Kathryn C. Gamble The order Coraciiformes includes four suborders (Alcedines, Meropes, Coracii, Bucerotes), with 10 families distributed respectively into the suborders as 3, 1, 3, and 3. It is a highly eclectic grouping of birds composed of kingfishers, todies, motmots, bee-eaters, rollers, cuckoo-rollers, ground-rollers, hoopoes, woodhoopoes, and hornbills. Birds in this order are generally diurnal (except the hook-billed kingfisher, Melidora macrorrhina) and found in the Old World (except todies, motmots, and some kingfisher species).2 They are generally nonmigratory, although some startling exceptions in the Merops bee-eaters and rollers have been documented. Each family, and often even genus, is so phenotypically distinct that it is difficult to confuse their identification with any other bird species, but they rarely ever seem to resemble other species within their own order. Extensive natural history descriptions for this order have been provided in a prior edition,4 where the topic was reviewed in its entirety, and no additions or changes have been made thereafter. Coraciiformes species generally are large headed, with short, hooked beaks and weak, short legs. Although exceptions to each of these characteristics exist, for example, the sharp beaks of the kingfishers or the delicate beaks of the hoopoes and wood hoopoes and the longer legs of the ground-rollers and ground hornbills, which move confidently by striding rather than hopping as typically seen in other species of this order. Coraciiformes species do share varying arrangements of syndactylism,2 including fusion of pedal digits 3 and 4 in kingfishers, bee-eaters, hoopoes, and woodhoopoes; fusion of pedal digits 2 and 3 in rollers; central fusion of all pedal digits in hornbills; and zygodactylous pedal digits in ground-rollers and cuckoo-rollers. Additionally, all species lack the stylohyoideus muscle, which minimizes tongue mobility and affects feeding style, and ceca,1 but all have a primitive bony stapes within the middle ear. In Bucerotes, the molting patterns of the remiges and rectrices are characteristic of the order and are extremely complex. In Momotus species, the characteristic streamers of the central pair of rectrices terminate in diamond or oval racquets, and are created as the weakly attached barbs along that plume are lost from a normally erupted feather.2 Bee-eaters present intercalated covert feathers along their primaries, whereas hornbills have no primary covert feathers. Most members of this order present brightly colored plumage, including the scarlet gorget characteristic of todies, although in hornbills spectacular keratin coloration is concentrated in the bare skin and beak rather than in the plumage. Most unusually, in the Asian hornbills in Buceros, the beak and casque coloration is based in orange and yellow carotenoid pigments as cosmetic oil obtained from the uropygial gland.2 The beak of the hornbill needs to be discussed in detail, as each of the 52 extant species develops an ornamentation on the dorsal rhinotheca (casque), which is unique to this group.2 In all but one species, the structure is an air-filled chamber created of a thin bony layer surrounded by keratin, although in some species (Tockus and Ocycerous), the casque is simply a ridge. The exception of the helmeted hornbill (Rhinoplax [Buceros] vigil) is the casque of the male that is immense and essentially solid; it is made of an “ivory,” which weighs nearly 10% of the bird’s body weight as compared with the estimated 3% to 5% in other Buceros species.2,8 The true purpose of the casque is unknown, although it has been proposed to be a resonance chamber or a hammer for nest excavation. It is presumed to be a signaling mechanism, particularly for gender and maturity, as it varies so markedly by species, gender, and age. Systematic imaging and skeletal preparation have identified relationships of this casque space within the paranasal sinus system.8 Specifically, Buceros hornbills were not found to connect the casque space to the maxillary sinus, whereas other species were demonstrated to do so. All species assessed did present a casque sinus located between the casque and the calvarium. Another unique feature of the bucerotids is the normal presence of subcutaneous emphysema. This air sac system begins to develop in the chick under the skin of the shoulders and then moves to cover the entire body by the time of fledging.2 Additional taxonomic description has been provided in a prior edition,4 and the taxonomy was reviewed in its entirety with no additions or changes for anatomy, measurements, or dietary habitats made thereafter; the exceptions have been discussed above and are listed in Table 29-1. TABLE 29-1 Supplemental Biology for the Order Coraciiformes2,4 NOTE: As Table 29-1 in the previous edition4 was well detailed and extensively reviewed, this current table only provided updates or amendments to the previously published data. No changes of any kind were needed for data on ground-rollers, cuckoo-rollers, or hoopoes. The non-hornbill species of the order overall do not tolerate extreme temperatures well. Generally, the taxon-specific approach to colder ambient temperatures is communal nocturnal roosting, especially documented in bee-eaters and woodhoopoes, and morning sunbathing.2 The exception to this cold management is found in the todies (see extensive accurate description provided in the prior edition4) and includes heterothermy, reduced basal metabolic temperature, and torpor; these adaptive mechanisms are employed most notably in females.2 These approaches are rare within other avian species, specifically heterothermy, which has been documented in two families of Passeriformes (Nectariniidae–sunbirds; Pipridae–manakins) and in Apodiformes (hummingbirds), and torpor, which has been documented in four orders—Apodiformes, Caprimulgiformes (nightjar), Coliiformes (mousebirds), Procellariiformes (petrels)—and in only one family within Passeriformes—Hirundinidae (swallows). Bee-eaters have thin plumage on their medial thighs, which allows dissipation of excess heat when the legs are lowered during flight.2 Most other taxon-specific details have not changed from the prior edition4 and exceptions are discussed later in this chapter. In the prior edition of this text, details regarding the natural habitats and reproductive parameters of this order were reviewed and have not changed thereafter.4 In spite of the several highly cooperative breeding techniques used by these species, it is important to note that many of the Coraciiformes species are highly territorial; this can complicate mixed-species displays, particularly those containing kingfishers, motmots, rollers, and wood hoopoes.2 In the prior edition of this text, details on the natural and captive diets documented were reviewed and have not changed thereafter.4 An additional detail that has to be noted is that reduced tongue mobility, as a result of lack of the retractor musculature, affects the ability of the Coraciiformes species to manipulate food. It is the beak that manipulates food items dexterously, and the manipulation ends with a head tossing technique that moves the food to the caudal oral cavity to be swallowed. The green woodhoopoe (Phoeniculus pupureus) has gender differences in beak length and size, which affects the type and size of insect prey each gender most successfully obtains. As food items are swallowed intact, nearly every species of the order has been confirmed to employ mashing or often “whacking” of food items held in the beak to soften fruits, kill prey and break its bones, or remove spines or barbs.2 This approach is particularly important for birds such as bee-eaters that consume venomous prey or when chicks are fed. Because of their consumption of whole-prey food items, many of the Coraciiformes species—even chicks—regurgitate pellets of indigestible material. This finding is particularly noteworthy in bee-eaters but rarely seen in hoopoes and never in todies. Hornbills can be categorized by their means of food carriage to the nest to feed chicks as those that carry single or multiple items, those that swallow and regurgitate the food item, and those that carry the food item intact in the beak.2 The smallest African species (Tockus) carry single food items in the bill tip, whereas the largest African species (Bucorvus) carry multiple items aligned along the beak path. The arboreal African species found in the genera Bycanistes and Ceratogymna are mainly frugivorous and similar to the Asian hornbill frugivores of the genera Anthracoceros, Aceros, and Rhyticeros, as they swallow a number of fruits and then regurgitate them singly to feed the chicks at the nest. Interestingly, the Asian species in Ocyceros that most phenotypically resemble Tockus was differentiated by its carriage of multiple ingested fruit items for regurgitation. The largest Asian hornbills of Buceros and Rhinoplax feed multiple ingested fruits to chicks by swallowing and then regurgitating the food, whereas individual prey items are carried in the beak and presented to the chicks. In the prior edition of this text, details on breeding behavior, egg appearance and number, and periods of incubation and nesting were reviewed and have not changed since4 except as follows. To the extent known, rollers are considered monogamous. Bee-eaters produce up to 8, rather than 10, eggs; hoopoes produce 4 to 8 eggs, on average; palearctic hoopoes produce up to 12 eggs; and woodhoopoes produce an average of 2 to 5 eggs.2,4 A species-specific detail to note is that each one of the 1 to 4 eggs laid by a female tody is 26% of its body mass. Each egg has a large yolk in proportion to its size because of longer incubation duration by 1 week compared with similarly sized bird’s eggs, and this imparts a rosy-sheen to the white shell. This prodigious commitment of resources is similar to that measured in only two other avian families, Apterygidae (kiwi) and Hydrobatidae (storm petrel), whereas in most other avian species, a given egg makes up between 1.8% to 11% of the female’s body weight.2 Coraciiformes neonates are hatched altricial, with prognathism that is maintained for several days. As the order members are cavity-nesters, often with minimal nest material, the chicks have prominent tarsal callosities to cushion this area. They are all gymnopedic, except for the montane blue-throated motmot (Aspatha gularis), cuckoo-roller, hoopoe, and green woodhoopoe. However, all Coraciiformes species have quill-like eruptions of their developing feathers, which persist in the waxy sheaths for a protracted time. As the majority of the order is naked of other plumage at this stage, the chick has a startling appearance that has been described as resembling a “hedgehog,” a “pincushion,” or a “porcupine.” The chicks essentially fledge with a duller version of the adult plumage. Some species-specific information with regard to the cavity nesting of Coraciiformes is presented in Table 29-2. These factors affect housing, nesting provision, and chick rearing potential. The asynchronous hatching of the laughing kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguinaea) is particularly noteworthy, as siblicide of the younger chicks is frequent when resources are limited.2 This species, by an unknown mechanism, also manipulates the gender of its chicks with the first eggs nearly always being male and second eggs being nearly always female. With the gender disparity of females of larger size than males in the Alcedines, this arrangement provides a catching-up potential for the second chick while permitting the first chick to establish itself. A second species-specific occurrence would be one egg from each green woodhoopoe clutch often failing to hatch, which appears to be a population-adaptive mechanism in wild populations.2 Finally, as with adults, tody chicks are particularly vulnerable to cold temperatures. They are documented to huddle closely within the nest for warmth in a more taxon-typical manner to thermoregulation as compared with the adults of this species.2 TABLE 29-2 Nesting Characteristics of the Order Coraciiformes2

Coraciiformes (Kingfishers, Motmots, Bee-Eaters, Hoopoes, Hornbills)

Taxonomy and Biology

Unique Anatomy

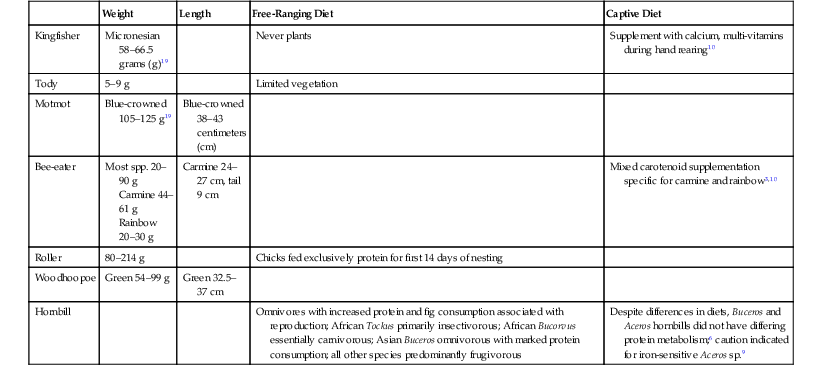

Weight

Length

Free-Ranging Diet

Captive Diet

Kingfisher

Micronesian 58–66.5 grams (g)19

Never plants

Supplement with calcium, multi-vitamins during hand rearing10

Tody

5–9 g

Limited vegetation

Motmot

Blue-crowned 105–125 g19

Blue-crowned 38–43 centimeters (cm)

Bee-eater

Most spp. 20–90 g

Carmine 44–61 g

Rainbow 20–30 g

Carmine 24–27 cm, tail 9 cm

Mixed carotenoid supplementation specific for carmine and rainbow3,10

Roller

80–214 g

Chicks fed exclusively protein for first 14 days of nesting

Woodhoopoe

Green 54–99 g

Green 32.5–37 cm

Hornbill

Omnivores with increased protein and fig consumption associated with reproduction; African Tockus primarily insectivorous; African Bucorvus essentially carnivorous; Asian Buceros omnivorous with marked protein consumption; all other species predominantly frugivorous

Despite differences in diets, Buceros and Aceros hornbills did not have differing protein metabolism;6 caution indicated for iron-sensitive Aceros sp.9

Special Physiology

Housing Requirements

Feeding

Reproduction and Neonatal Care

Location

Appearance

Annual Replacement

Hatching Synchronicity

Kingfisher

Mud bank (most); tree; termite mound

Excavated or preformed chambers

Reused

Synchronous, except pied kingfisher (Ceryle rudis) and laughing kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae)

Tody

Earth embankment

Excavated burrows or tunnels

Replaced

Unknown

Motmot

Earth embankment

Excavated burrows

Replaced

Synchronous, except turquoise-browed motmot (Eumomota superciliosa)

Bee-eater

Earth embankment

Excavated holes

Replaced

Asynchronous

Roller

Tree (nearly all); earth

Excavated or enlarged holes

Unknown

Asynchronous

Ground-roller

Ground or earth embankment; except tree short-legged roller (Brachypteracias leptosomus)

Excavated burrows

Unknown

Unknown

Cuckoo-roller

Tree

Preformed cavity

Unknown

Unknown

Hoopoe

Rock; tree (secondary)

Preformed cavity

Reused but annual change to pair using

Asynchronous

Woodhoopoe

Tree

Preformed cavity

Unknown

Variable synchronicity

Ground hornbill

Flat ground

Minimal excavation

Variable, generally area reused

Synchronous

Hornbill

Tree

Excavated or enlarged cavities

Variable, generally reused

Asynchronous ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Coraciiformes (Kingfishers, Motmots, Bee-Eaters, Hoopoes, Hornbills)

Chapter 29