contracture if allowed to heal by second intention, but if closed, wounds in this location may result in ‘cupping’ or folding of the ear margin as a result of contraction. Small wounds on the margin of the pinna may be treated with partial amputation of the pinna (subtotal pinnectomy) to avoid these cosmetic changes. Aural hematoma (Fig. 50-5) is a common disorder of the pinna, resulting either from trauma, which may be self-trauma due to head shaking or scratching, or external trauma, e.g., from a cat-fight wound, or from immune-mediated disease.29 In cats, otitis externa associated with ear mites is often noted and is usually unilateral. Hemorrhage results in sanguinous fluid accumulating between the cartilage and skin on the concave inner surface of the pinna, although analysis of this fluid suggests an exudate rather than frank blood.29 Further head shaking or self-trauma results in continuing bleeding and formation of a hematoma. Left untreated, the hematoma matures, leaving a sanguinous seroma, and then granulation tissue forms on the wall of the cavity. Contraction and fibrosis then result in pinnal deformity (‘cauliflower ear’) and thickening. Figure 50-5 Aural hematoma on the concave (inner) aspect of the pinna results in convex appearance due to accumulation of sanguinous fluid. Drainage of the hematoma may be achieved in several ways. Needle aspiration of the hematoma is the simplest method, but may not be effective if the hematoma is chronic and may need to be repeated if the hematoma recurs before the cavity has been obliterated. Corticosteroids may be used to reduce local inflammation, reduce head shaking and self-trauma, and suppress an autoimmune reaction if one is present.29,30 Although these are probably best given systemically, as administration into the hematoma cavity has the potential to maintain the separation between the cartilage and skin and prolong healing. There are a variety of surgical options reported for aural hematoma management31–36 (see Box 50-13). Tumors arising from the ear are uncommon in cats, and usually affect the pinna and external ear canal. Benign tumors are less common than malignant tumors, although the most frequent proliferative lesion is the inflammatory polyp. Benign tumors are less likely to be ulcerated, tend to have a narrow base of attachment, are more likely to be lobulated and typically do not invade the ear cartilage.37 SCC is the most common tumor of the feline pinna (Fig. 50-6). SCC usually affects light-colored cats exposed to UVB.38 These tumors are often actinically induced as a result of DNA damage following exposure to solar radiation. Tumors are more frequent in regions with the highest solar radiation. In such regions, the incidence of cutaneous SCC has been reported to be 27 cases per 100 000 cats.39 Thin-haired and light-colored cats are at risk, with white cats being 13 times more likely to develop this tumor.39 Lesions are most common where the hair is thin and exposure to the sun is greatest, i.e., pinna, especially the concave aspect and base, eyelids and nasal planum. SCCs are discussed further in Chapter 20.

Ear

Surgical anatomy

Middle ear

General considerations

Clinical signs

Clinical signs

Peripheral vestibular disease

Central vestibular disease

Head tilt

Towards the lesion

Towards the lesion (or away from the lesion with paradoxical disease)

Spontaneous nystagmus

Horizontal or rotatory with the fast phase away from the side of the lesion, rarely positional

Horizontal, rotatory, vertical and/or positional, with the fast phase toward or away from the lesion; the direction may change with head position

Paresis/proprioceptive deficits

None

Common ipsilateral to the lesion

Mentation

Normal to disorientated

Depressed, stuporous, obtunded or comatose

Cranial nerve deficits

Ipsilateral CN VII deficit

Unilateral or bilateral CN V, VII, IX, X and XII deficits

Horner syndrome

Common ipsilateral

Uncommon

Head tremors

None

Seen with concurrent cerebellar dysfunction

Circling

Infrequent, may occur toward side of lesion

Usually toward the side of the lesion

Diagnostic procedures

Otoscopy

Clinical pathology

Cytology

Culture

Diagnostic imaging

Radiography

Ultrasound

Computed tomography

Magnetic resonance imaging

Sampling the middle ear and myringotomy

Additional tests

Brainstem-evoked auditory responses (BEAR)

Surgical diseases of the pinna

Trauma

Aural hematoma

Pinnal neoplasia

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Ear