Chapter 10 Diagnostic Analgesia

Local Anesthetics: Pharmacology and Tissue Interactions

Strategy, Methodology, and Other Considerations

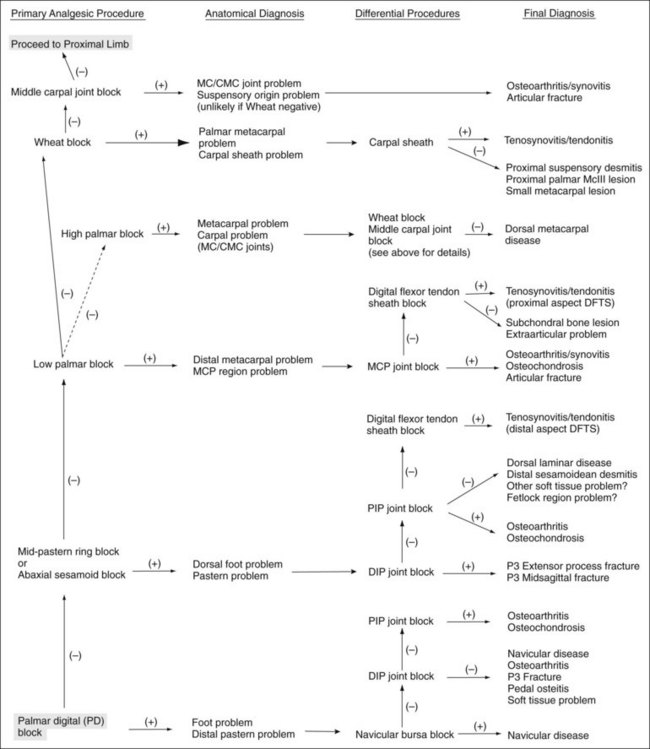

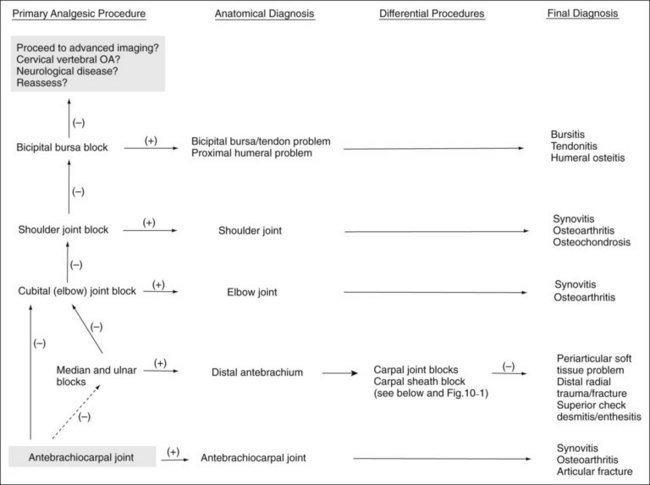

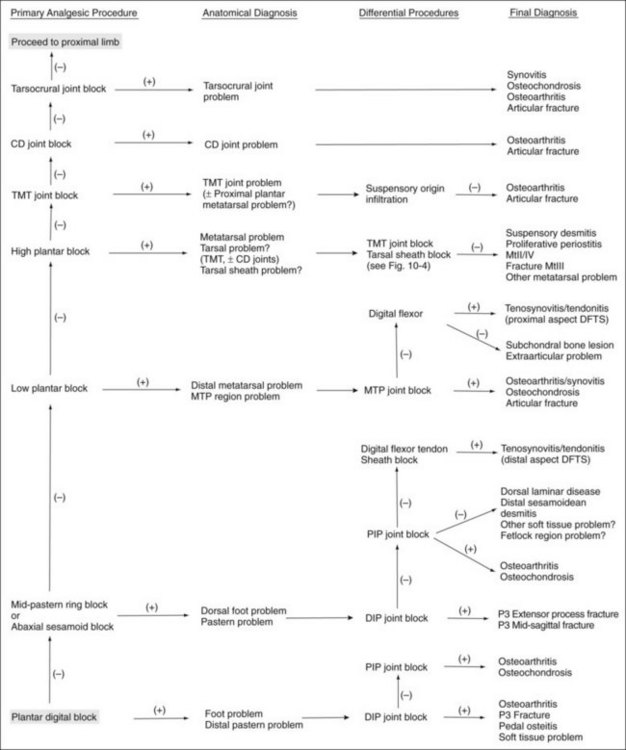

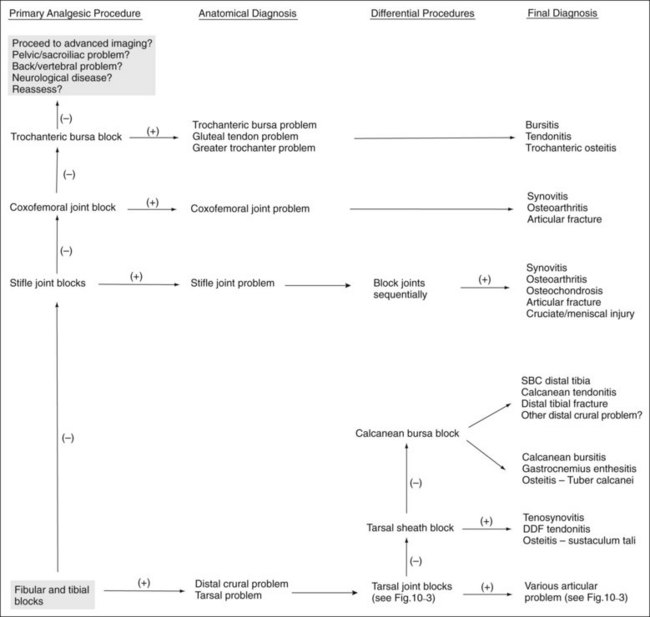

A few basic principles must be followed to ensure success. A thorough working knowledge of regional anatomy is required. Even for seasoned veterans a review of anatomy may be required before less common techniques are performed. A most important principle when performing perineural analgesia is to start distally in the limb and work proximally (Figures 10-1 to 10-4). If possible, sequential blocks from distal to proximal should always be used, but in certain circumstances a different strategy can be successful. Sequential blocking requires a fair amount of time, and in certain horses, selective intraarticular or local blocks can be performed without following this “golden rule.” However, in most situations, blocking a large portion of the distal limb at a proximally located site may preclude accurate determination of the source of pain causing lameness and may require an additional visit to perform additional diagnostic procedures.

During this portion of the examination, we are attempting to eliminate baseline rather than induced lameness, and care must be taken when adopting the practice of “blocking out a positive flexion test” (see Chapter 8). Once baseline lameness has been eliminated, we rarely perform additional flexion tests or attempt to eliminate all induced lameness.

Injection Techniques

Perineural injections are typically performed using needles ranging in size from 25 gauge, 1.6 cm ( inch) to 20 gauge, 2.5 or 4 cm (1 to

inch) to 20 gauge, 2.5 or 4 cm (1 to  inches). Small needles cause less pain but carry the risk of breaking off within tissues if the horse kicks out or otherwise misbehaves. For this reason, we recommend using 18- or 19-gauge needles for injections or blocks within the proximal metatarsal or plantar tarsal regions. In the distal aspect of the limb the needle is inserted subcutaneously directly over and parallel to the nerve. We generally direct the needle proximally rather than distally, although this portion of the procedure differs among clinicians. One of the Editors (SJD) always inserts the needle distally; if a fractious horse throws the limb to the ground the needle is more likely to stay in situ, and the remainder of the procedure may be completed with the limb on the ground. Directing the needle distally also ensures more distal placement of the local anesthetic solution, which may be important at distal sites. The needle is inserted before the syringe is attached. To avoid excessive manipulation once the needle is inserted, a slip-type syringe hub is preferred. Syringes with screw-on hubs can be difficult to attach, requiring additional manipulation in a sometimes fractious horse, and are not generally used. However, when dense tissue requires that additional force be used for injection, the seal between the hub and the needle can be broken, a complication minimized by using a screw-on hub (see the following discussion of lateral palmar block).

inches). Small needles cause less pain but carry the risk of breaking off within tissues if the horse kicks out or otherwise misbehaves. For this reason, we recommend using 18- or 19-gauge needles for injections or blocks within the proximal metatarsal or plantar tarsal regions. In the distal aspect of the limb the needle is inserted subcutaneously directly over and parallel to the nerve. We generally direct the needle proximally rather than distally, although this portion of the procedure differs among clinicians. One of the Editors (SJD) always inserts the needle distally; if a fractious horse throws the limb to the ground the needle is more likely to stay in situ, and the remainder of the procedure may be completed with the limb on the ground. Directing the needle distally also ensures more distal placement of the local anesthetic solution, which may be important at distal sites. The needle is inserted before the syringe is attached. To avoid excessive manipulation once the needle is inserted, a slip-type syringe hub is preferred. Syringes with screw-on hubs can be difficult to attach, requiring additional manipulation in a sometimes fractious horse, and are not generally used. However, when dense tissue requires that additional force be used for injection, the seal between the hub and the needle can be broken, a complication minimized by using a screw-on hub (see the following discussion of lateral palmar block).

Perineural Analgesia in the Forelimb

Palmar Digital Analgesia

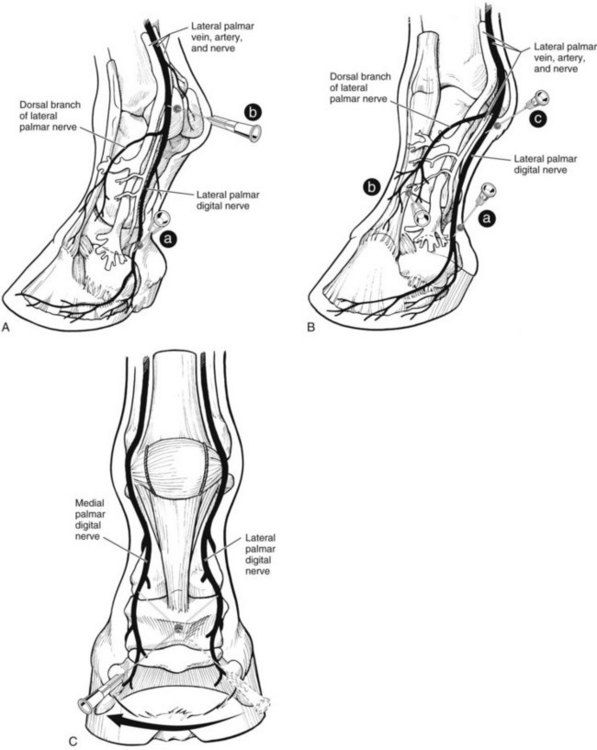

A 25-gauge, 1.6-cm needle is inserted subcutaneously, directly over the nerve, just proximal to the cartilages of the foot (Figure 10-5). One of us (LHB) directs the needle in a distal direction, whereas the other (MWR) directs the needle in a proximal direction to avoid deeper penetration or laceration of digital vessels if the horse withdraws the limb. Alternatively, a 22-gauge, 4-cm needle can be inserted on the palmar midline in the midpastern region, and local anesthetic solution is then infiltrated in a V-shaped pattern. This modification of the palmar digital block is quite difficult to perform in the hindlimb but when done in the forelimb provides maximal analgesia to the bulbs of the heel and minimizes the potential for depositing local anesthetic solution dorsal to the nerve. Loss of skin sensation in the midline between the bulbs of the heels should be assessed, because this area seems most recalcitrant to palmar digital analgesia. Deep pain is assessed using hoof testers. However, if skin sensation persists, it is still worth reevaluating lameness, because in some horses deep pain and lameness may be abolished despite the persistence of skin sensation.

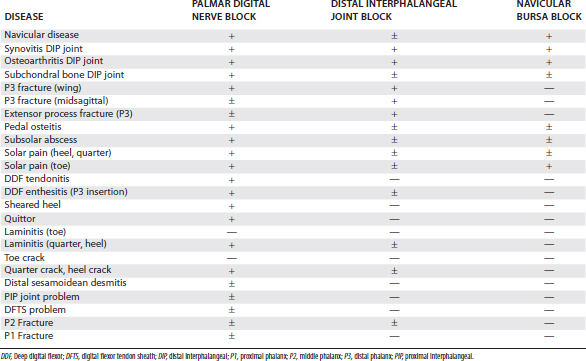

Classically, most horses that responded positively to palmar digital analgesia were thought to have navicular syndrome, but this block desensitizes many lameness conditions within and outside the hoof capsule (Table 10-1). This is an important and common misconception. Lameness in horses with proximal interphalangeal joint pain, midsagittal fracture of the proximal phalanx, or other conditions involving the fetlock joints can be abolished using palmar digital analgesia.7,23 Although using small volumes of local anesthetic solution and performing the block just above the cartilages of the foot may help to minimize the area of analgesia, these procedures do not prevent inadvertent diagnosis in some horses. Diffusion of local anesthetic solution is the most likely explanation, and even a small volume can readily spread in a proximal direction, but the normal anatomy of the digit prevents distal placement of local anesthetic solution (Figure 10-6).

Midpastern Ring Block

A 20- to 22-gauge, 4-cm needle is used to deposit subcutaneously 10 to 12 mL of local anesthetic solution, beginning near the injection site used for palmar digital analgesia over the lateral neurovascular bundle and continuing dorsally and medially, ending over the medial neurovascular bundle (see Figure 10-5). Resistance to needle advancement and injection of local anesthetic solution will invariably be encountered dorsally, if the block is done just proximal to the coronary band, because of the dense tissue (proximal interphalangeal joint capsule, extensor branches of the suspensory ligament, and extensor tendons). Performing the block in the midpastern region minimizes this problem and mitigates the potential for inadvertent penetration of the proximal interphalangeal joint.

Low Palmar Analgesia

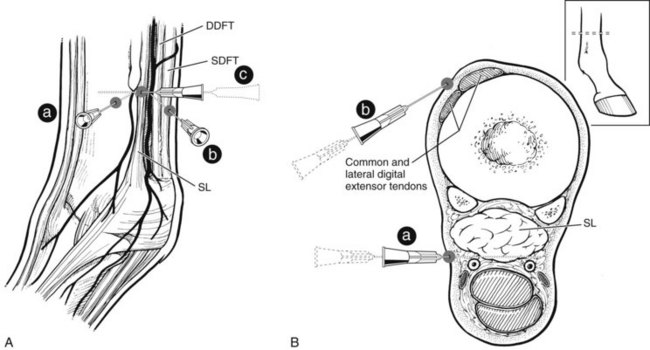

The low palmar block is performed at the level of the distal end (bell or button) of the second and fourth metacarpal bones (splint bones), with the limb in a standing position or held off the ground (Figure 10-7). A 20- or 22-gauge needle is used to inject 1.5 to 5 mL of local anesthetic solution at each injection site. To block the palmar metacarpal nerves, the needle is inserted perpendicular to the skin, just distal to the end of the splint bones, to a depth of 1 to 2 cm. It is important to deposit local anesthetic solution deep in the injection site, rather than simply in a subcutaneous location. While local anesthetic solution is continuously injected, the needle is slowly withdrawn, leaving a visible bleb in the subcutaneous space. To block the medial and lateral palmar nerves, the needle is inserted subcutaneously, in the palmar aspect of the space between the suspensory ligament and DDFT at the level of or slightly more proximal to the distal end of the splint bone. To improve the accuracy of the injection, using a fan-shaped injection technique is helpful. If the digital flexor tendon sheath (DFTS) is distended, the injections must be performed more proximally. Inadvertent penetration of the DFTS is possible even if it is not distended, so careful skin preparation is mandatory. To complete this block, local anesthetic solution is placed in the subcutaneous tissues from the bleb at the distal end of the splint bone to the dorsal midline. One of the Editors (SJD) does not do this last step.

Alternatively, some clinicians prefer to use a longer needle first to deposit local anesthetic solution over the palmar metacarpal (metatarsal) nerves. The needle is then pushed subcutaneously to deposit local anesthetic solution over the palmar nerves (see Figure 10-7). When this modification is performed, incompletely blocking the palmar metacarpal (metatarsal) nerves or lacerating the digital vessels is possible. The lateral and medial palmar nerves can be blocked using only the lateral injection site by advancing the needle in a medial direction, palmar to the DDFT. Although each of these modifications may theoretically decrease the number of injections needed to perform this technique, they have the disadvantages of potential hemorrhage and incomplete analgesia.

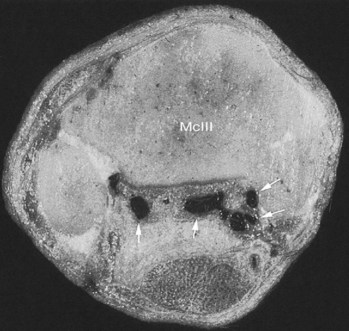

High Palmar Block

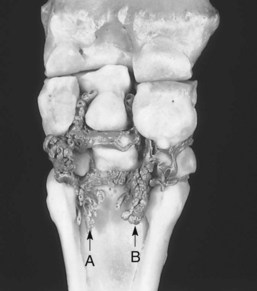

To provide analgesia to the metacarpal region, the high palmar block (high four-point, subcarpal block) is the most common technique, but a modified block (lateral palmar or Wheat block) can be performed. Inadvertent penetration of the carpometacarpal joint is a potential complication with the high palmar block. A similar complication can occur in the hindlimb but is less frequent (see the following discussion). Inadvertent penetration of the carpometacarpal joint occurred in 17% of specimens, in which a conventional high palmar block was performed, because of extensive distopalmar outpouchings (Figures 10-8 and 10-9). However, when the high palmar block was performed within 2.5 cm of the carpometacarpal joint, inadvertent penetration of this joint occurred in 67% of specimens. The carpometacarpal joint always communicates with the middle carpal joint, and therefore penetration of the carpometacarpal joint during high palmar analgesia would lead the clinician to diagnose a metacarpal problem, when in reality the authentic lameness condition exists in the carpus. Moving the injection site in a distal direction decreases the possibility of entering the carpometacarpal joint but also narrows the scope of the technique and may result in a false-negative response in a horse with proximal suspensory desmitis. Two ways around this likely complication are these: first, the clinician could perform middle carpal analgesia before performing high palmar analgesia; second, the clinician could perform a lateral palmar block in lieu of the conventional high palmar technique. In an experimental study, the carpal joints were unlikely to be entered inadvertently during performance of the lateral palmar block, although in every specimen, local anesthetic solution would have entered the carpal canal.25 Unless the clinician is familiar with the lateral palmar block, the most straightforward approach to reduce the possibility of misdiagnosis in this region is to perform middle carpal analgesia before proceeding to the high palmar block. When local anesthetic solution is placed in the middle carpal joint, not only is the carpometacarpal joint blocked, but also the possibility exists of providing local analgesia to the proximal palmar metacarpal region. With this approach, abolishing pain associated with proximal suspensory attachment avulsion injury (desmitis, fracture), stress remodeling, and longitudinal fracture is possible (see Chapter 37). The palmar metacarpal nerves and suspensory branches from the lateral palmar nerve are closely associated with the distopalmar outpouchings of the carpometacarpal joint, and diffusion of local anesthetic solution from this area could explain in part this clinical finding (Figure 10-10).

It is important for the clinician to understand that interpretation of analgesic techniques in the proximal palmar metacarpal region or carpus can be somewhat complex. Correct diagnosis is always the key, and comprehensive evaluation using multiple imaging modalities is a must in differentiating lameness in this region. From the clinical perspective, one is more likely to assume incorrectly that one is dealing with a carpal problem when the authentic lameness condition resides in the proximal palmar metacarpal region than vice versa. Numerous techniques are used to perform high palmar analgesia; some provide partial and others provide complete analgesia to the metacarpal region. For complete analgesia, blocking the following nerves is necessary: the medial and lateral palmar nerves, the medial and lateral palmar metacarpal nerves, the suspensory branches, and nerves providing skin sensation along the dorsum (dorsal branch of ulnar nerve and musculocutaneous nerve). To block these nerves effectively, one must use a site close to the carpometacarpal joint, at the level where the splint bones begin to taper (Figure 10-11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

to 3 hours and 2 to 3 hours, respectively. In contrast, bupivacaine is intermediate in onset but has a much longer duration of action (3 to 6 hours).4 Bupivacaine is most suited for providing therapeutic rather than diagnostic analgesia. The results in clinical practice vary, because in severely lame horses the degree and duration of local analgesia are decreased, regardless of the agent used.

to 3 hours and 2 to 3 hours, respectively. In contrast, bupivacaine is intermediate in onset but has a much longer duration of action (3 to 6 hours).4 Bupivacaine is most suited for providing therapeutic rather than diagnostic analgesia. The results in clinical practice vary, because in severely lame horses the degree and duration of local analgesia are decreased, regardless of the agent used.