Chapter 49Diagnosis and Management of Pelvic Fractures in the Thoroughbred Racehorse

Diagnostic Techniques

Clinical Examination

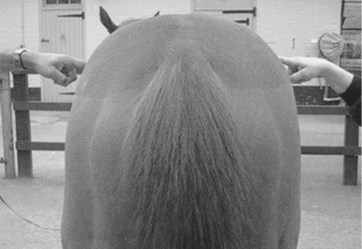

A thorough working knowledge of the anatomy of the equine pelvis is essential for clinical examination to be useful. Because of the large muscle mass over the horse’s hindquarters, only the bony extremities of the pelvis can be palpated. However, it is often possible to gain information about horses with pelvic injuries by studying the position of these bony landmarks. For example, the normal position and angle of the tuber coxae in the racehorse are often disturbed in horses with fracture or sacroiliac joint instability. The position of the tubera coxae can be assessed by viewing the horse from behind, with an assistant placing fingertips on the craniodorsal extremity of the tubera coxae (Figure 49-1). It is important that the horse stands completely level, with both hind feet together, for this test to be meaningful. Some horses, however, show asymmetry viewed in this way that is not linked to lameness. Similarly, careful palpation of the tubera sacrale can give information about the possible involvement of the sacral wing of the ilium or disruption of the sacroiliac joint.

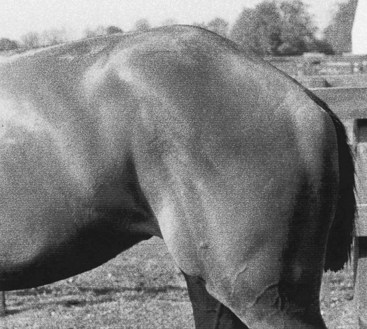

Ventral displacement of one tuber sacrale is commonly encountered in ilial wing fractures, where the overlap of the fracture fragments seems to allow the tuber sacrale to move ventrally. Often a pain response is associated with palpation of a horse with tuber sacrale displacement, and sometimes movement of the bone itself may be felt if the fracture is complete. Fracture of a tuber coxae is often produced by external trauma, usually after a fall, but can also occur as a stress-related athletic injury. This usually results in a cranioventral displacement of the fracture fragment because of the distractive forces of associated musculature. The tuber coxae in these horses can often be felt situated in the sublumbar fossa, and the remnant fracture bed can be palpated at the original site. Fractures of the ischium can sometimes be felt by manual palpation, although the extensive muscle spasm and protective boarding that are associated with these fractures often preclude this examination. Usually there is hemorrhage and swelling in the acute phase, but a clear loss of muscle mass or even a “hollow” in the caudal contour of the rump may develop with time as inflammation subsides. Finally, muscle tone in the tail and anus should be evaluated because fractures involving the sacrum can involve neural elements that supply these structures and cause flaccid paralysis of the tail, rectum, anal ring, and vulva (in a filly), that is, the cauda equina syndrome (Figure 49-2). Bilateral ilial wing fractures can produce the same neurological appearance associated with severe nerve root damage consequent on movement of the pelvis in relation to the sacrum.

Diagnostic Ultrasonography

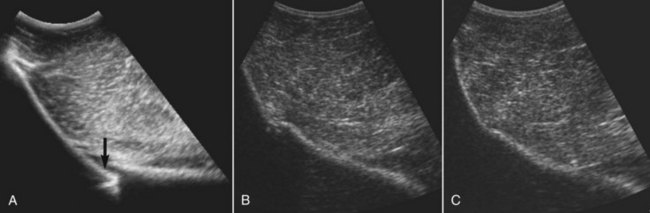

Ultrasonography is useful for diagnosing pelvic fractures and has proved especially useful in demonstrating fractures of the ilial wing (Figure 49-3), ilial shaft, tuber coxae, and ischium. Ultrasonography is quick, easy, and within the capability of clinicians with a suitable ultrasound machine. Ultrasonography may eliminate the requirement for a horse to travel to a referral center for diagnosis, and the risk associated with radiography under general anesthesia can be avoided. Ultrasonography has obvious limitations. For example, adequate imaging of the sacral wing, sacroiliac joint, and the femoral head is not possible. Fractures with minimal displacement or poorly developed callus are also difficult to image, as are incomplete fractures involving the ventral surface of the ilium. For this reason, ultrasonography should not be regarded as a standalone imaging modality for identifying a fracture of the pelvis but should be used with a thorough clinical examination and, if available, scintigraphy. In many horses, the exact site and extent of the fracture can be determined, which allow improved prognostic and management advice to be given. The healing process can be monitored by serial examinations, allowing the management program to be tailored to the individual horse (see Figure 49-3, B and C). A longitudinal- or sector-array ultrasound transducer can be used, provided it has a deep enough penetration to see the bone surface (i.e., a 3.5- or 5-MHz transducer). The muscle mass lying above the bone structures acts as a natural “standoff,” bringing the bone surfaces into the focal zone of the ultrasound beam. A separate standoff may be required to evaluate the position of the tubera sacrale and to detect any displacement. In thin-coated horses, no clipping is required, provided adequate saturation of the coat is achieved by degreasing with a detergent solution (chlorhexidine) or by soaking in surgical spirit, followed by application of a coupling gel before scanning. Horses with thicker hair coats must be clipped to obtain images of adequate quality. Images can be difficult to produce in horses with large amounts of subcutaneous fat because of the attenuating properties of this tissue. Numerous blood vessels running through the musculature can create acoustic shadows, which may be confused with a discontinuity of the bone surface. Identifying the bony landmarks such as the tubera sacrale, tubera coxae, cranial and caudal margins of the ilial wing, and greater trochanters of the femur allow anatomical orientation. A dry pelvic specimen is also useful in orientation. Both sides of the pelvis should be evaluated because the normal side can be used for comparison. However, keep in mind that bilateral ilial wing stress fractures occur and both sides may be abnormal. For recording and reference purposes, the area of the ilial wing imaged is referred to as line A, B, or C, and the distance from the tuber sacrale is measured. Scans aligned longitudinally along the ilial shaft are referred to as line D. This simple system is useful, especially in follow-up examinations. A systematic method for recording ultrasonographic findings has been published elsewhere.8