Chapter 78Curb

Clinical Appearance of Curb

The convex profile typical of curb is best seen from the side (Figure 78-1). Careful evaluation of swelling from all perspectives, palpation, and thorough lameness examination are critical. Curb must be differentiated from other swellings of the hock, including capped hock, effusion, edema and fibrosis of the calcaneal bursa (see Chapter 79), tarsal tenosynovitis (see Chapter 76), thoroughpin (with or without involvement of the tarsal sheath), and bony enlargements of the distal hock region (see Chapter 44). Injuries of the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) as it courses along the plantaromedial aspect of the hock within the tarsal sheath can produce typical signs of curb, but they account for only a small percentage of injuries in horses with curb.

Horses with sickle-hocked conformation are said to be curby (see Chapter 4). Sickle-hocked and in-at-the-hock conformation lead directly to curb, a finding most common in Standardbred (STB) and Thoroughbred (TB) racehorses. Prognosis for STB racehorses with sickle-hocked conformation and curb is worse in a trotter than in a pacer. Trotters with sickle-hocked conformation are usually fast early in training and racing, but this conformation is often career limiting. Sickle-hocked conformation is also undesirable in TB racehorses. Horses with sickle-hocked conformation often develop curb first, but they then independently or concomitantly develop other lameness associated with the distal hock joints. Tarsal region lameness begins with curb in 2- and 3-year-olds and progresses to osteoarthritis of the centrodistal and tarsometatarsal joints or slab fractures of the central tarsal bone, or more commonly the third tarsal bone.

Horses can have curby conformation without developing curb, and horses with normal hindlimb conformation can develop curb. The proximal aspect of the fourth metatarsal bone (MtIV) is often prominent in horses with sickle-hocked conformation. The most dramatic example of altered joint morphology occurs in young foals with tarsal crush syndrome, the result of delayed or incomplete ossification of the tarsal cuboidal bones (see Chapter 44).

Applied Anatomy and Normal Ultrasonographic Examination of the Plantar Aspect of the Tarsus

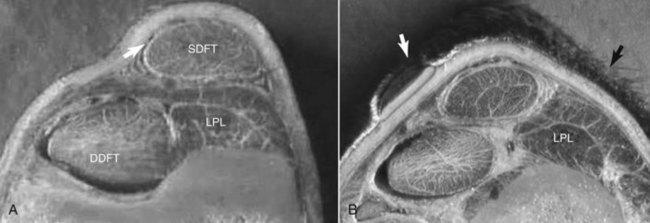

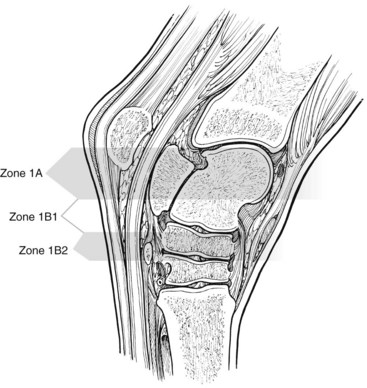

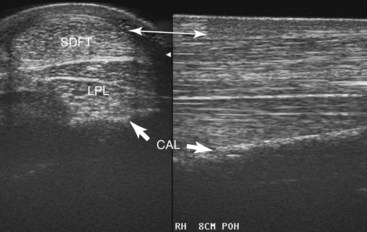

Plantar to the calcaneus are skin, subcutaneous tissues, a thin fibrous tissue layer, the SDFT, and the LPL (Figure 78-2). Medially the DDFT courses distally over the sustentaculum tali, within the tarsal sheath. Normally the tarsal sheath has a small amount of fluid that can be seen during ultrasonographic examination, but it is not felt. The LPL originates from the calcaneus, closely adheres to this bone, and inserts distally on the plantar surface of the fourth tarsal bone and the MtIV. The plantar aspect of the tarsus can be divided into zones to classify findings (Figure 78-3) or the distance measured from the proximal aspect of the calcaneus (point of hock). Swelling comprising curb occurs in zone 1 of the tarsal and metatarsal regions but can extend into zone 2 if SDF tendonitis occurs. Transverse and longitudinal images of both limbs should be obtained from the plantar midline, plantaromedial (to evaluate the DDFT), and slightly plantarolateral (to evaluate the distal aspect of the LPL). Measurement of cross-sectional area (CSA) is important to confirm lesions in which enlargement has occurred but with no overt fiber damage. Precise placement of the ultrasound transducer is important because the LPL changes size and shape as it courses distally. Knowledge of normal ultrasonographic anatomy is crucial (Figures 78-4 to 78-7).3,4