Chapter 4 Disorders of the Urinary and Reproductive Systems

Disorders of the Urinary System

The ferret has a classic bean-shaped kidney that sits in the retroperitoneal space; its dorsal surface lies in direct contact with sublumbar musculature.21 Renal pathology is a common necropsy finding in ferrets,25,31 whereas renal disease, such as renal failure, cystitis, and urolithiasis, is uncommon in the pet ferret. The only exception is prostatic disease, which is relatively common in the United States, because of the high prevalence of adrenal disease.

Renal Cysts

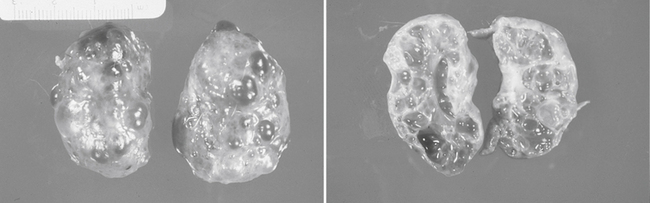

Renal cysts are a common incidental finding in ferrets. At one institution, cysts were found in 10% to 15% of ferrets submitted for necropsy.25 Renal cysts were detected sonographically at percentages ranging from 31.6% to 62.8% of ferrets.27,31,59,60 Renal cysts may range from 1 to 25 mm in diameter.19,38,69 They are usually present singly or in small numbers and can be present in one or both kidneys.20 Cysts are commonly found in the cortices, in close relationship to the pelvic recesses.59,60 The cause of renal cysts in ferrets is uncertain. There is no known hereditary basis for cyst formation, but they are thought to be congenital.60

Renal cysts may be detected during physical examination (as one or more smooth masses on the renal surface), during sonographic examination (as smooth-walled, hypoechoic areas), or grossly (as translucent swellings visible through the renal capsule). Cysts may pit the kidney surface creating a wedge of cortical pallor and renal congestion.31

There is no specific treatment for renal cysts. Monitor affected ferrets with periodic palpation and, if clinically indicated, ultrasound examination, serum biochemical analysis, and urinalysis. In humans, simple cysts are usually clinically silent, although they occasionally hemorrhage and cause acute pain.10 If a cyst becomes very large or painful, consider unilateral nephrectomy; however, be sure the contralateral kidney is functioning adequately before surgery.

Polycystic Kidney Disease

The quantity, location, and size of the typical ferret renal cyst are very different from polycystic kidney disease,60 which is rare in ferrets. Unlike the smooth masses palpable with renal cysts, polycystic kidneys are palpable as slightly irregular, enlarged, firm, oval masses that may grossly appear pale to tan or gray in color.21,31 Cysts may also be diffusely distributed throughout other parenchyma, particularly the liver.

If sufficient renal architecture is disrupted, cysts will lead to renal failure (Fig. 4-1). Ferrets may have anorexia, weight loss, lethargy, and signs of gastrointestinal dysfunction.21 Use ultrasonography or intravenous pyelography to confirm disease. Unilateral nephrectomy carries a good prognosis if function of the remaining kidney is normal. Assess the contralateral kidney using CBC, serum biochemistry analysis, and urinalysis.

Several renal cysts were found at necropsy in an adult ferret with seizure activity. Neurologic signs were presumed to be caused by uremic encephalopathy, although the brain was unavailable for examination.15 In a second case report, polycystic kidneys and bilateral perinephric pseudocysts were reported in an adult ferret. Pseudocyst formation led to marked abdominal distention and tachypnea. Ultrasound-guided paracentesis was used initially as a palliative treatment, but fluid reaccumulated rapidly. Although plans were made to resect the renal capsule, the ferret declined rapidly and was euthanatized instead.57

Hydronephrosis

Hydronephrosis and hydroureter are uncommon findings in ferrets usually attributed to ligation of the ureter during ovariohysterectomy.46 There have also been rare reports of hydronephrosis associated with obstruction caused by ureteral calculi, carcinoma involving the renal pelvis, and cystitis and herniation of the bladder.9,37,53

Renal Disease and Renal Failure

Chronic Renal Failure

Variable degrees of chronic interstitial nephritis are commonly found at necropsy in ferrets older than 4 years of age.20,31,35 Advanced interstitial nephrititis, as well as pyelonephritis, glomerulonephritis, bilirubinuric nephrosis (C. G. Pollock, personal observation, 2003), and immune complex–mediated glomerulonephropathy caused by Aleutian disease (see discussion later in this chapter), can cause renal failure.54 Use of nephrotoxic drugs may also result in renal disease, and renal failure has also been reported as a result of an epinephrine overdose given to a ferret with a vaccine reaction.16 Although uncommon, renal tumors are another potential cause of renal failure in ferrets.9

Acute Renal Failure

The most common cause of acute renal failure (ARF) in the ferret is urethral obstruction secondary to prostatic disease or, less commonly, urolithiasis.21,40 Another important, but uncommon, cause of ARF is toxic exposure. The minimum lethal dose of ibuprofen is 220 mg/kg, which means that ingestion of one tablet could be fatal in a small ferret. Clinical signs appear within 48 hours of ibuprofen ingestion and as rapidly as in 4 hours in 40% of ferrets. The most common clinical signs are neurologic, and more than half of ferrets also have gastrointestinal signs. Renal signs may include polyuria and polydipsia. In rare instances, acetaminophen ingestion may also cause ARF.17

Diagnosis and Treatment

Abnormal serum biochemistry results may include hyperphosphatemia, hyperkalemia, reduced total carbon dioxide levels, and azotemia. Interestingly, increases in serum creatinine levels are relatively moderate (generally less than 2 mg/dL). Kawasaki35 described two ferrets with severe renal disease confirmed by histologic examination; both ferrets had a creatinine level of 1.1 mg/dL in conjunction with blood urea nitrogen values of 140 and 320 mg/dL. The reported normal mean creatinine level in ferrets is lower (0.4 to 0.6 mg/dL) and the range is narrower (0.2 to 0.9 mg/dL) than in cats and dogs.19,23

Reference values have been established for endogenous and exogenous creatinine and insulin clearance tests used to evaluate glomerular filtration in ferrets.18,19 Although reference values for urine protein/creatinine ratios (UP:C) have not been established for ferrets, UP:C accurately reflects protein excretion in cats and dogs over a 24-hour period regardless of sex, urine collection method, time of day, or whether the animal has been fasted or fed. Canine reference values are generally less than 1.0 and cats are less than 0.6.68

If renal disease is diagnosed, attempt to identify the underlying cause with ultrasound examination and, if necessary, ultrasound-guided renal biopsy (as in cats). Sonographically, healthy ferret kidneys show a median resistive index (RI) of 0.54 ± 0.04 and a median pulsatility index (PI) of 0.83 ± 0.10. Even with severe renal parenchymal changes no significant alterations in blood flow parameters are seen; however, these indices do increase with age. Interestingly, male ferret kidneys have significantly higher blood flow velocities than females.32 At necropsy, kidneys with significant disease are often grossly pitted with large, focal depressions in the outer cortex secondary to scarring.21

Although treatment should be aimed at the underlying cause, nonspecific therapy of renal failure includes supportive care such as vitamin and iron supplementation, nutritional support, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation, erythropoietin for anemia, and fluid therapy. Normal daily fluid intake is estimated to be 75 to 100 mL/kg/day. Beware of overhydration in ferrets. Monitor patients for evidence of serous nasal discharge, tachypnea, or dyspnea and monitor body weight at least twice daily. Begin antibiotics if clinically indicated and use culture and sensitivity results when available. Discontinue any potentially nephrotoxic drugs,21 and administer phosphate binders and diuretics as needed. The use of small animal renal diets is difficult to impossible in ferrets since most individuals do not find these products palatable. Furthermore, the effects of long-term protein restriction require study in the ferret. Lewington37 has proposed feeding ferrets with renal disease discrete meals instead of free choice.

The prognosis for ferrets with renal failure depends on laboratory findings and response to therapy.

Aleutian Disease

Many ferrets infected with the parvovirus that causes Aleutian disease are asymptomatic carriers. Clinical signs are usually consistent with chronic wasting and ataxia. Additional clinical signs may be attributed to immune complex deposition. Deposits in the kidney may cause membranous glomerulonephritis and tubular interstitial nephritis, and possibly renal failure. Aleutian disease virus (ADV) may also cause liver failure, intestinal disease including melena, and central nervous system disease.54 See Chapter 5 for diagnosis and treatment of ADV.

Nephrocalcinosis

In three separate sonographic surveys, hyperechogenicity of the renal medulla was seen in 40% to 58% of European pet ferrets.27,59,60 This sonographic finding was not identified in laboratory ferrets. Histologic evaluation showed calcium deposits in the renal tubules consistent with renal calcification. Crystalline structures within renal parenchyma that could not be found sonographically were believed to be urates. Dietary analyses suggested that the presumptive nephrocalcinosis was related to excess dietary calcium and phosphorus.60

Pyelonephritis

Pyelonephritis is an uncommon finding in the ferret usually associated with an ascending bacterial urinary tract infection or sepsis. Hemolytic Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus are the most common causative agents. Clinical signs include anorexia, lethargy, fever, and pain on palpation of the kidneys.20 Severe suppurative pyelonephritis progressing to end-stage chronic renal failure was reported in a ferret treated for lymphoma. Immunosuppression from long-term corticosteroid administration may have led to cystitis and secondary pyelonephritis.61

Renal Neoplasia

Renal tumors are very rare in the ferret.9,34,39 The most commonly reported primary tumor is renal pelvic transitional cell carcinoma.20 Other primary renal tumors reported include renal adenocarcinoma, renal adenoma, and papillary tubular cystadenoma.9 The kidney may also be the site of metastatic disease such as malignant lymphoma.39 Stage IV lymphoma invaded the kidneys in 8 of 18 ferrets in one survey.2

Primary renal tumors can be incidental necropsy findings since they tend to be slow growing with little metastatic potential.69 Clinical signs reported in a 7-year-old ovariectomized pet ferret with pleomorphic renal adenocarcinoma included hematuria, dysuria, and incontinence, as well as nonspecific signs of illness such as anorexia, lethargy, and weight loss. Abdominal effusion and peripheral lymphadenopathy were detected on physical examination, and metastases to the lungs and pleura were found at necropsy. The neoplasm consisted of a large, solid mass and a cyst measuring 3 cm in diameter.34

Diagnosis of renal tumors relies on abdominal palpation, urinalysis, and imaging. Renal tumors usually appear as cystic areas on ultrasound, and may initially be mistaken for renal cysts.69 Definitive diagnosis is achieved via ultrasound-guided needle biopsy or at necropsy.

Ureteral Rupture

Traumatic avulsion of the ureter was reported in a ferret with blunt trauma severe enough to also create a diaphragmatic hernia. No specific urinary tract signs or abnormal clinical pathologic findings were observed. Excretory urography was used to detect ureteral leakage, and treatment included ureteronephrectomy.69

Urolithiasis

Urolithiasis is characterized by solitary or multiple calculi found anywhere throughout the urinary tract or by the presence of sandy material within the bladder and urethra. Urinary calculi used to be a common cause of stranguria in ferrets; however, improvements in diet have made urolithiasis rare in ferrets on ferret food or high-quality cat food. Urolithiasis is also rare in working ferrets and pet ferrets on fresh meat diets in New Zealand, Australia, and Europe.37

The most common urinary calculus reported is magnesium ammonium phosphate or struvite. Dietary factors are believed to play an important role in struvite crystal formation. Urine pH is greatly influenced by diet, specifically by the source of dietary protein. Metabolism of animal protein tends to produce acidic urine, whereas plant-based protein diets, such as dog food or inexpensive cat foods, produce alkaline urine. Struvite crystals commonly form at urine pH exceeding 6.6. Significant crystalluria leads to the development of calculi or sandy material in the bladder and urethra. In one report, 6 of 43 ferrets (14%) fed dog food had renal or cystic calculi at necropsy.48

Urolithiasis is seen most commonly in adult males. Calculi may also be associated with ascending cystitis in pregnant jills, usually caused by urease-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus or Proteus species.8,37

Mixed uroliths have been reported in ferrets including 60% struvite and 40% calcium oxalate,14 and there are also rare reports of cystine stones.18,21 The cause of cystine urolithiasis in ferrets is unknown, but has been speculated to be dietary or hereditary.

Diagnosis

Affected jills may be asymptomatic or show intermittent straining for days or weeks. Eventually the jill will show real distress when cystic calculi reach a large size. By this time, there may be evidence of urine dribbling and possibly vulvar scald. Although urethral obstruction is most common in male ferrets, females can also become obstructed, potentially straining hard enough to cause rectal or vaginal prolapse and potentially fatal hemorrhage.8,37,52

In affected ferrets, submit samples for CBC, serum biochemistry analysis, urinalysis, and ideally urine bacterial culture and sensitivity. The reported range for normal ferret urine pH is 6.5 to 7.5.21 Urine should be more acidic in ferrets fed a high-quality, meat-based diet.

Therapy

Treatment of urinary obstruction in male ferrets is a challenge. Place a urinary catheter (see “Urethral Obstruction” later in this chapter), then flush the urolith into the urinary bladder for future removal via cystotomy.20

Convert the ferret to an animal protein–based diet. Because a ferret on a high-quality diet has a urinary pH of approximately 6.0, urinary acidifiers are usually unnecessary. Attempts to feed feline magnesium-restricted acidifying diets (e.g., feline s/d [Hill’s Pet Nutrition, Topeka, KS] or feline Urinary SO [Royal Canin, St. Charles, MO]) are generally unsuccessful. These diets probably also contain insufficient protein for long-term use in ferrets. Use of a protein-restrictive diet for advanced renal disease (Hill’s Prescription diet u/d) has been described for dietary management of cystine urolithiasis. The ferret was also fed a protein supplement and hemoglobin and albumin levels were monitored.18 Two cases of cystine urolithiasis in which owners did not modify diet postoperatively have also been reported. Calculi did not recur postoperatively.20

The prognosis is good for urethral or cystic calculi with aggressive treatment. The long-term prognosis for bilateral renal calculi is guarded.21

Cystitis

Spontaneous bacterial cystitis is rare in ferrets, although it is more common in jills than hobs. Bacteria commonly associated with cystitis include S. aureus, Proteus species, and E. coli. If cystitis is identified, screen the ferret for underlying disease such as adrenal-associated prostatomegaly (see later discussion) or urolithiasis (see earlier discussion). In rare instances, cystitis has also been associated with neoplasia such as transitional cell carcinoma.20

Obtain a sample for urinalysis and bacterial culture and sensitivity, ideally via cystocentesis. Urinalysis results may include hematuria, pyuria, bacteruria, and tubular casts. Normal ferret urine pH is approximately 6.0. CBC and serum biochemistry results are often unremarkable although an inflammatory leukogram may be seen with an ascending bacterial infection. Because primary cystitis is rare, consider survey abdominal radiographs, abdominal ultrasound, and adrenal hormone analysis to identify the underlying cause of infection.

Bladder Neoplasia

There are rare reports of transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder in ferrets. Initial signs are often subtle but may include hematuria, dysuria, polyuria, or incontinence. The urinary bladder may palpate abnormally, and excessive numbers of transitional cells, some abnormal in appearance, are seen on urinalysis. Use ultrasonography or contrast radiography to visualize bladder lesions. Definitive diagnosis is based on biopsy results. The prognosis is poor.58,69

Urinary Incontinence

True incontinence is rare in ferrets. More commonly, ferrets are treated for dribbling due to overfill of the urinary bladder as a result of urolithiasis or prostatomegaly. True incontinence may be associated with bladder neoplasia, severe cystitis, or Aleutian disease virus. Additionally, although rabies virus is extremely rare in domestic ferrets, bladder atony and incontinence were reported in 65% of experimentally infected ferrets.37,47

Urethral Obstruction

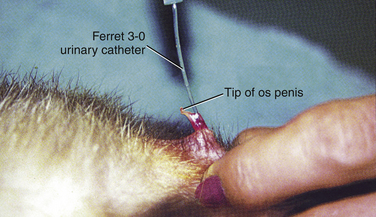

Urethral catheter placement is challenging in the male ferret due to its small size and J-shaped os penis (Fig. 4-2). Use general anesthesia to achieve adequate skeletal muscle relaxation. Mask induce ferrets with isoflurane or sevoflurane or administer etomidate (1 to 2 mg/kg intravenously [IV]) with diazepam (0.1 mg/kg IV) or propofol (4 to 6 mg/kg IV) with diazepam (0.25 to 0.5 mg/kg IV). After induction, intubate ferrets if jaw tone allows and maintain on inhalant anesthesia.40 Avoid ketamine because it is excreted by the kidneys. Provide supplemental heat and appropriate preemptive analgesia such as buprenorphine (0.01 to 0.03 mg/kg subcutaneously [SC], intramuscularly [IM], IV q8–12h), butorphanol (0.1 to 0.5 mg/kg SC, IM q4–6h or 0.025 to 0.1 mg/kg/hr IV), or fentanyl (2.5 to 5.0 μg/kg/hr IV).26,40

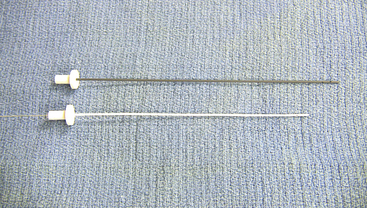

Whenever possible use a catheter designed for use in ferrets such as the 3.0-French 11-cm open-ended silicone catheter (Slippery Sam, Smiths Medical PM, Waukesha, WI) (Fig. 4-3).36 The Slippery Sam catheter is flexible with a rounded tip and fine flexible stylet to facilitate introduction into the distal urethra, which is difficult to visualize in this species (A. Lennox, personal communication, 2009). A 24-gauge catheter may also be used to identify and dilate the small, slit-like urethral opening. In addition to the Slippery Sam catheter, a 20- or 22-gauge 8-inch jugular catheter may serve as a makeshift urinary catheter, and a 3.5-French red rubber catheter may be placed in a large male (Fig. 4-4).43 Some clinicians routinely fit ferrets with an Elizabethan collar at the time of catheter placement. Secure the collar by criss-crossing gauze under the forelimbs in a figure-eight pattern.36 Patients alert enough to attempt to disrupt the catheter may also be maintained on low-dose opioids by injection or constant rate infusion (CRI) (M. Lichtenberger and A. Lennox, personal observation, 2009).

Carefully monitor the electrocardiogram for evidence of hyperkalemia such as loss of the P wave, widening of the QRS complex, and peaked T waves. Relief of obstruction and forced diuresis are usually sufficient in the management of hyperkalemia. Medical treatment is indicated if an arrhythmia is present in addition to poor perfusion or altered mentation. Give calcium gluconate (50 to 100 mg/kg slow bolus IV) or insulin (0.2 U/kg IV) with 50% dextrose (1 to 2 g per unit insulin IV).40

To provide additional relief for urethral obstruction, some clinicians use smooth muscle relaxants such as diazepam (0.5 mg/kg PO, IM, IV q6–8h), midazolam (0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg SC, IM), or, in rare instances, alpha-adrenergic antagonists such as phenoxybenzamine (Dibenzyline, SmithKline Beecham, Philadelphia, PA; 3.75 to 7.5 mg PO q24–72h) (D. Mader, personal communication, 2010). Use alpha-adrenergic antagonists with caution because of the potential for adverse gastrointestinal and cardiovascular effects.

Monitor urine production in catheterized ferrets using a closed line attached to a small (150 to 250 mL) IV bag. Urinary output must be at least 1 to 2 mL/kg/hr and with diuresis, urine production may be up to 140 mL/day.40 Maintain the urinary catheter for 1 to 3 days50 postoperatively while providing aggressive supportive care: correct metabolic and acid-base disturbances, and administer fluids to correct perfusion abnormalities and rehydrate the patient. Maintenance fluid requirements in ferrets are estimated at 75 to 100 mL/kg/day. Monitor patients carefully for signs of overhydration.

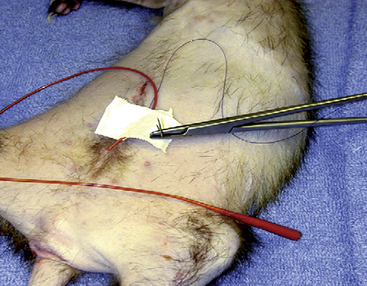

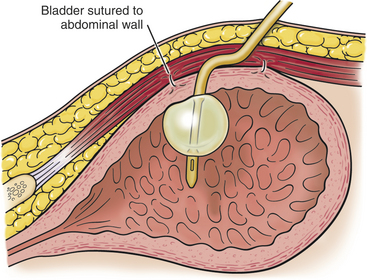

If attempts at urinary catheterization are unsuccessful, consider cystocentesis to help stabilize the patient preoperatively,7 although there is some risk of urinary bladder rupture and uroabdomen.40 Perform an exploratory laparotomy and emergency cystotomy if needed. If normograde passage of a urinary catheter is unsuccessful, an emergency perineal urethrostomy is required. Tube cystostomy has also been described in ferrets with urinary obstruction (Fig. 4-5) (see Chapter 11).49

Prostatic Cysts

The prostate is the only accessory reproductive gland of the ferret. Whereas the canine prostate is a compact, relatively prominent enlargement, the ferret prostate is a small, fusiform mass measuring approximately 15 mm long by 6 mm wide. The ferret prostate surrounds the neck of the bladder and the proximal urethra, and is surrounded by a fibromuscular capsule from which numerous septae extend.25,30,38,50

Prostatic disease is the leading cause of urinary tract disease and urethral obstruction in middle-aged to older male castrated ferrets.52 Neutering of ferrets is routinely performed at 6 weeks of age in the United States,39 and adrenocortical disease in the ferret has been correlated with early gonadectomy. Adrenal tumors in gonadectomized ferrets are theorized to be due to chronic stimulation by luteinizing hormone.66

Outside of the United States, most ferrets are gonadectomized at several months of age, and adrenal disease is relatively uncommon. Prostatic disease is also uncommon in the intact hob.20 There are rare reports of prostatic disease associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder.21

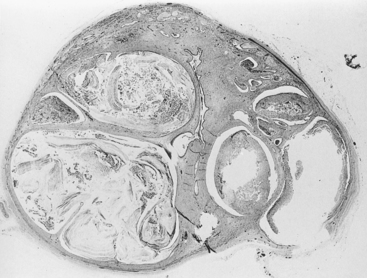

Adrenocortical disease in the male ferret is associated with the development of sterile prostatic cysts. Although the exact pathogenesis is unclear, elevated circulating sex steroid hormone levels appear to stimulate proliferation of prostatic tissue (see Chapter 7).12 Low to moderate numbers of neutrophils and fewer lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells may infiltrate glandular tissue.12 Squamous metaplasia of prostatic ductular epithelium causes the prostate to expand with multiple, fluid-filled cysts of various sizes filled with keratin, neutrophils, and proteinaceous debris (Fig. 4-6). Prostatic cysts can measure up to 1 cm in diameter and they can compress the urethra, leading to urine stasis.12 Extensive prostatomegaly leads to urethral obstruction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree