CHAPTER 17 Diagnosis and Treatment of Low-Grade Alimentary Lymphoma

CLASSIFICATION OF ALIMENTARY LYMPHOMA

Feline lymphoma can be classified broadly according to anatomical location, histological grade, or immunophenotype. The traditional anatomical classification recognizes mediastinal, multicentric, alimentary, and extranodal forms. Alimentary lymphoma is characterized by infiltration of the gastrointestinal tract with neoplastic lymphocytes, with or without mesenteric lymph node involvement.1–3 Feline alimentary lymphoma can be classified according to histological criteria using the National Cancer Institute Working Formulation (NCIWF) into high-grade, intermediate-grade, or low-grade forms (Table 17-1).4–8 Low-grade alimentary lymphoma (LGAL) has been recognized increasingly in cats over the last 10 years.6,9–12 Synonyms of LGAL include well-differentiated, lymphocytic, and small cell alimentary lymphoma. Most LGALs are of the small lymphocytic lymphoma subtype (see Table 17-1).9,10,12 A separate histological subclassification of alimentary lymphoma, that of large granular lymphocytic lymphoma, also is recognized.13,14 The majority of LGAL and large granular lymphocytic lymphomas are of the T-cell immunophenotype, whereas intermediate- or high-grade lymphomas in the gastrointestinal tract typically are of B-cell origin.5–10,13–16 LGAL and high-grade alimentary lymphoma (HGAL) in cats differ markedly in clinical presentation, as well as in techniques required for diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis (Table 17-2). The two forms should be considered as distinct clinical entities.

Table 17-1 Histological Classification of Feline Lymphoproliferative Disease as Applied to Feline Lymphoma or Lymphoid Leukemia7

| Tumor Type | Acronym | |

|---|---|---|

| Low Grade | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | CLL |

| Small lymphocytic lymphoma | SLL | |

| Small lymphocytic intermediate lymphoma | SLLI | |

| Small lymphocytic plasmacytoid/plasmacytoma | SLLP | |

| Follicular small cleaved-cell lymphoma | FSC | |

| Follicular mixed-cell lymphoma | FM | |

| Intermediate Grade | Follicular large-cell lymphoma | FL |

| Small cleaved-cell lymphoma | SCC | |

| Mixed-cell lymphoma | MC | |

| Large-cell lymphoma | LC | |

| Large cleaved-cell lymphoma | LCC | |

| High Grade | Acute lymphocytic leukemia | ALL |

| Immunoblastic lymphoma | IB | |

| Immunoblastic small-cell lymphoma | IBS | |

| Immunoblastic polymorphous lymphoma | IBP | |

| Small noncleaved-cell lymphoma | SNC | |

| Lymphoblastic lymphoma | LB | |

| Lymphoblastic convoluted-cell lymphoma | LBC |

Table 17-2 Comparison of Clinically Relevant Features of High-Grade and Low-Grade Alimentary Lymphoma in Cats

| High Grade | Low Grade | |

|---|---|---|

| Median age at presentation | 12 years | 13 years |

| FeLV antigen status | >70% negative | >99% negative |

| Gross appearance | Usually focal or segmental intestinal involvement | Usually diffuse intestinal involvement |

| Immunophenotype | B cell | T cell |

| Recommended chemotherapy protocol | Multiagent CHOP | Prednisolone and chlorambucil |

| Major route of chemotherapy administration | Intravenous | Oral |

| Complete remission (CR) | 38-87% | 56-76% |

| Median survival time (for cats achieving CR) | 8 months | 19-29 months |

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Alimentary lymphoma is the most common anatomical form of lymphoma in cats identified in most studies.1,17–20 The declining influence of feline leukemia virus (FeLV) worldwide has resulted in an increase in the prevalence of alimentary lymphoma relative to other anatomical forms because alimentary lymphoma has the weakest association with FeLV antigenemia. Some studies suggest that the incidence of lymphoma, particularly alimentary lymphoma, is increasing.19 At one institution, cases of retrovirus-negative lymphoma increased by 78 per cent in the period of 1994 to 2003, when compared to the period of 1984 to 1994.19 This could not be accounted for by the coincident increase in the feline caseload, which was 29 per cent for the same period. However, whether this trend reflects a true increase in the incidence of alimentary lymphoma or an increased demand for further investigation of feline disorders is unclear.

Low-grade lymphomas constitute 10 to 13 per cent of all feline lymphomas.5,7,10 The relative incidence of the different histological subtypes of alimentary lymphoma in the general population is unknown. However, LGAL is common among referral feline populations, comprising 45 per cent and 75 per cent of all cases of alimentary lymphoma.6,12 At our institution, the proportion of alimentary lymphomas that were classified as LGAL increased from 11 per cent in 1999 to 45 per cent in 2008.5,12 We consider the most likely reason for this increase to be a greater awareness of low-grade disease. Another contributing factor could be that the diagnosis of intermediate- or high-grade alimentary lymphoma is often obtained with less invasive diagnostic tests, such as cytological examination of fine-needle aspirates, resulting in less frequent referral.

RISK FACTORS

FeLV, a directly oncogenic retrovirus, has a strong association with mediastinal and multicentric T-cell lymphoma in young cats. FeLV antigenemia confers a sixtyfold increased risk for lymphoma development compared to antigen-negative status.21 The ability to detect FeLV provirus may shed more light on the potential role of this virus in lymphomagenesis in exposed but antigen-negative cats.22 Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) infection also increases the risk of lymphomagenesis, but to a lesser degree (fivefold compared to seronegative cats) than that associated with FeLV infection.21 An indirect role is favored for FIV in the development of extranodal B-cell neoplasms.23 There currently is no evidence of a retroviral association with LGAL. Of 76 cats with LGAL tested for FeLV antigen, all were negative, and only one of 77 cats tested for FIV antibody was seropositive.6,9,10,12

It has been suggested that chronic intestinal inflammation is a risk factor for the development of LGAL in cats, but definitive proof is lacking. The phenomenon of inflammation-associated neoplasia is well established and the mechanisms involved are being elucidated.24 Celiac disease in human beings is an inflammatory intestinal disease associated with gluten sensitivity. In genetically predisposed individuals, celiac disease increases the risk of intestinal malignancies, including enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma.25 The histological features of the latter are very similar to those of LGAL in cats, to the extent that some veterinary pathologists refer to LGAL as enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma.11,26 Differentiation of neoplastic from inflammatory populations of lymphocytes in the intestine can be extremely difficult using morphological features alone. Immunophenotyping and clonality testing may be required for a definitive differentiation. It has been proposed that lymphocytic-plasmacytic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) may be a precursor to lymphoid malignancy of the intestinal tract in some cats.* Consistent with this theory, concurrent lymphocytic-plasmacytic IBD has been identified in other regions of the alimentary tract in up to 20 per cent of cats with LGAL.9,12 There are other examples of the apparent progression of chronic inflammation to neoplasia in cats, including injection-associated sarcomas and posttraumatic ocular sarcomas (see Chapter 70), suggesting that this species may be predisposed to inflammation-associated neoplasia.28,29

SIGNALMENT

LGAL typically affects middle-aged to older domestic crossbred cats. The median age at diagnosis is 13 years, with a range of 5 to 18 years. No breed or gender predilection has been identified.6,9,10,12

HISTORY AND CLINICAL SIGNS

The most common clinical signs in cats with LGAL are weight loss (⩾ 80 per cent), vomiting (⩾ 70 per cent), diarrhea (⩾ 60 per cent), and partial or complete anorexia (⩾ 50 per cent). In our experience, the diarrhea usually is small bowel in origin. The patient’s appetite may be normal, although polyphagia is noted occasionally. Less frequently reported signs include lethargy and polydipsia.6,9,10,12,30 In the majority of cases, clinical signs are chronic (i.e., present for more than one month).9,12,30 Abdominal palpation is clinically useful because it is often abnormal in cats with LGAL. Diffusely thickened intestinal loops are detected in one third to more than one half of affected cats (Figure 17-1). An abdominal mass is palpable in 20 to 30 per cent of cases, attributable to either mesenteric lymph node enlargement or, less commonly, to a focal intestinal mass.6,9,12 Because abdominal palpation can be unremarkable in cats with LGAL, the diagnosis can not be excluded on the basis of normal findings during palpation alone.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The presenting signs of LGAL are common to many primary and secondary gastrointestinal diseases. Inflammatory bowel disease is a major differential diagnosis. In one study comparing cats with IBD and LGAL, there was no correlation between the clinical findings and the final diagnosis.30 In older cats with chronic weight loss, vomiting, and/or diarrhea, the exclusion of secondary gastrointestinal diseases can be accomplished by performance of a complete blood count (CBC), biochemistry profile, urinalysis, thoracic radiographs, total serum thyroxine concentration, and retrovirus testing. Measurement of serum trypsin-like immunoreactivity (TLI) and feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (fPLI; now measured as Spec fPL) also may be indicated.

Primary gastrointestinal disorders that may cause this constellation of clinical signs are listed in Box 17-1. Tests for intestinal parasitism should include direct fecal microscopy and zinc sulfate centrifugation flotation. Fecal immunoassays, direct fluorescent antigen tests, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based assays facilitate the detection of Giardia spp., Cryptosporidium spp., Campylobacter spp., and enteropathogenic bacterial toxins. Even when test results are negative, routine treatment for endoparasites with fenbendazole is warranted early during the investigation. For cats with mixed or large bowel diarrhea, further testing for Tritrichomonas foetus by fecal smear examination, culture, or PCR is warranted.31 In cats with bloody diarrhea, especially if accompanied by pyrexia and hematological findings consistent with sepsis, fecal culture for enteropathogenic bacteria, such as Salmonella spp., Clostridium spp., and Campylobacter spp., should be considered. The results should be interpreted with caution because of high carriage rates of these organisms in healthy cats.32 (See Chapters 5 and 15 in the fifth volume of this series for further discussion of these tests.) Dietary elimination trials, using single novel protein and carbohydrate sources or hydrolyzed protein diets, are an important diagnostic tool for suspected adverse food reactions (see Chapter 8). Serum cobalamin and folate concentrations should be measured in all cats with suspected small intestinal disease (see Chapter 15).

Box 17-1 Primary Gastrointestinal Diseases Associated with Chronic Weight Loss, Vomiting, and/or Diarrhea

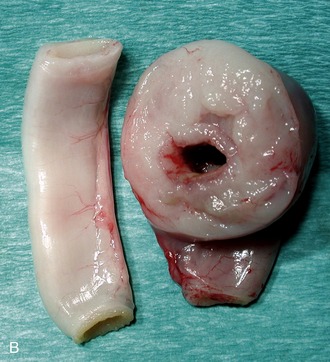

The finding of a palpable intestinal or lymph node mass in an older cat with chronic weight loss, vomiting, and/or diarrhea might suggest HGAL. In these patients, segmental, often eccentric, mural thickening and/or mesenteric lymphadenomegaly is common (Figure 17-2). Epithelial or mast cell neoplasia also should be considered. It is important that LGAL is included on the list of differential diagnoses when an abdominal mass is identified. The latter generally carries a more favorable prognosis with treatment.

DIAGNOSIS

ROUTINE LABORATORY TESTING

Hematological abnormalities in cats with LGAL can include mild anemia from chronic disease or gastrointestinal blood loss, monocytosis, and/or neutrophilic leukocytosis.9,12 On serum biochemistry analysis, hypoalbuminemia may be present, but this occurs less commonly in LGAL (0 to 49 per cent of cases) than with intermediate-grade alimentary lymphoma or HGAL (50 to 75 per cent of cases).6,12,20 Hypoalbuminemia occurs from loss of albumin into the intestinal lumen when the intestinal wall is compromised, but also when the capacity of the liver to synthesize albumin is exceeded. Hypoalbuminemia is less common in cats with LGAL because the integrity of the intestinal wall usually can be maintained until late in the disease process. Increases of serum liver enzyme activities also can occur and may indicate concurrent hepatic involvement.9,12,30

Up to 80 per cent of cats with LGAL are hypocobalaminemic.10 This finding is not unexpected: cobalamin is absorbed through the ileum, and the ileum and jejunum are the most common sites for LGAL. Additionally, utilization of cobalamin by a proliferating intestinal microflora in the proximal intestine can decrease cobalamin available for absorption.33 (See Chapter 13 in the fifth volume of this series for a discussion on the role of cobalamin in the diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal disease.) Serum folate concentrations may be low, normal, or high in cats with LGAL.9,10 Folate deconjugase (a brush border enzyme) and a carrier protein required for folate absorption are located only in the proximal small intestine. Therefore, low serum folate concentrations occur with proximal small intestinal disease due to reduced mucosal absorption. High serum folate concentrations can occur due to proliferation of the intestinal microflora that synthesizes folate.33 In one study, serum folate concentrations were decreased in 5 per cent and increased in 40 per cent of cats with LGAL.10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree