CHAPTER 18 Diseases Formerly Known as Rickettsial

The Rickettsioses, Ehrlichioses, Anaplasmoses, and Neorickettsial and Coxiella Infections

Tickborne Rickettsioses, Ehrlichioses, and Anaplasmoses

Several species within the genera Rickettsia, Ehrlichia, and Anaplasma are transmitted to vertebrate hosts through tick vectors. Accordingly the geographic distribution of disease usually follows the distribution of ticks infected with and capable of transmitting a particular organism. It is clinically useful to consider the known geographic distribution of vectors and the disease-causing agents they carry when determining differential diagnoses for infection. For example, for a dog presenting with neutrophilic polyarthritis in Wisconsin, infection with Anaplasma phagocytophilum (transmitted by Ixodes scapularis) would be a more likely diagnostic consideration, whereas in the southern United States, Ehrlichia ewingii (transmitted by Amblyomma americanum) would be a more likely differential diagnosis. Therefore practitioners should ensure that tests used to diagnose tickborne diseases (e.g., the “tick panel”) are appropriate for organisms prevalent in their area of practice or relevant to a particular patient. The distribution of some tick vectors of clinical significance in the United States can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/Ncidod/dvrd/rmsf/Natural_Hx.htm and http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5504a1.htm.

Rickettsioses: The Spotted Fever Group Rickettsia

Rickettsia rickettsii and RMSF in Dogs

Dogs are sentinels for the disease in people. Therefore veterinarians should notify owners and their physicians when RMSF is diagnosed in a dog (Box 18-1). Owners should be instructed with regard to proper tick removal, and crushing the tick should be avoided to prevent inadvertent exposure to infected hemolymph. Hands should be washed immediately after removal. Contact with infected dog blood by veterinarians and support staff could result in transmission of the organism, although this risk is presumably small. Wearing gloves, washing hands, avoiding aerosolization, and using zoonotic warning labels are recommended for handling samples from suspect cases.

BOX 18-1 Important points regarding Rocky Mountain spotted fever in dogs

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmoses

Canine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis Caused by Ehrlichia canis or Ehrlichia chaffeensis

Ehrlichia canis

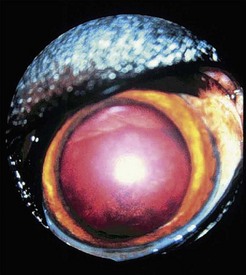

During the chronic phase, nonspecific signs such as weight loss, lethargy, and anorexia can recur. Disorders of primary hemostasis caused by thrombocytopenia and platelet dysfunction are prominent and include epistaxis, petechial or ecchymotic hemorrhages, hematuria, and melena. Fever, lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly may also be present. Dyspnea resulting from pneumonitis can also occur. Uveitis is common in dogs with E. canis infection. Other ocular abnormalities include corneal ulceration, hyphema, retinal hemorrhage, necrotic scleritis, decreased tear production, and orbital cellulitis (Figure 18-1). Importantly, ocular abnormalities can be the only presenting clinical sign. Neurologic signs include ataxia, seizures, head tilt, nystagmus, and conscious proprioceptive deficits. Hematologic findings include nonregenerative or rarely Coombs-positive immune-mediated hemolytic anemia. Like the acute and subacute phases of E. canis infection, thrombocytopenia can persist in the chronic phase. White blood cell counts can be normal, increased, or decreased, and pancytopenia may be present. Large granular lymphocytosis, which can be confused with leukemia, is noted on blood smears in some cases. Examination of bone marrow may reveal hypoplasia of the erythroid, myeloid, and/or megakaryocytic cell lines. Hyperplasia, particularly of the megakaryocytic cell line, may occur during the acute phase of the disease. Interestingly, bone marrow examination can sometimes reveal plasma cell hyperplasia, which can be confused with neoplasia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree