CHAPTER 9 Developmental Dental Abnormalities

Developmental abnormalities occur commonly in dogs and occasionally in cats. They can be caused by abnormal genetic coding or by damage to developing tissues. The necessity of treatment is based on whether the abnormality negatively impacts the health, function, or comfort of the patient. Radiographic evaluation of the extent of involvement helps the clinician to determine which abnormalities require immediate intervention, which might require treatment or monitoring, and which do not require any intervention at all.

Abnormal Tooth Shape or Structure

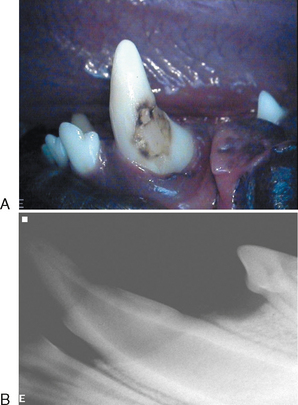

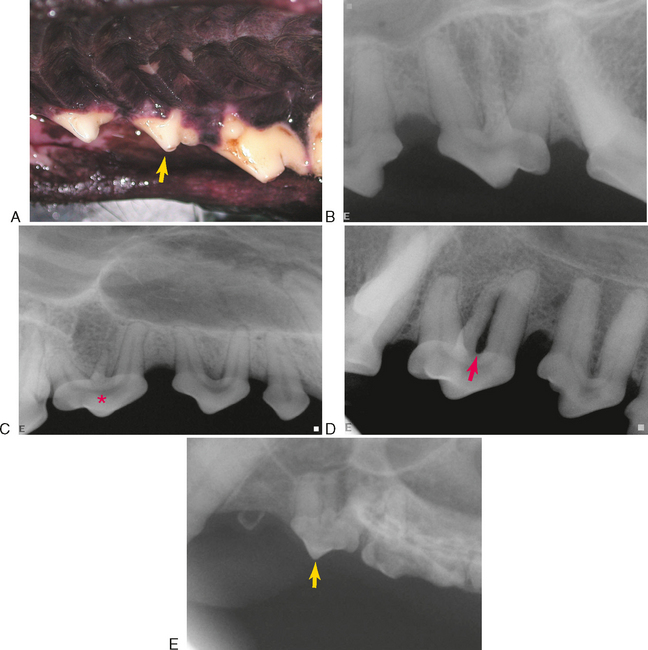

Trauma to a deciduous tooth or inflammation from a fractured deciduous tooth can damage the enamel epithelium of the underlying developing permanent tooth, resulting in a focal area of enamel hypoplasia or hypomineralization (Figure 9-1). This is usually radiographically unremarkable, but a radiograph should be made to evaluate pulp health prior to restoration (Figure 9-2).

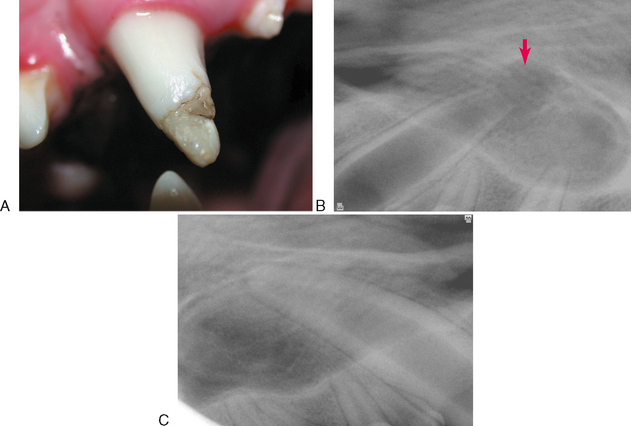

Generalized enamel dysplasia can be caused by systemic diseases (for example, viral infection such as distemper) during development and also by hereditary or nutritional factors. Radiographs should be made to determine whether the tooth root development was also affected (Figures 9-3 and 9-4).

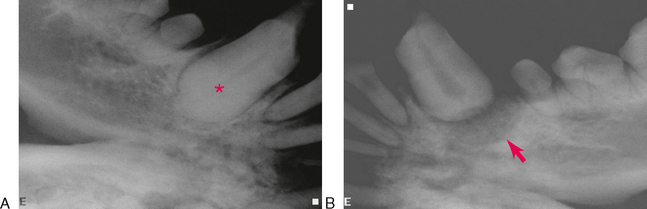

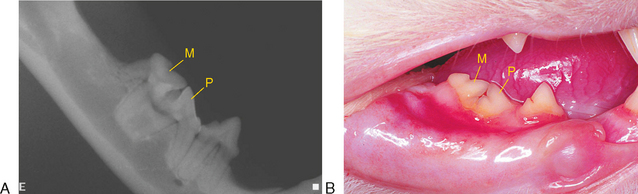

Supernumerary roots most commonly affect maxillary third premolar teeth in both dogs and cats (Figure 9-5). Most are not associated with pathology and may be considered a variation of normal. It can be clinically significant if it is associated with periodontitis, and during extraction or endodontic treatment of the tooth.

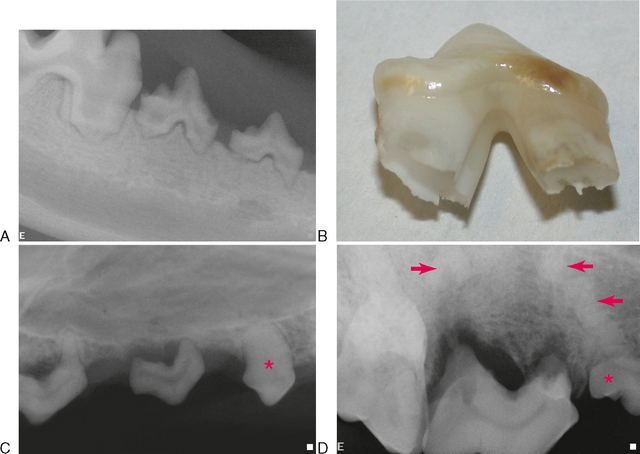

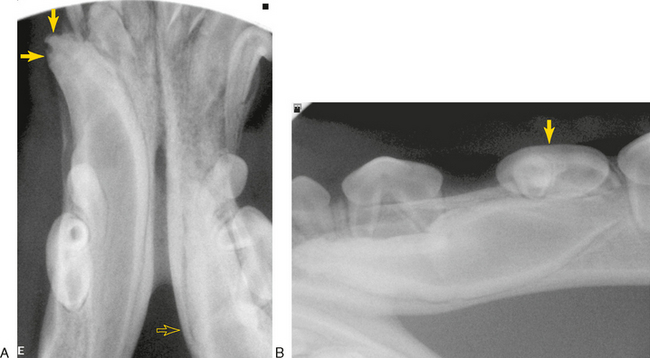

Trauma to a deciduous tooth can also cause dislocation of the underlying permanent tooth bud. When one part of the developing tooth is repositioned relative to other parts, it can result in dilaceration of the tooth, a severe angular defect of the erupting tooth often occurring at the junction of the root to the crown. A deformed tooth may be unable to erupt (Figure 9-6).

Fusion of two tooth germs results in a single large tooth and one fewer tooth in the arch (Figure 9-7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree