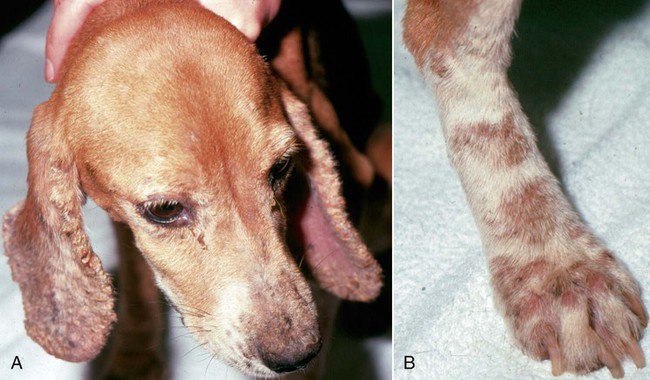

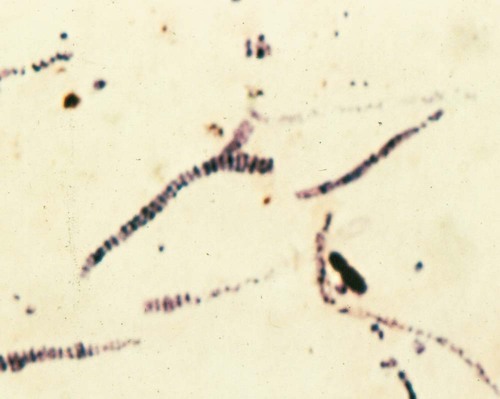

Dermatophilosis (cutaneous streptothricosis) is an exudative skin disease caused by the branching filamentous actinomycete Dermatophilus congolensis. It replicates by hyphalt growth followed by transverse and longitudinal division to produce filaments containing cocci. Dermal crusts that form are composed of alternating layers of keratinocytes, serous vesicles, and neutrophilic infiltrates. When moistened, flagellated cocci are released from the crusts and migrate to new sites on the same or on a different animal. The role of the host immune response in the pathogenesis of this disease has been reviewed.1 Chronic exposure of the skin to trauma or moisture and immunosuppressive therapy or concurrent debilitating diseases may predispose the patient’s skin to overgrowth and colonization by D. congolensis. This aerobe or facultative anaerobe is a normal dermal inhabitant of numerous mammalian species, including horses, sheep, goats, and cattle. Although not primary hosts, cats6,10,13,14 and dogs3,7 can be naturally infected. Acquisition from the soil, contact with another carrier animal, or latent infection in an affected animal cannot be excluded in reported cases. Dermatophilosis has been produced experimentally in dogs after inoculation of the organism onto previously damaged skin15 and in cats by subcutaneous inoculation.10 Trauma associated with insect bites may predispose an animal to or transfer infection. Contamination of puncture wounds is presumed to occur in infected cats. Spontaneous dermatophilosis in dogs is confined to the skin. As a primary dermatologic disease, dermatophilosis produces minimal signs of systemic illness, although emaciation and debilitation may be associated with an underlying immunosuppressive disease process. Lesions in dogs are frequently found on haired portions of the skin and consist of dry, adherent scabs that become entrapped in surrounding hair (Fig. 49-1). Removal of the crusts reveals underlying erythematous and ulcerated skin. In affected cats, deeper abscesses in muscle, lymph nodes, and subcutaneous tissues have been more characteristic. The lesions are submucosal or subcutaneous pyogranulomas that can produce chronic draining fistulas. Fever, anorexia, and regional lymphadenomegaly or abscess formation are common. Ulcerative granulomas in cats that involve the tongue or urinary bladder have also been described.2,14 The simplest and most rapid means of establishing a diagnosis involves removing the dried scabs from epidermal lesions or taking biopsy samples of deeper tissues where abscesses are found. Samples are minced in small amounts of sterile saline or nutrient broth. Some of the material is also used to prepare wet mounts or air-dried smears for microscopic examination, and the remainder is submitted for culture. Wet mounts can be stained with new methylene blue; dried specimens are heat-fixed and best stained by Giemsa methods, although Wright and Gram stains are suitable. Exudates or minced preparations usually contain large numbers of neutrophils in clusters around gram-positive branching filamentous organisms. The filaments are recognized by characteristic transverse and longitudinal divisions that result in three to eight paired rows of coccoid spores arranged linearly (Fig. 49-2). Monoclonal antibodies to D. congolensis have been used with indirect fluorescent antibody staining to specifically identify the organism in clinical samples.9

Dermatophilosis

Etiology and Epidemiology

Clinical Findings

Dogs

Cats

Diagnosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree