CHAPTER 11Diagnosis of Oviductal Disorders and Diagnostic Techniques

Diagnosis of disorders involving the oviduct, along with associated fimbrial and ovarian disorders, should be one of the last procedures employed to diagnose infertility in the mare. However, these isolated reproductive disorders may deserve attention in a select group of barren mares that defy routine explanation for infertility.

Evaluation of the reproductive tract of the mare should involve a thorough evaluation of reproductive history, transrectal palpation, ultrasonography, endometrial culture, endometrial biopsy, cytologic examination, hormonal evaluation, and hysteroscopy before considering oviductal infertility. Diagnosis of infertility due to oviductal disorders should be considered when all avenues of evaluation have failed to provide a definitive diagnosis in cases of barren mares that have had sophisticated veterinary management. In these cases, early detection of pregnancy via ultrasonography or embryo flushing has failed to demonstrate evidence of conception. Oviduct disorders are more prevalent in older mares.1,2,3 A mean age of 18 years has been reported, with a range of 9 to 26 years of age.3

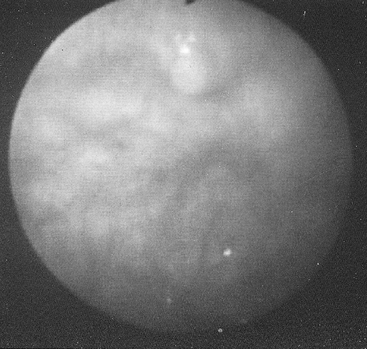

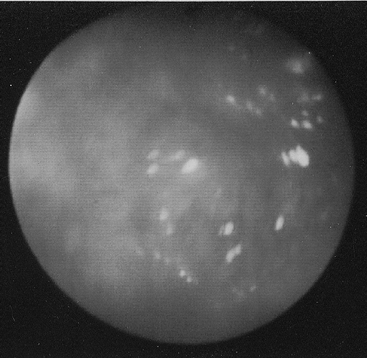

Hysteroscopic evaluation of the uterus and evaluation of the uterotubal junction (UTJ) is of primary importance. The normal UTJ will project slightly into the insufflated uterine horn, giving a papilla type of appearance (i.e., pimplelike). The area around the UTJ should be examined for cysts, adhesions, fibrosis, or any other uterine abnormality that may cause obstruction of the UTJ. Many of these issues can be addressed endoscopically with the use of the Nd:YAG laser4 (Surgical Laser Technologies Inc., Oaks, Pa.) or treated via uterotomy during an exploratory reproductive surgery. Flattening and/or scarring of the UTJ papillae is also considered an abnormal finding warranting further oviduct evaluation (Figures 11-1 and 11-2). The inability to visualize the papillae hysteroscopically is also an abnormal finding.

Catheterization of the equine oviduct through the UTJ papillae from the uterine lumen is technically an extremely difficult procedure, unlike other mammalian species. This is because the equine oviduct is anatomically distinct from other mammalian species. The distal one third of the equine oviduct has a well-developed muscularis, which acts as a sphincter apparatus, making mechanical entry from the uterus exceedingly difficult.5 The distal one third of the oviduct is also extremely convoluted, which further complicates catheterization from the uterine approach. Maintaining catheter placement from the uterine approach is also tenuous, because the muscularis-induced back-pressure that occurs during oviduct irrigation invariably ejects the catheter from the oviduct. Balloon catheterization of the oviduct from the uterine approach is not possible with current technology. Again, because of the well-developed distal oviduct muscularis, balloon insufflation is prevented within the distal one third of the oviduct (Figure 11-3).

Oviductal masses and occlusions of the lumen of the oviduct with a collagen type of material has been described1,6,7 and has a prevalence in older mares.1,2 The mare frequently retains oocytes in various stages of degeneration within the oviductal lumen.1,2,5,6,8–10 It is not known at this time if these oviductal collagen type of masses and degenerated oocytes are interrelated or separate entities, and more research is needed. Due to the oviductal muscular sphincter apparatus, transport of collagen type of masses to the UTJ is thought to be difficult, thus occluding the oviductal lumen or interfering with proper oviductal function.1,7,8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree