Sameeh M. Abutarbush

Dysphagia

Dysphagia is not uncommon in equine practice. It has numerous causes that can be congenital or acquired, the primary problem or part of a multisystemic condition or disease, or a manifestation of a muscular or neurologic disease. The diagnosis can be challenging, and proper early management is important in most cases.

The word dysphagia originates from the Greek dys (disordered, painful, or difficult) and phagein (to eat). Equine clinicians usually use the term dysphagia to describe a set of clinical signs rather than a mechanism or location of the problem. Dysphagia has several, slightly different definitions in the veterinary literature. Some define it as difficulty in swallowing or inability to swallow, others as difficulty in eating, and some as both. However, it is important to note that dysphagia is the inability and not the unwillingness to eat. The definition used in this chapter is difficulty in prehension, mastication, or swallowing.

Pathophysiology, Causes, and Clinical Signs

Prehension

The lips, which have a major role in prehension, are well innervated, are highly vascular, and move constantly as they grasp the feed, which is then severed by the incisors. The cerebral cortex and basal nuclei control the voluntary effort of prehension centrally; motor output is through the buccal branch of the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII), and sensory input is through the trigeminal nerve (V). Consequently, inability to prehend feed may be a result of problems in the lips, incisors, jaws, and buccal muscles or may be associated with central or peripheral nervous system lesions.

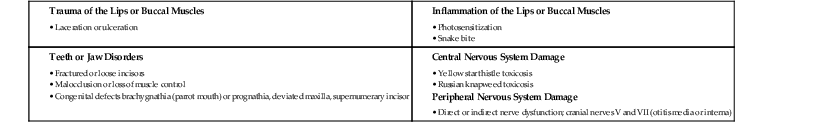

Causes and conditions associated with difficulty in prehension are summarized (Box 85-1). Affected animals are usually able to swallow but unable to grasp feed and move it aborally. Clinical signs of dysphagia associated with a problem in prehension include drooling of saliva, feed dropping from the mouth, and attempts to prehend by grasping the feed with the teeth and tossing the head to try to move the feed back into the mouth. Horses having trouble with prehension also submerge their nose to the level of the pharynx when drinking. Loss of sensation of the lips, droopy lips, or accumulation of feed in the buccal cavity may also occur if there is dysfunction of cranial nerves V and VII.

Mastication

Premolars, molars, and the muscles of chewing (innervated by cranial nerves V and VII) are required for mastication. The buccinator muscle prevents the feed from accumulating in the buccal pouches, and the salivary glands produce saliva for softening the feed and initial digestion. Although salivation is under parasympathetic control, saliva flows from the parotid salivary glands only during rhythmic mandibular motion.

Clinical signs of dysphagia resulting from abnormal mastication include prehension with no attempts to chew, refusal to open the mouth, excessive salivation, and sometimes a fetid odor to the breath. The horse is interested in feed when offered and can get the feed into the mouth, but then hesitates and allows the feed to fall out of the mouth.

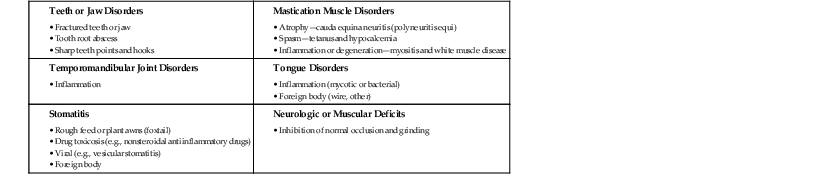

Dysphagia caused by a problem in mastication is usually related to abnormality in the teeth (most commonly), tongue, jaws, or temporomandibular joint (Box 85-2). Pain, neurologic deficits, or muscular deficits that inhibit normal occlusion and grinding movements of the mandibular and maxillary teeth can all cause difficulty in mastication.

Deglutition

Swallowing (deglutition) is divided into oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal stages. Swallowing is initiated when material is delivered to the pharynx. The feed bolus forms in the oropharynx and is moved by the tongue through the pharynx; respiration is suspended, the soft palate elevates and seals off the nasopharynx, and the epiglottis apex retroverts. This sequential process protects the larynx and upper and lower airways. Next, the caudal musculature of the pharynx contracts craniad to the bolus. The upper esophageal sphincter relaxes to receive the bolus and then contracts craniad to it to prevent the bolus from returning to the pharynx. In the esophageal phase of swallowing, after the passage of the bolus to the proximal part of the esophagus, primary peristaltic waves are initiated to carry the bolus to the cardia. The coordinated swallowing movements involve the tongue, which is suspended on the hyoid apparatus and innervated by the hypoglossal nerve (XII), and the larynx and pharynx, which are primarily controlled by the nucleus ambiguus and nucleus solitarius in the caudal brainstem through the glossopharyngeal (IX), vagus (X), and accessory (XI) cranial nerves.

In most cases of inability to swallow, the condition starts gradually, over a period of hours or days. Initially, the horse may attempt to eat or drink. Restlessness, gagging, paroxysms of coughing, saliva and feed falling from the mouth, and nasal reflux of saliva, ingesta, or feed may be observed. Impaction of the feed in the pharynx can sometimes cause stridor; in chronic cases, fetid breath and weight loss can occur. Inability to swallow is mainly caused by neurologic, mechanical, or iatrogenic conditions (Box 85-3).