Chapter 8 8.1 Evaluation of the urinary system 8.3 Acute renal failure due to renal disease 8.4 Chronic renal failure (CRF) 8.8 Patent and persistent urachus 8.10 Polyuria/polydypsia (PUIPD) 8.11 Diagnosis of diseases of the testis and associated structures 8.15 Inguinal herniation and rupture 8.16 Torsion of the spermatic cord 8.19 Diagnosis of diseases of the penis and prepuce 8.20 Penile and preputial injuries 8.25 Cutaneous habronemiasis (or ‘summer sore’) 8.27 Diagnosis of diseases of the female reproductive tract 8.29 Perineal lacerations and fistulae 8.36 Ovariectomy (oophorectomy) Renal function and water balance in the normal horse • Water intake: varies greatly depending upon diet, ambient temperature, exercise, lactation, and psychogenic factors. Range: 4 to 6% of body weight daily. • Urination frequency: 7–11 times daily (foals urinate hourly and usually upon standing). • Urine volume: 1–3% body weight daily. • Urine character: pale yellow to brown (may darken upon standing); viscid due to mucus-secreting cells in the renal pelvis; often opaque due to suspension of calcium carbonate crystals. Horses fed legume hay form large amounts of calcium carbonate crystals and thus tend to have more opaque urine than horses fed grass or hay. • Equipment: 3.0–3.5 Mhz transducer for percutaneous examination (5.0 Mhz for foals); 5.0–7.5 Mhz transducer for examination per rectum. • Location: level of tuber coxae and 15th to 17th intercostal space for right kidney and paralumbar fossa for left kidney. Useful in diagnosis of cystitis, urinary calculi, sources of haematuria, etc. For male horses, a 100 cm, or longer, endoscope with an outside diameter no greater than 12 mm is used. Polyethylene tubing can be passed through the accessory chamber of the endoscope into a ureter for collection of urine (Figure 8.1). Usually Vim-Silverman-type or Tru-Cut-type biopsy needles are used. • Ultrasonically guided – the kidney is located ultrasonographically and the depth for needle penetration is measured, usually 3 cm and 7 cm for the right and left kidney, respectively. • Assistant-guided – the left kidney is grasped per rectum by an assistant who can feel the needle contact the kidney. • Serum urea nitrogen (SUN) (also known as blood urea nitrogen, BUN) – concentration rises when glomerular filtration rate (GFR) decreases. Not a reliable indicator of GFR because it is affected by non-renal factors. Anorexia and liver disease decrease concentration of SUN; increased protein intake increases concentration of SUN. • Serum creatinine – concentration rises when GFR decreases. Production (from muscle) is fairly constant. Not significantly absorbed or secreted by renal tubules. Therefore, creatinine concentration approximates GFR. Azotaemia (elevated concentration of SUN and/or creatinine) is not necessarily indicative of renal disease or the severity of renal disease. • Creatinine clearance – a reliable index of GFR in horses – determined by comparing creatinine concentrations in serum (Scr) and urine (Ucr) and the rate of urine production. Clearance cr = Ucr/Scr × mL/min/kg body wt. Reference range is 1.39 to 1.87 mL/min/kg. Concentrations below the reference range indicate decreased GFR. • Fractional excretion (clearance) of electrolytes – in renal tubular disease, electrolytes may be inappropriately excreted in urine. Because the clearance of creatinine is constant over time, the excretion of electrolytes can be compared to the excretion of creatinine. The formula for determining fractional excretion of an electrolyte (FEe) is: in which U = urine, S = serum, cr = creatinine, e = electrolyte. FEsodium is normally ≤ 1%; > 3% indicates abnormal renal excretion. • Urine to plasma or serum ratios for urea nitrogen (un), creatinine (cr) and osmolality (osm). Useful in distinguishing between renal and prerenal azotaemia, but measurements for renal and prerenal azotaemia may overlap. Based on a small number of azotaemic horses, reported measurements are: • Urinary enzymology. When renal tubular cells die, enzymes contained within these cells are released into the urine. Abnormally high concentrations of gamma glutamyltranspeptidase (GGT) indicate renal tubular damage. Comparison of UGGT concentration to Ucr concentration corrects for the effect of urine concentration on enzyme concentration. • Urinary specific gravity (USG) tends to be between 1.030 and 1.060, but fluctuates widely. Random urine samples may indicate hyposthenuria (USG <1.008), isosthenuria (USG 1.008–1.014) or hypersthenuria (USG >1.015). Foals tend to be hyposthenuric because they have a large fluid intake. Possible explanations for dilute urine in the adult horse are: • Urinary pH. Normally alkaline (pH is usually between 7.5 and 8.5). Urine may be acidic in cases of: The urine of foals tends to be acidic. Aetiology: Usually caused by intravascular volume depletion caused by haemorrhage, diarrhoea, endotoxaemia, inadequate water consumption, etc. Pathogenesis: Systemic hypotension stimulates the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone axis, release of antidiuretic hormone, and the sympathetic nervous system. As a result, blood flow is redistributed away from the renal cortex, and water is conserved. Diagnosis: Based on clinical and clinicopathological signs and rapid response to appropriate therapy. Aetiology: Acute renal tubular necrosis (RTN) resulting in acute renal failure (ARF) is caused by sustained or severe hypoperfusion, or nephrotoxins, or a combination of both. • Haemodynamic causes are most often initiated by endotoxaemia associated with some types of colic and acute diarrhoeal syndromes. 1. Plants – include red maple and oak trees, onions, and white snake root. Plants containing oxalates are potentially nephrotoxic, but oxalate-induced nephropathy is rare in horses. Deposition of oxalate crystals in kidneys, however, may occur secondarily to renal disease. 2. Heavy metals – mercury, lead, arsenic, and others. 3. Antibiotics – aminoglycosides (gentamicin, neomycin, amikacin), tetracycline, sulfonamides, cephaloridine, amphotericin B, and others. 4. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs – (NSAIDS) phenylbutazone and flunixin meglumine. NSAIDS are more likely to cause ARF when there is concurrent dehydration. 5. Pigments – myoglobin and haemoglobin. Haemoglobin and myoglobin are more likely to cause ARF if there is concurrent dehydration. • Acute pyelonephritis – most likely to occur in septicaemic neonates; Leptospira sp. and other bacteria can cause acute tubular necrosis in adults. Clinical signs of renal tubular necrosis: Clinical signs of acute renal failure due to renal tubular necrosis are non-specific – anorexia, depression, and weakness. These clinical signs can also be attributed to a precipitating haemodynamic cause such as colic or colitis. Toxins that induce acute renal failure are often not renal specific, and clinical signs associated with organ damage of other systems may predominate. Diagnosis: Acute renal failure caused by renal tubular necrosis is usually diagnosed on the basis of clinical signs, physical examination, ultrasonography, and laboratory evaluation. • Isosthenuria with concurrent dehydration and/or azotaemia. • Measurement of urinary enzymes. The UGGT/Ucr ratio is most commonly used. • Fractional excretion of sodium and phosphorus may be increased. • Glycosuria without hyperglycaemia. • Urine to plasma ratios of urea, creatinine, or osmolality may help distinguish prerenal from renal azotemia. • Treatment of the predisposing disease process (e.g. endotoxaemia, myositis). • Removal of suspected nephrotoxins. • Correction of fluid balance, serum electrolyte concentration, and acid–base abnormality. 1. monitoring central venous pressure. 2. monitoring for increases in body weight. 3. auscultating lungs for evidence of oedema. 4. observing for subcutaneous oedema. If the horse is anuric or oliguric despite rehydration, convert to polyuria with: Aetiology and pathogenesis: Chronic glomerulonephritis is the most frequent cause of CRF. Chronic glomerulonephritis does not always cause CRF. In one study 40% of equine kidneys examined at necropsy had microscopic glomerular lesions); there are two types of lesions: • Antiglomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis – (anti-GBMG) – is due to antibodies directed against the glomerular basement membrane. • Immune complex glomerulonephritis (ICG) – (the most common type) – is due to deposition of immune complexes along the glomerular basement membrane. Immune complexes may be associated with upper respiratory infections caused by Streptococcus spp. With either type, the glomeruli become inflamed and the glomerular membrane becomes thickened by fibroblasts. Chronic oxalate nephrosis – thought to be a consequence rather than a cause of CRF. Renal neoplasia – uncommon in horses. Types reported: adenocarcinoma (most common) and lymphoma. Clinical signs: Signs vary depending upon the aetiology • Peripheral oedema. Seen in horses with chronic glomerulonephritis; caused by extensive loss of plasma proteins through damaged glomerular capillaries. Triad of oedema, hypoproteinaemia, and proteinuria is referred to as the nephrotic syndrome. • Oral ulceration and dental tartar – occasionally observed. • Fever – may be seen with pyelonephritis. • Palpation per rectum and/or ultrasonic examination may reveal shrunken, firm kidney(s) with an irregular surface. • Ureteral discharge of bloody or purulent urine may be seen endoscopically in horses with pyelonephritis. Clinicopathological signs: Laboratory findings vary depending on the aetiology, stage of disease, and management factors. • Anaemia – due to decreased production of renal erythropoietic factor and shortened RBC lifespan. • Proteinuria – if glomerulonephritis is the cause of CRF, proteinuria is a consistent finding. Tubulointerstitial disease and pyelonephritis cause minimal proteinuria. • Horses with chronic tubulointerstitial disease are invariably isosthenuric (1.008–1.019). Isosthenuria eventually develops in horses with chronic glomerulonephritis. • The horse is usually azotaemic. • Concentrations of serum electrolytes may be abnormal. Diagnosis: Based on clinical and clinicopathological signs, endoscopic and ultrasonic examination, and renal biopsy. Treatment: Chronic renal failure is progressive. Clients should be advised that treatment is aimed at prolonging life rather than resolving the condition. • Supplementation of electrolytes based on periodic evaluation of serum concentrations of sodium, potassium, calcium, and bicarbonate. (If oedema develops, sodium should be restricted from the diet, even if the horse is hyponatraemic.) • Dietary supplementation with carbohydrates and fat. • Restriction of dietary protein to less than 10%. • Forced feeding in cases of anorexia. • Antimicrobial therapy for pyelonephritis. Selection of drug is based on culture and sensitivity and the ability of the antimicrobial drug to concentrate in renal tissue and urine. Clinicopathological findings: Examination of urine sediment for: • WBCs. More than 8 WBCs per high-power field of urine collected during urination or more than 5 when urine is collected by catheterization is evidence of inflammation. • RBCs. More than 8 RBCs per high-power field of urine collected during urination or more than 5 when urine is collected by catheterization is evidence of haemorrhage. • Large number of bacteria. Recovery of more than 10 000 colony-forming units per mL of urine collected by catheterization is diagnostic of urinary tract infection. Diagnosis: Clinicopathological findings confirm the presence or urinary tract infection, and physical examination (thickened bladder palpated per rectum) and/or cystoscopic examination (thickened, hyperaemic, or ulcerated mucosa) localize the infection to the bladder. • Correction of a predisposing cause if possible, such as removal of cystic calculi. • Antimicrobial therapy based on culture and sensitivity and ability of antimicrobial drug to concentrate in urine (such as aminoglycosides, trimethoprim/sulfadiazine, fluoroquinolones, penicillin and cephalosporins). Uroliths or calculi can form in the kidney (nephrolithiasis), ureters (ureterolithiasis), bladder (cystic urolithiasis) or urethra. If small, may be voided on urination or cause urethral obstruction. Most uroliths are composed of calcium carbonate and are spiculated and fragment easily (see Figure 8.2); those that also contain phosphate are smooth and hard and uncommon. • Mineralization of a nidus – renal disease may provide the nidus for nephro- and ureterolithiasis. NSAID-induced nephropathy has been speculated to be a cause of nidus formation in horses with nephro- and ureterolithiasis. Urolithiasis also may be the consequence of disease of the upper portion of the urinary tract such as pyelonephritis. • Abnormally low concentrations of natural inhibitors of mineral complexes in urine. High content of mucus produced by glands in the renal pelvis may prevent crystal aggregation. Clinical signs of nephrolithiasis and ureterolithiasis: Clinical signs of chronic renal failure (cachexia, anorexia, depression, dental tartar, oral ulcers, etc.). Calculi may cause or be the result of renal disease. • Surgical removal of a cystic calculus: • Urethrotomy at any site (for removal of urethral calculi). • Electrohydraulic or laser lithotripsy via ischial uretrotomy. Prevention of recurrence: Insuring complete removal of all fragments is important in preventing recurrence. Because urolithiasis may be the consequence of disease of the upper portion of the urinary tract, horses presented for urolithiasis should be examined for disease of the upper urinary tract. Treatment for pyleonephritis, if present, may prevent recurrence. Other preventive measures include: 2. Foals – bladder rupture and urachal tears, ureteral defects. • Prenatal distension of the bladder (perhaps caused by partial torsion of the umbilical cord) coupled with pressure on the full bladder during parturition leads to rupture of bladder or urachus. Affected foals are usually male. • Congenital bladder defects may be responsible for uroperitoneum of some foals. • Bladder and urachal rupture may occur due to lesions caused by urinary tract infections. • Tenesmus associated with g.i. disease may cause urachal tears. • Concentration of creatinine in peritoneal fluid containing urine is usually double that of serum creatinine (exception is foals evaluated early after bladder rupture). • Hypochloraemia, hyponatraemia, and hyperkalaemia in foals. These electrolyte abnormalities may not be seen in the adult. • Foals are usually, but not necessarily, azotaemic. • Calcium carbonate crystals may be seen in peritoneal fluid. • Clinical signs and clinicopathological findings. • Dye (methylene blue or fluorescein) placed into the bladder and subsequently recovered in peritoneal fluid. • Positive contrast cystography (do not use barium). • For diagnosis of suspected ureteral defects, exploratory laparotomy and cystotomy are performed. The ureters are infused with dye such as methylene blue, and examined for leakage. Intravenous pyelography is not very useful. Treatment: Cystorrhaphy and/or resection of urachus. Preoperative therapy might involve: 1. Measures to lower the potential for cardiac arrythmia caused by high serum concentration of potassium. • isotonic or hypertonic saline solution, IV. • 5% dextrose, IV and insulin. • enemas of sodium polystyrene sulfonate (a potassium-removing resin). • mask induction and anaesthesia with isoflurane or sevoflurane, which are less arrythmogenic than halothane.

Diseases of the equine urinary tract

8.1 Evaluation of the urinary system

Ultrasonographic examination

Distinguishing acute and chronic renal disease. Acute – swollen kidney with decreased echogenicity. Chronic – small, irregular kidney with increased echogenicity. A kidney should be considered to be abnormally small when it measures less than 10 cm.

Distinguishing acute and chronic renal disease. Acute – swollen kidney with decreased echogenicity. Chronic – small, irregular kidney with increased echogenicity. A kidney should be considered to be abnormally small when it measures less than 10 cm.

Diagnosis of renal cysts, urinary calculi, urinary neoplasia, uroperitoneum, etc.

Diagnosis of renal cysts, urinary calculi, urinary neoplasia, uroperitoneum, etc.

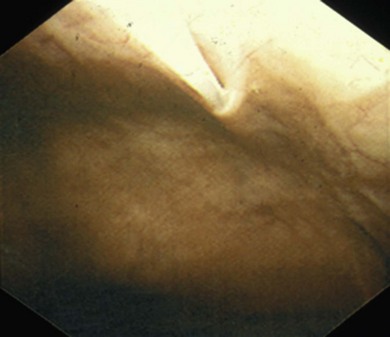

Endoscopic examination

Percutaneous renal biopsy

Laboratory assessment of urinary tract disease

Tendency toward hyponatraemia, hypochloraemia, and hyperkalaemia in renal failure. Degree of abnormality, if any, depends upon diet, appetite, and duration of renal failure.

Tendency toward hyponatraemia, hypochloraemia, and hyperkalaemia in renal failure. Degree of abnormality, if any, depends upon diet, appetite, and duration of renal failure.

Hypo, normo, or hypercalcaemia can occur in renal failure – depends upon diet, appetite, duration of failure, and age of the horse. Hypercalcaemia in renal failure is unique to the horse and is not understood.

Hypo, normo, or hypercalcaemia can occur in renal failure – depends upon diet, appetite, duration of failure, and age of the horse. Hypercalcaemia in renal failure is unique to the horse and is not understood.

Hypo, normo, or hyperphosphataemia can be seen in equine renal failure.

Hypo, normo, or hyperphosphataemia can be seen in equine renal failure.

Casts – presence of granular or cellular casts usually indicates renal disease; casts dissolve quickly in alkaline urine. Leukocyte casts are indicative of bacterial nephritis.

Casts – presence of granular or cellular casts usually indicates renal disease; casts dissolve quickly in alkaline urine. Leukocyte casts are indicative of bacterial nephritis.

Bacteria – the presence of more than 10 000 colony-forming units per mL of urine indicates urinary infection.

Bacteria – the presence of more than 10 000 colony-forming units per mL of urine indicates urinary infection.

White blood cells – the presence of small numbers (≤ 8/high-power field or 400× on a free catch or ≤5/hpf on catheter collection) is not abnormal.

White blood cells – the presence of small numbers (≤ 8/high-power field or 400× on a free catch or ≤5/hpf on catheter collection) is not abnormal.

Crystals – normal urine may contain crystals of calcium carbonate, triple phosphate, and oxalate.

Crystals – normal urine may contain crystals of calcium carbonate, triple phosphate, and oxalate.

8.2 Prerenal azotaemia

8.3 Acute renal failure due to renal disease

8.4 Chronic renal failure (CRF)

8.5 Cystitis

8.6 Urolithiasis

8.7 Uroperitoneum (see also Chapter 20)

.

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine