Chapter 35 Diagnostic Imaging

General Considerations

Chemical restraint is recommended for most small mammal radiographic examinations. Isoflurane or sevoflurane delivered by face mask is convenient and safe. In excitable or fractious animals, induce anesthesia in an induction chamber and use a face mask for maintenance. In other instances, injectable agents can be used for short examinations. Sedative protocols are detailed in Chapter 31. For lengthy procedures, intubating the animal is preferable, but this can be difficult or impossible in small species.26

Depending on local and state laws, manual patient restraining techniques can sometimes be implemented for making radiographs. Whether the patient is manually or chemically restrained, strict adherence to radiation safety principles should always be maintained. The basics of radiation safety can be boiled down to time, distance, and shielding.27 Efforts should be made to reduce the patient and restrainer’s time exposed to ionizing radiation. Lower exposure settings and reduced number of retakes are effective ways to reduce time of exposure (see “Digital Radiography,” below). Increasing the distance from the primary source of radiation is the single most effective method to reduce exposure to the restrainer. If a patient is properly positioned without manual restraint, there is no reason for anyone to be close to the radiology table during exposure, even if a lead apron is worn. One step back from the table exponentially reduces one’s exposure to the radiation.6 Barriers (shielding)—such as lead gloves, aprons, and walls—are effective means of radiation protection. However, it must be stressed that lead gloves will not protect the restrainer from the primary beam radiation (the radiation outlined by the collimator light). Leaded garments will protect only from the scatter radiation emanating from the tube, patient, and table (Fig. 35-1).

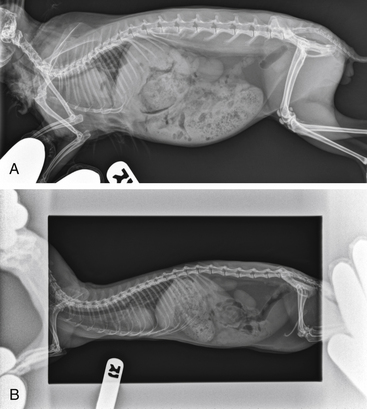

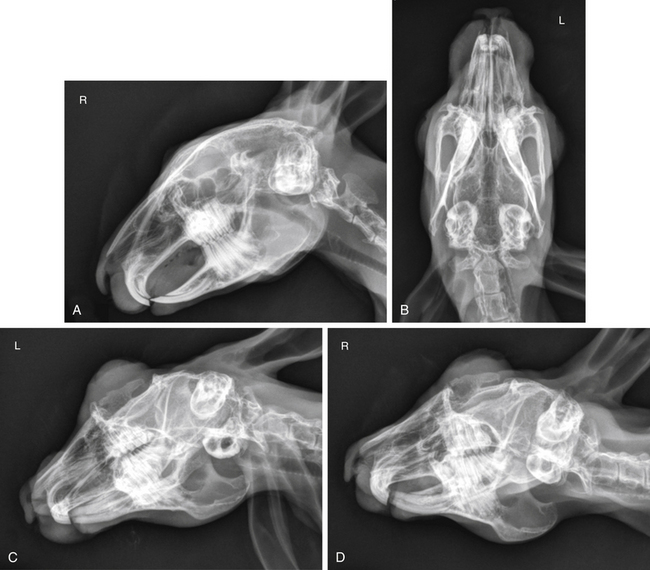

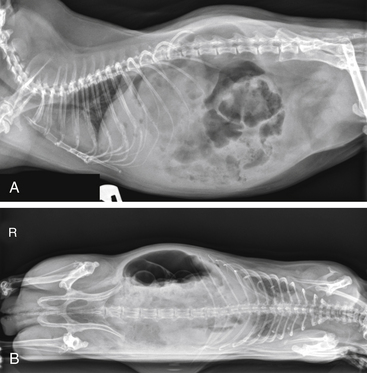

Proper restraint allows for proper positioning. Improper positioning is a common source of radiographic misinterpretation. In radiography, orthogonal (90-degree) projections allow us to pinpoint the exact location of an abnormality (is it on the patient’s skin or in the body?). The more views we obtain, the more confident we can be of the presence of a radiographic abnormality (Fig. 35-2). Obliquity should be minimized, especially for ventrodorsal (VD) or dorsoventral (DV) projections. Properly positioned VD and DV radiographs are ideal for assessing symmetry from left to right.11,26 Symmetry is also crucial for interpreting cross-sectional imaging modalities like CT and MRI.

Which Imaging Examination to Perform

Uncommon species presented to our facility’s exotic animal department can pose diagnostic challenges. Facing this challenge, the radiologist and primary care veterinarian work as a team to determine which imaging exam will provide the most useful information. A review of the advantages and drawbacks of various imaging modalities is presented below to illustrate this decision-making process.

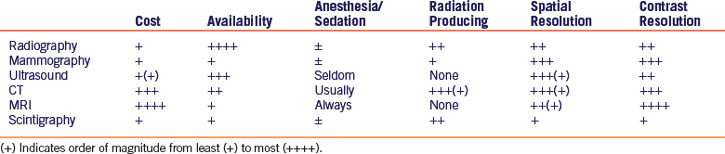

Practical considerations like anesthetic requirements, cost, and availability are crucial to the decision-making process. Other considerations that may not be readily obvious are the objective criteria used to assess image resolution (Table 35-1).

Image Resolution

Contrast Resolution

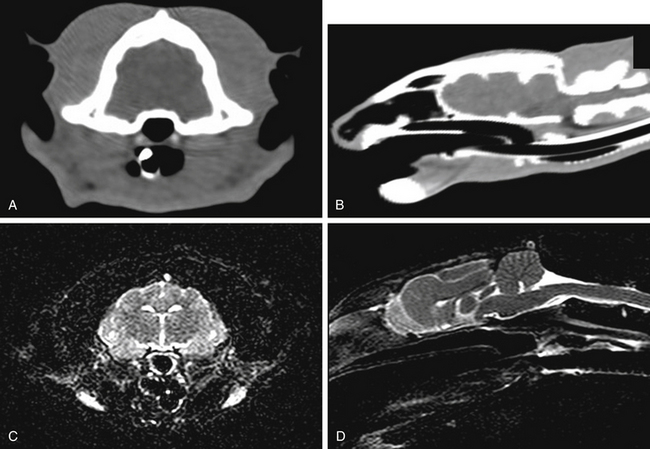

Contrast resolution refers to the ability to distinguish between shades of gray in an image. For example, MRI, which has exquisite contrast resolution for soft tissues, is the modality of choice for identifying subtle changes in gray and white matter of the brain (Fig. 35-3).

The Modalities

Radiography

A few points should be made in regard to the radiographic imaging of very small patients. In all veterinary patients but particularly in small mammals with increased respiratory rates, motion during exposure is a problem. Therefore x-ray equipment capable of producing 300 milliamperes (mA) in 0.008 second is a minimum requirement.25,26 Most radiographs can be exposed for 0.008 to 0.016 second with excellent results. Incremental adjustments of kilovoltage are necessary through a range of 45 to 70 kilovoltage peak (kVp). A unit’s focal spot can be thought of as an adjustable narrowing of the beam of radiation emanating from the tube. A small focal spot allows for better spatial resolution.6,25 However, small focal spots limit the total milliamperes and are not recommended in larger patients. A telescoping x-ray stand that can be moved along the x-ray table and adjusted in height is helpful. The ability to change the focal-film distance (distance from the x-ray tube to the film) is useful to produce magnified views of anatomic areas of interest. Effective magnification is possible only with small focal spots. Horizontally directed x-ray beams are helpful in evaluating gravity-dependent (fluid and sediment) and non-gravity-dependent (gas) structures (Fig. 35-4). A horizontally directed beam can also provide safe, effective restraint for fractious patients or patients that can remain standing.12,29

Strategies for optimizing spatial resolution in film-based radiography focus on appropriate film-screen combinations. High-speed film or cassettes used in most veterinary practices allow for less exposure but do not provide the resolution desired for small patients. Slower-speed film and cassettes provide better detail but require greater exposure. Fine or detail-intensifying screens can be used for radiographs of smaller patients (e.g., Curix Fine, Agfa, Orangeburg, NY; Quanta Detail, E.I. DuPont, Wilmington, DE; Lanex Fine, Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). These screens, combined with the proper x-ray film (Curix Detail RPIL, Agfa; Cronex 10, E.I. DuPont; TMG film, Eastman Kodak) maximize anatomic detail. For ultrafine detail in exotic pet radiography, the Min R mammography system (Eastman Kodak) can be used. Mammography may not be as available as general radiography but has superior spatial and contrast resolution (see Table 35-1).25,26

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree