CHAPTER 35 Dental and Oral Cavity

Normal Anatomy and Development

Knowledge of the normal deciduous dental formulas and eruption times for the dog and cat will help determine whether pathology exists (Table 35-1 and Box 35-1). The deciduous dentition in the canine and feline contains no molar teeth. In addition to no molar teeth, there is no deciduous counterpart to the first premolar tooth in the dog. Mixed dentition is the term applied to the mouth when both deciduous and permanent teeth are present. This is a normal condition between 4 and 6 months of age.

TABLE 35-1 Approximate eruption times for the deciduous feline and canine dentition

| Tooth | Deciduous dentition (wk) |

|---|---|

| Canine | |

| Incisors | 3-5 |

| Canines | 3-6 |

| Premolars | 4-10 |

| Molars | Not present |

| Feline | |

| Incisors | 2-3 |

| Canines | 3-4 |

| Premolars | 3-6 |

| Molars | Not present |

The number of roots a particular tooth has is important when an extraction is indicated or if a particular tooth has an abnormal number of roots. Often teeth with abnormal numbers of roots or shapes have other structural defects, such as communication through the dentin and pulp to the outside environment. This may lead to endodontic disease. For normal tooth root numbers, see Box 35-2.

Nomenclature

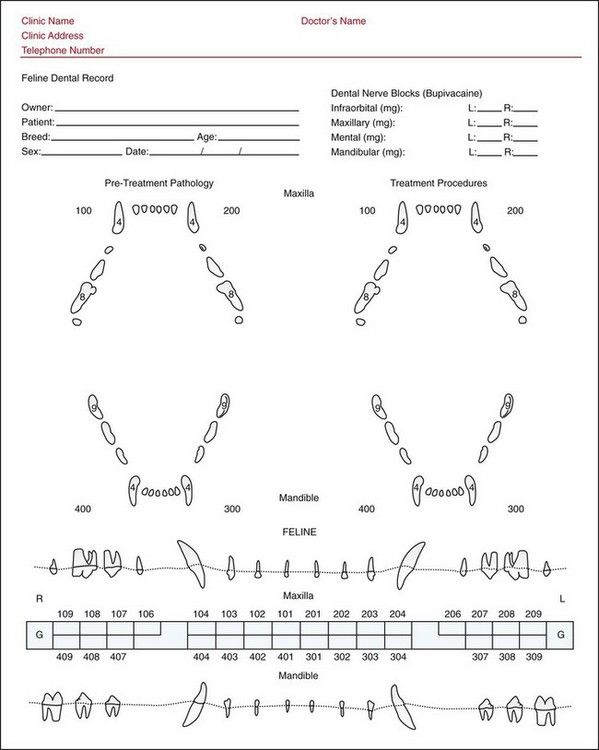

Use of the modified Triadan system of tooth numbering has become common in veterinary nomenclature. A dental chart should be used in the patient’s permanent record to document any abnormalities and subsequent treatment performed. There are numerous charts available from various sources. For the general practitioner, the dental labels made by DentaLabels (Kensington, CA) are useful as they are user friendly and self-adhesive for easy placement in the permanent record. The American Animal Hospital Association provides a very complete dental chart for its members. Most paperless computer programs have dental chart capability as well. See Figures 35-1 and 35-2 for sample dental charts demonstrating the modified Triadan system of tooth numbering.

Figure 35-1 Canine dental record.

(Courtesy Allen Matson, Eastside Veterinary Dentistry, Woodinville, WA.)

Congenital and Hereditary Problems

Persistent Deciduous Teeth

When deciduous teeth exfoliate improperly or incompletely, the deciduous tooth and the permanent tooth are present in the mouth at the same time. No tooth of the same type should be present in the mouth at the same time. If this occurs, the deciduous tooth should be extracted immediately. Persistent deciduous teeth are never normal and should be extracted as soon as a diagnosis is made. Persistent deciduous teeth are also a common cause of malocclusion because they can cause the permanent teeth to erupt in an abnormal location. The permanent premolar teeth generally erupt to the inside (lingually or palatally) of the deciduous counterpart. The exception to this is the upper canine teeth, which erupt in front (mesial) of the deciduous teeth. Figure 35-3 shows an example of a dog with a persistent deciduous left upper canine tooth. The permanent tooth has erupted in an abnormal position because of the failure of the deciduous tooth to exfoliate. This abnormal mesioversion (the tooth is angled toward the front of the mouth) of the canine tooth has also been termed a “lance canine” tooth.

Treatment for persistent deciduous teeth consists of complete extraction of the deciduous tooth. Preoperative intraoral dental radiographs identify location and shape of the tooth to be extracted. A gingival flap may be appropriate to allow adequate visualization and minimize chance of root fracture. Extraction techniques are covered in detail in other texts (see Suggested Reading list); however, it is important to note that deciduous teeth have deceptively long roots compared with crown size, very thin enamel walls, and break easily with overzealous extraction technique (Figure 35-4). It is essential to remove the entire deciduous tooth root when extraction is performed. Incomplete extraction may lead to infection, pain, or malocclusion. Postoperative dental radiographs should be obtained to ensure complete extraction. When performing deciduous tooth extractions, special care should be exercised to avoid trauma to the permanent tooth bud as this can cause damage to the permanent tooth enamel (Figure 35-5).

Missing and Impacted Teeth

Normal tooth eruption occurs in two stages: the intraosseous stage and the supraosseous stage. In the first stage, the overlying bone and the deciduous tooth root (if present) are resorbed. In the second stage, the permanent tooth erupts through the soft tissues. This process can be delayed or interrupted by a number of local and systemic causes, including genetic and congenital problems, trauma, persistent deciduous teeth, thickened fibrous tissue (operculum) covering the unerupted tooth, and failure of bone resorption. It is important to note there are no deciduous precursors to the permanent first premolar teeth in the canine or the molar teeth in both the canine and feline. Knowledge of normal permanent tooth eruption times in addition to dental radiography can differentiate between congenital absence of teeth (oligodontia or anodontia) and impaction. Impaction occurs when a tooth is covered by a tough gingival tissue called the operculum that prevents eruption. When a tooth is embedded, the tooth is not only covered by the operculum but also is covered by bone (Figures 35-6 and 35-7). It is not uncommon to see lower first premolar teeth that are impacted or in an abnormal position, particularly in brachycephalic breeds. Unerupted teeth are prone to developing destructive cystic lesions. These cysts can cause significant damage to the soft and hard tissues surrounding them, including loss of surrounding permanent teeth (Figure 35-8). Because impacted lower first premolar teeth are often in an abnormal position, extraction is usually appropriate.

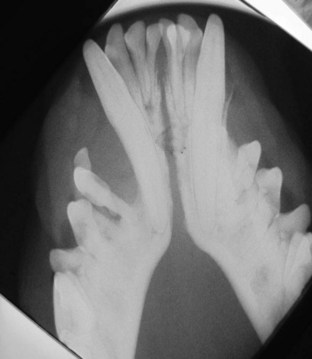

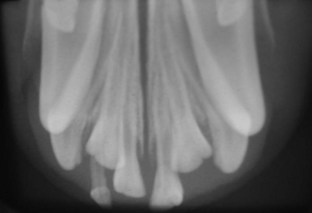

Figure 35-7 Intraoral radiographs of the puppy in Figure 35-6. This radiograph demonstrates that although the teeth are missing clinically, they are present under the gingiva. Left untreated, dentigerous cysts are likely to follow.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree