Chapter 29 DISORDERS OF THE TESTES AND EPIDIDYMIDES

CONGENITAL DISORDERS

Cryptorchidism

NORMAL DESCENT.

The first event in the sexual differentiation of the fetus is the differentiation and development of the gonads. The chromosomal sex normally determines gonadal sex. Testicular differentiation is controlled by the Y chromosome. The lack of a Y chromosome results in development of an ovary. The sex-determining region Y gene, SRY, is normally located on the Y chromosome. This gene encodes the testis-determining factor and is the genetic signal for initiating testis differentiation (Sinclair et al, 1990; Goodfellow and Lovell-Badge, 1993). SRY is distinctly different from the gene for H-Y antigen, which is no longer thought to have a role in testis induction (Koopman et al, 1991). Once differentiation has occurred and the gonad becomes a testis, it must migrate from its embryonic and fetal location near the caudal pole of the kidney into the scrotum to attain fertility. A mesenchymal structure, the gubernaculum testis, extends from the caudal pole of the testis through the inguinal canal to the genital tubercle and is responsible for guiding the testis into the scrotum. Shrinkage of the gubernaculum testis pulls the testis into the scrotum.

At the time of birth, the testes are usually within the abdomen, midway between the kidney and the inguinal ring (Baumans et al, 1981). Within 10 days, the testes move through the inguinal canal, and by 10 to 14 days of age, the testes are in the scrotum. Marked variability occurs in the time of descent of the testis into the scrotum, and scrotal positioning of the testis may not occur until 6 to 8 weeks of age. The inguinal rings of most dogs are closed by 6 months of age, precluding movement of testes from the abdomen to the inguinal canal if that has not already occurred (Johnston et al, 2001). Palpation of the testes in early life may be difficult because of small testicular size, small size of the neonate, poor scrotal development, variable amounts of scrotal fat, and involuntary withdrawal of the testes into the inguinal area. However, by 8 weeks of age, the testes should be palpable within the scrotum. Until 10 weeks of age, the testes of a few males may be periodically withdrawn into the inguinal region lateral to the penis following contracture of the cremaster muscle. These testes should move easily back into the scrotum with gentle digital pressure. The use of firm traction or failure to move the testicle into the scrotum should be viewed as a form of cryptorchidism.

DEFINITION.

Cryptorchidism refers to failure of one or both testes to descend into the scrotum by 8 weeks of age. An underdeveloped or aberrant outgrowth of the gubernaculum and failure of the gubernaculum to regress and pull the testis into the scrotum results in cryptorchidism (Wensing, 1980). The most common location for the undescended testis is the abdomen, although it may also be present in the inguinal canal or lateral to the penis (Fig. 29-1). Failure of normal testicular descent may involve both testes (bilateral) or only one testis (unilateral), in which case the right testis is more commonly involved (Cox, 1986). Bilateral cryptorchidism can be associated with male pseudohermaphroditism and other intersex states (see page 893).

INCIDENCE AND GENETICS.

Cryptorchidism is a common developmental defect. The incidence of cryptorchidism in the dog has been reported to range from 0.8% to 15% (Romagnoli, 1991; Ruble and Hird, 1993). Although nongenetic factors may be involved (e.g., relative size of testicle and the inguinal canal), genetics undoubtedly plays an important role in the development of cryptorchidism. The prevalence of cryptorchidism is higher in purebred dogs, in certain breeds of dogs (Table 29-1), and within certain families of a breed. Currently, cryptorchidism is believed to be a sex-limited autosomal recessive trait involving either a single gene locus or two gene loci. For the latter, one gene is believed to control internal testicular descent and organization of the epididymis and ductus deferens, and another gene controls external testicular descent.

TABLE 29-1 BREEDS OF DOGS AT HIGH AND LOW RISK FOR DEVELOPMENT OF CRYPTORCHIDISM

| Increased Risk | Decreased Risk |

|---|---|

| Toy Poodle | Beagle |

| Pomeranian | Cocker Spaniel |

| Yorkshire Terrier | English Setter |

| Miniature Dachshund | Golden Retriever |

| Cairn Terrier | Great Dane |

| Chihuahua | Labrador Retriever |

| Maltese | Saint Bernard |

| Boxer | Mongrels |

| Pekinese | |

| English Bulldog | |

| Old English Sheepdog | |

| Miniature Poodle | |

| Miniature Schnauzer | |

| Shetland Sheepdog | |

| Siberian Husky | |

| Standard Poodle |

Data from Hayes HM, et al (1985), Hoskins and Taboada (1992) and Johnston SD, et al (2001).

DIAGNOSIS.

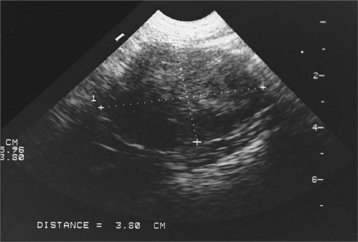

The diagnosis of cryptorchidism is usually made on routine physical examination with the finding of only one or no scrotal testes. Occasionally, the veterinarian examines a dog obtained as an adult without scrotal testicles. Careful inspection of the scrotal and antepubic area for surgical scars may reveal evidence of previous surgery. Because retained testes are capable of steroidogenesis, digital palpation of the prostate gland may provide evidence for the presence or absence of circulating testosterone. The prostate gland in castrated dogs will be small on digital palpation, compared with the prostate gland in bilaterally cryptorchid dogs (Johnston et al, 2001). Sometimes a scar cannot be visualized, or the question of whether one retained testis is present still needs to be answered. Careful palpation and a thorough ultrasound examination of the abdomen and inguinal region usually identify a cryptorchid testicle. Abdominal radiography is usually ineffective because of the small size of the testicle and the inability to differentiate it from other soft tissue structures. If palpation and ultrasonography are inconclusive, a baseline plasma testosterone determination may distinguish dogs without testes from those with one or two retained testes (see Table 27-7). In our laboratory, castrated adult males typically have a random baseline plasma testosterone concentration of less than 20 pg/ml; those with only cryptorchid testes have a concentration of 100 to 2000 pg/ml (0.1 to 2 ng/ml); and adult males with one or two scrotal testes have plasma testosterone concentrations of 1 to 5 ng/ml. No difference in baseline plasma testosterone concentration is found in normal males and those with unilateral cryptorchidism (one retained and one scrotal testes), regardless of the location of the cryptorchid testis (Mattheeuws and Comhaire, 1989).

Monorchidism (only one testis) and anorchidism (no testes) are possible differential diagnoses but are extremely rare in dogs (Verstegen, 1998). For this reason, all cases of absence of one or both testes should be considered cryptorchidism until proved otherwise.

TREATMENT.

Potential complications with cryptorchid testes include testicular torsion (see page 970), an increased incidence of testicular neoplasia (see page 964), male feminizing syndrome (see page 967), and blood dyscrasias. For these reasons, as well as the genetic implications, owners should be encouraged to have cryptorchid testes surgically removed once the dog has reached adulthood.

Testicular Hypoplasia

Testicular hypoplasia is a congenital, possibly hereditary disorder resulting from a lack of or marked reduction in the number of spermatogonia in the gonads. Testicular hypoplasia may result from inadequate primitive germ cell development in the yolk sac, failure of germ cells to migrate to the undifferentiated gonad, lack of an ability for these cells to multiply in the gonad, or early destruction of the cells during fetal development. Testicular hypoplasia may also be a component of some intersex states (see page 893). Because 50% to 70% of the volume of the testis is derived from the seminiferous tubules, a lack of germinal epithelial cells is associated with decreased testicular size. Testicular hypoplasia may be unilateral or bilateral. It is usually first noticed soon after puberty, which differentiates this condition from acquired testicular degeneration in the adult male (see page 974).

Aplasia of the Duct System

Failure of any part of the testicular duct system to develop results in impaired transportation of spermatozoa to the urethra, accumulation of sperm proximal to the obstruction, and possibly development of sperm granuloma and testicular degeneration (see pages 974 and 975). Although studies have not been done in the dog, aplasia of the duct system has been shown to be inherited in the bull, boar, and mink. Segmental aplasia is often unilateral, involving only one testis. Dogs with unilateral aplasia remain fertile, and the disorder is usually undiagnosed. If segmental aplasia is bilateral, the breeding dog is brought to the veterinarian with the primary complaint of infertility. Semen evaluation reveals azoospermia if bilateral aplasia is present. Seminal alkaline phosphatase concentration may be normal or decreased, depending on the site of aplasia (see page 940).

ACQUIRED DISORDERS

Testicular Tumors

TYPES.

Sertoli cell tumor.

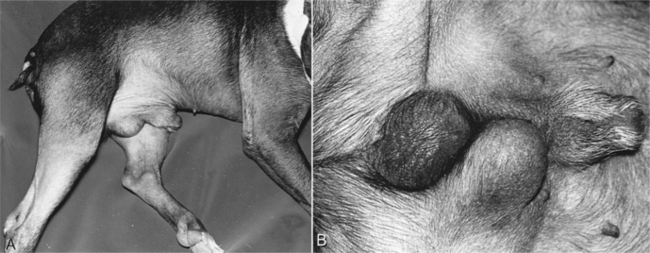

Sertoli cell tumors are derived from the Sertoli (nurse) cells of the seminiferous tubules. Sertoli cell tumors are usually slow-growing and noninvasive and typically range from 0.1 to 5 cm in diameter. Sertoli cell tumors may become quite large (i.e., 10 cm in diameter) when an intra-abdominal cryptorchid testis is involved (Fig. 29-2). These tumors feel firm and nodular on palpation. Approximately 10% to 20% are malignant, with metastasis occurring to the inguinal, iliac, and sublumbar lymph nodes and to the lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, and pancreas (Crow, 1980). The male feminizing syndrome is most commonly caused by Sertoli cell tumors (see page 967).

Seminoma.

Seminomas are derived from the spermatogenic cells of the seminiferous tubules and range in size from less than 1 cm to 10 cm in diameter. They feel soft on palpation. Seminomas are usually benign, although approximately 5% to 10% of seminomas are malignant (DeVico et al, 1994). Predisposing sites for metastasis are similar to those of malignant Sertoli cell tumors. Androgen secretion may be more common and male feminizing syndrome less common with seminoma versus Sertoli cell tumor.

Interstitial cell tumors.

Interstitial cell tumors are derived from the Leydig cells. These tumors are usually small (0.1 to 2 cm in diameter), nonpalpable, discrete masses that are hormonally silent and most commonly identified as an incidental finding at necropsy (Crow, 1980). Only 25% of dogs with interstitial cell tumors evaluated in one study had enlargement of the testes as a result of the tumor. In the remaining 75%, the tumor was not detectable. Interstitial cell tumors are almost always benign, and they feel soft and nodular on palpation. Paraneoplastic syndromes are uncommon with interstitial cell tumors and result from hyperestrogenism or hyperandrogenism (Medleau, 1989; Suess et al, 1992).

INCIDENCE.

Although individual reports of incidence vary, a review of the literature suggests an overall incidence of 44% for Sertoli cell tumor, 31% for seminoma, and 25% for interstitial cell tumor (Johnston et al, 2001). As many as 35% of dogs with testicular neoplasia have two or all three tumor types present at one time. The mean age for development of testicular tumors is 10 years, with a range of 3 to 19 years. The age of onset is earlier when the involved testis is extrascrotal. Certain breeds appear to be at increased risk for development of testicular neoplasia (Table 29-2).

TABLE 29-2 BREEDS OF DOGS AT HIGH AND LOW RISK FOR DEVELOPMENT OF TESTICULAR NEOPLASIA

| Increased Risk | Decreased Risk |

|---|---|

| Boxer | Beagle |

| Chihuahua | Labrador Retriever |

| German Shepherd Dog | Mongrels |

| Pomeranian | |

| Miniature Poodle | |

| Standard Poodle | |

| Miniature Schnauzer | |

| Shetland Sheepdog | |

| Siberian Husky | |

| Yorkshire Terrier |

The incidence of testicular neoplasia is much greater in cryptorchid testes than in normally descended testes—approximately 10 times greater (Hayes et al, 1985). Because the right testis is more commonly cryptorchid, it has a higher frequency of neoplastic involvement. Sertoli cell tumor accounts for approximately 60% and seminoma for 40% of tumors in cryptorchid testes. The incidence of these tumors is greater in inguinal than in intra-abdominal testes. Interstitial cell tumors are almost always found in descended testicles. Differences in incidence of tumor type based on location of testis may be due to differences in parenchymal temperature when the testis is located in the abdomen versus the inguinal region and the effect of temperature on viability of spermatogonia, Sertoli cells, and Leydig cells (Wallace and Cox, 1980). Scrotally located testes are at the proper temperature to ensure viability and function of all three cell types, thereby accounting for the approximately equal incidence of all three tumor types in scrotal testes.

CLINICAL SIGNS.

Clinical signs are variable and depend on the hormonal activity of the tumor. In general, clinical signs are caused by the space-occupying effect of the tumor itself or by its secretion of estrogens or androgens. Depending on the size of the tumor and the location of the involved testis, owners may bring their dog to the veterinarian with a complaint of scrotal or testicular enlargement, asymmetry in testicular size (Fig. 29-3), distended abdomen, or signs suggestive of a testicular torsion (see page 970). Rarely, stud dogs may be brought to a veterinarian for infertility. Infertility could result from pressure necrosis of normal testicular tissue by the tumor, a secondary immune-mediated reaction directed against spermatogonia following neoplasia-induced disruption of the blood-testis barrier, or hormonally induced testicular atrophy following secretion of estrogens or androgens by the neoplastic tissue. Peters et al (2000) documented a significant reduction in spermatogenesis in dogs with testicular tumors. Grootenhuis et al (1990) reported that secretory products from Sertoli cell tumors in cryptorchid dogs suppressed pituitary gonadotropin secretion and decreased responsiveness of the pituitary gland to exogenously administered GnRH. Estrogen-secreting testicular tumors may cause the male feminizing syndrome (see page 967), whereas androgen secreting tumors may cause prostatic dysfunction.

ANDROGEN SECRETION AND ITS EFFECT ON THE PROSTATE.

Pathologic changes of the prostate gland that have been associated with testicular tumors include cysts, hyperplasia, abscesses, squamous metaplasia, inflammation, and atrophy. Clinical signs supportive of prostatic disease include blood dripping from the penis, dysuria, hematuria, constipation, rear limb weakness or gait abnormalities, and systemic signs of illness (i.e., fever, inappetence, weight loss, abdominal pain; see Chapter 30). In addition to prostatic disease, perianal adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and perineal hernias are associated with androgen-secreting testicular tumors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree