CHAPTER 2 Cutaneous and Subcutaneous Lesions

Masses, Cysts, and Fistulous Tracts

Cytologic examination can be very useful when a cutaneous or subcutaneous lesion is not easily diagnosed by simple clinical evaluation, especially when such lesions are not responsive to therapy. Cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions are easily accessible, and there are no significant contraindications to collecting samples from them. Tranquilization and/or anesthesia is seldom needed for sample collection. Often the cytologic preparation can be collected, prepared, stained, and microscopically evaluated in minutes, providing a diagnosis, prognosis, indication of appropriate therapy, and/or indication of the next diagnostic procedure.

Collection Techniques

Swabs

Generally, cytologic swab smears are collected only when imprints, scrapings, and aspirates cannot be made. Sterile cotton swabs moistened with sterile isotonic fluid, such as 0.9% NaCl, are used. Moistening the swab helps minimize cell damage during sample collection and smear preparation but is unnecessary if the lesion itself is very moist. After sample collection, gently roll the swab along the flat surface of a clean glass slide. Do not rub the swab across the slide surface, since this causes excessive cell damage. If a Romanowsky-type stain is used, air dry the smears before staining (see Chapter 1).

Imprints

Imprints are made by removing any scab covering the lesion and then touching the surface of a clean glass slide to the surface of the lesion. If Dermatophilus congolensis infection is suspected, the underside of the scab is imprinted also. The lesion is then cleaned with a nonirritating antiseptic, wiped dry with a sterile gauze sponge or other clean absorbent material, and reimprinted. High-quality cytologic smears can also be made by imprinting biopsy specimens (see Chapter 1).

Scrapings

Scrapings of cutaneous lesions are made by rubbing the edge of a blunt instrument, such as a glass slide or the back of a scalpel blade, across the lesion. This results in accumulation of cells along the edge of the blunt instrument. These cells are then spread onto a clean, dry glass slide by one of the techniques described in Chapter 1.

Aspirates of Solid Masses

Aspiration Technique: Aspirates are obtained by using a 20- to 25-gauge needle attached to a 3- to 20-ml syringe. If microbiologic evaluation is to be performed on a portion of the sample, the area of aspiration should be surgically prepared. Otherwise, skin preparation is essentially that required for vaccination or venipuncture. An alcohol swab can be used to clean the area.

Hold the mass to be aspirated firmly to aid penetration of the skin and mass and control the direction of the needle. Introduce the needle, attached to a syringe, into the center of the mass and apply strong negative pressure by withdrawing the plunger about one-half to three-fourths the volume of the syringe (see Fig. 1-1). Sample several areas of the mass, but avoid aspiration of the sample into the barrel of the syringe and contamination of the sample by aspiration of tissue surrounding the mass. To accomplish this, when the mass is large enough to allow the needle to be redirected and moved to several areas in the mass without danger of the needle’s leaving the mass, maintain negative pressure during redirection and movement of the needle. However, when the mass is not large enough for the needle to be redirected and moved without danger of the needle leaving the mass, relieve the negative pressure during redirection and movement of the needle. In this situation, apply negative pressure only when the needle is static.

Smears of Aspirates from Solid Masses

A combination of slide preparation techniques can be used to spread aspirates of solid masses (see Figs. 1-2 to 1-5). One combination procedure (see Fig. 1-2) is to spray the aspirate onto the middle of a slide (prep slide). Keeping the prep slide on a flat, solid, horizontal surface, pull another slide (spreader slide) backward at a 45-degree angle to the first slide until it contacts about one third of the aspirate. Then slide the spreader slide forward smoothly and rapidly as if making a blood smear. Next, place the spreader slide horizontally over the back third of the aspirate at a right angle to the prep slide. Use the weight of the top slide to spread the material, resisting the temptation to compress the slides manually. Keeping the top slide flat and horizontal, slide it quickly and smoothly across the prep slide. This makes a squash prep of the back third of the aspirate. The middle third of the aspirate is left untouched.

The squash prep (see Fig. 1-3) is commonly used to spread samples. In expert hands this procedure can yield excellent cytologic smears; however, in less experienced hands it often yields smears that cannot be evaluated because too many cells are ruptured or the sample is not sufficiently spread. Make a squash prep by expelling the aspirate onto the middle of a microscope slide (prep slide). Then place a second slide (spreader slide) over the aspirate at right angles to the first slide. Keeping the spreader slide horizontal with the prep slide, slide the spreader slide rapidly and smoothly across the prep slide. A modification of the squash preparation that has less tendency to rupture cells can be performed by placing the second slide (spreader slide) over the aspirate at right angles to the first slide (prep slide), then rotating the second slide 45 degrees and then lifting it upward (see Fig. 1-4).

Another technique for spreading aspirates (see Fig. 1-5) is to drag the aspirate peripherally in several directions with the point of a needle, producing a starfish-shaped preparation. This technique tends not to damage fragile cells but leaves a thick layer of tissue fluid around the cells. Sometimes the thick layer of fluid prevents individual cells from spreading well, causing them to appear contracted and interfering with evaluation of cell detail. Usually, however, some acceptable areas are present.

General Appearance of Lesion

The general physical appearance of the lesion is helpful in interpreting cytologic findings.

Fistulous Tracts

Fistulous tracts are usually caused by foreign bodies, bone sequestra, or infectious agents. They should be probed for foreign bodies and, if possible, radiographed for sequestra or osteomyelitis. Culture and cytologic swab samples should be collected from deep within the tracts. Cytologic preparations should be carefully perused for filamentous rods staining light blue with intermittent pink to purple dots with Romanowsky-type stains (Plate 3F). This morphology is characteristic of Nocardia spp. and Actinomyces spp., which can cause fistulous tracts, but occasionally occurs with some anaerobic bacteria also, such as Fusobacterium spp.

General Evaluation of Cytologic Smears

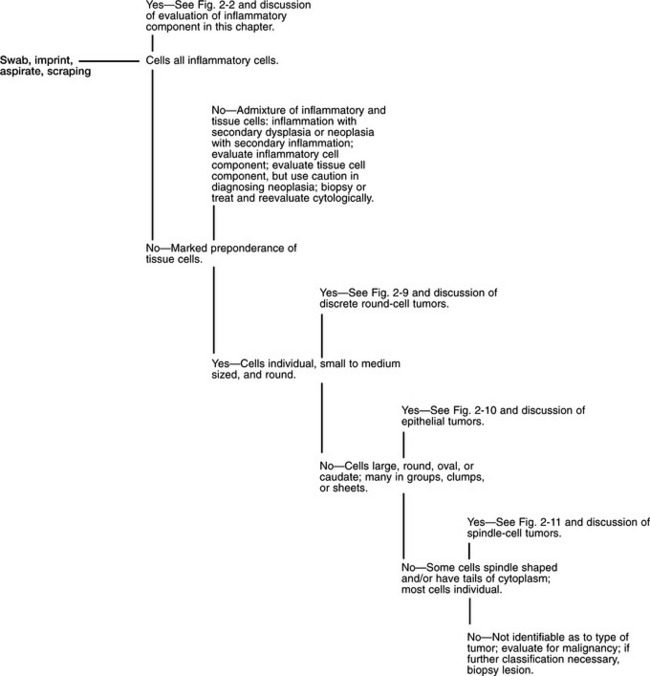

Once a suitable cytologic preparation has been produced, the smears are evaluated for evidence of inflammation and/or neoplasia (Fig. 2-1). If all the cells from a solid mass are tissue cells (ie, no inflammatory cells are present), either the lesion is caused by neoplasia or hyperplasia or the lesion was not sampled and surrounding tissues were sampled. If all the cells are inflammatory cells, an inflammatory process is most likely the primary cause of the lesion, but an inflamed neoplasm cannot be ruled out. An admixture of inflammatory cells and dysplastic tissue cells can be caused by inflammation with secondary tissue-cell dysplasia or neoplasia with secondary inflammation. Therefore, caution must be used in diagnosing neoplasia if evidence of inflammation is detected.

Evaluation of Inflammatory Cell Population

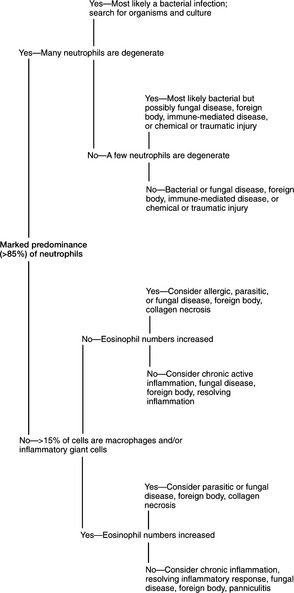

Fig. 2-2 provides an algorithm to aid evaluation of the inflammatory-cell component of cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions. Table 2-1 gives some general considerations for some inflammatory responses. If most of the inflammatory cells are neutrophils (Plates 1A–D, 3A) but no bacteria are found, a covert infection may be present or the neutrophilic inflammatory response may be due to one of the conditions listed under Marked predominance of neutrophils in Table 2-1. The lesion can be cultured to identify a covert infection. If culture results reveal an infectious agent, appropriate therapy can be instituted. If culture results do not reveal an infectious agent or if therapy for the infectious agent identified by culture is not effective, cytologic evaluation can be repeated or a biopsy can be submitted for histopathologic evaluation.

Fig. 2-2 Algorithm to aid in evaluation of aspirates containing preponderance of inflammatory cells.

TABLE 2-1 Some Conditions Suggested by Certain Proportions of Inflammatory Cells

| Inflammatory Cell Population | First Considerations | Second Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Marked Predominance (85%) of Neutrophils | ||

| Many neutrophils degenerate | Gram-negative bacteria Gram-positive bacteria | Abscess secondary to neoplasia, foreign bodies, etc |

| Few degenerate neutrophils | ||

| No degenerate neutrophils | ||

| Admixture of Inflammatory Cells | ||

| 15%-40% macrophages | ||

| >40% macrophages | ||

| Giant inflammatory cells present | ||

| >10% eosinophils | ||

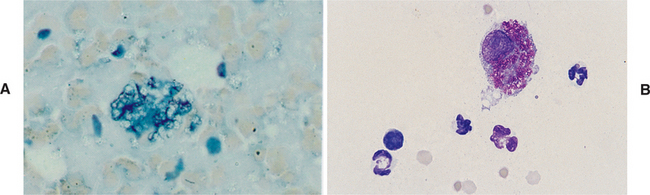

When >15% of the inflammatory cells are macrophages (Plates 2A–D, 3B) and/or giant inflammatory cells are present (Plate 3B), fungal infection or foreign body granuloma should be considered. The slide should be carefully perused for organisms or signs of foreign material, such as refractile debris (Fig. 2-3, A) or eosinophilic material typical of adjuvant (Fig. 2-3, B). Also, historical information concerning possible introduction of foreign material should be sought. If no organisms or foreign materials are found and there is no historical information indicating introduction of a foreign substance into the area, the tissue can be cultured or a biopsy can be submitted for histopathologic examination.

Fig. 2-3 Fine-needle aspirate.

A, Fine-needle aspirate from foreign body reaction. Refractile foreign material is scattered throughout micrograph. Large clump of cell debris and refractile foreign body is in center. (Wright’s stain; original magnification 100X) B, Aspirate from injection site reaction in gelding. Large macrophage contains brightly eosinophilic noncellular material typical of adjuvant. Scattered neutrophils are also present. (Wright’s stain; original magnification 125X)

If the proportion of eosinophils exceeds 10% (Plate 3C), an allergic, parasitic, or foreign body reaction and certain hyphating fungi (eg, phycomycosis) should be considered. Again, the slide should be carefully searched for organisms or signs of foreign material. If none is found, the lesion can be cultured (including fungal cultures) or a biopsy can be submitted for histopathologic evaluation.

When tissue cells showing criteria of malignancy are accompanied by inflammatory cells (Fig. 2-4), the sample should be interpreted cautiously. Dysplasia in tissue cells adjacent to inflammatory reactions can alter tissue cell morphology. As a result, cells undergoing dysplasia in response to a local inflammatory process can be erroneously classified as neoplastic cells. As the intensity of the inflammatory reaction increases, the assurance with which neoplasia can be diagnosed decreases.

Fig. 2-4 Aspirate from nasal polyp caused by Rhinosporidium seeberi.

Note dysplastic epithelial cells (mild anisocytosis, anisokaryosis, prominent nucleoli, coarse chromatin, cytoplasmic basophilia) and numerous neutrophils. Rhinosporidium organisms were found in other areas of smear. (Wright’s stain; original magnification 100X)

Typical Cytologic Characteristics of Selected Infectious Agents

Infectious agents invariably cause lesions containing inflammatory cells. Bacteria usually produce lesions characterized by >85% neutrophils (Plates 1D, 3A) (many of which may be degenerate), a few macrophages, and a few lymphocytes and plasma cells. On the other hand, fungi tend to produce lesions containing more macrophages than in bacterial lesions, but neutrophils often predominate and occasionally eosinophils are plentiful with certain hyphating fungi. Mycotic lesions also often contain lymphocytes, plasma cells, and fibroblasts. The infectious agent, location of the lesion, chronicity of the lesion, and immune status of the animal influence the character of the lesion.

Bacterial Cocci

Most pathogenic bacterial cocci are gram positive and of the genus Staphylococcus or Streptococcus (Plate 3E). Staphylococci usually occur in clusters of 4 to 12 bacteria, while streptococci tend to occur in short or long chains of organisms. When cocci are identified in cytologic preparations and are considered as causing or contributing to the lesion, aerobic and anaerobic cultures and sensitivity tests should be performed to identify the organism and appropriate antibacterial therapy. Because most pathogenic cocci are gram positive, antibacterial therapy effective against gram-positive organisms should be used when it is necessary to initiate therapy before culture and sensitivity results are received.

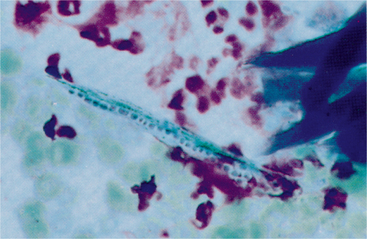

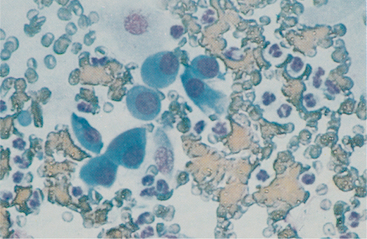

Dermatophilus congolensis: Dermatophilus congolensis is an aerobic to facultatively anaerobic actinomycete that infects the superficial epidermis, causing exudative, crusty lesions. Removal of these crusty lesions reveals eroded to ulcerated skin lesions. Cytologic preparations from the undersurface of scabs from these crusty lesions are most rewarding in demonstrating organisms. These preparations usually contain mature epithelial cells, keratin bars, debris, and organisms. A few neutrophils may also be found. If the undersurface of scabs is dry and does not yield adequate cytologic preparations, crusts and scabs may be minced in saline and smears made for cytologic evaluation. Dermatophilus congolensis replicates by transverse and longitudinal division, producing chains of coccoid cells arranged in two to eight parallel rows. These chains resemble small, blue railroad tracks (Fig. 2-5). Also, many individual coccoid cells may be seen cytologically.

Fig. 2-5 Imprint from underside of scab caused by Dermatophilus congolensis.

There is a background of squamous debris and numerous chains of bacterial doublets. Scattered individual bacteria are also present. (Wright’s stain; original magnification 250X)

Small Bacterial Rods: Most small bacterial rods are gram negative; however, some, such as Corynebacterium spp, are gram positive. Some gram-negative rods can be recognized cytologically as bipolar (Plate 3D). All pathogenic bipolar bacterial rods are gram negative. Rod bacterial infections are usually associated with a marked neutrophilic inflammatory response. When small bacterial rods are recognized in cytologic preparations, the lesion should be cultured to identify the organism and sensitivity tests performed to determine appropriate antibacterial therapy. If it is necessary to institute antibacterial therapy before culture and sensitivity results are received, therapy employed should be effective against gram-negative organisms, since most pathogenic small rods are gram negative.

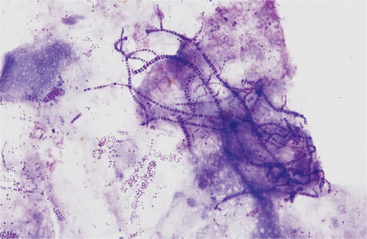

Rarely, the pathogenic filamentous rods of Nocardia spp or Actinomyces spp. (Plate 3F) may cause cutaneous or subcutaneous lesions (abscesses, ulcers, draining tracts, lumps) in horses. These lesions are sometimes referred to as actinomycotic mycetomas. Infection with these agents is uncommon and usually occurs secondary to contamination of existing wounds.1 Also, Mycobacterium spp. and some anaerobes, such as Fusobacterium, rarely may be filamentous. Nocardia and Actinomyces generally have a distinctive morphology in cytologic preparations stained with Romanowsky-type stains. They are characterized by long, slender (filamentous) strands that stain pale blue and have intermittent, small, pink to purple areas (dots). This morphology is characteristic of both Nocardia and Actinomyces spp. and the filamentous form of Fusobacterium spp. When these features are recognized cytologically, cultures should be performed specifically for Nocardia, Actinomyces, and anaerobes.

Mycobacterium spp. (atypical mycobacterial infections and cutaneous tuberculosis), on the other hand, often do not stain with Romanowsky-type stains. As a result, negative images (Plate 4A–B) may be observed in the cytoplasm of macrophages and/or inflammatory giant cells. When epithelioid macrophages and/or inflammatory giant cells are encountered in cytologic preparations not containing any obvious organisms, a careful search for negative images of Mycobacterium spp. should be made. Mycobacterium spp. stain with acid-fast stains. Therefore, when negative images are encountered or when the character of the lesion suggests Mycobacterium spp., an acid-fast stain can be performed to demonstrate the organism and/or cultures for Mycobacterium spp. can be performed to identify the organism.

Sporothrix schenckii: Sporothrix schenckii infection (sporotrichosis) (Plate 4D) most commonly occurs in a cutaneolymphatic form; however, a primary cutaneous form with no lymphatic involvement is seen occasionally. In the cutaneolymphatic form, hard subcutaneous nodules develop along lymphatics and the lymphatics may become corded. The nodules may ulcerate. In horses, the organisms are scarce and cytologic preparations must be perused carefully. If organisms are not found, the lesion should be cultured and a biopsy of the lesion should be submitted for histopathologic evaluation.

In cytologic preparations stained with Romanowsky stains, Sporothrix schenckii organisms are round to oval to fusiform (cigar shaped). They are 3 to 9 μ long and 1 to 3 μ wide and stain pale to medium blue with a slightly eccentric pink to purple nucleus (Plate 4D). They may be confused with Histoplasma capsulatum if only a few organisms are found and the classic fusiform (cigar shape) is not seen.

Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces dermatitidis, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Coccidioides immitis: Cutaneous lesions secondary to infection with Blastomyces, Cryptococcus, Coccidioides, or Histoplasma organisms are rare. These organisms may on rare occasion produce a primary cutaneous lesion or disseminate from other sites and secondarily infect the skin.2–4 Characteristics of these organisms in cytologic preparations stained with Romanowsky-type stains are as follows:

Histoplasma organisms (Plate 4C) are round to slightly oval but are not fusiform or cigar shaped. They are 2 to 4 μ in diameter (about half the size of a RBC), stain pale to medium blue, and contain an eccentric pink to purple nucleus. There is usually a thin, clear halo around the yeast.

Blastomyces dermatitidis organisms are blue, spherical, 8 to 20 μ in diameter, and thick walled (Plates 4E–G). Most organisms are single, but occasionally those showing broad-based budding are found. Imprints of these lesions usually have a cell composition characteristic of pyogranulomatous inflammation (Plate 3B) and few to many organisms.

Cryptococcus neoformans organisms are spherical and usually have a thick mucoid capsule; occasionally, nonencapsulated (rough) forms are found. The organism is 4 to 8 μ in diameter excluding the capsule and 8 to 40 μ in diameter including the capsule. The organism stains light pink to blue-purple and may be slightly granular (Plate 4H). The capsule usually is clear and homogeneous, but it may stain light to medium pink. Cryptococcosis usually evokes a minor granulomatous response of epithelioid macrophages and/or inflammatory giant cells. In some cytologic preparations, Cryptococcus organisms may outnumber inflammatory and tissue cells. Weakly encapsulated (rough) forms tend to elicit a greater inflammatory response than heavily encapsulated forms.

Coccidioides immitis organisms are large (10 to 100 μ in diameter), double-contoured, blue to blue-green spheres with finely granular protoplasm (Plate 5A). Round endospores 2 to 5 μ in diameter may be seen in larger organisms. Cytologic preparations usually have a cell composition characteristic of pyogranulomatous or granulomatous inflammation (Plate 3B). Coccidioides organisms usually are scarce. The tremendous variation in size, presence of endospores, and green tint to the organism differentiate Coccidioides immitis from nonbudding Blastomyces dermatitidis.

Dermatophytes: The dermatophytes Trichophyton spp. and Microsporum spp. cause cutaneous lesions that may have the typical ringworm-like appearance or appear as gray to yellow-brown crusty lesions or as follicular papules.2 Scrapings from the edge of the lesion are most rewarding when searching for dermatophytes. They can be identified in cytologic preparations using the standard 20% potassium hydroxide, in wet mount preparations stained with new methylene blue, or in air-dried preparations stained with Romanowsky-type stains. Cytologically, conidia are found free within the smears as well as within hair shafts (endothrix invasion) or on the hair shaft surface (ectothrix invasion). With Romanowsky-type stains, conidia stain medium to dark blue with a thin clear halo (Fig. 2-6). An inflammatory reaction composed of an admixture of neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells may be seen in cytologic preparations from skin scrapings.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree