Chapter 17 Disorders of the Reproductive and Urinary Systems

Disorders of the Reproductive System

Rabbit does are prolific breeders. They reach sexual maturity by 4 to 6 months of age, are induced ovulators, and have serial cycles that last 7 to 14 days until conception. A mildly swollen and congested vulva often accompanies receptivity and should not be mistaken for a vulvitis or vaginitis. Bucks are precocious and may attempt to breed as early as 3½ to 4 months of age. Spraying is a normal sexual behavior of intact bucks and sometimes of does and should not be confused with inappropriate elimination because of urinary tract infection or inflammation. In an evaluation of wild European hares (Lepus europaeus), reproductive abnormalities were found in 20.8% (51 of 245) of the does examined. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia was relatively common and often accompanied by hydrosalpinx. Extrauterine fetuses, neoplasms, pseudopregnancies, and resorptions also were also found. However, although pseudopregnancies and resorptions were found in young adults (<12 months) as well as older hares, conditions possibly causing infertility were almost always seen in older hares, with prevalences up to 46.2%. Only hares with access to known sources of estrogens (mixed pastures including legumes known to produce phytoestrogens and mycoestrogens) exhibited pathologic conditions, but sympatric European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) did not, which is consistent with known difference in responses between the corpora lutea of the two species to exogenous estrogen. Cystic ovarian tumors seem to be relatively common in hares, and tumors of the mammary gland and uterus have also been reported.76 Disorders of the reproductive tract in female pet rabbits are seen less commonly because educated owners typically elect to have their rabbits spayed to prevent uterine disease. In the second edition of this text, it was reported that less than 6% of all rabbits presented to the University of Wisconsin Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital were diagnosed with reproductive disorders.62 A review of the data from the University of California-Davis Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital reported a 4% incidence of uterine disorders (not including healthy rabbit ovariohysterectomies) from January 1999 through January 2009 in presenting rabbits (JPM). However, older intact females must be carefully and regularly monitored for reproductive tract disease, especially neoplasia. Careful abdominal palpation allows for the detection of ovarian or uterine enlargement. Any perceived abnormality should be investigated fully and aggressively.

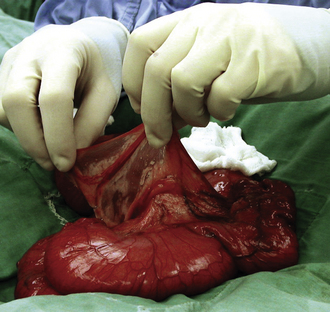

Uterine Adenocarcinoma

Uterine adenocarcinoma is the most common neoplasia of female rabbits.85 Age is the most important factor in its development and occurrence is independent of breeding history. Rabbits of certain breeds (tan, French silver, Havana, and Dutch) that are more than 4 years old have an incidence of 50% to 80%.4,37,85 With age, the endometrium undergoes progressive changes, a decrease in cellularity, and an increase in collagen content. These changes are associated with the development of uterine cancer.4 Adenocarcinoma of the uterus is a slowly developing tumor. Local invasion of the myometrium occurs early and may extend through the uterine wall to adjacent structures in the peritoneal cavity; hematogenous metastasis to the lungs, liver, brain, and bones may occur within 1 to 2 years.85 Early clinical signs, such as decreased fertility, small litter size, and an increased incidence of fetal retention, fetal resorption, and stillbirths may be recognized in a breeding doe. The first signs observed in many pet rabbits are hematuria or a serosanguineous vaginal discharge. Frank blood in the urine is most pronounced at the end of urination. Cystic mammary glands can develop concurrently with uterine hyperplasia or adenocarcinoma.32,45 Clinical signs of late-stage adenocarcinoma include depression, anorexia, and dyspnea if pulmonary metastasis has occurred. Ascites may be present. The diagnosis relies on palpation of an enlarged uterus, uterine nodular masses (1-5 cm in diameter), or both in the caudal abdomen. Adenocarcinomas are often multicentric, involving both uterine horns (Fig. 17-1).4,85 Other causes of uterine enlargement include pregnancy, pyometra, metritis, hydrometra or mucometra, endometrial venous aneurysms, endometrial hyperplasia, and other tumors such as leiomyosarcoma. In one pet rabbit, both a leiomyoma and an adenocarcinoma of the endometrium were found, with the latter extending into the leiomyoma.48

The expression of estrogen receptor-alpha and progesterone receptor in normal, hyperplastic, and neoplastic endometrium in rabbits was evaluated by immunohistochemistry. Sixteen of 27 cases of normal uteri (59.3%) and 13 out of 19 hyperplasias (68.4%) stained positive with both receptor types. Adenocarcinomas were further subdivided into 26 papillary and 16 tubular/solid adenocarcinomas. Papillary adenocarcinoma infiltrated the myometrium late in the disease and caused attenuation of the myometrium. In contrast, tubular/solid adenocarcinoma invaded the deep myometrium early in the disease without thinning of the myometrium. Twenty-one out of 26 (80.8%) cases of papillary adenocarcinoma were receptor negative for both types, whereas 15 out of 16 (93.8%) of the tubular/solid adenocarcinomas were positive for one or both, suggesting that there may be two different developmental pathways for uterine adenocarcinomas in the rabbit.2

Other reported uterine neoplasias in rabbits include spontaneous choriocarcinoma and a homologous malignant mixed müllerian tumor.29,43

Endometrial Hyperplasia or Uterine Polyps

Endometrial changes may occur along a continuum—from polyp formation, to cystic hyperplasia, to adenomatous hyperplasia, to adenocarcinoma—as it does in humans.20,37,45 Uterine hyperplasia is associated with aging, as are cystic and hyperplastic changes in endometrial glands. Other reports, however, have found no association between cystic hyperplasia and uterine adenocarcinoma in rabbits because adenocarcinomas are associated with senile atrophy of the endometrium.4 Cystic endometrial hyperplasia is the major indication of phytoestrogenism in sheep. Hares are particularly sensitive to the luteotrophic effect of exogenous estrogen, which can double the length of pseudopregnancy in that species; however this did not seem to be the case in sympatric rabbits.75

Clinical signs of endometrial hyperplasia can mimic those associated with uterine adenocarcinoma, including intermittent hematuria, anemia, and a decrease in activity. A firm, irregular uterus can sometimes be detected by palpation. Cystic mammary glands and cystic ovaries can occur concurrently with this condition.32,45 Ultrasonography is the most efficient diagnostic tool to image soft tissue changes in the uterus although other imaging modalities can provide the diagnosis of uterine changes. Ovariohysterectomy is the recommended treatment, and a thorough exploration of the abdomen is warranted.

Pyometra and Endometritis

The main reasons for culling adult rabbit does on two Spanish rabbit farms over 1 year included pyometra (8.7%). Pasteurella species were more prevalent, although two strains of Staphylococcus aureus were identified by using polymorphism of the coagulase gene as the criterion. One of these strains was responsible for the majority of the staphylococcal infections and was isolated from several pathological processes.72 S. aureus was found to be a cause in another study.81

Diagnosis relies on palpation of a doughy, enlarged uterus, best demonstrated on radiographs or ultrasound. If the uterus is greatly enlarged, use caution in palpating the abdomen, because the uterine wall becomes very thin and may be friable. Ultrasound is advantageous because it can often rule out other uterine conditions such as polyps, masses, or cystic changes. Results of a complete blood count (CBC) may be normal or may show a slight leukocytosis due to a heterophilia. Evaluate serum or plasma biochemical values, because chronic inflammation of the uterus has been reported to induce amyloid deposition in the kidneys.35 Cytologic assessment and a Gram’s stain of cervical mucus or drainage can assist diagnosis.

Pasteurella multocida and S. aureus are frequently isolated from rabbits with pyometra or metritis. Venereal transmission occurs when infected does breed with uninfected bucks, or vice versa. P. multocida can localize in the genital tract by hematogenous spread from another location, or a retrograde infection can occur as a result of vaginitis.17 Ovarian abscesses may occur concurrently with P. multocida pyometra.39 Rare cases of naturally occurring metritis or pyometra have been associated with Chlamydia species, Listeria monocytogenes, S. aureus, Moraxella bovis, Actinomyces pyogenes, Brucella melitensis, and Salmonella species.34,59,74,84 Postpartum metritis can occur in conjunction with hypervitaminosis A; the delivery of stillborn young and metritis have been associated with uterine torsion.34 For a breeding rabbit with mild endometritis, appropriate antibiotic treatment, the administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and fluid therapy may be sufficient, but the tenacious and caseous nature of inflammatory exudates in rabbits makes it impossible to achieve adequate drainage of the uterus. The use of prostaglandins to assist uterine contraction and drainage has not been reported. Ovariohysterectomy is the best choice for the treatment of pyometra.

Pregnancy Toxemia

Pregnancy toxemia usually occurs during the last week of gestation, when nest-building behavior begins. Rabbit fetuses show considerable development during the second half of pregnancy.23 The exact causes leading to metabolic disturbances and pregnancy toxemia are unknown. It is more common in obese rabbits. Inadequate caloric intake predisposes pregnant rabbits to toxemia, and environmental changes or stress can precipitate the disease. Hair pulling for nesting can contribute to hairball formation and inappetence.63 Weakness, depression, incoordination, anorexia, abortion, convulsions, and coma are common clinical signs. Signs can progress over 1 to 5 days, or death may occur acutely. Some rabbits are dyspneic and may have ketotic breath. The urine becomes acidic and clear because the lower pH decreases the concentration of calcium carbonate crystals. Clinical pathology findings include acidic urine (pH 5-6), proteinuria, ketonuria, hyperkalemia, ketonemia. hyperphosphatemia, and hypocalcemia. Hepatic enzymes may be elevated and lipidosis is commonly noted at necropsy.

Pseudopregnancy

Pseudopregnancy (pseudocyesis, false pregnancy) can occur in rabbits, even in pet does kept singly. Pseudopregnancy typically lasts 16 to 17 days and may be followed by hair pulling and nesting behavior.64 The corpus luteum secretes progesterone, causing uterine and mammary development.60 Mammary development is most pronounced in the first 10 days of false pregnancy, after which mammary involution typically follows by day 16.60,64 The condition resolves spontaneously but may recur or may lead to hydrometra or pyometra. Pseudopregnancy strongly depresses fertility, and its cause is still unknown.79 A lower kindling rate was found in group-housed does with one buck versus those housed in a one-to-one ratio, with pseudopregnancies found in 23% of the does in the group-housing system against 0% in the control does housed individually.69 Ovariohysterectomy is the treatment of choice and ideally would be performed once the mammary tissue had involuted. Hormonal therapy with either progestins or androgens is of unproved effectiveness and should be considered only in rare cases where pseudopregnancy is protracted or refractory.

Abdominal Pregnancy

Abdominal pregnancy sometimes occurs in does and is usually subclinical.1,6,7,16 Extrauterine implantation of fertilized ova, often on the parietal peritoneum, can lead to the development of near-term fetuses, with subsequent mummification.7 It is classified as a primary abdominal pregnancy if there is no evidence of uterine rupture, with presumed regurgitation of early embryos from the uterine tube. The abdominal pregnancy is secondary if there is evidence of uterine rupture. A study of 550 adult fertile female New Zealand white rabbits culled from two rabbit farms in Valencia (Spain) found that 5% had abdominal pregnancies, with 25% of those having normal reproductive tracts.28 Mummified fetuses were found free in the abdominal cavity of a healthy doe presented for a routine examination.6 The uterus and ovaries appeared normal, and the rabbit made an uneventful recovery after surgical removal of the fetuses. False abdominal pregnancy refers to cases in which fetal implantation occurred in the uterus and fetuses were later expelled into the abdominal cavity as a result of a traumatic event.7 One report describes a rabbit mortality associated with three partially mummified, full-sized fetuses free in the abdominal cavity.1 On postmortem examination, one uterine horn showed evidence of a relatively recent tear. The doe had delivered three kits 3 weeks previously, suggesting that the uterine rupture had occurred at parturition. Primary abdominal pregnancy or false abdominal pregnancy should be considered on the differential when palpable fetuses are present in does that have not undergone timely parturition.28 New husbandry systems in rabbits, such as artificial insemination, are factors to be considered.28 Surgery is the treatment of choice for the individual animal to remove the fetuses, and ovariohysterectomy is indicated if the pregnancy is identified early enough. Euthanasia may be required in advanced cases of abdominal pregnancy.

Abortion and Resorption

Fetal death before 21 days of gestation typically resolves as resorption, whereas fetal death after 21 days results in abortion. A critical period in gravid does occurs at 21 days of gestation because of a temporary reduction in blood flow to the uterus and the changing size and shape of the fetuses. When abortion or fetal resorption is suspected, a thorough history is extremely important. Ask questions such as: “Is this the first litter? Is there a prior history of abortion? Have any medications been administered recently? Has there been a recent change in environment? Are any other does aborting?” Always check the doe for remaining fetuses by radiographs and/or ultrasound. Submit fetuses and placentas for anerobic and aerobic bacterial culture and histopathologic examination. Fetal resorption is not regarded as a disease condition in lagomorphs, since it occurs in response to social or environmental stress.76 Possible causes of fetal abortion are numerous and include infection, stress, genetic predisposition, trauma, drug use, and dietary imbalances (e.g., deficiencies of vitamin E, vitamin A, and protein). Listeria species have a predilection for the gravid uterus; this should be considered in rabbits with late-term abortion.84 A herpesvirus infection affecting mini Rex and crossbred meat rabbits was identified in a rabbitry in Alaska, with one of the symptoms being abortion.38

Reduced Fertility

One or more factors can contribute to reduction in fertility, including malnutrition (e.g., excess vitamin A, deficiencies of vitamins A, D, or E), heat stress, systemic illness, nitrate contamination of food or water, environmental disturbances, a decrease in daylight, endometrial carcinoma, metritis, or pyometra. Old age, sexual exhaustion, or breeding of rabbits that are too young are additional causes of infertility. Vitamin E deficiency causes myodystrophy, which can lead to abortions, stillbirths, and neonatal deaths. An increased level of creatine phosphokinase occurs with hypovitaminosis E and indicates a need for diet supplementation.59 Hypervitaminosis A can cause fetal resorptions, abortions, and stillbirths.18,75 A suppurative metritis may follow the delivery of dead fetuses.18 Hypovitaminosis A can cause similar reproductive disorders, resulting in poor fertility and weak, hydrocephalic young. The National Research Council recommends vitamin A levels of 1,160 IU/kg of diet for gestation, or approximately 20 mg/kg of body weight per day.57 Administration of vitamin E for 2 weeks lowered the serum vitamin A levels and increased the vitamin E serum and liver levels. It was concluded that vitamin E therapy appears to be an effective treatment for hypervitaminosis A.75

Prolapsed Vagina

A prolapsed vagina manifests itself as a blood-covered mass of swollen and fragile tissue protruding from the vulva. The prolapse may be full of clotted blood. Affected rabbits are depressed or recumbent with an increased respiratory rate or are in shock with cool extremities. Pale mucous membranes or cyanotic ears and mucous membranes indicate severe shock. The hematocrit in such rabbits may be as low as 9%.82 Treatment is directed at correcting hypovolemic shock and blood loss. Opioid analgesia is recommended and NSAIDs can help to reduce inflammation as well as providing analgesia. Reduce the prolapse under anesthesia or surgically amputate the tissue if it is necrotic. Prolapses start from the proximal circular part of the vaginal vault just distal to the urethral opening.82 Eight cases of vaginal prolapse were described in closely related rabbits during periods of increased sexual activity or receptivity, suggesting a genetic susceptibility.82

Endometrial Venous Aneurysms

Multiple endometrial venous aneurysms can cause hematuria because of episodic bleeding in the lumen of the uterus. Cylindrical blood clots molded within the uterine horns are typically passed with the urine and are highly suggestive of this condition. Affected does are at high risk for fatal exsanguination from uterine hemorrhage, and ovariohysterectomy should be performed as soon as the animal is stabilized. Endometrial venous aneurysms occur in young does of larger breeds. The condition was reported in three New Zealand white rabbits and was confirmed by exploratory laparotomy and histopathologic examination of the uterus.9 In rabbits with this condition, the uterine horns have multiple blood-filled endometrial varices (veins) that periodically rupture into the uterine lumen, causing the clinical hematuria. Although the causes have not been elucidated, venous aneurysms in other species are related to congenital defects of the adventitia, increased intraluminal pressure, or trauma.9

Hydrometra

Hydrometra is the accumulation of watery fluid in the uterus. It has been described in four unbred sandy half-lop rabbits from the same research colony55 and in New Zealand white rabbits.34 Clinical signs include an enlarged fluid-filled uterus, increased respiratory rate, anorexia, and weight loss. Transabdominal uterocentesis yields clear fluid with a low specific gravity, a low cell count, and a moderate amount of protein.34 Diagnosis can be supported by radiography and ultrasonography. The rabbits in the published reports were all euthanatized or found dead, and no anatomic abnormalities could be correlated with this condition.55 Ovariohysterectomy and supportive care are indicated if hydrometra is diagnosed in a pet rabbit.

Uterine Torsion

Torsion of the uterus is rare in rabbits but has been reported in association with pregnancy, hydrometra, and endometritis.34 Clinical signs of uterine torsion include shock, cachexia, and abdominal distention with hydrometra, or a bloody vaginal discharge when seen with endometritis.34 The cause of uterine torsion is difficult identify and the prognosis is grave. Following critical support, pain management, and stabilization of the doe, ovariohysterectomy is the treatment of choice.

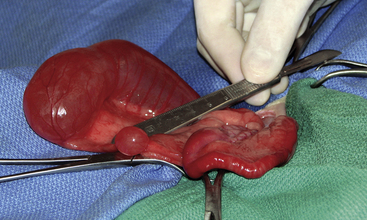

Uterus Unicornis and Uterine Atresia

Two cases of congenital anomalies seen in domestic rabbits have been described. Uterus unicornis was reported in a 4-year-old intact female Rex rabbit presenting with some urinary and behavioral issues involving two ovaries but only one uterine horn, cervix, and oviduct. There was no evidence of previous abdominal surgery. After a modified ovariohysterectomy, the rabbit recovered uneventfully. Uterine atresia was incidentally found in a 9-month-old intact female white New Zealand rabbit. The left portion of the uterus was normal but the right lacked a cervix and the caudal portion of the right uterus. A large and a second smaller cystic structure midway between the vagina and ovary in the mesometrium was noted (Fig. 17-2). The oviduct was traced to a normal-appearing right ovary. There have been anecdotal reports of uterus unicornis on the Veterinary Information Network (VIN, www.vin.com, accessed February 19, 2009) in other rabbits. The congenital etiology of uterine anomalies makes it important to assess the affected animal for renal and ureteral abnormalities.80

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree