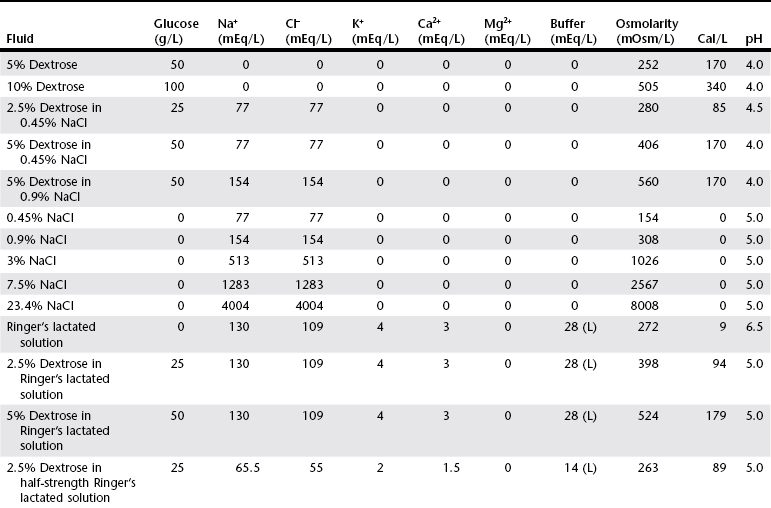

Chapter 1 Crystalloids are classified as isotonic, hypotonic, or hypertonic in relation to plasma osmolality. Isotonic crystalloids are by far the most commonly used fluid type in veterinary medicine (Table 1-1). Also known as replacement fluids, isotonic crystalloids are used to replace fluid deficits that may have developed from excessive loss. The electrolyte composition of isotonic fluid is typically similar to that of plasma. These solutions may also be classified as acidifying (e.g., normal saline) or buffering (e.g., lactated Ringer’s solution [LRS], Normosol-R, Plasma-Lyte 148) solutions. Buffering solutions are considered balanced due to an electrolyte composition that is roughly equal to plasma. Normal saline is not a balanced solution and is acidifying due to a relatively high concentration of chloride and a lack of buffer, both of which decrease plasma bicarbonate. TABLE 1-1 Composition of Commonly Used Fluids* L, Lactate; A, acetate; G, gluconate; B, bicarbonate; Cal, calorie. Hypertonic crystalloids (e.g., 7.5% saline) can be used for short-term, rapid resuscitation and intravascular volume expansion, as well as for treatment of head trauma. These solutions pull water from the interstitium down the concentration gradient into the intravascular space. They are preferred in euhydrated but hypovolemic patients. These fluids cause interstitial and intracellular dehydration and therefore must be followed by administration of isotonic crystalloids. The addition of electrolytes and dextrose may increase the tonicity of isotonic fluids to a hyperosmolar range (see Table 1-1). Hypertonic crystalloids are not intended for long-term use. The term shock dose of fluids has been popularized in emergency and critical care medicine. Twenty years ago it was commonly recommended to give a specific dose of fluids to animals in shock (generally 90 ml/kg in dogs and 60 ml/kg in cats). The volume was set to replace an entire blood volume with crystalloids administered over a period of 1 hour or less. Similarly, administration of shock volumes of fluids was considered the norm in human patients until publication of the landmark study investigating immediate versus delayed fluid resuscitation for hypotensive patients (Bickell et al, 1994). The results of that study challenged the idea that if some fluids are good, more must be better. Multiple experimental studies and clinical trials in people have subsequently demonstrated that excessive crystalloid or synthetic colloid fluid therapy is associated with dilutional coagulopathy, decreased wound healing, increased risk of sepsis, and acute lung injury leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ALI/ARDS). Current resuscitation efforts in massively traumatized humans have focused on treatment with blood and blood products. It is unlikely that most veterinary hospitals have a blood bank with sufficient resources to resuscitate all dogs and cats with blood, but this may become a therapeutic possibility in the future. So what do these studies mean for the clinician treating a patient in hypovolemic shock? Intravascular fluid support is clearly indicated to restore or maintain circulating blood volume. However, the dose of fluid should not be a specific volume but rather a quantity titrated to restore perfusion parameters such as heart rate, mucous membrane color, and peripheral pulse quality to normal values. Blood pressure (BP) is maintained in most cases of shock owing to compensatory mechanisms. Normal BP does not exclude hypovolemia and should be interpreted with caution in patients with other signs of shock. Lactate is a useful surrogate marker of inadequate tissue perfusion, with increased lactate (>2.5 mmol/L) associated most commonly with hypoperfusion. It should be recognized that blood lactate may increase with patient struggling, with excessive muscle activity, in association with metabolic alternations (e.g., neoplasia), and with some medications, most notably prednisone (Boysen et al, 2009). In one small unpublished study of nontraumatic hemoabdomen, dogs randomized to hypertonic saline and hetastarch showed a more rapid time to stabilization than did dogs randomized to crystalloids; however, no differences were noted in either outcome or transfusion needs.*

Crystalloid Fluid Therapy

Types of Crystalloid Fluids

Fluid Management of Hypovolemic Shock

Hypotensive or Low-Volume Resuscitation

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree