Chapter 27 Disease Problems of Small Rodents

The Diagnostic Challenge

Scheduling an Appointment

Healthy rodents are active during the waking part of the normal circadian cycle. Rats, hamsters, and mice are nocturnal, while Mongolian gerbils and degus can be active during both the day and night.80 When a sleep-deprived, drowsy, irritable animal is brought to the clinician, subtle signs of disease may be overlooked. It can be difficult to determine whether the subdued nature of the animal is related to an underlying illness or the circadian cycle. This is especially the case with hamsters. When possible, receptionists should schedule appointments for most rodents for the early evening hours. Appointment times are not as critical for gerbils and degus. By taking the time to explain the reasoning behind appointment scheduling to clients who are unwilling to make evening appointment, one may not only change their minds but also set the veterinarian-client relationship off to a good start.

Instruct the client to bring the rodent to the hospital in its own cage if possible. If not, ask the owner for photos or videos of the cage setup. Knowledge of the animal’s husbandry and sanitation is essential to obtaining a good clinical history. Only by seeing the cage, water supply, feed containers, bedding, and food can the clinician understand the environment in which the rodent is lives. Clients should be tactfully instructed not to clean the rodent’s housing in preparation for the appointment, because doing so they may inadvertently destroy information that is important for diagnosis and treatment.

Reception Area

The rodent’s sense of smell is well developed, and its world is rich in olfactory stimuli and pheromonal cues. Rodents exhibit an innate fear-like behavior when they detect chemosignals of predators. Major urinary proteins (MUPs) released by predators are detected by the rodent’s vomeronasal organ—which also detects pheromones involved in sexual behavior—triggering a fear response.74 Lab coats, stethoscopes, clothing, and hands can retain the scent of predators, which can induce defensive behavior in a rodent during the examination process. This is another reason to advise clients not to clean their pets’ cages before an appointment, as the familiar smell of seasoned bedding will afford comfort to the rodent. Alternatively, the opportunity for a habituated rodent to nestle next to the familiar smell of its owner can only be afforded in a quiet and safe waiting area.

Rodents are more sensitive to the effects of heat than those of cold. Even though wild hamsters and gerbils are desert-dwelling animals, their main method of thermoregulation involves escaping from the heat by burrowing or seeking cool places. Mice in particular are very sensitive to the effects of heat. Waiting areas as well as hospital cages for rodents should be kept relatively cool. An ideal ambient air temperature range is 68°F to 70°F (20°C-26°C).14

Medical History

Find out what owners know about rodents. Have they had rodents as pets before? Did they obtain their information on caring for their pet from a book, a pet store, family or friends, websites, or first-hand experience? Books about rodents for owners of all ages are presented in the “Suggested Client Reading” section at the end of this chapter. Websites about rodents often provide incomplete or misleading information; we cannot recommend any of these at present. Veterinarians should be aware of the current popular books and websites, as clients often have questions based on browsing these sources. Knowledge of your clients’ sources of information can further help you in judging their ability to provide an accurate history. Furthermore, pet owners report more confidence in information received from veterinarians compared with information from any other accessible source.51

• Where did the pet come from? a pet store? a laboratory?

• How long has the owner had the pet?

• Are there other pets in the household? If so, are they of the same species or a different species?

• What food does the owner give to the pet? Where is the food purchased?

• What food does the pet prefer and what does it actually eat?

• Where is the food stored and for how long?

• Who is responsible for feeding and cleaning? How routinely are these tasks done?

• How long have the signs of illness been apparent? Who first noticed them and why?

• Has the pet’s condition deteriorated, improved, or remained stable?

Many diseases are the result of poor or inappropriate feeding. When offered mixed-seed, vegetable, and fruit diets, pet rodents often selectively eat only one ingredient (e.g., sunflower seeds). In households with children, a regular feeding routine may not occur, and doting children may feed pets with inappropriate foods. Often owners are ignorant of the availability of specially formulated diets for pet rodents. These diets, which come in the form of pellets, are convenient and nutritionally balanced sources of nourishment. Feed manufacturers such as Oxbow Hay Products (Murdock, NE; www.oxbowhay.com), Kaytee (Chilton, WI; www.kaytee.com), and Mazuri (St. Louis, MO; www.mazuri.com) have developed diets for pet rodents that are available by direct order or from selected retailers. Diets developed for laboratory rodents can also be used. However, these diets are usually available only in 50-pound bags and can be purchased only from wholesale feed distributors. A list of laboratory rodent diet manufacturers can be found in the annual Buyers Guide issue of the journal Lab Animal (New York, NY) or its website www.labanimal.com. For critically ill, anorectic, or convalescing rodents, several products that can be fed by syringe or gavage tube, such as Critical Care (Oxbow) and Emeraid Omnivore (Lafeber, Cornell, IL; www.lafebervet.com) are available.

Clinical Examination

Seeing the condition of the rodent’s living quarters provides information that is helpful in reaching a diagnosis or a reasonable prognosis. Information obtained from a physical examination is limited because of a rodent’s size. However, the significance of the rodent’s history and husbandry can be evaluated only after thorough examination of the animal. With appropriate handling and a few specialized but simple pieces of equipment, the major organ systems can be thoroughly evaluated. If the same procedure is followed consistently, it eventually requires less and less time to perform.

The value of determining rectal temperature is questionable. Physical examination combined with attempts to measure rectal temperature causes stress, which can increase body temperature of rats by 3.5°F (2°C) above the nonstressed temperature.9 Core body temperature in rats and mice can vary daily from 96.5°F to 100.5°F (36°C-38°C) because of circadian variation, sex, and age.83 Rectal temperatures can be measured safely with the use of small semiflexible temperature probes connected to a digital clinical thermometer. The probes are reusable; they are available in polyvinyl chloride, nylon, and Teflon and range in size from 1 to 3 mm in diameter. They are ideal for monitoring body temperature when surgery on pet rodents is being performed. A list of manufacturers can be found in the annual Buyer’s Guide issue of the journal Lab Animal (New York, NY) or its website at www.labanimal.com. The manufacturers are listed under “Research/Animal Research Equipment/Temperature Probes.”

The clinician can obtain a small amount of blood for a smear and microhematocrit from a hind-limb skin stab, nail clip, or nick of the tip of the tail. An excellent website, written by exotic pet veterinarians, from which to obtain information on clinical techniques is Lafebervet.com Small Mammals (www.lafebervet.com/small-mammals/?p=265). Blood sampling in conscious rodents induces increases in blood pressure, heart rate, and body temperature, which may last up to 30 hours; therefore we often sedate or anesthetize patients to obtain samples.29 Low-dose acepromazine (0.5 mg/kg IM) administration results in peripheral vasodilation, making peripheral venipuncture easier. While some authors advise against using acepromazine in gerbils because it may induce seizures, there is no evidence of a proconvulsive effect in gerbils. Furthermore, clinicians reevaluating acepromazine administration and recurrence of seizure activity in epileptic dogs found no correlation.66

Technologic advances have made possible electrocardiography and accurate and sensitive recordings of heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure in research rodents.53 The cost of the equipment for performing these measurements and the invasive procedures that are often necessary for achieving the recordings prohibit routine use of these testing modalities in most veterinary practices. However, advances in high-resolution digital radiography that require relatively low radiographic exposures, developments in ultrasound, and the availability of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging have allowed diagnostic imaging to become a useful ancillary examination.84 Two excellent books designed to provide clinicians with normal anatomic and abnormal comparative diagnostic images are Diagnostic Imaging of Exotic Pets: Birds, Small Mammals, Reptiles54 and Radiology of Rodents, Rabbits and Ferrets: An Atlas of Normal Anatomy and Positioning.93

Diseases

General Comments

Diseases of Small Rodents Seen in Practice

The prevalence and types of small-rodent diseases seen in practice are quite different from what is seen in a research setting. Although this may seem rather obvious, much of the literature describing the maladies of pet rodents has been inferred indiscriminately from conditions seen in laboratory rodents. The diagnosis and treatment of pet rodents involves evaluation and care of an individual animal from a household, not the health management of rodents from a research colony. Derangements likely to be seen in practice include trauma-induced injuries, infectious and parasitic diseases, neoplasia, and problems related to nutrition and aging; genetic disorders are uncommon. Dermatologic conditions make up 25% of the cases in exotic pets presented for small-animal consultations in general practice in the United Kingdom.42 Natural infections that would be considered rare in a laboratory animal colony often are transmitted to pet rodents by other household animals and children; for example, cats and dogs are major reservoirs of dermatophytes,24 and humans are the natural host of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes, which are now often antibiotic-resistant.2 Rodents used for research are maintained in tightly controlled environments designed to reduce the impact of unwanted variables in animal experiments.14 However, pet rodents are generally exposed to temperature, humidity, and light-cycle changes; a broad range of foods; numerous microorganisms borne by animals and humans; and various types of handling. Rodents obtained from pet stores have had to endure the stress of overcrowding, transport, and on occasion temperature extremes, all of which put them at risk for disease. As a result, pet rodents exhibit a wider range of physiologic and pathologic responses than do rodents used for research. Consequently, the disease presentation of many pet rodents is atypical as compared with the classic experimental disease description.

Veterinarians must be discerning in their selection of information about rodents. Research-oriented scientific publications are often more obscuring than elucidating for small pet practice. Research articles often treat rodents as part of a herd or as experimental tools, and disease is diagnosed only by necropsy. Successful in vivo disease diagnosis and resolution are not addressed in such articles, and it is in this area that our understanding must be broadened. Exceptions to this observation are becoming more numerous since the first edition of this book was published. Articles with titles such as “What’s Your Diagnosis,” clinical case reports, and articles on clinical and surgical techniques in pet rodents are being published more frequently in laboratory animal medicine and mainstream veterinary journals worldwide. The Association of Exotic Mammal Veterinarians (AEMV) is affiliated with the Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine (www.exoticpetmedicine.com) and has expanded its website at www.aemv.org to include a searchable database of articles, disease descriptions, and current treatments.

Significant Diseases and Life Spans

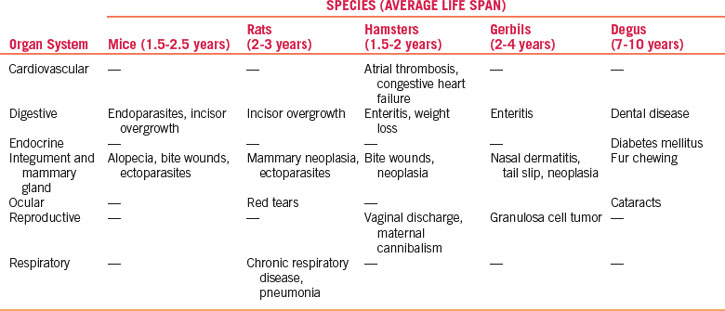

Pet mice, rats, gerbils, hamsters, and degus are subject to a limited number of naturally occurring medical problems. The most common spontaneous outbreaks of disease are caused, or at least stimulated, by shortcomings in husbandry. While caloric restriction has a significant impact on longevity in rodents as well as other species,73 the adverse effects of overfeeding on the early development of many spontaneous tumors and degenerative diseases has also been seen with “diabesity”—diet-induced obesity and type 2 diabetes.49,67 The more common problems seen in general practice, unique to each species, are listed and grouped by the primary organ system affected in Table 27-1. The average life span of each species also is given. Consistent with causes of death in dogs, unpublished surveys we conducted from rodent cases presented to the Animal Center in New York and the Foster Hospital for Small Animals at Tufts-Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine suggest that young (less than 1 year of age) pet rodents die more commonly of gastrointestinal and infectious causes, whereas older rodents (beyond the median life span) die of neoplastic causes.30 Traumatic injuries are frequent in all rodents of all ages.

As prey animals, rodents do not show obvious signs of pain or disease until they are near death. Consequently, sick rodents are often presented late in disease progression compared with earlier presentation in cats and dogs. We have found that indicators of death are a form of shock indicated by lethargy, decreased heart and respiratory rates, and a rapid drop in body temperature to below 91°F (33°C). In rodent aging studies, pronounced bradycardia (30% lower than normal) and hypothermia (13% lower than normal) are significant predictors of death 5 to 6 weeks before expiration.101 Treat this type of shock by warming the patient to restore normal temperature, infusing crystalloid fluids, and providing oxygen therapy. Successful treatment does not guarantee resolution of disease but may buy valuable time to establish a diagnosis and treatment plan for the underlying problem.

Prophylaxis for Small Rodents

Prevention of disease in rodents is far more successful than treatment. Disease prevention is primarily based on commonsense husbandry practices, such as purchasing healthy, genetically sound animals; supplying balanced fresh food appropriate in protein and caloric content; avoiding obesity; providing clean fresh water; furnishing adequate shelter, including shade from direct sunlight; avoiding drafts and extreme changes in temperature or humidity; keeping cages clean by preventing the accumulation of excess feces and urine; isolating sick animals from a group for treatment; and protecting vulnerable animals from more aggressive members of their group (e.g., young animals from older animals and male hamsters from female hamsters) or from natural predators living in the same household (e.g., mice from cats). Other sound husbandry practices include housing different species separately to prevent interspecies disease transmission (e.g., rats carry Streptobacillus moniliformis, a cause of septicemia in mice, in their nasopharyngeal cavities) and reducing obesity by limiting food intake and providing cage accessories (e.g., exercise wheels, tunnels, and ramps) that allow play and exploration. Companies selling environmental enrichment equipment and accessories for rodents include Otto Environmental (Milwaukee, WI; www.ottoenvironmental.com) and Bio-Serv (Frenchtown, NJ; www.bio-serv.com).

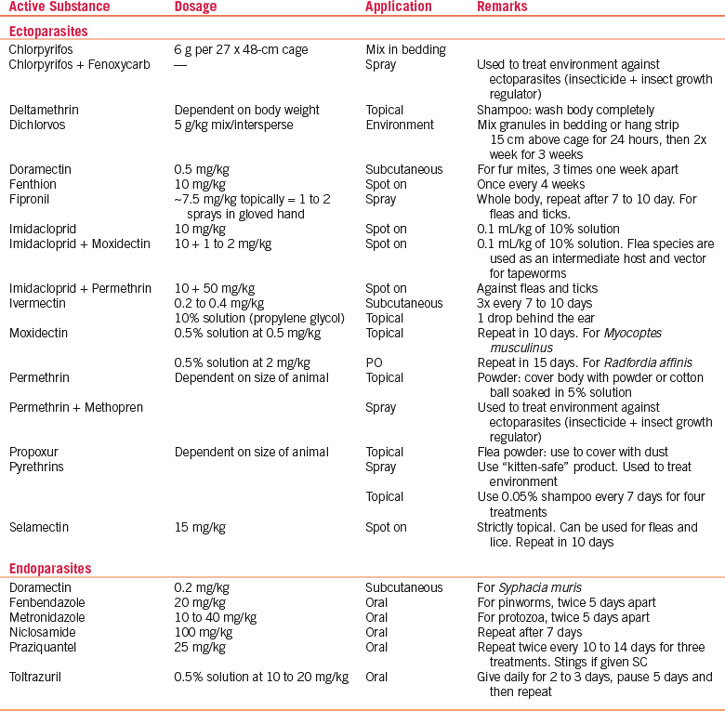

Unlike larger companion animals, pet rodents are not vaccinated. The introduction of avermectins (e.g., ivermectin, selamectin, moxidectin), although this agent is not approved for use in any rodent species, has allowed routine systemic treatment of pet rodents for pinworms, mites, and lice. For ecto- and endoparasite treatment recommendations, refer to Table 27-2.

Dental problems are commonly seen in pet rodents because of their continually erupting teeth. Overgrown, maloccluded, or malformed incisors are seen as spontaneous background lesions in 3% (females) to 9% (males) of outbred mice and 14.5% (females) to 10.5% (males) of outbred rats in chronic toxicology studies.62 Specially designed tabletop restraint devices, cheek dilators, mouth specula, dental drills, rongeurs, and filing-rasps for treating dental problems are now commonly available. For more information, see Chapter 32.

Clinical Signs and Treatment by Species

Mice

Integumentary System and Mammary Glands

Nearly all problems seen in pet mice are associated with the skin. A survey from a large diagnostic laboratory housing research animals indicated that skin disease in mice represents 25% of all diagnostic problem-solving cases (for all species) submitted.55 We categorize four groups of skin problems in mice: behavioral disorders, husbandry-related problems, microbiologic and parasitic infections, and idiopathic conditions. Behavioral, husbandry, and infectious causes of skin disease are relatively straightforward to diagnose and treat. However, many skin diseases characterized by chronic or ulcerated skin (often secondarily colonized by bacteria) are diagnosed as idiopathic. This group is commonly unresponsive to topical or systemic treatment, and affected individuals are often euthanatized. Most damage to the skin is done by toenails as the rodent scratches itself. It is difficult to prevent a rodent from scratching. The nails can be trimmed or filed to remove sharp ends, but attempts to fit the rodent with a bandage or protective wrap are often pointless, as these animals are adept at removing all bandages. Restraint collars can be used, but rodents are not able to eat easily with a collar in place and it will not be effective unless the underlying cause is detected and treated simultaneously.

Mice exhibit well-studied social and sexual behaviors. Social dominance, a form of behavior relating to the social rank and dominance status of an individual mouse in a group, is manifested as barbering and fighting. Barbering is commonly a condition seen in group-housed mice, where the dominant mouse nibbles off the whiskers and hair around the muzzles and eyes of cage mates. No other lesions are present, and only one mouse (the dominant one) retains all of its fur. Removal of the dominant mouse stops barbering; frequently, however, another mouse then assumes the dominant role. Barbering occurs during acts of mutual grooming in which one member of a mouse pair grasps individual whiskers or hairs with its incisors and plucks them out. Although plucking appears painful, recipients are passive in accepting barbering and even pursue conspecifics for further grooming.85 Barbering may also be seen associated with sexual overgrooming as a form of stress-evoked behavior, and lactating mice may display “maternal” barbering, produced in the process of suckling pups, in which alopecia is seen from tail to chin.47 Although rare in mice, consider infection with Trichophyton mentagrophytes in cases of alopecia that involve face, head, neck, or tail in all or just a few mice.22 Barbering has a genetic-based behavioral background, as aggressive inbred strains of mice do not use barbering in their behavior.47 In pet mice, barbering is often seen in female mice caged together. Male mice except littermates raised together from birth are more likely to fight, often very savagely, and inflict severe bite wounds on one another, especially over the rump, tail, and shoulders.

Mechanical abrasion resulting from self-trauma on cage equipment is a form of husbandry-related alopecia. Small patches of alopecia appear on the lateral surfaces of the muzzle, resulting from chaffing on metal feeders, poorly constructed watering device openings, and metal cage tops. Unlike barbering, dermatitis may also be associated with the alopecic area. Treatment consists of replacing the poorly constructed equipment with nonabrading equipment. Individually housed mice can display aberrant stereotypic behaviors such as polydipsia and bar chewing, which result in mechanical abrasion and alopecia. In these cases, environmental enrichment must be provided. Food items such as Lafeber parrot Nutriberries, Avicakes or Nutriforage (www.lafebervet.com) and toys such as running wheels or hollow tubes are helpful.

Most infectious causes of alopecia and dermatitis are associated with fur mites. Ectoparasites are common in mice purchased from pet stores.79 In affected animals, the hair is generally thin, especially on difficult-to-groom areas such as the head and trunk. The coat often has a greasy appearance; in cases of heavy infestation, noticeable pruritus and self-inflicted dermal ulceration may occur. Three mites are commonly seen: Myobia musculi, Myocoptes musculinus, and Radfordia affinis. The most clinically significant mouse mite is M. musculi. Infestations are usually caused by more than one species. Mites are spread by direct contact with infected mice or infested bedding. Diagnosis is based on the identifying adult mites, nymphs, or eggs on hair shafts with the use of a hand lens or a stereoscopic microscope. Adults and nymphs appear pearly white and elongated (being about twice as long as they are wide); eggs are oval and seen attached to the base of hairs or inside mature females.

Treat mite infestations with avermectins (e.g., ivermectin, selamectin) or milbemycins (moxidectin). Ivermectin (0.2 mg/kg SC or PO) twice at 10-day intervals is effective. Selamectin (10-12.5 mg/kg topical)35 or moxidectin (0.5 mg/kg topical78 or 2 mg/kg PO77) administered twice at an interval of 10 to 15 days are also effective (see Table 27-2).

Sometimes an owner presents a single pet mouse negative for primary ectoparasitic, bacterial, or mycotic infections with severe pruritus characterized by self-mutilation, dermal ulceration, necrosis, and fibrosis. Idiopathic ulcerative dermatitis is a well-recognized disease in black laboratory mice on a C57BL strain background with a characteristic distribution on the thorax and head. The cause is an underlying vasculitis attributed to immune complex deposition on dermal vessels.48 Dietary factors and dysregulated fatty acid metabolism have been implicated in the development of the disease and the severity appears to be modulated by dietary fat and vitamin E content. Gavaging affected mice with 0.1 mL per day of liquid from an essential fatty acid supplement containing omega-3 fatty acids was associated with regressed lesions and resolved pruritus in a small sample of affected mice.60 We have obtained good treatment results using a generic omega-3 fatty acid supplement at 0.1 to 0.2 mL PO q24h. The ulcers may heal with fibrosis and resulting skin contracture or progress to a Staphylococcus xylosus secondary bacterial infection.48,100

Progressive necrosing dermatitis of the pinna in mice, similar to idiopathic ulcerative dermatitis, may also be seen (Fig. 27-1).94 It occurs in outbred mice, and there is no strain background association. Initially a lesion on the dorsum of the pinna, resembling an engorged blood vessel or slight erythema, oozes serum and peripheral necrosis begins. Several days later the necrotic area sloughs and the pinna is left notched. In severe cases, the site becomes secondarily infected, the lesion becomes pruritic, and the mouse self-mutilates from the ear to the neck and over the shoulders. Treat these mice topically twice daily with of 0.2% cyclosporine in 2% lidocaine gel supplemented with 50 μg/mL gentamicin.

Ringworm, caused by Trichophyton mentagrophytes, is uncommon in pet mice. Lesions, when present, are most common on the face, head, neck, and tail. The lesions have a scurfy appearance with patchy areas of alopecia and variable degrees of erythema and crusting. Pruritus is usually minimal to absent and the lesions do not fluoresce under a Wood’s lamp.22 Skin swellings are usually tumors or abscesses. Needle biopsy often reveals the nature of the contents and allows diagnosis. Three opportunistic bacterial pathogens—Staphylococcus aureus, Pasteurella pneumotropica, and S. pyogenes—are often isolated3 and can cause abscesses in other organs (e.g., P. pneumotropica is sometimes associated with conjunctivitis, panophthalmitis, and swollen eye abscesses). Antibiotic therapy with penicillins or cephalosporins, concurrent with drainage and debridement of the abscess, is effective.

The most common spontaneous tumors associated with the skin are mammary adenocarcinomas, followed by fibrosarcomas. The incidence of mammary tumors varies according to the mouse strain and the presence or absence of mouse mammary tumor viruses; the incidence is as high as 70% in some strains.98 In wild and outbred mice, the incidence of fibrosarcomas ranges from 1% to 6%.41 Subcutaneous tumors are nearly always malignant and have often ulcerated by the time a diagnosis is made. Tumors can be treated by surgical excision, but the chance of recurrence is high and the prognosis is poor. Attempts to treat skin tumors in pet mice by radiation or chemotherapy have not been reported.

Digestive System

Endoparasites are relatively common in mice. However, only two parasites regularly encountered in the digestive tract, the protozoan parasites Spironucleus muris and Giardia muris, are considered pathogenic, even though they are not associated with clinical signs in immunocompetent hosts. Diagnosis is based on demonstrating characteristic trophozoites in wet mounts of fresh intestinal contents or feces. Treatment is metronidazole (two treatments of 10-40 mg/kg PO q5d) (see Table 27-2).

Pinworms are ubiquitous, considered nonpathogenic, and found frequently in mice purchased from a pet store.16 Two are commonly encountered in mice: Syphacia obvelata and Aspicularis tetraptera. Often the only indication of pinworm infestation is rectal prolapse due to straining. To establish a diagnosis of S. obvelata infestation, make a clear cellophane tape impression of the perianal skin. Adult S. obvelata females deposit ova around the anus, whereas A. tetraptera does not deposit its ova in this area and fecal smear or flotation is required to confirm a diagnosis. Ivermectin (2.0 mg/kg PO given twice at a 10-day interval) eliminates pinworms from mice. Ivermectin 1% is diluted 1:9 in vegetable oil to establish a concentration of 1.0 mg/mL; affected mice are dosed with a volume of 0.2 mL/100 g PO.31 The recommended package label dose for mice with ectoparasites (0.2 mg/kg given twice at a 10-day interval) does not eliminate pinworms (see Table 27-2).

Diarrhea is not usually seen in adult mice. Digestive disease in adult mice usually is caused by a varying combination of pathogenic and opportunistic infectious agents. Fecal flotation and fresh wet mounts of feces usually yield positive results and do not necessarily give a definitive diagnosis. However, these techniques are sometimes helpful in identifying heavy endoparasite infestations. Treatment is generally directed at clinical signs and consists of the judicious use of antimicrobials.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree