Chapter 24 Disease Problems of Chinchillas

Disorders of the Digestive System

Gastroenteritis and Dysbacteriosis

Identifying the underlying cause of gastroenteritis and dysbacteriosis is important to improve the therapeutic outcome and reduce the chance of recurrence. Consider performing whole-body radiographs, fecal parasite examination, fecal cytology, and fecal culture for enteric opportunistic pathogens (e.g., Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) in the initial diagnostic workup. Laboratory tests such as urinalysis, plasma biochemical analysis, and a complete blood count (CBC) can aid in diagnosing non-alimentary and concurrent metabolic disorders (e.g., hepatic lipidosis, ketosis, renal disease) that will influence the prognosis and therapy. Besides specific treatment for the primary underlying cause of gastroenteritis and dysbacteriosis, general treatment guidelines for all cases of gastrointestinal disease should include replacing fluid deficits and maintaining normovolemia by parenteral and enteral fluid therapy, nutritional and caloric support, and managing pain (buprenorphine 0.03-0.05 mg/kg SC q8h) if a painful condition is suspected.

Constipation

Constipation is a common problem in chinchillas.16,61 Reduced output or absence of fecal pellets that are smaller and irregular in size is commonly seen. Sudden changes in diet, an inappropriate diet, or infectious causes can lead to dysbacteriosis, gastroenteritis, and ileus and consequently constipation. Underlying causes include anorexia, dental disease, and gastroenteritis.16,61 Abdominal palpation may reveal firm ingesta in the cecum and a tense abdomen. Animals often become anorexic and progressively lethargic. An important differential diagnosis for complete lack of fecal output in chinchillas is intestinal intussusception.

General guidelines for the treatment of gastrointestinal disease apply for constipation. The aim is to rehydrate the gut by fluid therapy. Consider enteral fluid therapy (100 mL/kg PO q24h divided in 4-5 doses) in chinchillas with constipation to stimulate a gastrocecal reflex and rehydrate dehydrated ingesta.50,77 Abdominal massage and regular exercise may also be helpful.

Diarrhea and Soft Feces

Diarrhea and soft feces are common presentations in chinchillas. Besides infectious causes (e.g., parasites, bacteria), inappropriate feeding or sudden changes in diet with resultant dysbacteriosis commonly cause soft feces. Overfeeding of fresh green feed or items high in simple carbohydrates can result in dysbacteriosis and soft feces. Feces smeared on the cage resting board of a pet with or without matted, fecal-stained perianal fur are often the first signs the owner notices. The animal might be otherwise normal or, in chronic and severe cases, it can be anorexic, dehydrated, and depressed. Rule out infectious causes based on the history and by appropriate diagnostic testing. Intestinal secondary yeast overgrowth, caused by Cyniclomyces guttulatus (previously Saccharomycopsis guttulata), which lines the stomach, is often seen in chinchillas with soft feces.145 However, increased numbers of this yeast in chinchillas with diarrhea or soft feces is considered secondary rather than a cause, usually promoted by an underlying disease process.38 Offer well-dried, high-quality grass hay if the animal is still eating. Consider treatment with nystatin (100,000 IU/kg PO q8h for 5 days) if C. guttulatus overgrowth is very high or no response to initial treatment is seen.

Tympany

Tympany of the stomach and intestine is less common in chinchillas compared with other rodents or rabbits. Tympany is often secondary to gastroenteritis, dysbacteriosis, ileus or luminal obstruction or, very rarely, intestinal torsion.86 The affected animals usually has a distended and tense abdomen. In severe cases, depressed and dyspneic chinchillas may lie on their sides. Signs of shock may be present. Prognosis depends on the severity and duration of tympany but is usually poor in severe or chronic cases. Institute treatment based on general guidelines for the management of gastroenteritis. Although gastric decompression is recommended for severe cases of tympany, this might result in collapse and death in a decompensated patient. Do not use motility-enhancing drugs (e.g., cisapride) if an infectious or obstructive cause cannot be ruled out.

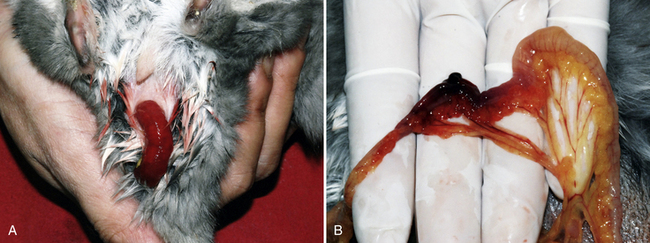

Rectal Tissue Prolapse and Intussusception

Rectal tissue prolapse and intestinal intussusception frequently occur together, secondary to dysbacteriosis, enteritis, constipation, or diarrhea (Fig. 24-1).82,128 Intussusception of the descending colon and rectum is associated with most cases of rectal prolapse; however, the small intestine can also be affected.82,94,128 Abdominal palpation might reveal a turgid cylindrical mass reflecting the intussuscepted portion of the intestine.82 The amount of intestine involved in the intussusception can be extensive and the affected portion is usually cyanotic, congested, and, in advanced cases, often nonviable (see Fig. 24-1, B).82 Besides treatment of the primary underlying cause, surgically correcting the intussusception is critical: intestinal resection and anastomosis may be necessary. Simple replacement or resection of prolapsed rectal tissue is insufficient. Assess the prolapsed tissue for viability and trauma. If an intussusception is ruled out, carefully clean and soak the edematous prolapsed rectal tissue in a concentrated sugar solution (50% dextrose). Replace the prolapsed tissue and place a perianal purse-string suture.94,128 Successful outcome after laparotomy and manual correction of more proximally located intussusceptions has been reported.82 However, the prognosis remains poor in most cases and the outcome will depend on the location and duration of the intussusception, viability of the prolapsed and intussuscepted tissue, and the underlying primary cause. Recurrence and rapid deterioration of affected animals is unfortunately common, since rectal prolapse and intussusception usually reflect an acute complication of a more chronic underlying primary problem.

Esophageal Disorders

Because chinchillas cannot vomit, food items such as raisins, fruit, and nuts as well as bedding material and ingested placentas in postparturient females can become stuck in the oropharynx and upper esophagus.20,38 Clinical signs are a sudden onset of anorexia, drooling, retching, and possible dyspnea. Removal of the foreign material is usually curative and the prognosis is good if the problem is dealt with early.38 Megaesophagus was diagnosed in a 2-year-old chinchilla that presented for recurrent acute episodes of dyspnea and nasal discharge.63 During hospitalization, the animal regurgitated food material episodically, followed by dyspnea, retching, gasping, and nasal discharge. Upper gastrointestinal contrast radiography aided the diagnosis of megaesophagus in this animal (Fig. 24-2).

Dental Disorders

Dental disease is commonly diagnosed in chinchillas and can affect animals of all ages (see Chapter 32).61 In two studies, abnormalities related to subclinical dental disease were detected in 35%21 and 33%61 of apparently healthy chinchillas presented for routine physical examination. Nutritional (e.g., less abrasive diet in captivity) and genetic causes have been proposed as the predisposing factors for the development of dental disease in chinchillas.24 Tooth elongation and its secondary complications, affecting the reserve or the clinical crown or both, is the underlying cause for most clinical signs associated with dental disease. Despite sometimes dramatic elongation of reserve and clinical crowns of the cheek teeth, animals often have no difficulty eating and maintain a good body condition until severe changes and complications, such as soft tissue trauma from sharp dental spikes or periodontal infection, have occurred.

Common clinical findings associated with dental disease in chinchillas are reduced food intake, changed food preferences toward more easily chewed feed items, weight loss, reduced fecal output with smaller, irregularly shaped fecal pellets, saliva-stained skin and fur with crusting and alopecia of the perioral area, wetting and crusting of the chin (“slobbers”) and forefeet, epiphora, poor fur condition, and fur chewing.21,61 On clinical examination, palpable irregularities of the ventral borders of the mandible, and overgrown or irregular occlusal surfaces of the incisor teeth may be found.21,61 Facial abscesses of periodontal origin are seen infrequently but can occur.22,61

A limited examination using a pediatric laryngoscope, otoscope, or vaginal speculum can be performed in a conscious animal, but up to 50% of intraoral lesions can be missed.21 Instead, perform a thorough examination of the oral cavity under general anesthesia. Endoscopic-guided intraoral examination (stomatoscopy) provides superior visibility and increases the chance for detection of pathologic lesions (see Chapter 32). Common intraoral findings involving the cheek teeth include coronal elongation, changes of the occlusal surface, formation of sharp spikes buccally and less commonly lingually on the edges of the occlusal surfaces, and widened interproximal coronal spaces that facilitate impaction and promote the development of periodontal disease.22,61 Resorptive and caries-like lesions of the cheek teeth are common in chinchillas; loss of tooth substance or brown discoloration of occlusal and interproximal tooth surfaces is seen.21–2361 Erosions of the buccal mucosa, gingival hyperplasia, and gingival pocketing are common intraoral findings secondary to dental disease.21,61

Evaluate radiographs or computed tomography (CT) scans of the skull in any chinchilla with a history or clinical signs suggestive of underlying dental disease. Some clinicians like to use anatomic reference lines for objective interpretation of skull radiographs and staging of dental disease in chinchillas.11

The prognosis for chinchillas diagnosed with dental disease depends on the severity of dental disease, the animal’s general condition, and owner compliance. Repeated intraoral examinations and treatments under general anesthesia at varying intervals, often for the life of the animal, are usually necessary to control complications of dental disease and maintain an acceptable quality of life for the animal. The goals of therapy should include reduction of periodontal infection and soft tissue trauma, which both lead to discomfort and pain, and either recovering or maintaining the animal’s ability to eat unaided. After removing spikes and reducing elongated crowns (see Chapter 32), probe interproximal spaces and gingival pockets and remove impacted debris. Rinse cleaned gingival and periodontal pockets carefully with 2% hydrogen peroxide or diluted chlorhexidine solution.115 Instilling Doxirobe gel (Pfizer Animal Health, New York, NY) in deep (>5 mm) gingival and periodontal pockets may help delay reimpaction with debris and reduce periodontal inflammation.144 If evidence of significant periodontal infection exists, begin systemic antimicrobial therapy with antimicrobials that are effective against anerobic bacteria predominating in periodontal infections (e.g., penicillin G benzathine 50,000 IU/kg SC q5d).133 Limit extraction of cheek teeth to those that are severely diseased and mobile. Removal of cheek teeth may lead to an increased rate of coronal overgrowth of the opposing cheek teeth, owing to the lack of attrition, and can necessitate more frequent coronal crown reductions.

Eye Disorders

Epiphora

Epiphora (“wet eye”) is a common condition in chinchillas, usually characterized by unilateral serous discharge, wetting of the periocular fur, and potentially periocular alopecia and dermatitis. Because of secondary bone remodeling, a common underlying cause for epiphora is elongated apical reserve crowns of both the maxillary premolar and first two molar teeth, causing complete or partial compression and consequent obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct.22,25 In contrast to rabbits, obliteration of the nasolacrimal duct at the level of the apical portion of the maxillary incisor is uncommon in chinchillas.16,25,61 Because of the very small size of the lacrimal punctae, visualizing and catheterizing the lacrimal duct for flushing is very difficult and not routinely performed.22 Treat concurrent or underlying infection and inflammation with appropriate topical antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (see Chapter 37).

Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis is common in chinchillas. Irritation from excessive sand bathing, inadequate cage ventilation, or underlying nasolacrimal duct obstruction is often the cause. A variety of bacteria can cause primary bacterial conjunctivitis. Conjunctivitis caused by P. aeruginosa as a localized infection or as part of a systemic infection has been reported.28,138 Depression and anorexia, commonly seen in cases of pseudomonal conjunctivitis, indicates possible underlying systemic infection.28,138 There is controversy as to whether P. aeruginosa is part of the normal conjunctival flora, which consists predominately of gram-positive organisms including Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Corynebacterium species.75,85,91 Fluorescein staining is necessary to rule out damage to the corneal surface. Submit a conjunctival swab for bacterial culture and antibiotic susceptibility testing. Treatment includes thoroughly lavaging the conjunctival sac with physiologic saline and applying a topical broad-spectrum antibiotic (e.g., gentamicin) that provides coverage against gram-negative and multiresistant bacteria. Access to a sand bath should be restricted until the chinchilla is fully recovered. Early recognition, systemic antibiotic therapy, and supportive care are critical for chinchillas suffering from systemic Pseudomonas infection.28

Corneal Disorders

Corneal damage and keratitis secondary to trauma are common clinical findings in chinchillas, usually associated with blepharospasm, discharge, and conjunctivitis.35 The large, prominent corneal surface possibly predisposes chinchillas to corneal trauma. Excessive sand bathing, the provision of inappropriate sand for bathing, and inappropriate housing conditions should be considered as possible underlying causes.35,135 Diagnosis is by fluorescein staining of the corneal surface. Avoid direct contact between fluorescein-impregnated test strips and the corneal surface because this can lead to false-positive results.35 Rule out possible nontraumatic underlying causes (e.g., exophthalmos, trichiasis) to avoid reoccurrence. Treatment of acute superficial lesions includes application of antibiotic ophthalmic formulations. In cases of chronic nonhealing ulcers, consider corneal debridement or grid keratomy after controlling any potential bacterial infection.

Other Eye Disorders

Exophthalmos can be caused by a retrobulbar process or increased intraocular pressure. The chinchilla’s orbit is shallow, and manual retraction of the eyelids can cause iatrogenic proptosis of the globe.135 Retrobulbar periapical abscesses of the maxillary cheek teeth—causing exophthalmos—are less common in chinchillas than in guinea pigs or rabbits.21 A rare retrobulbar taenia cyst has been described.56 Primary glaucoma has not been reported in chinchillas. Secondary glaucoma is uncommon but has been reported, and reference intervals for intraocular pressure in chinchillas have been published.85,111

Uveitis and panophthalmitis are uncommon diagnoses in chinchillas and may be caused by trauma or a systemic inflammatory process.135 A rare case of human herpesvirus I infection in a chinchilla, causing ulcerative keratitis, retinitis, neuritis and meningoencephalitis, has been reported.140

Lenticular changes such as cataracts, nucleosclerosis, and lens sutures can occur in chinchillas.37,81,85,111 Because diabetogenic cataracts have been reported in chinchillas, diabetes mellitus should be ruled out in animals presenting with uni- or bilateral cataracts.37

Asteroid hyalosis of the vitreous humor, in which lipid-calcium particles are formed as part of a degenerative process, can occur in older chinchillas.111

Ear Disorders

Chinchillas are used as animal models for human otologic disease research, including hearing loss and otitis media.3,5 Multiple studies on the pathophysiology and antimicrobial treatment of experimentally induced otitis media in chinchillas are available.1,2,4,19,60 Clinical signs caused by otitis externa, media, and interna can range from external ear canal discharge, head shaking, and mild head tilt to facial paresis and severe neurologic deficits.138 Otitis externa is often the result of a perforated tympanic membrane secondary to otitis media; therefore discharge from the ear canal should prompt the clinician to rule out a middle ear infection.

Skull radiographs in dorsoventral projection or, preferably, computed tomography (CT) scans are used for the diagnosis of otitis media (Fig. 24-3). Otoscopic examination of the external ear canal and tympanic membrane may reveal purulent exudate and inflammation of the external ear canal. A variety of bacteria may be cultured from the middle ear in chinchillas diagnosed with otitis media. Clinical signs associated with an epizootic outbreak of P. aeruginosa-induced otitis media and interna in a breeding facility were ear discharge, conjunctivitis, neurologic signs, and sudden death due to septicemia.138 Treatment of bacterial otitis media and interna remains challenging because of the formation of biofilms in the middle ear that can reduce the efficacy of antimicrobial drugs.3 Bacterial isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility testing are critical. Minimally invasive access to the middle ear through the dorsal roof of the tympanic bulla is a common surgical procedure in chinchillas used for human otologic disease research, and this technique can be used in a clinical setting for sterile sampling of the middle ear.15 Antibiotic selection should be based on susceptibility of the isolated organisms and the potential of the available drugs to eliminate bacteria effectively from the middle ear. Recommendations of fluoroquinolones and chloramphenicol for the treatment of otitis media in chinchillas are based on anecdotal evidence. Azithromycin (30 mg/kg PO q24h) reaches tissue levels high enough to recreate sterile conditions within the middle ear of chinchillas.4,19

Respiratory System Disorders

Primary respiratory disease is uncommon in pet chinchillas. Historically, bacterial pneumonia was an important cause of mortality in ranched chinchillas and is still significant if husbandry is inadequate.8,14,16

Pneumonia is usually bacterial in origin. Important predisposing factors are poor husbandry, such as overcrowding, inadequate ventilation, and poor hygiene. Predominately gram-negative organisms have been isolated from chinchillas diagnosed with pneumonia.7,8,58 Clinical signs that may are tachypnea, dyspnea, and, in severe cases, open-mouth breathing. Presenting animals are often in poor body condition and have a poor hair coat. After ruling out other causes, such as congestive heart failure, initiate systemic antimicrobial therapy. Recommendations for treatment include oxygen therapy, systemic antibiotic therapy, and nebulization with antimicrobials (e.g., gentamicin, tobramycin). Once dyspnea is evident and an animal is in poor body condition, indicative of chronic disease, the prognosis is guarded to poor.

Nasal discharge is relatively uncommon in chinchillas but can be associated with underlying dental disease, nasal foreign bodies, rhinitis, or lower respiratory tract disease. Base treatment on the underlying cause. Recurrent pneumonia and mucopurulent nasal discharge were associated with a megaesophagus in a 2-year-old chinchilla (see Fig. 24-2).63

Reproductive System Disorders

Endometritis and Pyometra

Pet chinchillas may develop endometritis and pyometra. Affected animals can present with a history of acute onset of depression and anorexia or with mild lethargy or behavioral changes.69,136 Clinical signs vary, but an open vulva and vaginal discharge are present in most cases. Vaginal discharge can range from mucoid or mucopurulent to hemorrhagic. Anogenital fur staining may occur. Uterine enlargement or vaginal discharge may be evident on abdominal palpation. Radiographs and abdominal ultrasonography are helpful to evaluate the uterus. Vaginal cytology can be useful to differentiate metritis from physiologic vaginal discharge during estrus.9 Ovariohysterectomy has been recommended as the treatment of choice for endometritis and pyometra.136 In cases of mild endometritis with vaginal discharge, if the animal is in good condition, systemic antimicrobial therapy based on culture and susceptibility can be attempted.51 As in other species, prognosis will depend on the underlying and coexisting causes, such as hepatic lipidosis, ketosis, and possible complications in severe cases such as sepsis.

Dystocia

Signs of dystocia in chinchillas include restlessness, frequent crying, constant attention to the genital region, and a widened vaginal opening. Allantoic fluid or mucoid-hemorrhagic discharge from the vagina is often seen. Dystocia is usually associated with the presentation of a single oversized fetus or malpresentation of one or more kits.20 Uterine inertia has also been reported as a cause of dystocia.113 Use radiographs to assess the number, size, and position of the fetus(es). In an uncomplicated dystocia, lubrication and gentle traction of the fetus with feline obstetric forceps may correct the condition. Attempt treatment for uterine inertia with oxytocin (0.5-1 IU/kg SQ) and calcium gluconate (25-50 mg/kg SC diluted). Surgical intervention is imperative if the chinchilla is in labor for longer than 4 hours. Pet chinchillas respond well to cesarean section.113

Fetal resorption, mummification, retention, and abortion are common in chinchillas.137 Fetal death may be caused by a variety of infectious and noninfectious causes. Incompletely reabsorbed, retained, or mummified fetuses can remain in the uterus for extended periods and can predispose to sterility and endometritis.

The ovarian bursa in chinchillas is underdeveloped and a case of an ectopic pregnancy has been reported.43 Several reports describe pulmonary trophoblastic emboli as incidental findings during postmortem examination in chinchillas; they have no clinical significance.57,132 While neoplasia in chinchillas is rare, several reports describe uterine leiomyosarcomas.

Penile Disorders

Accumulation of hair (“fur ring”), smegma, or both around the base of the glans penis when it is enclosed within the prepuce is common in chinchillas (Fig. 24-4). Fur rings can be found in single-housed as well as breeding males. Male chinchillas that groom excessively, strain to urinate, frequently produce small amounts of urine, or repeatedly clean the penis may have a fur ring.59 The ring of hair can eventually stop the penis from retracting into the prepuce. In severe cases, an engorged penis is seen protruding from the prepuce, resulting in paraphimosis.59 The condition is not only painful but also may cause urethral constriction and acute urinary blockage. Treatment includes carefully removing any fur or debris from the penis. Topical ointments or gels are applied to prevent drying of the exposed penis and everted prepuce. For cases with underlying infection (Fig. 24-5), use systemic antimicrobial treatment. Complete resolution of infection and swelling is possible with topical and systemic treatment, but it may require long-term attention. Always examine the penis of male chinchillas during routine physical examination and remove any accumulated fur or secretions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree