CHAPTER 4 Cytauxzoon Infections

ETIOLOGY

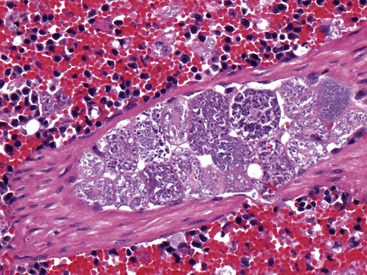

Cytauxzoonosis is caused by the vector-borne hematoprotozoan parasite Cytauxzoon felis. Belonging to the order Piroplasmida, the organism is categorized within the family Theleriidae. Like other Theleriidae, C. felis exists in distinct erythrocytic and nonerythrocytic forms within the mammalian host. The organism undergoes asexual reproduction in the host’s mononuclear phagocytic cells in what is termed the schizont phase of infection. Schizont-laden macrophage cells become distended (Figure 4-1), occluding vasculature to tissues and resulting in the most serious clinical manifestations of disease. Clinical disease appears to be related to the severity of schizogony. Domestic cats typically experience severe schizogony and equally severe clinical illness, while schizogony and clinical illness often are less pronounced in the bobcat reservoir host.1,2

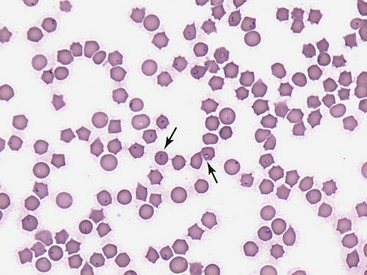

Fission of the schizont within the mononuclear cells results in the formation of merozoites.3 When merozoites are completely formed within the infected mononuclear cells, the distended cells rupture and release merozoites. Red blood cells (RBC) take up merozoites via endocytosis, producing the classic RBC piroplasms associated with infection (Figure 4-2). Piroplasms reproduce through asexual binary fission. The presence of piroplasms sometimes is associated with hemolysis during the later stages of the acute illness. However, the presence of piroplasms is not likely a major contributor to disease. Most felidae that recover from acute infection apparently can harbor the piroplasms for months or even years without serious consequences.4–8 Ingestion of RBC-containing piroplasms serves as the means of transmission of the parasite to the tick intermediate hosts. The tick then will be able to transmit sporozoites to the next felidae on which it feeds.

Although it is the species most relevant to the health of cats in the United States, C. felis is only one of several species of Cytauxzoon protozoal parasites.9 A morphologically indistinguishable intraerythrocytic parasite was found after the importation of Pallas’s cats (Otocolobus manul) from Mongolia.10 Amplification and sequencing of the 18S ribosomal RNA gene from these cats identified a related but separate species, tentatively named C. manul.11 When injected into domestic cats, this pathogen produced erythroparasitemia but no disease, and was unable to prevent virulent disease when those cats were infected subsequently with C. felis.12 Another two similar but distinct pathogens have been detected in Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus) from southern Spain.13 Although the known tick vectors for C. felis are not found in Brazil, cytauxzoonosis has been described in cats from the region; it is unclear if this parasite is genetically identical to the C. felis found in the United States.8,14

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Cytauxzoonosis can occur in cats of any age, although most reported cases have been in young adult cats. Immune suppression is not necessary for cats to become infected, and there is no evidence that infection is more likely in retroviral-infected cats than in healthy cats. No gender or breed predilections have been identified for cytauxzoonosis. Outdoor cats are more likely to acquire this disease, presumably due to an increased exposure to the tick vectors. The greatest risk of infection seems to occur in the spring and summer, presumably during times the tick vector is most active.15 In Oklahoma, peak incidence occurred in May, whereas infections were identified very rarely from November through March.15 Similarly, 75 per cent of clinical cases identified by the University of Missouri Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory over a several-year period were presented between May and July.

For many years after its original description during the mid-1970s in cats from Missouri, cytauxzoonosis was recognized only in states in the south-central United States.16 In recent years, the geographical range of infections has expanded greatly, with infections now reported in cats throughout the southeastern, mid-Atlantic, and south-central United States (Figure 4-3).17,18 Although not yet demonstrated in domestic cats, C. felis infection has been demonstrated in bobcats living as far north as Pennsylvania.19 Because the diagnosis often is based on visualization of RBC inclusions and because necropsy diagnosis of cytauxzoonosis is even more straightforward than antemortem diagnosis, it seems unlikely that infections were simply “missed” in these areas prior to the last decade. Instead, it appears that the infection is now occurring in areas where it did not occur previously.

Because the reservoir host for the pathogen is the bobcat, infected domestic cats typically are from rural or suburban rather than urban areas. Cats living close to wooded areas or less intensely managed land are more likely to become infected.15 It is common for multiple cats in a neighborhood or even a household to become infected within a single season, likely reflecting the presence of infected reservoir hosts in the area.

There are no large published epidemiological studies of C. felis infection in domestic cats. In a single study of healthy cats presented to trap-neuter-return programs in Tennessee (n = 75), Florida (n = 494), and North Carolina (n = 392), prevalence of C. felis as detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) ranged from 1.3 per cent to 0.4 per cent to 0 per cent, respectively.5 It is likely that prevalence rates are higher in regions traditionally found to have enzootic infection; the author is aware of several colonies of cats in Missouri with prevalence rates of up to 45 per cent. Prevalence of infection in cats from Brazil with a hematoprotozoan parasite morphologically indistinguishable from C. felis is similarly high, up to 48.5 per cent.8 Prevalence of infection in bobcats again depends on geography, but estimates range from 7 per cent in Pennsylvania, to 33 per cent in North Carolina, to 62 per cent in Oklahoma.19–21 There are no published studies on incidence of infection. In a retrospective review, cytauxzoonosis accounted for approximately 1 per cent of feline submissions to the Oklahoma Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory, and 1.5 per cent of feline admissions to the Boren Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital between 1995 and 2006 and 1998 and 2006, respectively.15 Personal communications with the author suggest that veterinarians in enzootic “hot spots” see as many as five cases of cytauxzoonosis a week during the peak season, with many more veterinarians in surrounding regions reporting that they see five to 10 cases per summer.

PATHOGENESIS

The most severe manifestations of acute illness associated with cytauxzoonosis appear to be related to the schizogenous phase of infection. In the bobcat reservoir host, schizogony and clinical illness usually are self-limiting.2 On the other hand, infection of domestic cats usually leads to massive schizogony. Mononuclear cells become greatly distended with parasites. These distended cells are found both within the lumen of venous channels and also in the interstitium of most organs; however, parasitemia can be especially severe in the lungs, liver, spleen, and other lymphoid tissues.1,22 Vascular obstruction, anoxia, and release of damaging substances secondary to cell death and rupture all can contribute to multiple organ failure. Less virulent strains of C. felis might result in a more limited schizogony with less associated pathology in domestic cats. The theoretical existence of less virulent strains is supported by a regional occurrence of survivors at a greater than expected rate.4 However, to date there has been no definitive identification of genetically identifiable strains with limited virulence.

Immunity to C. felis is not well understood. It is unclear why bobcats usually develop a more limited schizogenous replication than do domestic cats. We do know that erythroparasitemia acquired via transfusion of piroplasm-containing RBC (rather than erythroparasitemia that follows survival of the acute infection) does not protect domestic cats from subsequent fatal schizogony.23,24 Experimental studies suggest that when domestic cats do survive the schizogenous phase of infection, they become immune to repeated infection and associated clinical illness.24,25 However, the author has spoken with veterinarians in endemic regions who have observed clinical illness indistinguishable from acute cytauxzoonosis in cats known to have survived cytauxzoonosis in previous years. In none of these cats was an attempt made to identify tissue schizonts during the second illness. Therefore it can not be determined if the second illness was caused by reinfection, or if piroplasms were merely the result of infection during the first illness.

TRANSMISSION

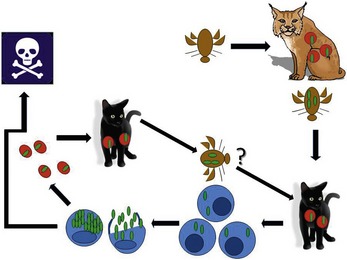

Cytauxzoonosis is a tick-transmitted disease (Figure 4-4). A variety of ticks feed on both domestic and wild felidae, and C. felis has been recovered from both Dermacentor variabilis and Amblyomma americanum species ticks.26 However, vector competence has only been investigated (and confirmed) for D. variabilis.27 Other ticks also can serve as competent vectors for transmission. A parasite morphologically identical to C. felis is described in Brazil, where neither D. variabilis nor A. americanum are reported to occur.8,28

The pathogen C. felis is maintained within the presumed natural reservoir host, the bobcat (Lynx rufus rufus). Unlike domestic cats, when bobcats become infected they undergo a limited schizogony and typically a mild to moderate acute clinical illness (although fatal infection of bobcats has been described).2,23,29 On recovery from illness, bobcats maintain a persistent infection with the RBC piroplasm form of the protozoan for years. Naïve ticks pick up the pathogen after feeding on these persistently infected carriers. If the tick next feeds on another bobcat, the sylvan cycle is repeated. If the tick feeds instead on a domestic cat, infection often results in massive schizogonous replication and profound illness.

Because most domestic cats die from cytauxzoonosis, they have been deemed a terminal host. In the last decade, it has become clear that domestic cats can survive acute illness due to cytauxzoonosis and can remain persistently parasitemic.4,17,30,31 Additionally, domestic cats occasionally are identified who harbor piroplasms without any known history of clinical illness.4,5,8 In an experimental setting, it appears that domestic cats are capable of transmitting infection through the tick vector.32 Whether these carriers harbor an adequate parasite load to make them a reservoir host in a natural setting is unknown. If so, movement of domestic carrier cats (with their owners) might help account for the rapid expansion in the endemic geographical region for this pathogen.

Infection of domestic cats with C. felis in a natural setting requires a tick vector. Co-housing of ill and naïve cats is inadequate to transmit infection.22 Transmission can be accomplished experimentally by inoculation of schizont-laden tissues, or by transfusion of blood (collected during the acute illness) that contains mononuclear cell schizonts.22,23,33 Transfusion of blood from recovered cats, which contains only RBC piroplasms, results in chronic maintenance of the piroplasm stage of infection but does not result in schizogony or clinical illness.23,27

Natural infection has been either confirmed or strongly suspected in a wide variety of felid species, including captive tigers (Panthera tigris), Florida panthers (Felis concolor coryi), Texas cougar (Felis concolor), cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus), and a caracal (Felis caracal).34–39 Extensive experimental transmission studies failed to demonstrate infection of any nonfelidae species, including immunodeficient mice.40

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree