CHAPTER 12 Critical Care Nutrition

IMPORTANCE OF NUTRITION DURING CRITICAL ILLNESS

Compared to other animal species, cats have several metabolic adaptations that impact their ability to maintain homeostasis in the face of injury, disease, and food deprivation. For example, cats have a higher requirement for protein and certain amino acids than most other species.1 Critical illness induces further metabolic alterations in cats that put them at even higher risk for developing malnutrition and experiencing its deleterious effects. Similar to other species, the body of a diseased cat responds differently to inadequate nutritional intake than does the body of a healthy cat. During periods of nutrient deprivation, a healthy animal will lose glycogen and fat primarily (simple starvation). However, sick or traumatized patients will catabolize lean body mass when they are not provided with sufficient calories (stressed starvation). During the initial stages of fasting in the healthy state, glycogen stores are used as the primary source of energy. Within days, a metabolic shift occurs towards the preferential use of stored fat deposits, sparing catabolic effects on lean muscle tissue. In diseased states, the inflammatory response triggers alterations in cytokines and hormone concentrations and shifts metabolism rapidly towards a catabolic state.2,3

There are alterations in lipid, carbohydrate, and protein metabolism that can affect the animal’s nutritional status and the outcome of the condition. The metabolic changes documented in critically ill cats include lower circulating concentration of insulin and higher concentrations of glucose, lactate, cortisol, glucagon, norepinephrine, and nonesterified fatty acids.4,5 Glycogen stores are depleted quickly, especially in strict carnivores such as cats, and this leads to an early mobilization of amino acids from muscle stores (up-regulation of proteolysis). As cats undergo continuous gluconeogenesis, the mobilization of amino acids from muscles is more pronounced than that observed in other species. Unlike other species, cats do not down-regulate gluconeogenesis or proteolysis in the face of low protein intake.6 With continued lack of food intake, energy is derived almost completely from accelerated proteolysis, which in itself is an energy-consuming process. Therefore these animals may preserve fat deposits in the face of lean muscle tissue losses. These shifts in metabolism commonly result in significant negative nitrogen and energy balance. The consequences of continued lean body mass losses include negative effects on wound healing, immune function, strength (both skeletal and respiratory), and ultimately on overall prognosis.7 The metabolic derangements that occur in critically ill cats and the deleterious effects of malnutrition make the provision of nutritional support to hospitalized cats an essential and vital part of the therapeutic approach.

INDICATIONS FOR NUTRITIONAL SUPPORT

In cats, inadequate calorie intake commonly is due to a loss of appetite (hyporexia), an inability to eat, or from persistent vomiting that accompanies many disease processes. Appetite suppression may be instigated directly by inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα) or secondarily by pathological processes (e.g., nausea, pyrexia, pain, ileus).8 Because malnutrition can occur quickly in these patients, it is important to provide nutritional support by either enteral or parenteral nutrition if oral intake is not adequate. Identification of overt malnutrition in cats can be challenging because there are no established criteria of malnutrition in companion animals. Because detectable impairment of immune function (e.g., decreased lymphocyte counts, reduced CD4+/CD8+ ratio can be demonstrated in healthy cats subjected to acute starvation by day 4, nutritional support should be considered in any ill cat with inadequate food intake for more than 3 days.9 The need to implement a nutritional intervention becomes more urgent when a cat has not eaten for more than 5 days.

There are many goals of nutritional support, but two important objectives are to treat malnutrition when it is present and to prevent malnutrition in animals at risk. Whenever possible, the enteral route should be used because it is the safest, most convenient, and most physiologically sound method of nutritional support.10 However, when patients are unable to tolerate enteral feeding (e.g., because of vomiting or diarrhea, cramping, nausea, discomfort from feeding) or unable to utilize nutrients administered enterally (e.g., because of severe inflammatory bowel syndrome, intestinal lymphoma), parenteral nutrition should be considered. Ensuring the successful nutritional management of critically ill patients involves selecting the right patient, making an appropriate nutritional assessment, and implementing a feasible nutritional plan.

NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT

As with any medical intervention, there are risks of complications when initiating nutritional interventions. Minimizing such risks depends on patient selection and patient assessment. The first step in designing a nutritional strategy is to conduct a nutritional assessment, which involves making a systematic evaluation of the patient. Nutritional assessment identifies malnourished patients who require immediate nutritional support, as well as patients who require nutritional support because they are at high risk for developing malnutrition.11

Purported indicators of overt malnutrition include recent weight loss of at least 10 per cent of body weight, poor haircoat quality, muscle wasting, signs of poor wound healing, hypoalbuminemia, lymphopenia, and coagulopathies (vitamin K deficiency).12 However, these abnormalities are not specific to malnutrition and are not present early in the process. In addition, fluid shifts may mask weight loss in critically ill patients. Factors that predispose a patient to malnutrition include anorexia lasting longer than 3 days, serious underlying disease (e.g., trauma, sepsis, peritonitis, pancreatitis, and gastrointestinal surgery), and large protein losses (e.g., resulting from protracted vomiting, diarrhea, or draining wounds).12,13 Nutritional assessment also identifies factors that can impact the nutritional plan, such as cardiovascular instability, electrolyte abnormalities, hyperglycemia, and hypertriglyceridemia, or concurrent conditions, such as renal or hepatic disease, that will impact the nutritional plan. Because a main priority of nutritional support is to avoid metabolic complications, identification of abnormalities via nutritional assessment may prompt alterations to the nutritional plan. For example, cats with uremia may not tolerate high-protein diets. Appropriate laboratory analysis should be performed in all patients to assess these parameters. Before any nutritional plan is implemented, the patient must have a stable cardiovascular system, with major electrolyte, fluid, and acid-base abnormalities corrected.

NUTRITIONAL PLAN

For each patient, the clinician should determine the appropriate route of nutrition—either enteral or parenteral. This decision should be based on the underlying disease and the patient’s clinical signs. Important factors to consider include the urgency of commencing nutritional support (e.g., cat shows overt signs of malnutrition, is at high risk of developing malnutrition, or has serious underlying disease with an expected recovery time of several weeks) and contraindications to a particular mode of nutritional support (e.g., cats with protracted vomiting will not tolerate oral or esophageal feeding, cats with oral or pharyngeal disease may benefit from gastric tube feeding). Whenever possible, the enteral route should be considered as the first choice. If enteral feedings are not tolerated or the gastrointestinal tract or parts of the gastrointestinal tract must be bypassed, parenteral nutrition should be instituted. When only a portion of the cat’s nutritional needs can be met enterally (e.g., minimal tolerance to small volumes of enteral feeding), supplemental parenteral nutrition has been demonstrated to be beneficial.14 The various alterations in metabolic pathways that occur following injury and food deprivation suggest that nutritional support should be introduced gradually and reach target levels in 48 to 72 hours.4,5

CALCULATING NUTRITIONAL REQUIREMENTS

Traditionally, the RER was multiplied by an illness factor between 1.0 to 2.0 to account for increases in metabolism associated with different conditions and injuries. Recently, there has been less emphasis on these subjective illness factors, and current recommendations are to use more conservative energy estimates to avoid overfeeding.10,12 Overfeeding can result in metabolic and gastrointestinal complications, hepatic dysfunction, increased carbon dioxide production, and weakened respiratory muscles. Of the metabolic complications, the development of hyperglycemia is most common and possibly the most detrimental. In two recent studies evaluating parenteral nutrition in cats, the application of illness factors above 1.0 was associated with higher complication rates and perhaps with higher mortality rates.15,16

Although definitive studies determining the actual nutritional requirements of critically ill cats have not been performed, general recommendations can be made. Currently, it is generally accepted that cats should be supported with 6 or more grams of protein/100 kcal (25 to 35 per cent of total energy requirements). Commercial diets formulated for recovery or recrudescence, which tend to have relatively high fat and protein contents, are typically used to meet this requirement. Patients with protein intolerance (e.g., those with hepatic encephalopathy or severe azotemia) should receive reduced amounts of protein (i.e., 4 grams protein/100 kcal).12 Similarly, patients with hyperglycemia or hyperlipidemia also may require decreased amounts of these nutrients, especially cats receiving parenteral nutrition.

Specific guidelines for instituting insulin therapy in nondiabetic cats receiving parenteral nutrition have not been published. However, administration of insulin to nondiabetic cats receiving parenteral nutrition has been reported.17 In one study evaluating the use of parenteral nutrition in cats, hyperglycemia was noted in 66 per cent of cats treated, and 75 per cent of these cats were treated with insulin.17 More recent studies have reported decreased use of insulin therapy for parenteral nutrition-related hyperglycemia, perhaps reflecting the trend of not applying illness factors in energy estimation in cats.16 In the event of cats developing hyperglycemia or hyperlipidemia, the author decreases the rate of infusion transiently by 50 per cent and reassesses response after 6 hours. If these abnormalities persist, the author reformulates the parenteral admixture to include reduced amounts of dextrose or lipids. Other nutritional requirements will depend on the patient’s underlying disease, clinical signs, and laboratory parameters.

ENTERAL NUTRITION

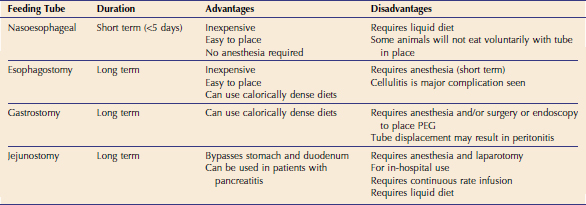

Although the enteral route should be utilized if at all possible, it is contraindicated in cats who are vomiting persistently, have severe malabsorptive conditions, or are comatose. If the enteral route is chosen for nutritional support, the next step is selecting the type of feeding tube to be used (Table 12-1). Feeding tubes used commonly in cats include nasoesophageal, esophagostomy, gastrostomy, and jejunostomy tubes. In non–surgically placed feeding tubes such as nasoesophageal or esophagostomy tubes, confirmation of correct placement via radiology or fluoroscopy is recommended. Alternatively, proper placement of these feeding tubes within the esophagus can be confirmed by use of an end-tidal carbon dioxide (CO2) monitor that detects CO2 if the tube is placed incorrectly in the trachea (Figure 12-1).

The amount of food then is calculated and a specific feeding plan devised (Box 12-1). Generally, feedings are administered every 4 to 6 hours and feeding tubes should be flushed with five to 10 mL of water after each feeding to minimize clogging of the tube. By the time of discharge, however, the number of feedings should be reduced to three to four per day to facilitate owner compliance. Commercially available veterinary liquid diets should be used for nasoesophageal and jejunostomy tube feedings due to the small bore sizes of these catheters (typically <5 Fr). Typical recovery diets usually are unsuitable for small bore tubes because of their tendency to clog these tubes. Jejunostomy tubes primarily are for in-hospital use because they require administration of a liquid diet by continuous rate infusion, and this technique also requires more vigilant monitoring. Esophagostomy and gastrostomy tubes generally are larger (>14 Fr) and allow for more calorically dense, blenderized diets to be administered. This decreases the volume of food necessary for each feeding. These tubes can be used for long-term enteral feeding. In the author’s opinion, mastering the placement of esophagostomy feeding tubes is essential in the management of critically ill animals, and this technique should be adopted in almost all practices. Placement of esophagostomy tubes requires minimal equipment, is a straightforward technique, and enables effective nutritional support. Complications associated with esophagostomy are minimal, and client compliance and satisfaction are very good. Detailed stepwise instructions are listed in Box 12-2.