CHAPTER 22 Dermatology

Feline Skin Diseases

This chapter focuses on the common skin diseases encountered in clinical practice. Information is arranged in a problem-oriented format. The most commonly encountered feline dermatologic problems are pruritus, scaling and crusting, alopecia, ulcers and erosions, paw and nail disorders, otitis, anal sac diseases, and fragile skin. The chapter concludes with a brief discussion of human allergies to cats. The more uncommon skin diseases of cats are discussed in several excellent encyclopedic sources.40,43,55,66

Diagnostic Approach

The clinic visit is less stressful for all involved parties if the cat is made as comfortable as possible. Some veterinarians prefer to examine cats on clean white towels that have been sprayed with feline pheromones. If the situation allows, the history is obtained first and the carrier is placed on the towel, allowing the cat to relax. The use of prepared diagnostic kits (Figure 22-1) allows specimens to be collected easily once the examination starts. Good lighting and magnification are important because examination of the skin requires close inspection. Handheld magnifying lenses work just as well as magnification examination loops. The amount of light needed for a thorough examination of the skin is similar to that needed for surgery. If high-power spotlights are not available, handheld battery-operated flashlights are an excellent option.

Taking the History

1 Client complaint: This may or may not help determine the dermatologic problem.

1 Date of onset: This helps establish the age of onset and duration of the skin disease.

2 Acute or chronic development: Acute onset may suggest drug reactions or irritant reactions in contrast to a chronic problem that is more compatible with allergic diseases or tumors.

3 Seasonality: Seasonal skin diseases include fleas, flea allergy, atopic dermatitis, and parasitic diseases. Food allergies are not seasonal.

4 What did it look like originally?

5 Is the disease pruritic? This is important and often difficult to establish because many behaviors associated with pruritus in cats may not be recognized as such by owners. When in doubt, the veterinarian should assume that the cat is pruritic.

In cats with known or suspect pruritus, there are five key points to establish:

1 Did the pruritus develop before, at the same time as, or after the lesions developed?

2 How severe is the pruritus, and how frequently does it occur? It is often more helpful to use adjectives rather than a 1-to-10 scale at the initial visit. Terms such as frantic, severe, constant, intermittent, and occasional are more meaningful than a number.

3 How does the pruritus manifest itself (e.g., biting, chewing on nails, hair pulling, rubbing)?

4 Which parts of the body are affected?

5 Does the pruritus respond to treatment with corticosteroids?

Physical Examination

• Whiskers: Are they blunted or broken? This can be sign of pruritus and is common in atopic cats.

• Chin and lips: Is there hair loss? Are comedones or furuncles present? These are signs of facial rubbing.

• Ears and preauricular area: Is there excessive exudate in the ears? What is the consistency? Preauricular hyperpigmentation may be due to inflammation or comedones. Is there evidence of prior auricular hematoma? Are lesions present on the inner pinnae? Is there hair loss or crusting on the pinnae? Dermatophytosis and pemphigus affect the ear pinnae. Are the ear margins normal? Irregular ear margins may be due to trauma, frostbite, or neoplasia. If white hair is present on the head, is the skin normal? If abnormal, this may be due to solar damage, and squamous cell carcinomas or early actinic changes may be evident.

• Nose and face: Hair loss? Crusting? Ulceration?

• Oral cavity: Look for ulcers or erosions.

• Paws and nail beds: Pruritic cats often bite their nails, which will appear as broken and split. Is there black waxy debris near the nail bed or in the interdigital area? This is often a sign of yeast overgrowth associated with allergies or systemic illnesses.77 Pemphigus will cause nail bed exudation and crusting. Are the foot pads normal? Crusting and thickening of the foot pads are abnormal and can be caused by immune-mediated diseases, dermatophytosis, and hepatocutaneous syndrome. Are corns present on the foot pads? This may suggest a disorder of keratinization or a developmental abnormality, or it may explain lameness. Do the foot pads appear puffy? This is common in plasma cell pododermatitis.

• Coat quality: Cats are meticulous groomers, and a matted, unkempt hair coat is abnormal. Is there excessive scaling? Are hairs pierced by scales? This is common in cats with bacterial pyoderma. If scaling is present, is it thick and adherent? This is seriously abnormal and most commonly associated with neoplastic or immune-mediated diseases. It can also be seen in severe dermatophytosis. Do the hairs easily epilate? Is there hair loss? If so, are the hairs blunted, suggesting barbering? What is the overall pattern of hair loss?

• Ventrum: Closely inspect the nipples. Are pustules or crusts present? Pustules around the nipples are rare and most commonly seen in cases of pemphigus. Examine the tail and base of the tail. Excessively oily hair on the tail suggests inflammation of sebaceous glands, poor grooming, or both. Hair loss at the tail base is commonly a sign of pruritus caused by fleas, tapeworms, or both. Closely inspect the skin for primary and secondary lesions. Many lesions are not easily found except by palpation of the skin.

Core Diagnostic Tests

As the examination proceeds, the veterinarian should collect samples at the time a lesion is seen rather than later. This is more efficient and less stressful to the cat. For this reason it is a good idea to keep the dermatology kit (see Figure 22-1) close at hand. Core diagnostic tests include skin scrapings, flea combings, mineral oil ear swab, ear swab cytology, skin cytology (glass slide or tape), hair trichograms, and toothbrush fungal cultures. Box 22-1 contains a list of equipment for in-house dermatologic diagnostic testing.

BOX 22-1 Equipment List for a Dermatology Mini-Laboratory

Frosted glass microscope slides

Skin-scraping spatula (metal weighing spatula used in chemistry labs)

Mineral oil in a dropper bottle

Inexpensive new toothbrushes (unopened)

Sterile culture swabs with transport media

Sterile 25- to 27-gauge needles

20% potassium hydroxide in a dropper bottle

Microscope with 4×, 10×, and oil immersion objectives

Skin Scrapings

The primary parasites identified by skin scrapings are feline Demodex mites, Cheyletiella mites, and Notoedres mites. Otodectes mites can sometimes be found on skin scrapings. Positive skin scrapings rule in a parasite, but negative skin scrapings do not necessarily rule out these parasites. Skin scrapings in cats should only be performed with a skin-scraping spatula (Figure 22-2). Skin-scraping spatulas are safer and less expensive and provide better sample material than dulled scalpel blades. Optimal samples are obtained by putting several drops of mineral oil on the skin and using the length of the spatula (not the tip) to dislodge material from the surface and follicular material by gently scraping with short sweeping movements. Using the length of the spatula allows the veterinarian to gently scrape large or small areas of the skin. The mites of interest are more superficial in the cat’s skin than in the dog’s, so unless there is thickening of the skin, it is rarely necessary to scrape until capillary bleeding is apparent. It is more fruitful to scrape more frequently and over larger areas when dealing with cats with skin disease.

Skin Cytology and Nail Bed Cytology

• Glass slide impression smears: Using a clean glass slide, the veterinarian gently pinches up the skin lesions, making a small fold of target skin, and presses a glass slide firmly over the area. Pressure should be applied directly above the sample site using a thumb or index finger. If this is not done, the slide may break.

• Clear adhesive tape: Using clear adhesive tape, the veterinarian presses the sticky side on the target area and gently pulls up. This is especially useful for small areas of the skin or if the cat is fractious, in which case the owner can be instructed as to where to place the tape. It is critical to skip the fixative step when staining tape cytology specimens because this will damage the tape. Using forceps or clothespins, the tape is dipped is stained and allowed to dry (Figure 22-3). To view the specimen, the veterinarian places a drop of immersion oil on a glass slide and then places the tape over this drop.

• Spatula collection: Using a clean skin-scraping spatula, the veterinarian gently scrapes the skin and smears the material onto a glass slide. This is useful when the target area is small (e.g., focal area of comedones) or when the area is greasy. Nail bed debris or material from between crevices in the skin can be scooped out using a skin-scraping spatula or the wooden end of a cotton swab. This material can then be smeared onto a glass microscope slide.

• Samples collected onto glass slides should be gently heat fixed. This enhances the ability to find yeast. It is important not to heat fix slides if structural architecture is important (e.g., examination of exudate).

Wood’s Lamp Examination

A Wood’s lamp is an ultraviolet light with a wavelength of 273.7 nm filtered through a cobalt or nickel filter. The light interacts with a metabolite on the surface of infected hairs, resulting in an apple-green fluorescence (Figure 22-4). M. canis is the only species of importance in veterinary medicine that fluoresces with a Wood’s lamp. After allowing the lamp to warm up for several minutes, the veterinarian should turn off the room lights and hold the light over suspected lesions for several minutes. The hair examination should continue for at least 3 or 4 minutes to ensure that the examiner’s eyes have adapted to the light. Positive hairs can be plucked for fungal culture or hair trichogram. Not all strains of M. canis fluoresce. Any topical medication can cause a false-positive or false-negative test. The most common false-positive result occurs with the blue-white fluorescence of dust and scales.

Hair Trichograms

Hair trichograms are used to examine hair shafts and hair bulbs for evidence of fungal infections, stage of growth (anagen or telogen), and Demodex mites. Target hairs should be plucked in the direction of growth, placed on a drop of mineral oil, cover slipped, and examined. Mites will be found around the hair bulb. When examining hairs for fungal spores, the veterinarian does not need to use a clearing agent such as potassium hydroxide. Infected hairs will have a cuff of spores around the shaft and appear wider and more filamentous than normal hairs (Figure 22-5). Fungal spores are more refractile. If suspicious glowing hairs cannot be found on a microscope slide, the Wood’s lamp can be used to locate them on the glass slide. The veterinarian should turn out the lights again and hold the lamp over the glass slide to locate them.

Dermatophyte Cultures

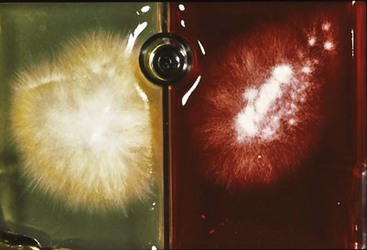

Toothbrush samples are inoculated by gently stabbing the surface of the plate 10 to 20 times with the bristles, taking care not to lift the media off the plate. Commercial media plates should be placed in a self-closing zip-lock bag and labeled. The plastic bag will help minimize cross-contamination of samples, help keep the plate moist, and prevent media mite infestations. Plates are incubated at 21° C to 23.8° C (70° F to 75° F).99 The most commonly used fungal culture media are Dermatophyte Test Media (DTM), which contain a color indicator and plain Sabouraud dextrose agar. It is important to remember that the red color change in the DTM media is only suggestive of, not diagnostic of, a pathogen. Definitive diagnosis requires microscopic examination. If DTM is used, suspect colonies are those that are pale with a red color change surrounding them as they are growing (Figure 22-6). Most pathogens will grow by day 14 of culture. All suspect cultures should be identified microscopically using lactophenol cotton blue stain or new methylene blue stain. A piece of clear acetate tape is pressed to the surface of the growth and placed over a drop of stain. A second drop of stain is placed on top of the tape, and a cover slip is added. Additional information can be found at http://www.doctorfungus.org regarding the identification of common pathogens, particularly M. canis.

Skin Biopsy

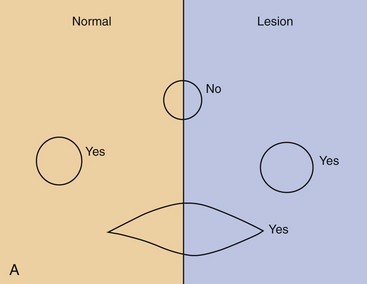

Skin biopsy specimens can be obtained using a scalpel blade or a skin biopsy punch (Figure 22-7). Primary lesions (e.g., pustules, vesicles) should be sampled. If these are not found, several representative samples should be obtained. When multiple skin biopsy specimens are being obtained, lesions should be circled with a black marker so that the veterinarian can identify the sites to biopsy after the local anesthetic has been injected. The skin is not washed or scrubbed because surface pathology is very important in the diagnostic evaluation. A local anesthetic is injected subcutaneously directly beneath the sample. Skin biopsy punches are placed directly over the lesion and twisted in one direction, using gentle pressure; twisting clockwise and counterclockwise produces shear, which ruins the specimen. Because cat skin is very thin, the veterinarian must be careful to cut through to the dermis without penetrating the underlying musculature. Using fine-tipped forceps, the veterinarian harvests the sample by grabbing the subcutaneous fat pedicle; the sample is harvested in the same manner as a flower is plucked (see Figure 22-7, B). If junctional samples are desired, an elliptical biopsy is collected. Blood is gently blotted from the sample, and the subcutaneous side is placed on a piece of tongue depressor and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. If there is a particular lesion or lesions that the clinician wants cut into the block, he or she can place a small black dot on the site and tell the pathologist to section over this site since discriminating features such as erythema can be lost by tissue in fixative. The veterinarian should always include digital pictures and a complete history. The samples should be sent to a laboratory where there are veterinary pathologists with a declared interest in dermatopathology.

Pruritus

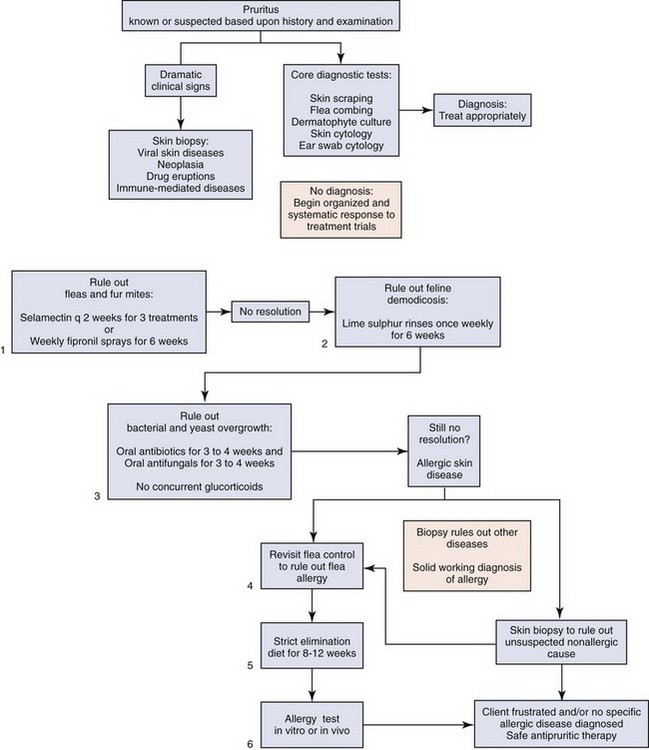

The most common skin problem in cats is pruritus, and the diagnosis either is obvious or requires a systematic work up (Figure 22-8). The three most common causes of pruritus in cats are parasites, infections, and allergic skin diseases. Behaviors and clinical findings associated with pruritus include, but are not limited to, obvious scratching and biting at the body, facial rubbing, broken and bent whiskers, hair loss on the chin, comedone formation on the lips and chin, head shaking, overgrooming in symmetric or asymmetric patterns of hair loss, broken or stubbly hair, salivary staining of the paws, self-mutilation, focal areas of exudation compatible with eosinophilic plaques, twitching, and irritability when petted.

FIGURE 22-8 Pruritus flow chart. Pruritus is known or suspected based on history and examination.

(Image courtesy University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine.)

Parasitic Causes of Pruritus

Otodectes

The most common mite infestation of cats is the ear mite, Otodectes. Ear mites live on or in the ears. Eggs are cemented to the hairs and skin on the margin of the ears. Mites feed on the epithelium, and the ear canal fills with black-brown crumbly material. Kittens are recognized as a high-risk group, but any cat can be affected; adult animals should be examined with the same care as kittens. The classic clinical signs are a coffee-ground discharge and pruritus. Hypersensitivity reactions in cats can develop secondary to mite infestations. Pruritus will be severe, yet mites are often not found. Untreated or inappropriately treated ear mite infestations can lead to secondary infections, purulent otitis externa (OE) or otitis media (OM), and aural hematomas and may be involved in the development of chronic OM in adult cats. Severe mite infestations can occur over the entire body, leading to a pruritic, papular skin disease that can mimic many other parasitic and nonparasitic diseases (Figure 22-9).

FIGURE 22-9 Adult cat with intense otic pruritus due to hypersensitivity reaction to Otodectes.

(Photo courtesy University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine.)

• Debris is gently removed from the ear canal because no topical ear treatments or topical spot-on treatments (e.g., selamectin) can penetrate this material, which can contain a large number of mites and eggs. The mineral oil is useful to soften material.

• Humane relief of ear pruritus is provided by the topical application of an otic steroid.

• A whole-body treatment is used to prevent re-infestation from migrating mites. The concurrent use of an otic miticide and a whole-body flea control product is recommended.

• Treatment of all affected animals (and those with which they are in contact) should be continued for at least 4 weeks.

The application of otic ear mite preparations at night has been recommended on the basis of a report from a human infested with ear mites. This person reported that the mites were more active at night than during the day. In this fascinating report, a veterinarian self-inoculated his ears three times with ear mites.50

Fur Mites and Lice

The most common fur mites of cats include Dermanyssus gallinae, Lynxacarus radovskyi, chiggers (Eutrombicula spp., Walchia americana), and Cheyletiella spp. (see below).40,43,55,66 D. gallinae, or the poultry mite, is most common in wild birds and pet birds. Pet birds can be affected if they are in contact with wild birds. Contact need not be direct; mites can be mechanically transmitted to pet birds through contact with contaminated material or close exposure to nests. Clinical signs vary from none to pruritic papular eruptions. Contact with poultry or exposure to wild birds is an important part of the history. Pet cats are most commonly exposed when homes have wild birds nesting near screened porches. The diagnosis can be difficult, but one helpful finding in the history is if the owner reports finding dead baby birds near these nests.

L. radovskyi infestations have been reported in Hawaii, Texas, and Florida.22 Clinical signs varied from mild to severe pruritus and papular eruption. Mite infestations were generalized and produced large amounts of scale. In the few cases seen by the authors, the mites were not difficult to find.

Treatment options for lice, fur mites, Cheyletiella, and Notoedres infestations are similar. The key to successful treatment is use of a product that is applied to the entire hair coat. If possible, the cat should be bathed to remove debris, excess scales, egg cases, and nits from the hair coat. Nits can be loosened from the hair coat with a 1 : 4 dilution of white household vinegar in water. The solution is applied to the coat for 2 to 3 minutes, and then the hair coat is rinsed. If the cat has long hair and the infestation is severe or if soaking the hair coat is difficult, it may be necessary to clip the coat. These parasites generally have a life cycle of 3 weeks, so a treatment plan of 4 weeks is recommended. Whole-body treatments include lime sulfur rinses, fipronil spray, and pyrethrin sprays.23 Water-based pyrethrin sprays labeled as safe to use in kittens are recommended to minimize the risks of toxicity from pyrethrins. Permethrins are very toxic in cats and should never be used. Whole-body treatments should be done at least once weekly. Concurrent systemic treatment options include ivermectin (0.2 mg/kg to 0.4 mg/kg orally, once daily for 4 weeks) and milbemycin (0.5 to 2 mg/kg orally, once daily for 4 weeks). Selamectin used every 2 weeks for three treatments is also effective; however, it is important to mechanically remove debris, scales, and nits from the hair coat if selamectin is used.

Demodicosis

Demodicosis is increasingly being recognized as a cause of skin disease and pruritus in cats. The disease is caused by D. cati, a long slender mite, or D. gatoi (Figure 22-10), a short, rounded mite. Skin disease may be limited to the ears, causing pruritic otitis. Localized or generalized skin lesions may also be seen. As with dermatophytosis, the clinical presentation is highly variable. Localized lesions are usually characterized by patchy hair loss, scaling, and erythema around the eyes or on the head or neck. Erythema, scales, crusts, easily epilated hairs, symmetric alopecia, or just intense pruritus mimicking feline “hyperesthesia-like” quivering may be all that is found. D. cati is most commonly found in cats with pruritic ears or in cats with skin lesions and concurrent disease such as diabetes mellitus, feline hyperadrenocorticism, feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), feline leukemia virus (FeLV), toxoplasmosis, systemic lupus or other immune-mediated diseases, and neoplasia.70

D. cati is not considered to be a contagious mite. D. gatoi is increasingly being recognized as a pruritic skin disease of cats and is a known contagion; it can be difficult to find on skin scrapings.87 The mite lives in the superficial layers of the stratum corneum, and routine grooming of cats often removes the mite. It is increasingly being found in cats with symmetric alopecia, which suggests that this mite is an overlooked and underdiagnosed cause of this reaction pattern in cats (Figure 22-11).32 Diagnosis is made by demonstration of the mite on skin scrapings, fecal flotation, ear swab cytology, or hair trichogram. In cats with symmetric alopecia, diagnosis is often made by response to treatment.32 D. cati often resolves without treatment if the underlying disease can be identified or managed. It has been successfully treated with lime sulfur rinses every 4 to 7 days for to 8 weeks.23 Feline demodicosis responds well to a number of treatment options, including twice-weekly lime sulfur rinses (e.g., Lime Sulfur Dip, Vet Solutions, Fort Worth, Texas) alone or paired with daily oral ivermectin (200 µg/kg) for 4 to 8 weeks or oral daily milbemycin (0.5 mg/kg) for 4 to 8 weeks. If lime sulfur is not an option, the author (KM) has used topical fipronil spray once weekly. Cats with a suspected or known D. gatoi infestation must be isolated during treatment. All cats in contact with the afflicted cat should be treated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree