Chapter 3 Conservation Medicine for Zoo Veterinarians

The new scientific discipline of conservation medicine is rapidly gaining acceptance as a framework that encompasses the complexity of disease ecology and its application to wildlife species conservation. As such, there is a burgeoning body of literature and resources available and, although it is outside the scope of this chapter to provide a comprehensive review, we have included references to some key resources for those who wish to pursue the topic in greater detail. Additional complementary information may be found in Chapters 1 and 21. As indicated by Deem,8 we believe that zoo veterinarians have unique skills and expertise to offer conservation medicine programs in their local communities as well as nationally and internationally. Our aim in this chapter is to inform and encourage zoo veterinarians throughout the world to become actively engaged in conservation medicine projects.

Historical Considerations

Conservation Medicine: A Shift in Focus

The discipline of conservation medicine emerged in the 1990s in North America in response to increasing concerns about the adverse effects of anthropogenic environmental change on human, animal, and ecosystem health. A need to broaden our approach to understand the complex interaction of parameters influencing health became increasingly evident at this time.*

The underpinning paradigm that emerged is that the health of all living organisms (including Homo sapiens) is a manifestation of the health of the environment of which they are an integral part and that there is a constant interplay between variables impacting environmental, animal and human health. Deem and colleagues have described conservation medicine as “the application of medicine to augment the conservation of wildlife and ecosystems.”9 This perspective provides a broader context for the investigation of, and response to, health issues—breaking down artificial boundaries between the health and environmental sciences and extending the preventive approach practiced by zoo veterinarians to a wider application beyond the zoo gates (Fig. 3-1).

The Manhattan Principles

In 2004, the Wildlife Conservation Society hosted an international symposium under the banner of “One World, One Health” in New York, with the aim of building “interdisciplinary bridges to health in a globalized world.” The 12 recommendations arising from this event are known as the Manhattan Principles. These urged governments, health institutions, and global organizations to recognize the need for a holistic approach to health issues, an approach that recognizes the health continuum among people, animals, and the ecosystems that support biodiversity on this planet.3 Over the last decade, a growing number of professional veterinary, medical, and environmental health organizations have formally declared their support for this approach. These include the World Animal Health Organisation (OIE), World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), American Medical Association (AMA), and World Association of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosticians (WAVLD). See the One Health Initiative website (http://www.onehealthinitiative.com/index.php).

Zoo Veterinary Practice and Conservation Medicine

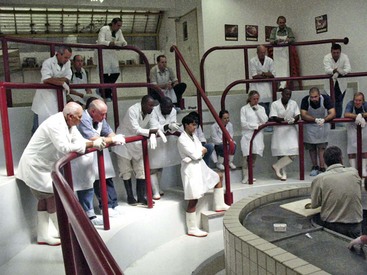

In comparison to the single-species focus of human medicine, the undergraduate training of veterinarians provides a broad education in comparative medicine and surgery. Nowhere is this comparative approach more applied and extended than in zoological medicine (Fig. 3-2).

Standard practice for zoo veterinarians is to adopt a holistic preventive approach that includes consideration of the social and environmental influences on animal health and the potential for cross-species and zoonotic disease transmission. This necessarily entails close collaboration with a diverse range of stakeholders, including animal care staff, a range of veterinary and human medical specialists, special interest groups (e.g., wildlife rehabilitators, community conservation and animal welfare groups), and regulatory agencies. For field-based programs, additional collaborative partnerships with a range of individuals and organizations are essential for the zoo veterinarian to perform effectively and add value to any project.8 The collaborative, transdisciplinary, ecosystem-based approach of conservation medicine should not, therefore, represent a major shift in perspective for experienced zoo veterinarians.

The World Association of Zoos and Aquaria Conservation Strategy, in calling for greater integration between zoo (ex situ) and field (in situ) conservation projects, specifically recognizes the important contribution made by zoo veterinarians to the success of these endeavors through their clinical, diagnostic, and scientific research activities.34 As Osofsky and colleagues have stated, “critical clinical problems mandate a rigorous diagnostic plan, a multi-faceted therapeutic plan, clear communication and short- and long-term monitoring. Critical conservation problems deserve no less.”26

Zoo veterinarians may also bring considerable expertise to the planning and implementation stages of wildlife conservation projects. As such, it is important for conservation managers to move beyond the common misconception that the main contribution that zoo veterinarians may make to an in situ wildlife conservation project is the chemical immobilization of study animals to enable research.10 Examples of the many areas to which zoo veterinarians may contribute expertise to conservation programs is presented in Box 3-1.

BOX 3-1 Data from References 8, 10-12, 22, 29, and 30.

Some Areas of Zoo Veterinary Involvement in Conservation Medicine Programs

Zoo Veterinarians in Biodiversity Hotspots

Mittermeier and associates23 have identified 34 biodiversity hotspots that, in total, cover only 2.3% of the earth’s surface. Endemic to these regions are 50% of plant species, 42% of terrestrial vertebrates, and 29% of freshwater fish. By definition, a hotspot region must contain at least 1500 endemic plant species and have lost 70% of its original habitat.23 Although New Zealand and southwest Australia are included as hotspot regions, most biodiversity hotspots are located in developing countries. Many conservationists argue that global biodiversity conservation outcomes may be maximized by concentrating conservation efforts and limited resources in these biodiversity hotspot regions.23,24

Zoo veterinarians in developing countries, therefore, have a particularly important role to play in biodiversity and endangered species conservation programs. In developing countries, in particular, effective long-term environmental conservation may usually only be achieved by working with local communities to conserve endangered species, protect habitats, and promote sustainable development. Increasingly, human-wildlife conflicts in these countries are intensifying, associated with the proximity of rural farming communities to wildlife populations living in diminishing remnant habitats. Innovative wildlife conservation policies and practices are needed to address these conflicts if there is to be any possibility of ensuring environmentally sustainable development for rural communities along with biodiversity conservation. Zoo veterinarians in developing countries are in the best position to apply their knowledge and skills to specific wildlife conservation dilemmas faced by their countries. Zoo veterinarians elsewhere may build collaborative links with their colleagues in developing countries and assist with capacity building and resource support (see later). In doing so, it is important that they channel resources into projects that address local conservation priorities rather than projects based on personal interest or institutional bias.25 Kock and Kock19 have discussed conservation initiatives in developing countries and outlined the need for adaptive action that encourages home-grown solutions to problems. They warn against transfer of technology and practices from developed countries that may be inappropriate, impractical, and unsustainable within the context of the country’s resources and capabilities.

Conservation Medicine in Practice

Establishing a Conservation Medicine Infrastructure in New Zealand

Activities

In 1990, the Auckland Zoo embarked on a mission to develop close collaborative relationships with key stakeholders involved in native species conservation. A significant contributor has been research and training by its veterinarians to conduct disease surveillance and establish baseline health profiles for threatened native species (Fig. 3-3).15 Training of DOC staff, university researchers, and others in diagnostic sample collection and field necropsy methodology has been a key strategy. In 1999, zoo veterinarians, commissioned by the DOC, developed a disease risk assessment tool for wildlife translocations.16 This was further refined in collaboration with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (CBSG)1,21 and is now standard operating procedure for all wildlife translocations within New Zealand.4 To raise awareness of conservation medicine, Auckland Zoo and Unitec New Zealand hosted a national symposium in 2005, drawing participants from human, animal, and environmental sectors in Australasia.14 At the same time, a public fundraising campaign culminated in the establishment of the zoo’s clinical, research, and teaching facility, the New Zealand Centre for Conservation Medicine (NZCCM), opened by the Prime Minister in August 2007. A key objective of this center is to provide a hub to facilitate collaborative networks in support of wildlife health teaching and research for biodiversity conservation. In 2009, a national wildlife health database to collate and disseminate wildlife health and surveillance data was launched by DOC and is managed, on contract, by the Auckland Zoo. Further information may be found at http://www.conservationmedicine.co.nz.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree