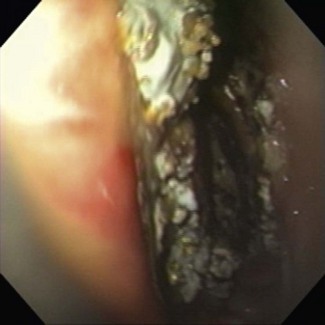

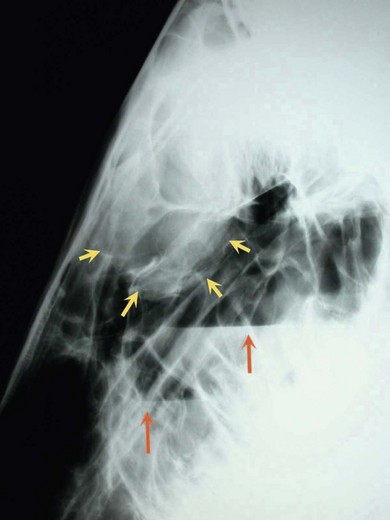

Chapter 5 5.1 Diseases of the external ear 5.2 Diseases of the middle ear 5.3 Diseases of the auditory tube diverticulum (ATD) (guttural pouches) 5.5 Diverticulitis of the guttural pouch 5.8 Disorders of the external nares 5.9 Diagnostic approach to nasal and paranasal sinus disease 5.10 Treatment of sinu-nasal disorders 5.11 Primary and secondary empyema 5.12 Progressive ethmoidal haematoma (PEH) 5.14 Mycotic rhinitis and sinusitis 5.15 Sinus and nasal neoplasia and polyps 5.16 Other sinu-nasal disorders 5.17 Idiopathic headshaking in horses 5.18 Diagnostic approach to conditions causing airway obstructions in horses Functional concepts of conducting airways Intra-narial larynx and role of the soft palate Clinical signs of obstructive dyspnoea Respiratory noises at exercise Treadmill and overground endoscopy of horses during exercise 5.19 Common upper respiratory tract obstructive disorders of horses 5.20 Recurrent laryngeal neuropathy (RLN) 5.21 Dorsal displacement of the soft palate (DDSP) 5.22 Epiglottal entrapment (EE) 5.25 Fourth branchial arch defects (4-BAD) 5.26 Axial deviation of the ary-epiglottal folds (ADAF) 5.27 Other causes of dynamic airway collapse 5.28 Other causes of airway obstruction in horses Pharyngeal lymphoid hyperplasia (PLH) Pharyngeal and laryngeal neoplasia Acquired tracheal obstructions 5.29 Miscellaneous throat conditions of horses Abnormal ear carriage may indicate aural pain or malfunction of the auricular muscles. A distant inspection may reveal abnormal carriage of the ear or of the head as a whole. Swellings or overt otorrhoea voided over the parotid area or a discharging sinus tract at the rostral margin of the pinna (see ‘Temporal teratoma’, below) may be seen. The discharge may be malodorous if secondary infection is present. Smears may be taken to identify parasitic mites under low-power microscopy. Young horses are invariably involved, i.e. under 1 year of age when signs first appear. There may or may not be a visible or palpable swelling. A form of papillomatosis with the formation of discrete white plaques on the underside of the pinnae is common. The aetiology of these plaques is not known, but some clinicians believe that they are the result of repeated insect harassment (see 13.7). Anatomy and function of the middle ear The middle ear comprises the space within the tympanic bulla and includes the ear drum, auditory ossicles and the tensor tympani and stapedius muscles. The internal auditory tube runs from the rostral wall of the middle ear to the nasopharynx and provides the means for pressure equilibration across the tympanic membrane and mucus clearance from an enclosed space. The middle portion of this tube passes through a diverticulum, the guttural pouch, which is considered separately (see 5.3). Adjacent to the middle ear lie the facial nerve as it emerges from the skull and the tympano-hyoid articulation. The outer wall of the tympanic bulla is visible during endoscopy of the guttural pouch. Endoscopy of the auditory tube diverticulum (ATD) (see 5.3) permits inspection of the ventral aspect of the tympanic bulla and of the internal os of the eustachian tube. THO comprises a proliferative osteitis of the petrous temporal and proximal stylohyoid bones. The aetiology of the underlying disorder is not known, and the presence of infection is rarely confirmed. A degenerative inflammatory process is most likely involved. Ankylosis of the joint between the stylo-hyoid and temporal bones is a common feature of THO. The consequences of this ankylosis include pathological fractures through the middle and inner ears causing peripheral vestibular signs (see Chapter 11) or through the stylo-hyoid the effect of which is to limit the horse’s ability to move the tongue. The first sign of temporo-hyoid osteitis may be facial palsy when the facial nerve is compressed by the expanding bony lesion as it passes through the dorsal recess of the lateral compartment of the ATD. The diagnosis can be confirmed by endoscopy of the ATD, and the consequences can be relieved by osteotomy of the keratohyoid, thus pre-empting the pathological fracture. Complete occlusion of an ATD can occur in cases of chronic empyema or chondroid formation. Long-term catheterization may lead to weakening of the ostium and erosion of the cartilage flap. 1. Hyovertebrotomy. An incision is made parallel and immediately cranial to the wing of the atlas. The parotid salivary gland is reflected forwards. An endoscope introduced into the ATD per nasum serves to illuminate the membranous lining deep in the surgical site once the loose connective tissue has been bluntly separated. When this approach is used the ATD is entered through the lateral wall of the medial compartment where it projects caudal to the stylohyoid bone. 2. Viborg’s Triangle. Access to the ATDs by this approach is very restricted except in conditions where there has been stretching of the tissues through distension of the pouch which in turn increases the overall size of Viborg’s triangle. 3. Paralaryngeal (Whitehouse) approach. With the horse in dorsal recumbency, a ventral midline incision is made over the larynx. The dissection passes lateral to the larynx, trachea and cricopharyngeal muscle to reach the pouches ventro-medially. Entry to the ATD is again made medial to the stylohyoid bone. The depth of incision limits the value of this approach. 4. Modified Whitehouse approach. The site of the incision corresponds to that used for prosthetic laryngoplasty, i.e. it lies ventral to the linguo-facial vein and then follows the same route to enter the pouch. This approach may be used in the standing sedated patient for the removal of chondroids when the horse is considered a poor risk for general anaesthesia. Aetiology: In this condition the ATD ostium acts as a non-return valve so that air can enter the pouch but cannot escape. Clinical signs and diagnosis: This is a condition of foals which usually manifests itself within a few days of birth and it is thought to arise from a congenital malfunction of pharyngeal opening of the pouch rather than a physical obstruction. Dysphagia and dyspnoea may be exhibited by virtue of the size of the distension. Occasionally ATD tympany is an acquired disorder of the adult horse. Treatment: Three principles have been applied for the relief of ATD tympany: 1. Dilation of the pharyngeal ostium on the affected side. 2. The creation of a fistula between the normal and distended pouches by the removal of a section of the medial septum. 3. Blunt fistulation between the ATD and the pharyngeal recess. Aetiopathogenesis: These are poorly defined and poorly understood conditions in which inflammation of the mucous membrane lining of the ATDs occurs and which can loosely be termed ‘diverticulitis’. They include strangles infection in the lymphoid tissue of the walls of the pouches, empyema, chondroid formation and chronic diverticulitis. • The clinical signs of empyema include a bilateral purulent nasal discharge and swelling of the parotid region. • The distension of the affected pouch into the pharynx may produce obstructive dyspnoea. The nasal discharge is sometimes malodorous. • Lateral radiographs confirm the loss of air contrast from within the ATD, and if the pus is still fluid, an air/fluid interface will be demonstrable. • An indwelling self-retaining Foley balloon catheter may be used for drainage of the ATD and for long term irrigation in the management of chronic cases. • Inspissated caseous pus/chondroids may be liquefied by a process of repeated lavage via the pharyngeal ostium aided by the instillation of acetylcysteine. • Chondroids which do not respond to conservative management may be removed individually using trans-endoscopic grasping forceps if they are small in number; otherwise surgical removal is required to extirpate chondroids. • Whenever chondroids are bilateral the ventral Whitehouse approach is preferred so that both pouches can be entered through the same incision. Aetiopathogenesis: The fungal plaques of guttural pouch mycosis (GPM) are usually found in one of two characteristic sites: • The development of an invasive fungal plaque on the mucosal wall of the ATD of a horse will produce consequences ranging from nil to fatal. • Spontaneous epistaxis at rest is the most frequent sign noted by owners and usually consists of a small quantity of fresh blood at one nostril in the first instance. • A number of further minor haemorrhages may follow but, if untreated, exsanguination is a probable final outcome. • It is unusual for the first episode of epistaxis to be fatal, but the course of the disease from first to final haemorrhage rarely spans more than three weeks and is more likely to be a matter of days. Endoscopic evidence of pharyngeal paralysis includes persistent dorsal displacement of the palatal arch, the presence of saliva and ingesta in the nasopharynx, weak pharyngeal contractions and a failure of one or both of the pharyngeal ostia of the ATDs to dilate during deglutition (see Figure 1.2). Diagnosis: The clinical signs are not specific, but whenever a horse is presented with spontaneous epistaxis the possibility of GPM should be explored because delayed treatment may result in a fatal outcome. A definitive endoscopic diagnosis of a mycotic plaque in the ATD (Figure 5.1) is not always straightforward; two caveats should be heeded: • First, the stress of handling the horse may precipitate a fatal epistaxis. • Second, endoscopic visibility within the affected pouch may be poor after a recent haemorrhage, and accurate location of the lesion will not be possible. • Medical treatment of GPM, be it by the use of topical or systemically administered antimycotic drugs or by a combination of both, is likely to be unsuccessful. • Surgical occlusion of the branches of the carotid artery is recommended. • The treatment of choice is transarterial coil embolization. • The internal carotid is not an end-artery and therefore the placement of a simple ligature on the cardiac side of the lesion will not always be successful because retrograde haemorrhage may occur. • Occlusion of the distal segment with a balloon-tipped catheter combined with proximal ligation of the ICA is superior. • Topical antimycotic medication as an adjunct to arterial occlusion is probably not necessary. Prognosis: Those cases of GPM not showing neurological complications can usually be brought to a successful conclusion by arterial occlusion surgery. Although a small proportion of horses showing pharyngeal paralysis recover normal swallowing function, destruction on humane grounds is a more likely outcome and is indicated as soon as the patient shows signs of dehydration or aspiration pneumonia. Laryngeal hemiplegia resulting from GPM can be managed as for the idiopathic form recurrent laryngeal neuropathy (see ‘Treatment’ in 5.20). • A congenital deformity of the nose resulting from gross foreshortening of the premaxilla on one side. • The deformity is not thought to be genetically transmitted but may be due to abnormal positioning in utero. • The deformity is externally obvious. • Even radical surgery is unlikely to render the horse suitable for exercise. • Deviation of the nasal septum is usually accompanied by a degree of wry nose which may be very subtle on occasion and is most easily recognized through incisor malocclusion. • It is normal for the alar folds which form the floor of the false nostril sometimes to vibrate during exhalation. This is the origin of the vibrant expiratory noise known as ‘high blowing’. Occasional horses exhibit a comparable vibrant sound during inspiration. • Confirmation that the origin of the noise lies at the alar folds is achieved by placing full thickness mattress sutures from the skin at the dorsal aspect of the nose across the openings of the false nostrils. The technique is performed under local anaesthesia so that the noise can be compared before and after suture placement. A positive result is an indication for resection of the alar folds. • Epidermal inclusion cysts (sebacious cysts) occasionally develop in the lining of the false nostril. • These are painless and can be seen at the dorsal aspect of the nose rostral to the naso-maxillary notch. • Although the swellings can be sizeable they do not obstruct respiration and are of cosmetic significance only. • Chemical ablation of the lining by flushing with 10% formalin solution after evacuation of the contents is usually effective. The formalin is left in situ for 5 minutes before being flushed clear with sterile saline solution. • Otherwise removal by careful dissection from the dorsal skin surface is straightforward, and recurrence is improbable. • Wounds to the nostrils are typically sustained when a horse pulls backwards having caught the margin of its nose on a hook. • These injuries demand meticulous management in the acute stage with layer-by-layer anatomical restoration. • Inadequately managed nostril tears lead to stricture of the nostril aperture and a major reduction in athletic capacity. The five paired paranasal sinuses of the horse are: • The apices of the 4th, 5th and 6th cheek teeth (109, 110, 111, 209, 210 and 211) lie within the maxillary sinuses; they are most prominent in young horses and recede towards the floor of the sinuses with age. • The roots of the 3rd cheek tooth (108 and 208) form the rostral wall of the RMS. • When dental periapical suppuration is the cause of sinusitis and oral extraction is unsuccessful, surgical exodontia requires that the roots are approached through the sinuses. • Structures such as the nasolacrimal canal, infra-orbital canal, vein and artery of the angle of the eye are vulnerable to iatrogenic insult. • The clinical signs of paranasal sinus diseases almost invariably include a nasal discharge, which may be mucoid, purulent, haemorrhagic or a combination of these. • There may also be facial swelling and obstructive dyspnoea. • Some expansive lesions in this area displace orbital tissues resulting in exophthalmos, but it is exceptional for a sinus disorder to extend caudally into the cranium to provoke central nervous signs. • The intranasal structures are richly vascular, and it is not surprising that trauma and destructive conditions frequently lead to epistaxis. • Note should be made of possible contact with infectious respiratory disease and of the duration and nature of any nasal discharge. • It is unusual for sinusitis to be bilateral, and it is logical that the discharge will be largely unilateral when its origin lies proximal to the caudal limit of the midline septum. • When a horse is presented with unilateral epistaxis enquiries should be made regarding associations with exercise to eliminate a diagnosis of exercise-induced pulmonary haemorrhage (see 6.7). • Epistaxis due to guttural pouch mycosis may be acute, and, even if episodic, the course of the history is unlikely to exceed 3 weeks (see 5.6). • A diagnosis of progressive ethmoidal haematoma (PEH) is more likely to be correct when episodes of epistaxis span a longer period, especially if the blood is not fresh. • A foetid nasal discharge points to suppuration, but this could arise from a wide range of chronic sinus lesions. • The facial area should be inspected for evidence of deformity of the supporting bones through swelling or trauma. • Subcutaneous emphysema may be detected after trauma in some cases where the sinus walls have been disrupted. • Percussion of the walls of the paranasal sinuses is an unreliable technique, but increased resonance may be perceived when the walls become thin, or dullness may develop when the sinuses are completely filled by fluid or soft tissue. • The airflow at each nostril should be checked to assess obstruction of the nasal meati. • The clinical crowns of the cheek teeth are examined for the presence of fracture, displacement or impaction of degenerate ingesta. • The patency of the nasolacrimal duct can be checked by catheterisation and infusion of saline solution from either end. Endoscopy of the nasal area is performed in two ways: • First, by conventional passage of the instrument into the nasal meati. • Second, by direct inspection of the sinus contents through small trephine holes. 1. Nasal meati – are they narrowed? Compare with contralateral side. 2. Is narrowing of the meati the result of conchal distension? 3. Is narrowing due to a soft-tissue mass? Does the colour of the mass indicate a PEH, cyst or tumour? Can a mass be seen extending caudal to the midline septum when the endoscope is passed via the opposite nostril? 4. Sinu-nasal drainage ostium in caudal middle meatus: 8. Direct sinus endoscopy, check for: The good contrast provided between bone and air renders the nasal chambers and paranasal sinuses excellent candidates for radiographic diagnosis (Figure 5.2). Erect lateral, lateral oblique, lesion-oriented oblique and ventro-dorsal views may be required for a comprehensive investigation. The radiographic signs of sinu-nasal disease include: The complex anatomy of the equine head, with the frequent superimposition of normal and abnormal structures, renders the interpretation of radiographs difficult. CT scanning offers a precise means to locate abnormalities (Figure 5.3). • Accurate diagnosis of the primary sinu-nasal disorder and removal of diseased tissue. • Restoration of the normal drainage mechanisms or the creation of alternative drainage through a sinu-nasal fistula. • Adequate visibility within the sinuses and nasal meati for accurate diagnosis and surgery. • Means to control haemorrhage during surgery and in the recovery period. • A safe airway during surgery and recovery. • Facilities for topical post-operative treatments and for monitoring progress. • An early return to exercise. • Simple trephination also aims to restore normal sinus drainage but with the addition of irrigation and topical antibiotic infusion to clear stagnant mucus and eliminate secondary infection. • Trephination is performed using local anaesthetic infiltration with the horse standing. • The preferred site for trephination is into the CMS in the angle formed between the margin of the bony orbit and the facial crest. • In-dwelling balloon catheters provide a good means for regular irrigation over a number of days until the discharge to the nostril ceases. • The RMS is less available for simple trephination especially in young horses where the lateral compartment is largely occupied by the roots and reserve crowns of the third and fourth cheek teeth. • The bulla of the RMS may bulge caudally into the CMS when it is inflated by pus, and this is easily punctured and excised. • This form of fistulation may be performed through a trephine hole into the CFS before introducing tubing for subsequent irrigation and drainage. • In surgical practice the fistulae described provide convenient routes by which to lead sock-and-bandage pressure packs to the nostrils (see below). • Fronto-nasal or maxillary flap surgery is required for extensive excisional procedures such as the removal of sinus cysts, PEHs and selected tumours as well as for the relief of chronic sinusitis and fistulation techniques. • Radical exposure of the nasal chambers, paranasal sinuses and their contents can be achieved through the bony walls of the supporting bones.

Disorders of the ear, nose and throat

5.1 Diseases of the external ear

Clinical signs of otitis externa

Investigation of ear disorders

Temporal teratoma

Chronic keratinization plaques

5.2 Diseases of the middle ear

Otitis media

Temporohyoid osteoarthropathy (THO)

5.3 Diseases of the auditory tube diverticulum (ATD) (guttural pouches)

Radiographic examination of ATDs

Topical treatment of ATDs

Surgical approaches to ATD

5.4 Guttural pouch tympany

5.5 Diverticulitis of the guttural pouch

Chronic ATD empyema and chondroids

5.6 Guttural pouch mycosis

5.7 Other ATD disorders

5.8 Disorders of the external nares

‘Wry nose’

Hypertrophy of alar folds

‘Atheroma’ of false nostril

Trauma

5.9 Diagnostic approach to nasal and paranasal sinus disease

Common presenting signs

History

Physical examination

Endoscopy

Radiography

Other imaging modalities

5.10 Treatment for sinu-nasal disorders

Trephination

Facial flap surgery

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Disorders of the ear, nose and throat