CHAPTER 59Dystocia and Fetotomy

TERMINOLOGY

In any discussion of obstetrics it is essential that there be a uniform appreciation of the terminology. Dystocia is defined as being abnormal or difficult labor—be it maternal (e.g., uterine torsion, pelvic anomaly, abdominal hernia) or fetal (size, presentation, position, posture) in origin.1,2 While premature separation of the placenta (“red bag” delivery) meets this description, retention of the fetal membranes—an abnormality of stage III of labor—is not generally regarded as being a dystocia in the veterinary context. The terms malpresented fetus and malpositioned fetus are often used erroneously when the intent is to convey that the fetal head and/or neck—or one or more limbs—was not correctly aligned within the birth canal. It may be preferable to note that the fetus is maldisposed (fetal maldisposition) because this is an all-encompassing term that implies any combination of abnormalities—in presentation, position, and/or posture.3Presentation describes the orientation of the fetal spinal axis to that of the mare and also the portion of the fetus that enters the vaginal canal first (cranial or caudal longitudinal; ventrotransverse or dorsotransverse). Although the words anterior and posterior are still widely used in the veterinary literature, the correct Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria terms are cranial and caudal. Position describes the relationship of the fetal dorsum (longitudinal presentation) or head (transverse presentation) to the quadrants of the mare’s pelvis (dorsosacral, right/left dorsoilial, dorsopubic; right/left cephaloilial). Posture pertains to the fetus itself and describes the relationship of the extremities (head, neck, limbs) to the foal’s body. Postural abnormalities can be difficult to correct due to the remarkably long head, neck, and limbs of the foal. Repulsion describes the procedure whereby the fetus is repelled from the pelvic inlet such that the increased space in the uterus can be used to correct the maldisposition.4Mutation is an obstetrical term that is used to describe manipulation of the fetal extremities, together with correction of any positional abnormalities, such that assisted vaginal delivery can proceed. Version is the manual changing of the polarity of the fetus with reference to the mother. It is the manipulation that is employed when attempting to correct a transverse presentation. The head and forelimbs are repelled into the uterus, while the hindquarters are pulled into the pelvic canal.4 Tocolytic agents (clenbuterol, isoxsuprine) inhibit myometrial contractions. These agents are administered by injection in many countries to relax the uterus and thus provide more space for obstetrical manipulations.4,5

THE PREPARTUM MARE

A ventral, edematous plaque of variable thickness (2 to 4 inches) may develop in late gestation. The increased weight of the gravid uterus affects lymphatic drainage and venous return from the ventral abdomen. This physiologic phenomenon must be differentiated from the painful inflammatory edema that is associated with impending—or actual—ventral body wall rupture (prepubic tendon, ventral hernia). In these cases the mare may be reluctant to move, the mammary secretions will often contain blood, and ultrasonography can demonstrate tearing and edema within the musculature. A canvas abdominal sling may provide sufficient support to permit some of these mares to carry the foal to term.1

Changes in the hormonal milieu during the last weeks and days of gestation result in physical changes in the mare—but the signs of impending parturition are quite variable between mares. Relaxation of the sacrosciatic ligaments may cause a discernible hollow to develop on either side of the tail head, especially in older mares. This change may not be evident in a well-muscled mare. Even when visible relaxation is not apparent, a palpable softening of the ligaments may be detected. Any elongation and relaxation of the vulva tends not to be noticeable until foaling is imminent. The most notable change is usually in the mammary gland. The pregnant mare’s udder may start to increase in size during the last 4 to 6 weeks of gestation, and it generally becomes prominent within 2 weeks of foaling. The size of the udder is influenced by the parity of the mare, and some maiden mares will foal with minimal mammary changes. The onset of secretory activity is quite variable and cannot be used as a reliable indicator of impending parturition. Some mares may be observed to develop waxlike material on the teat orifices (“wax up”) several days before foaling, whereas others may never develop these honey-colored beads of dried secretion on the teat orifices. The teats usually fill with colostrum 24 to 48 hours before foaling, but some mares may drip or “run” milk for several days before the onset of parturition. In these cases a substantial volume of colostrum may be lost, and plans should be made to supplement the foal’s immunoglobulin intake. Electrolyte changes in mammary secretions can be used to predict “readiness for birth” if an observed parturition or a planned cesarean section (e.g., pelvic callus) has become necessary.6–8 However, these electrolyte changes are not a reliable indicator of fetal maturity if a placental anomaly is present (e.g., placentitis, twins).

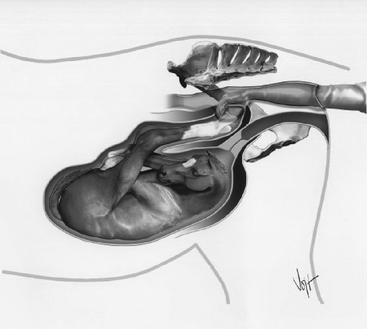

By late gestation, the orientation of the uterine horns has changed dramatically, with the horn containing the hindlimbs coming to rest on the dorsal surface of the uterine body, with the tip of the horn directed towards the cervix.9,10 Close to term the uterine body and gravid horn form what can be described as a U-shaped tube that tapers towards the tip. In some cases it is possible for the hindlimb hooves in the horn tip to be pushed so far caudally that they actually come to lie over the fetal head. Thus, when performing a per rectum evaluation of the pregnancy close to term, the fetal hooves that are palpable may sometimes be attached to the hindlimbs (Figure 59-1). Vigorous pistonlike thrusts of the hindlimbs, in association with elevation of the fetal rump, can result in the hooves being pushed well past the cervix into the rectogenital pouch.9–11 This observation may explain the acute colic episodes that have been previously attributed to uterine dorsoretroflexion.5 Although the gel-like pads on the fetal hooves may serve to protect the placenta and uterine wall from the vigorous activity of the hindlimbs, tears at the tip of the gravid horn can still occur during an unassisted foaling.10,12–14

A classic radiographic study demonstrated that the full-term equine fetus is lying in a dorsopubic position with the head, neck, and forelimbs flexed.15 Although the caudal aspect of the fetus is in a dorsopubic position and intimately associated with the ventral uterine wall, the cranial portion has room to rotate within the uterine body itself. Recent ultrasonographic studies have shown that in a mare close to term (>330 days of gestation) the cranial aspect of the fetus may be in dorsopubic position approximately 60% of the time and in dorsoilial position during about 40% of observations. Although the forelimbs and neck are usually flexed (about 80%), on some occasions the head or limbs may be extended.10,11 Thus palpation of the fetus cannot be used to detect impending dystocia (postural or positional complications) unless labor is already well advanced. However, if a transverse or caudal presentation is suspected, then a detailed transabdominal ultrasonographic evaluation is indicated to confirm the location of the fetal thorax and head. In both cases planned intervention may be warranted. In some cases transabdominal ultrasound may suggest that a fetus is transversely presented, yet the foal will be delivered normally. The so-called “body pregnancy” tends to cause abortion in the latter stages of gestation when the nutritional demands of the growing fetus are no longer being met. In these cases the placenta is underdeveloped and is characterized by the presence of short horns. It is this lack of development of a gravid horn that causes intrauterine fetal growth retardation and abortion due to placental insufficiency.16,17

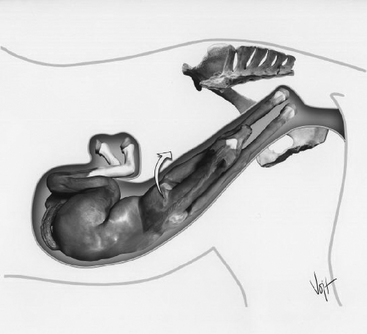

Until recently it has been difficult to explain how 98.9% of foals are delivered in cranial presentation, with 1.0% being caudal, and only 0.1% being transverse.3,18 A complex mechanism involving entrapment of the fetal hindlimbs within a uterine horn may be the answer. In early pregnancy, fetal rotation within the amniotic cavity and amniotic sac rotation within the allantoic cavity result in the characteristic twisting of the equine umbilical cord.19–21 Between 5 and 7 months of gestation it appears that contraction of the horns serves to confine the allantoic fluid and fetus to the uterine body.9–1120,22 It has been theorized that neurologic signals within the maturing inner ear may orient the dorsum of the fetus with the concave slope of the ventral uterine wall and prompt it to lie with the cranial aspect elevated towards the cervix.9–11,2223 The acute angle between the horn and body by 7 months of gestation means that the fetus must be in dorsal recumbency before the hindlimbs can gain entry. After 9 months the hindlimbs remain enclosed within the uterine horn, and the hooves reach to the tip by the tenth month.9–1120,22 Although the fetus is then locked into a cranial presentation and dorsopubic position, it is possible for the entire pregnancy (uterus and fetus) to rotate approximately 90 degrees on the lower maternal abdominal wall. This occurs because any rotational movement of the caudal half of the fetus (pelvis and hindlimbs) by necessity will involve the close-fitting uterus. In extreme cases this rotation may progress into a clinical uterine torsion.1,10,24

NORMAL PARTURITION

The first stage of parturition is characterized by the development of coordinated uterine contractions. The increased uterine pressure pushes the chorioallantoic sac (in the region of the cervical star) against the hormonally relaxed cervix such that gradual dilation occurs. Mares vary in their display of symptoms that are consistent with the onset of first-stage labor. In some the increasing intensity of the uterine contractions may be manifest by restless behavior similar to that of mild colic. Patchy sweating often develops, and some mares expel colostrum. The mare may look at her flank, frequently lie down and get up, stretch as if to urinate, and pass small amounts of feces.4 In some mares a normal delivery may be preceded by one or more episodes of false labor. Although the fetus probably determines the day, the mare appears to be able to choose the hour for delivery. It is not uncommon for labor signs to abate if the mare is unduly disturbed by the external environment. Thus it is important that supervision of foaling mares be unobtrusive. Any untoward activity may lead to a stress response and suppression of uterine contractions—especially in nervous mares.

It has been proposed that the increasing uterine tone during stage I of parturition somehow stimulates the fetus to extend its head and forelimbs.10 The fetus plays an active role in positioning itself for delivery and makes purposeful movements such that the cranial aspect rotates through a dorsoilial position as the head and forelimbs are extended up into the birth canal15 (Figure 59-2). The characteristic side-to-side rolling each time the mare assumes lateral recumbency is thought to assist in positioning the foal correctly. Dystocia cases that involve a dorsopubic position with flexed extremities suggest that the fetus was compromised before the start of the parturient process. Such a fetus would not actively participate in the foaling process.4,10,15,25 In some cases this may be indicative of advanced placentitis or fetal infection, and thus submission of tissue from a stillborn fetus and attendant membranes is recommended.16 The neck and forelimbs will not normally be returned to a flexed posture once a viable fetus in stage I of delivery has actively extended them. However, fetlock flexion can develop if the hoof catches on the pelvic brim or on a fold of vaginal mucosa. Continued expulsive efforts from the mare can force the carpus to flex as well.4 The onset of stage II is heralded by rupture of the chorioallantois and discharge of the watery allantoic fluid. This occurs when the fetlocks—and sometimes the knees—are at the level of the external cervical opening.10

While the cranial aspect of the foal is passing through the birth canal, the hindlimbs remain locked within the uterine horn. The second stage of labor is characterized by strong abdominal contractions that provide the expulsive force necessary to expel the fetus. Preexisting defects in the abdominal musculature (prepubic tendon rupture, ventral hernia) adversely affect the mare’s ability to mount sufficient intraabdominal pressure to expel the foal without assistance. These mares warrant close supervision because traction may need to be applied to the foal’s forelimbs once stage II of labor has commenced.1 Passage of the foal into the pelvic inlet initiates a reflex release of oxytocin from the posterior pituitary, thereby enhancing uterine contractility.4 Most mares assume lateral recumbency once active straining commences, although it is not uncommon for the mare to get up once or twice during second stage labor. Appearance of one hoof within the translucent fluid-filled amnion at the vulva lips can be expected to occur within 5 minutes of rupture of the chorioallantois.26 A dark yellowish green discoloration of the amnion and fluid is indicative of passage of meconium due to fetal stress. One forelimb should precede the other by several inches, such that the shoulders enter the pelvis successively. The measurement across the shoulders represents the widest portion of the foal. Thus the tendency for one limb to advance ahead of the other ensures that the cross-sectional diameter of the fetus at the shoulders is reduced. The soles of the hooves should be directed downward and the foal’s head should be resting between the carpi, with the muzzle reaching the proximal metacarpus. By the time the nose reaches the vulva the cranial half of the torso has already rotated from a dorsopubic to a dorsoilial position. The foal’s withers continue to rotate into a dorsosacral position as the head appears through the vulvar lips.10 At this time the foal’s shoulders have entered the pelvic canal.

Second stage labor in the mare is rapid, with the most forceful contractions occurring as the fetal thorax passes through the pelvic cavity. The amniotic sac may rupture during these expulsive efforts. However, the foal can be delivered with a portion of the sac wrapped around its head.26 Although a viable foal should be able to free itself of the fetal membranes, foaling attendants should be instructed to free the foal’s head promptly to avoid the possibility of suffocation. The fetal pelvis rotates through a dorsoilial position into a dorsosacral position, and the hindlimbs become extended as the fetal abdomen begins to pass through the vulvar lips. This occurs because at this point the stifles impinge upon the pelvic brim. The foal’s rump remains closely apposed to the cranial dome of the uterine body as the contracting uterus and abdominal press combine to expel the foal. Thus at the time of the foal’s delivery the cranial aspect of the uterine body is only about 12 inches from the cervix.10 Forceful straining ceases once the foal’s hips are delivered, and most mares will rest in lateral recumbency for several minutes. An active foal will extract its hindlimbs as it struggles to stand.

Most foals are delivered within 20 to 30 minutes after the chorioallantoic membrane ruptures. Primiparous dams generally require longer to expel the fetus than multiparous dams.4,26 Delayed delivery (prolonged foaling time) increases the likelihood of fetal asphyxia or neonatal problems associated with hypoxia due to placental separation.16,27 Often these losses occur in mares that were unattended at the time of foaling. The short, explosive birth process and the mare’s tendency to foal at night increase the probability of unattended delivery.27 Prepartum mares warrant close attention because careful monitoring of parturition may help to reduce the incidence of deaths attributable to neonatal asphyxia. A number of foaling monitors and video camera systems are available to alert personnel that foaling is imminent.28 Attendants should suspect that the mare is experiencing obstetric problems if either the first or second stage of parturition is prolonged or not progressive. Occasionally the chorioallantois fails to rupture, and the velvety, red membrane (“red bag”) appears at the vulvar lips (Figure 59-3). This is a common complication of induced parturition, and placental edema is a major problem in mares that have been exposed to endophyte-infected fescue hay or pasture.29,30 In the latter scenario the pregnancy may be prolonged, and the mare is also likely to be agalactic. Premature separation of the placenta is an emergency situation because the foal is deprived of its maternal oxygen supply. Foaling attendants should be instructed to break the membrane and to provide gentle traction in unison with the mare’s expulsive efforts. Although the foal should be delivered as quickly as possible, injudicious traction at this time can create a laceration in an incompletely dilated cervix.2

Experienced personnel can save many foals by early recognition of dystocias and by prompt intervention before serious complications arise. Signs that a mare may be experiencing difficulties include failure of any fetal parts or the amniotic membrane to appear at the vulvar lips within 5 minutes after rupture of the chorioallantois. If there is no evidence of strong contractions, and/or no progression in the delivery process within 10 minutes of rupture of the chorioallantois, then a vaginal examination is warranted. Other causes for concern are hooves upside-down or any abnormal combination of extremities appearing at the vulva (only one limb, hooves and nose in abnormal relationship, nose but not hooves, both forelimbs protruding but no head visible at the level of the carpi).26 The most common impediments to delivery are malpostures of the long fetal extremities (head and neck, or limbs).3,4,25 Failure to quickly identify a dystocia often results in the fetus becoming impacted in the birth canal by the mare’s uterine contractions and strong abdominal straining. The secret to foal survival is a combination of experience and expediency. If farm personnel are experienced and referring veterinarians are well trained in dystocia management, prompt referral to a hospital in close proximity may permit delivery of a viable foal—even after an hour has elapsed since the chorioallantois ruptured.31 It is probable that limited intervention causes less disruption of the fetal membranes and thus permits longer placental support of the fetus.

ASSESSMENT OF A DYSTOCIA CASE

The incidence of dystocia varies among breeds, with estimates ranging from 4% in Thoroughbreds to as much as 1 in 10 foalings in the heavily muscled Draft breeds. Hydrocephalus can occur in all breeds. Ponies are more likely to experience difficulties due to a large fetal skull that may resemble hydrocephaly in some cases.3,32,33 Irrespective of the likelihood of being requested to provide obstetrical assistance to a mare, it is prudent for an equine practitioner to have a well-organized dystocia kit readily accessible for such occasions during the foaling season. Supplies necessary to provide cardiovascular and respiratory support to a compromised neonate should always be available. All equipment should be clean and preferably sterile. A nasogastric tube, pump, and bucket should be kept exclusively for delivering volume-expanding lubricant (e.g., carboxymethylcellulose) into the uterus. This is especially important in those countries (e.g., the United States) where injectable tocolytic agents (clenbuterol, isoxsuprine) are not available for obstetrical use.4 Obstetrical chains, nylon ropes and handles are the basic requirements, and blunt eye hooks may occasionally be indicated.2,4,34 A detorsion rod, an obstetrical snare, and a Kuhn’s crutch repeller (with long nylon rope) can be useful in some instances—but require additional expertise.4,35 These metal instruments can easily traumatize the reproductive tract and should be used with caution. Mechanical extractive devices can exert inordinate force and do not have a place in equine obstetrics. Fetotomy in the mare should be performed only by experienced obstetricians. Essential equipment includes a fetotome and threader (with brush), saw wire with handles, wire cutter, curved wire introducer, fetotomy (palm) knife, and a Krey hook.36,37 Any prior obstetrical experience that has been obtained by managing bovine dystocias will be invaluable when a veterinarian is faced with the long extremities and forceful straining that inevitably complicate the resolution of equine obstetrical cases. A minimum of two people should be available to assist the obstetrician: one to hold the mare’s head and at least one other individual to hold instruments and to assist with fetal delivery.

Dystocia in a mare should always be regarded as an emergency, especially if there is a possibility that the foal is still alive. Apart from potential loss of the foal, the mare’s future fertility is often compromised, and some may even suffer fatal complications. Upon arrival the veterinarian should make a cursory assessment of the mare’s general physical condition, noting in particular mucous membrane color and refill time (hemorrhage, shock).2 A more complete examination may be indicated once attempts have been made to deliver a viable fetus. Time is the critical factor when managing an equine obstetrical case.31 The perineal area should be inspected for the presence and nature of any vulvar discharge, the presence of fetal membranes, and to identify any fetal extremities. Excessive hemorrhage is indicative of soft tissue trauma. Moist fetal extremities may help to confirm that assistance was summoned promptly, whereas dry and swollen tissues are typical of more protracted cases. A malodorous discharge strongly suggests the presence of an emphysematous fetus, an uncommon occurrence that may be encountered in neglected cases.4 Occasionally a foaling mare may present with a rectal prolapse, an everted bladder, or with loops of bowel (small intestine, colon) protruding from the vulvar lips.2 While performing this external examination of the mare, the veterinarian should obtain the following information from the owner: age and parity number; expected foaling date; duration and intensity of labor signs; time since rupture of the chorioallantois; appearance of fetal membranes, limbs, or muzzle at vulvar lips; and whether any attempts at manual intervention have been made. It is not uncommon to be informed that the muzzle was present when an attempt was made to correct a simple limb malposture. Unfortunately these cases have often been complicated by a flexed head and neck posture before veterinary assistance is requested. Reports of fetal movement observed in the mare’s flanks are often unreliable, and the mare’s expulsive efforts can easily cause deceptive “movement” of exposed extremities in what is already a dead fetus.

The internal examination should be performed in a clean area with good footing and with sufficient room to ensure safety for all personnel involved. The use of rigid, closed-end stocks is contraindicated because of the propensity for parturient mares to become recumbent. However, adequate restraint is essential because the behavior of a mare in the second stage of labor is so unpredictable—and it can be violent. If used, the stocks should be open-ended with movable sides. Whenever possible, the initial examination should be performed on a standing mare in a large, well-bedded stall with nothing more than a twitch or lip chain for restraint. The person handling the mare should stand on the same side as the obstetrician and apply intermittent tension to the twitch or lip chain when instructed to do so. If the mare attempts to kick, the head should be pulled towards the handler such that the hindquarters will move away from the obstetrician. Although not essential, an initial rectal examination may rule out the presence of a term uterine torsion, may determine the condition of the uterine wall (tears, spasm), and may provide useful information regarding the disposition of the fetus.2,24 Before any vaginal examination the mare’s tail should be wrapped and the perineal area thoroughly cleansed. The clinician’s arms and hands should be scrubbed with disinfectant soap. The use of sterile sleeves is optional. The author routinely uses shoulder length rubber sleeves with surgical gloves attached. Although disposable plastic sleeves decrease tactile sensation, experienced obstetricians believe that the use of a sleeve reduces the amount of trauma inflicted upon the vaginal mucous membranes. Liberal application of lubricant is essential because the mare’s vagina and cervix are easily traumatized, and future fertility can be jeopardized by the resultant adhesions and fibrosis. White petroleum jelly (Vaseline) is useful when performing the initial exploratory examination. If there is evidence of prior vaginal manipulations, it may be prudent to perform an abdominocentesis to ensure uterine integrity before instilling large volumes of liquid obstetrical lubricant.14,38

A rapid, thorough check should be made for lesions, lacerations, and contusions of the genital tract. The presence of any pelvic abnormalities that may impede passage of the fetus should be noted, the degree of cervical relaxation determined, and an assessment made as to whether or not the uterus is tightly contracted around the fetus. Although fetopelvic disproportion is uncommon in the mare, it can be a factor in some equine dystocias, especially those in primiparous mares.16,27,39,40 The disposition of the fetus should be noted (presentation, position, and posture) and fetal viability determined.2 Care should be exercised because an active fetal response to manipulations can easily complicate what was initially a simple dystocia. This is often the cause of the more extreme head and neck malpostures.2,25,34 Placement of a rope snare behind the ears and into the mouth will ensure that the clinician always has control of the head. This will facilitate easy correction of a potentially life-threatening development such as lateral deviation of the head and neck if the fetus pulls away from the clinician’s arm. Although tension on the head snare can force the mouth open, it is unlikely that the incisors will have broken the gum sufficiently to be of concern. Nevertheless, care should be taken to protect the uterus from the exposed incisors if retrieval becomes necessary. A mandibular snare will also suffice, but this should be used only to guide the head back into the pelvic canal. Excessive traction can easily cause a mandibular fracture.4

When obvious fetal movement is absent, limb withdrawal may be initiated in response to pinching of the coronary band. Slight digital pressure through the eyelid may arouse a response, as may stimulation of the tongue (swallowing). If the thorax can be reached, fetal heartbeat is definitive. In caudally presented cases, the digital and anal reflexes are useful as indicators of fetal viability.2,4 Failure to elicit a response is not always an absolute confirmation of fetal death. When there is doubt about fetal viability, an ultrasonographic assessment of the fetal heart may be made with a 3.5-MHz transabdominal probe. If the fetus is in an abnormal position, the clinician should investigate the possibility of a term uterine torsion.24 Once the cause of the dystocia has been determined, the obstetrician should ensure that the owner understands the various treatment options and costs and the inherent risks that may be associated with each approach. The prognosis for survival of both the mare and foal and the impact of the treatment options on the mare’s future fertility should also be discussed. Sometimes the owner will place more value on the mare’s nonreproductive attributes, whereas in other cases the mare’s future fertility is of paramount importance. The economics of the case, the expertise of the clinician, and the proximity of hospital facilities are all factors to be considered when planning the best course of action to resolve a dystocia case.2,31,34,36,41,42 Prolonged vaginal manipulations are contraindicated if future fertility is an objective. The mucous membranes are easily abraded and will inevitably heal with transluminal adhesions and fibrosis. Repeated insertion and removal of the obstetrician’s arm not only traumatizes the vaginal canal and cervix, but also increases the bacterial load that is carried into the uterus. The clinician must be decisive, and if a brief manipulation is ineffective, then an alternate approach should be considered. One or two fetotomy cuts will often permit rapid, atraumatic extraction of a dead fetus, provided that the obstetrician is experienced in the technique.36,37 Unfortunately, fetotomy is often used as a last resort when prolonged manipulations have failed to correct the problem, and extensive soft tissue trauma has already been inflicted. If a well-equipped veterinary hospital is close by, then immediate referral for general anesthesia, controlled vaginal delivery, or cesarean section may offer the best prospect for foal survival and the mare’s subsequent fertility.31,41

CHEMICAL RESTRAINT

The choice of restraint will vary with the obstetrician and will be determined by such factors as the mare’s demeanor, the complexity of the dystocia, and the expectation of fetal viability. If delivery of a live foal is anticipated, the clinician should consider the potential for altered placental perfusion and fetal cardiovascular compromise before administering any tranquilizers to the mare. Light sedation with acetylpromazine should have minimal effect on the foal. If extra restraint is required, xylazine is preferable to detomidine if the fetus is viable because its depressant effects are of much shorter duration. Neither xylazine nor detomidine should be used on its own to sedate a dystocia case because some apparently sedated mares can become hypersensitive over the hindquarters. A xylazine-acepromazine combination will provide good sedation in a quiet mare, but a xylazine-butorphanol combination may be preferable if extra sedation and analgesia is necessary. Reduced dosages should be used initially, especially in Draft breeds and miniatures that appear to respond more intensely to tranquilizers and sedative-hypnotic drugs than light breeds. Because opioid analgesics can cause some gastrointestinal stasis and impaction, it is especially important to administer mineral oil once the dystocia has been resolved if these agents have been used.43,44

The time involved in administering effective epidural anesthesia often makes this form of restraint impractical if a live foal is to be delivered. The majority of fetotomy procedures (one or two cuts) can be made on a standing mare, and in these cases, caudal epidural anesthesia may be used at the clinician’s discretion. Although an epidural does not prevent the mare’s myometrial contractions or the abdominal press, it will reduce vaginal sensitivity and thus suppresses the Ferguson reflex associated with vaginal manipulations.4,43 If an epidural is used, a xylazine-lidocaine combination is recommended. A low dose is essential to avoid the complication of ataxia, especially if referral to a hospital is a possibility.45 Myometrial contractions (uterine spasm) can be controlled by injectable tocolytic agents (isoxsuprine, clenbuterol) if they are available for veterinary use.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree